Neil Shubin stands as one of the most influential paleontologists of the modern era, whose groundbreaking discovery of Tiktaalik roseae fundamentally changed our understanding of vertebrate evolution. His work illuminated the critical transition between aquatic and terrestrial life, bridging a gap in evolutionary science that had persisted for decades. Shubin’s interdisciplinary approach, combining paleontology, developmental biology, and genetics, has reshaped how we conceptualize evolutionary transitions and the development of key anatomical features. Through his research, writing, and teaching, he has not only advanced scientific knowledge but also made complex evolutionary concepts accessible to the general public, demonstrating the power of fossil evidence in telling the story of life’s greatest adaptational leaps.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Neil Shubin was born on December 22, 1960, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where his early fascination with natural history would eventually blossom into a distinguished scientific career. As the son of a University of Pennsylvania medical school administrator, Shubin grew up in an environment that valued education and intellectual curiosity. He completed his undergraduate studies at Columbia University, where he initially planned to follow a pre-medical track before becoming captivated by paleontology and evolutionary biology. This pivot led him to pursue graduate studies at Harvard University, where he earned his Ph.D. in organismic and evolutionary biology in 1987. His doctoral research, focusing on the evolution of early tetrapods, established the foundation for what would become his life’s most significant work – understanding the transition of vertebrates from water to land. These formative academic experiences shaped Shubin’s interdisciplinary approach, combining fieldwork, comparative anatomy, and developmental biology in ways that would later revolutionize our understanding of evolutionary transitions.

The Hunt for Tiktaalik

Shubin’s most celebrated scientific achievement began as a carefully calculated expedition based on evolutionary theory and geological knowledge. In the late 1990s, Shubin and his colleagues Ted Daeschler and Farish Jenkins Jr. reasoned that if they wanted to find fossils documenting the water-to-land transition, they needed rocks of the right age (approximately 375 million years old) and the right type (ancient stream deposits). This logical approach led them to Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic, one of the few accessible places on Earth with exposed rock formations matching their criteria. The team endured harsh Arctic conditions across multiple field seasons, beginning in 1999 and persisting through disappointments and logistical challenges. Their persistence was rewarded in 2004 when they discovered several specimens of what would be named Tiktaalik roseae, a creature that perfectly represented the transition between fish and tetrapods. The name “Tiktaalik” came from local Inuit elders, meaning “large freshwater fish,” honoring the indigenous knowledge of the region where this scientific treasure was unearthed. This discovery was not just luck but the result of Shubin’s methodical application of evolutionary theory to predict where transitional fossils might be found.

