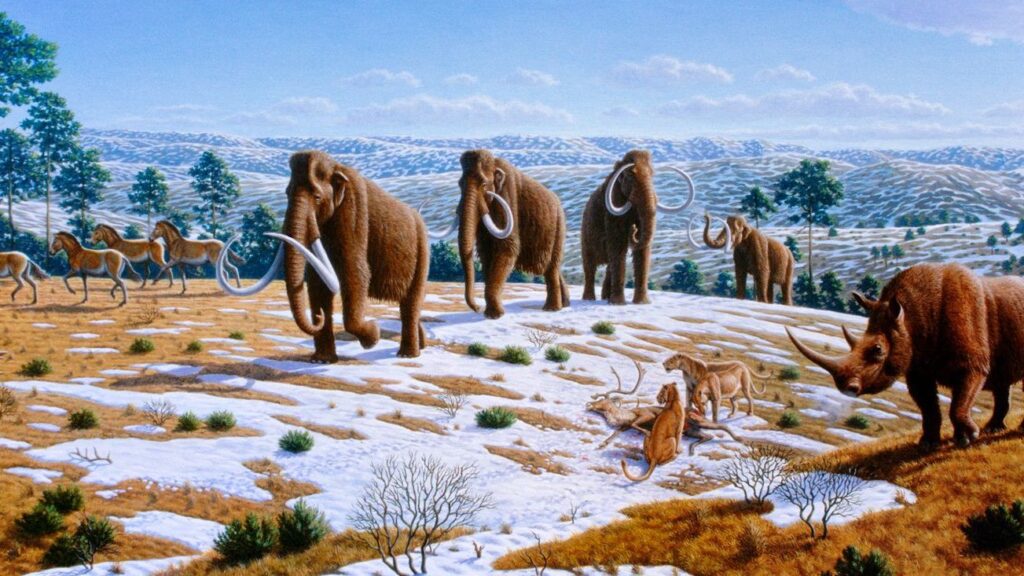

When you think about prehistoric giants, you probably imagine lumbering beasts driven solely by instinct. Massive creatures that roamed ancient landscapes with little more than hunger and fear guiding their actions. Here’s the thing though. Recent discoveries are forcing scientists to reconsider everything they thought they knew about the cognitive abilities of Ice Age megafauna.

Were woolly mammoths, giant ground sloths, and other colossal creatures actually far smarter than we’ve given them credit for? The evidence is starting to pile up, and honestly, some of it is pretty mind-blowing. Let’s get started and explore what science is revealing about these extraordinary animals.

Brain Size Doesn’t Tell the Whole Story

You’ve probably heard that bigger brains equal smarter animals. Simple, right? Not exactly. Compared to their modern elephant relatives, mammoths had relatively larger brains, hinting at a higher capacity for information processing and problem-solving. The brain of the woolly mammoth specimen examined, estimated to weigh between 4,230 and 4,340 grams, showed the typical shape, size, and gross structures observed in extant elephants.

What really gets interesting is when you look beyond mere size. As the Elephantidae brain structure seems to be evolutionarily conservative, it can be assumed that the woolly mammoth could have achieved the same cognitive capacities as the extant elephants. Elephants are known for their extensive long-term memory, problem-solving abilities, behavioural adaptability, their ability to recognize themselves in a mirror, to manipulate their environment, and to manufacture tools with their trunk. If mammoths possessed similar mental capabilities, we’re talking about animals capable of complex thought, social cooperation, and perhaps even emotional depth.

The Elephant in the Ice Age Room

Let’s be real, modern elephants are incredibly intelligent. They grieve their dead, they remember locations and individuals for decades, they cooperate to solve problems. There’s no reason to think their extinct relatives were any different. The similarity to the morphology of the African elephant suggests that the woolly mammoth had comparable communication skills, social behavior and intelligence.

Think about what this means. Mammoths lived in harsh Ice Age environments where temperatures plummeted and resources were scarce. Survival required more than brute strength. These animals likely needed advanced spatial memory to recall where food sources appeared seasonally, sophisticated communication to coordinate herd movements, and the cognitive flexibility to adapt their behavior to changing conditions. Like elephants, mammoths were highly social animals, which would have required advanced communication and cooperation skills, further suggesting a sophisticated intelligence.

Giant Ground Sloths Were Not Slow Thinkers

When you picture a sloth, you probably think of those adorable but sluggish tree-dwellers hanging upside down in the rainforest. Their extinct cousins were wildly different. Megatherium americanum is one of the largest known ground sloths, with a total body length of around 6 metres. These elephant-sized herbivores weren’t climbing trees. They were standing upright, reaching high branches, and possibly even digging burrows.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that these sloths may have congregated and died in a mass mortality event in a marshy riparian habitat, including a multigenerational age structure with adult and large juvenile individuals well-represented. This tells us something crucial. These animals lived in social groups with complex intergenerational structures. The ground sloths exhibit similar changes in ontogeny to those observed in modern sloths, indicating that ground sloth juveniles may have engaged in similar behaviors to those of modern sloths, such as clinging to their mothers for transportation, and ground sloth juveniles also possess morphological traits that have been linked with semiarboreal behaviors.

The cognitive demands of social living shouldn’t be underestimated. Honestly, managing relationships within a group requires memory, emotional regulation, and the ability to predict others’ behavior.

Environmental Mastery Required Brains, Not Just Brawn

Survival during the Late Pleistocene wasn’t for the intellectually faint of heart. Researchers have examined the mass extinction of large animals over the past tens of thousands of years and found that extinct species had, on average, much smaller brains than species that survived, and the researchers link the size of the brain in relation to the body size of each species to intelligence, concluding that a large brain indicates relatively high intelligence, which helped the extant species adapt to changing conditions and cope with human activities such as hunting.

Consider what this means for species that survived. Modern elephants, rhinos, and hippos all have proportionally larger brains relative to their body size. They’re behaviorally flexible, capable of learning new survival strategies, and can modify their behavior based on environmental threats. The megafauna that went extinct may have lacked this critical cognitive edge. Brain size and body mass co-evolved in proboscideans across the Cenozoic; however, this pattern appears disrupted by two instances of specific increases in relative brain size in the late Oligocene and early Miocene.

It’s hard to say for sure, but the evidence suggests that intelligence wasn’t just a nice bonus for Ice Age megafauna. It might have been essential for survival.

Problem Solving Was Essential for Megafaunal Survival

You ever wonder how a five-ton animal finds enough food every day in a frozen landscape? The answer probably involved considerable cognitive ability. Evidence shows Paramylodon harlani specialized in hard foods such as roots, tubers, or fungi, and its powerful forelimbs and claws would have aided this behavior, making it a crucial forager of underground resources. This wasn’t random digging. It required the animal to remember where productive foraging sites were located, to recognize seasonal patterns in resource availability, and potentially to use problem-solving skills to access buried food.

Nothrotheriops shastensis was a selective browser, feeding on desert plants like yucca, agave, pine, and saltbush and shaping shrubland habitats in the process. Selective feeding demonstrates discrimination. These animals weren’t mindlessly eating everything in their path. They were making choices based on nutritional content, digestibility, and perhaps even taste preferences. That requires a level of cognitive assessment we rarely consider in extinct species.

Social Intelligence May Have Been Their Greatest Asset

Living in groups is complicated. It demands sophisticated cognitive abilities that solitary animals simply don’t need. The social brain hypothesis was proposed by British anthropologist Robin Dunbar, who argues that human intelligence did not evolve primarily as a means to solve ecological problems, but rather as a means of surviving and reproducing in large and complex social groups, and some of the behaviors associated with living in large groups include reciprocal altruism, deception, and coalition formation.

While this hypothesis was developed to explain human intelligence, it applies equally well to other social species. Elephants today live in matriarchal herds where older females lead based on accumulated knowledge and experience. There’s no reason to think mammoths functioned differently. Researchers suggest mammoths might have had complicated behavior, similar to modern elephants. The cognitive demands of tracking relationships, remembering past interactions, coordinating group movements, and teaching younger generations would have favored the evolution of larger, more sophisticated brains.

Let’s be honest. Managing social relationships is exhausting even for humans. Imagine doing it without language but with stakes that include survival in one of Earth’s harshest climates.

What We’ve Lost in Understanding These Ancient Minds

The extinction of megafauna represents more than just the loss of impressive physical specimens. Giant ground sloths were neither analogous to living sloths nor ecological replicates of other herbivores at the La Brea Tar Pits, they played unique and complementary roles, and when they disappeared, entire ecological functions were lost. We lost behavioral diversity, cognitive strategies refined over millions of years, and perhaps forms of intelligence we can barely imagine.

The high position of megafauna among the hunting prey of humans in South America reinforces their central role in extinctions. These animals didn’t just disappear because of climate change. Human hunting pressure likely played a significant role. The irony is devastating. We may have eliminated some of the most cognitively sophisticated animals that ever walked the Earth, and we’ll never fully understand what we lost.

Conclusion: Rethinking Prehistoric Intelligence

Science continues to reveal that ancient megafauna were far more cognitively complex than early researchers imagined. From the sophisticated social structures of mammoth herds to the selective foraging strategies of giant ground sloths, these animals demonstrated intelligence that deserves our respect and recognition. Their brain structures, their behaviors, and their survival strategies all point toward mental capabilities that we’re only beginning to appreciate.

Maybe it’s time we stopped thinking of Ice Age animals as primitive brutes and started recognizing them as the intelligent, behaviorally flexible beings they likely were. The evidence is there if we’re willing to look at it with fresh eyes. What other surprises might these ancient giants still have waiting for us to discover?