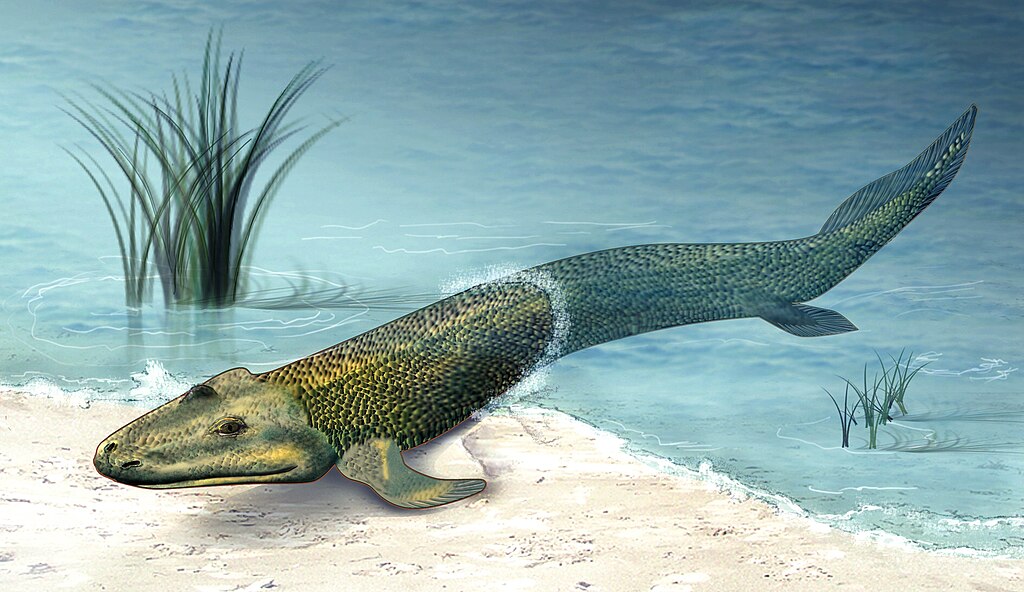

Tiktaalik: The Remarkable Transitional Fossil

Tiktaalik roseae represents one of the most significant transitional fossils ever discovered, providing critical evidence of evolutionary change between fish and the first four-limbed animals. Dating to approximately 375 million years ago during the Late Devonian period, this remarkable creature exhibited characteristics of both fish and tetrapods in a single organism. Tiktaalik possessed scales and gills like a fish, yet also featured a flattened head similar to a crocodile, with eyes positioned on top rather than on the sides – an adaptation suited for looking up while mostly submerged. Most significantly, Tiktaalik had robust fins with internal skeletal structures that contained primitive wrist bones and fingers, allowing it to prop itself up and possibly move in shallow water or on land for short periods. The creature’s ribs were more developed than those of fish, providing support for its body outside of water, while its neck could move independently of its shoulders – a crucial innovation not found in fish. These features collectively demonstrate how evolution works through a series of incremental adaptations rather than sudden leaps, making Tiktaalik what Shubin calls a “fishapod” – neither fully fish nor fully tetrapod, but a perfect representation of evolutionary transition.

Scientific Impact and Evolutionary Significance

The discovery of Tiktaalik profoundly impacted evolutionary biology by providing tangible evidence for a major transition in vertebrate evolution that had previously been theoretical. This fossil effectively closed a significant gap in the fossil record between fish like Panderichthys, which lived about 385 million years ago, and early tetrapods like Acanthostega from about 365 million years ago. Shubin’s work demonstrated that the development of tetrapod features occurred gradually and in a predictable sequence, rather than as a sudden evolutionary leap. The scientific community recognized the significance of this discovery almost immediately, with the research being published in the prestigious journal Nature in 2006 and garnering widespread attention across scientific disciplines. Tiktaalik became a powerful counter to arguments against evolutionary theory that cited “missing links” in the fossil record. Beyond its importance for understanding tetrapod origins, Shubin’s discovery reinforced the methodology of combining evolutionary theory with geological knowledge to make testable predictions about where transitional fossils might be found. This approach has since influenced paleontological expeditions worldwide, encouraging researchers to strategically target locations based on evolutionary hypotheses rather than relying solely on chance discoveries.

From Fins to Limbs: Developmental Insights

Shubin’s research extends beyond fossil hunting to encompass developmental biology, where he has made significant contributions to understanding the genetic basis of evolutionary transitions. His laboratory work has revealed how the same genetic mechanisms that build fins in fish have been repurposed through evolution to create limbs in tetrapods. Particularly important is his research on Hox genes, which control body patterning during embryonic development across diverse animal species. Shubin and colleagues demonstrated that the expression patterns of these genes in developing fish fins share fundamental similarities with the patterns seen in developing tetrapod limbs. Through careful comparative studies of gene expression in modern organisms like zebrafish, mice, and other vertebrates, Shubin’s team has traced the molecular pathways that were modified during the fin-to-limb transition. This work revealed that the basic genetic toolkit for building limbs was already present in fish ancestors, and evolutionary changes primarily involved modifications to when and where these genes were activated rather than the invention of entirely new genes. These developmental insights complement the fossil evidence from Tiktaalik, providing a comprehensive picture of how evolutionary innovations arise through both genetic and anatomical modifications over time.

Academic Career and Research Leadership

Neil Shubin has built an illustrious academic career spanning multiple prestigious institutions, establishing himself as a leader in evolutionary biology research. After completing his education, he served as a faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania and later at the University of Chicago, where he currently holds the position of Robert R. Bensley Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy. His laboratory at the University of Chicago has become an international hub for research on vertebrate evolution, attracting talented graduate students and postdoctoral researchers from around the world. Shubin also maintains an association with the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, where he has served as Associate Dean for Academic Strategy and as Provost. His leadership extends beyond individual institutions to the broader scientific community, where he has served on numerous advisory boards and committees for organizations like the National Science Foundation and the National Academy of Sciences. Throughout his career, Shubin has championed interdisciplinary approaches to evolutionary research, integrating paleontology, comparative anatomy, developmental biology, and genetics to address fundamental questions about major transitions in vertebrate evolution. His collaborative research style has fostered connections between scientists across traditionally separate fields, helping to create a more integrated understanding of evolutionary processes at multiple scales.

Science Communication and Public Education

Shubin has distinguished himself not only as a researcher but also as an exceptional science communicator who makes complex evolutionary concepts accessible to the general public. His 2008 book “Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body” became an international bestseller, translating his scientific discoveries into engaging narrative form. This book explores how the human body bears the imprints of our evolutionary history, tracing various anatomical features back to their origins in ancient ancestors. The book’s success led to a three-part PBS television series of the same name in 2014, which Shubin hosted, further expanding the reach of his evolutionary insights. Beyond these major projects, he regularly contributes to public understanding of science through articles, interviews, and public lectures that demystify paleontology and evolutionary biology. Shubin’s teaching has also made a significant impact, particularly through his involvement in developing and teaching the core biology curriculum at the University of Chicago, where he helps undergraduates grasp fundamental evolutionary concepts. His talent for communication stems partly from his ability to connect abstract scientific concepts to tangible, relevant examples that resonate with diverse audiences, making him an effective ambassador for evolutionary science in the public sphere.

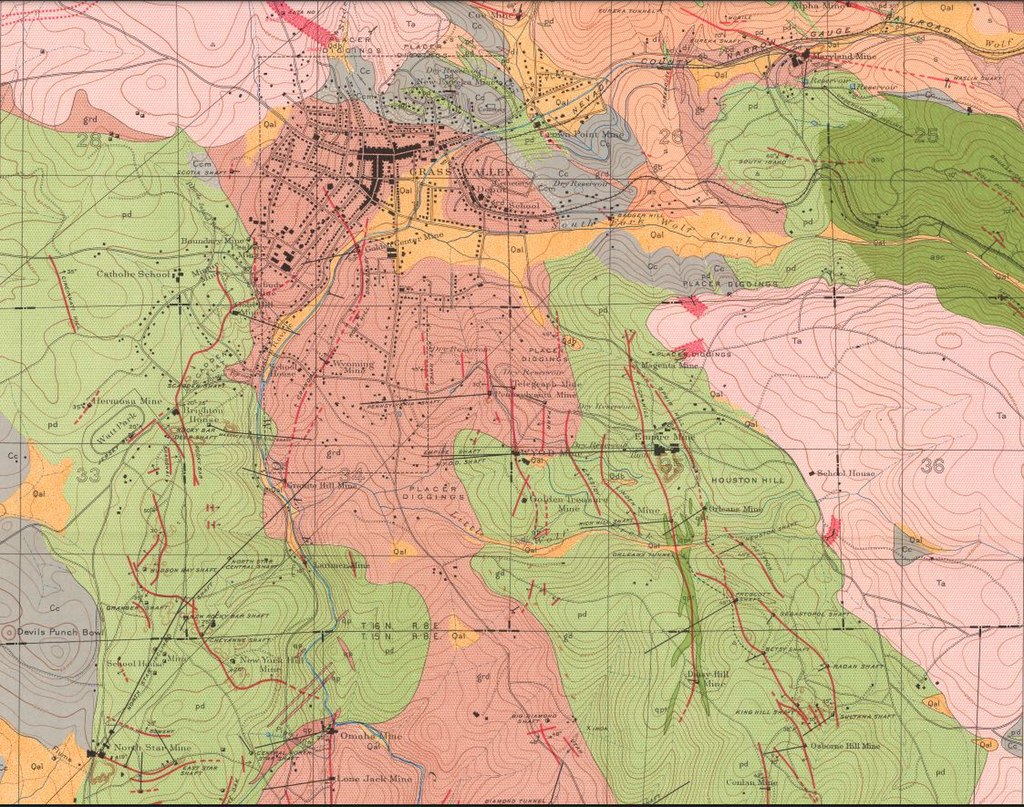

Fieldwork Methodology and Exploration Techniques

Shubin’s approach to paleontological fieldwork represents a methodological advance that combines theoretical prediction with practical exploration techniques. Rather than relying on chance discoveries, Shubin pioneered what colleagues call “hypothesis-driven fieldwork,” where expeditions are planned based on evolutionary and geological predictions about where specific transitional fossils should be found. This approach requires extensive preliminary research to identify rock formations of the appropriate age and depositional environment before launching costly expeditions. In the Arctic expeditions that led to Tiktaalik, Shubin’s team used satellite imagery, geological maps, and previously published research to identify promising locations before ever setting foot in the field. Once on site, they employed systematic survey methods, carefully documenting the stratigraphic context of all discoveries to place them accurately in evolutionary time. Shubin’s field techniques also include innovative approaches to fossil extraction and preservation in challenging environments, such as the quick-setting resins and specialized tools developed for recovering delicate specimens from the Arctic permafrost. His field journals, which meticulously record not just fossil findings but also environmental conditions, team dynamics, and methodological adjustments, have become resources for other paleontologists planning expeditions to remote locations. Through these methodological innovations, Shubin has helped transform paleontology from a discipline sometimes characterized as fossil collecting into a hypothesis-testing science that actively investigates evolutionary transitions.

Beyond Tiktaalik: Other Research Contributions

While Tiktaalik remains Shubin’s most celebrated discovery, his research portfolio extends far beyond this single fossil, encompassing diverse aspects of vertebrate evolution and development. His work on limb development has included significant studies on digit formation across various vertebrate groups, revealing evolutionary patterns in how fingers and toes develop. Shubin has also conducted important research on the evolution of sensory systems, particularly investigating how the neural pathways for smell, vision, and hearing have evolved across the fish-tetrapod transition. His comparative anatomical studies have extended to the evolution of feeding mechanisms, examining how jaw structures transformed as vertebrates adapted to different environments and food sources. In collaboration with geneticists, Shubin has investigated the molecular basis for evolutionary novelty, helping to identify how genetic changes drive major anatomical innovations. His research has also addressed broader patterns in vertebrate evolution, including studies on the Permian-Triassic extinction event and subsequent vertebrate radiations that shaped the modern fauna. Through these diverse research directions, Shubin has consistently contributed to a deeper understanding of how major evolutionary transitions occur, focusing not just on the dramatic shifts but also on the incremental changes that accumulate to produce evolutionary innovations across various body systems.

Philosophical Contributions to Evolutionary Theory

Beyond his empirical research, Shubin has made notable contributions to the philosophical underpinnings of evolutionary theory, particularly regarding how we conceptualize evolutionary transitions. Through his writings and lectures, he has helped refine the concept of “transitional forms,” arguing against the common misconception that these represent imperfect intermediate steps in a linear progression. Instead, Shubin emphasizes that organisms like Tiktaalik were fully functional, well-adapted creatures in their own right, not merely “works in progress” toward some predetermined evolutionary outcome. This perspective challenges teleological thinking in evolution and reinforces the understanding that natural selection operates on immediate functionality rather than future potential. Shubin has also contributed to discussions about the relationship between microevolutionary processes (observable in laboratory settings) and macroevolutionary patterns (visible in the fossil record), suggesting mechanisms through which small genetic changes can accumulate to produce major morphological innovations over geological time. His work highlights the importance of developmental constraints in channeling evolutionary possibilities, demonstrating how the shared genetic architecture of vertebrates both enables and limits evolutionary change. Through these philosophical contributions, Shubin has helped bridge conceptual divides between paleontology and molecular biology, fostering a more integrated understanding of evolution across different timescales and levels of biological organization.

Awards and Recognition

Shubin’s groundbreaking contributions to evolutionary biology and paleontology have earned him numerous prestigious accolades throughout his career. In 2009, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, one of the highest honors an American scientist can receive, recognizing his exceptional contributions to scientific research. The Miller Institute for Basic Research in Science awarded him the Miller Research Professorship, providing him with the opportunity to pursue innovative research directions. For his exceptional ability to communicate science to the public, Shubin received the National Academy of Sciences Koshland Award for Public Engagement with Science in 2013, acknowledging his effectiveness in translating complex evolutionary concepts for general audiences. His book “Your Inner Fish” was recognized with the Phi Beta Kappa Science Book Award and was named a National Academies Communication Award finalist. The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has honored him with the Romer-Simpson Medal, their highest award recognizing sustained and outstanding scholarly excellence in the field of vertebrate paleontology. Universities around the world have recognized Shubin’s contributions through honorary doctorates, including from his undergraduate alma mater, Columbia University. These recognitions collectively affirm Shubin’s status as not only a pioneering researcher but also an exceptional educator and communicator who has significantly advanced both scientific knowledge and public understanding of evolution.

Influence on Modern Evolutionary Science

Neil Shubin’s work has profoundly influenced modern evolutionary science, creating ripple effects across multiple disciplines and reshaping research agendas. His integrative approach to studying evolutionary transitions has inspired a generation of scientists to bridge traditional boundaries between paleontology, developmental biology, and genetics. The “evo-devo” field (evolutionary developmental biology) has particularly benefited from Shubin’s work, as researchers increasingly investigate how developmental mechanisms have been modified through evolution to generate morphological diversity. His success in predicting and discovering Tiktaalik has validated hypothesis-driven approaches to paleontological fieldwork, encouraging more strategic expeditions targeting specific evolutionary questions rather than opportunistic fossil collection. Shubin’s emphasis on studying major transitions in vertebrate evolution has also influenced funding priorities, with agencies like the National Science Foundation increasingly supporting projects focused on evolutionary innovations and adaptive radiations. In educational contexts, his accessible explanations of complex evolutionary processes have transformed how evolution is taught in university curricula, emphasizing the continuum of change rather than discrete “missing links.” Perhaps most significantly, Shubin’s work has helped counter anti-evolution arguments by providing tangible evidence for major evolutionary transitions and demonstrating how modern scientific methods can test and validate evolutionary theory. Through these various channels of influence, Shubin has helped shape evolutionary science into a more integrated, predictive, and publicly accessible field.

Legacy and Ongoing Research

As Neil Shubin continues his active research career, his scientific legacy continues to grow through both his direct contributions and the work of students and colleagues he has mentored. His laboratory at the University of Chicago remains at the forefront of research on vertebrate evolution, currently exploring new directions in understanding how genetic regulation influences evolutionary change across major transitions. Ongoing projects include detailed investigations of the genetic basis for skull evolution and further explorations of limb development across diverse vertebrate lineages. Shubin continues to lead field expeditions, with recent work in China, Greenland, and other locations searching for additional transitional fossils that might illuminate other key evolutionary transitions. His mentorship has produced dozens of leading scientists who now direct their own research programs around the world, extending his influence through an academic family tree that spans multiple institutions. The methodological approaches Shubin pioneered – integrating fossil evidence with developmental and genetic data – have become standard practice in evolutionary biology, ensuring his impact will continue well beyond his personal research contributions. Through his continuing public engagement efforts, including new books, lectures, and media appearances, Shubin also extends his legacy as a champion of scientific literacy and evolutionary understanding.