Picture yourself standing in what would one day become North Dakota, surrounded by towering sequoias and lush tropical foliage that wouldn’t look out of place in modern Indonesia. Now fast forward a few million years, and you’d find yourself in a windswept grassland with herds of prehistoric horses thundering past.

The prehistoric United States was nothing like the country you know today. From steaming swamps to frozen tundra, the plants and animals that called this place home had to adapt or disappear. Some developed incredible survival mechanisms that allowed them to thrive for millions of years. Their stories reveal nature’s genius at its finest, showing you just how creative evolution can be when the stakes are literally life or death.

Mastodons and Their Cold Weather Armor

Mastodons were homegrown elephants that evolved in North America roughly three and a half million years ago, perfectly adapted to the cold conditions of the north with short ears and tails to help conserve heat and a thick coat of fur. Unlike their mammoth cousins, these massive herbivores had a specific dietary preference. They were true travellers, ranging from the Alaskan arctic all the way south to Honduras and feeding on branches, shrubs and small trees.

What makes their adaptation truly remarkable is how they managed heat retention in such a brilliant way. Think about it: every part of their anatomy was engineered for survival in brutal cold. Hardy and tough, they were built to withstand the cold temperatures of the north and fend off ice age predators. Their compact features meant less surface area exposed to freezing winds, while that dense fur acted like nature’s own insulated parka. These creatures weren’t just surviving the ice age, they were thriving in it.

Dire Wolves and Their Bone Crushing Bite

The dire wolf wasn’t just some fantasy creature from television shows. Dire wolves were a canine species that hunted the plains and forests, similar to modern grey wolves but heavier, with bigger heads, jaws and teeth giving them a strong bite ideal for killing large prey like camels, horses, and bison. Their adaptation was all about raw power, designed to take down megafauna that would make a modern moose look like a house pet.

Here’s what really sets them apart: their hunting strategy. Dire wolves roamed every inch of North America from the frozen Canadian north down through Mexico and thrived in every imaginable ecosystem from boreal forests to grassland plains to tropical wetlands, hunting in packs of 30 or more and feeding on large prey like mammoths, giant sloths and Ice Age horses. They weren’t picky about climate or habitat, which is honestly impressive when you think about the dramatic environmental shifts happening during their reign. Their ability to coordinate massive pack hunts gave them an edge that even larger predators couldn’t match.

Short Faced Bears Dominating Through Size

In prehistoric North America, the short-faced bear ruled the land. When you think about prehistoric predators, you might imagine saber toothed cats or dire wolves, but these bears were in a league of their own. Giant short-faced bears were the largest carnivorous land mammal to ever live in North America, roughly one and a half times the size of today’s Kodiak grizzly bear.

Their size wasn’t just for show. It gave them a decisive advantage in the competitive world of Ice Age predators. They could intimidate other carnivores away from kills and access food sources that smaller predators simply couldn’t handle. A variety of bears, including Arctodus (the short-faced bear), the most powerful predator of the American Pleistocene, was probably replaced by Ursus arctos — the grizzly bear, which came from Asia at that time. The fact that it took an entirely different bear species migrating from another continent to eventually replace them speaks volumes about their dominance.

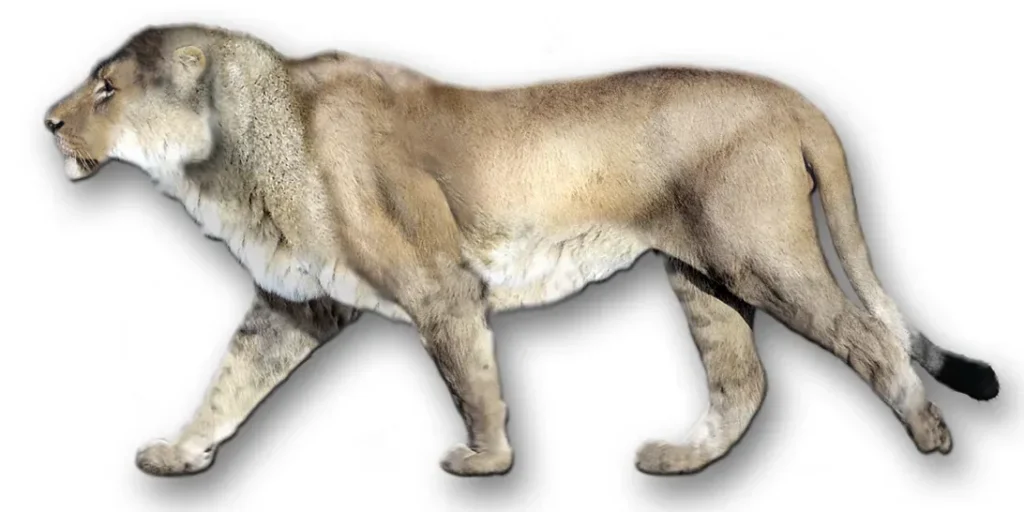

American Cave Lions and Their Massive Frames

Lions in North America? Absolutely. The American cave lion called this continent home and was one of the largest known cats, almost 25 percent bigger than the lions we see in Africa and India today, standing about four feet at the shoulder and weighing up to 420 kilograms. Their sheer size made them apex predators in an already dangerous world.

What’s fascinating is how they may have behaved. Paleolithic art of similar lions found on cave walls in France and Russia show that the prehistoric cats had a faintly striped coat and no mane, unlike modern lions, and scientists think they could have lived in prides, working together to hunt and raise young. If they did hunt cooperatively, imagine the devastation a pride of these massive cats could inflict on prey populations. Prey in the ice age was plentiful; horses, deer, and camels roamed the land in great numbers, which meant these supersized predators had the food supply to sustain their enormous bodies.

Ancient Horses Adapting to Open Grasslands

It is a little known fact that camels originated in North America, and many people are surprised to learn that horses first appeared in North America, with the earliest known ancestral horse in the world living in North America 30 to 50 million years ago. Over millions of years, these early horses underwent one of evolution’s most remarkable transformations.

During the early part of the Eocene the first primitive horses began appearing, with Eohippus being a small animal with four toes on the front feet and three on the rear. As grasslands expanded, horses changed dramatically. Gradually over time horses lost toes, their digits reduced to a single digit, and by the Oligocene their teeth had adapted to endure abrasion from silica in their increasingly grassy diets. Every change reflected the shifting landscape around them, from toe reduction for running on harder ground to specialized teeth for grinding tough grasses. Horses gradually became common throughout the country, spreading wherever grasslands flourished.

Steppe Bison Crossing Ancient Land Bridges

Steppe bison first crossed Beringia around 160,000 years ago, making their way from Europe and Asia to North America. This migration wasn’t just a casual stroll, it represented one of the great mammalian invasions of the Pleistocene. These weren’t the bison you might envision from Old West movies, they were significantly larger and adapted to life in the mammoth steppe ecosystem.

Their adaptation was all about mobility and endurance. Changes in climate and environment caused large-scale migrations of both plants and animals, evolutionary adaptations, and in some cases extinction. Steppe bison had the biological toolkit to handle these shifts. Bison in North America did not go extinct but instead became smaller, most likely as a result of climate change as the last ice age ended and the climate warmed. Their ability to physically transform over relatively short evolutionary timescales is what ultimately saved them from the fate that befell so many other megafauna species.

Prehistoric Plants Surviving Through Disharmonious Environments

In the temperate zones of central Europe and the United States where deciduous forests exist today, vegetation was open and most closely resembled the northern tundra, with grasses, herbs, and few trees during glacial intervals. This created ecosystems unlike anything we see today. Such “disharmonious” faunas suggest that glacial climatic and environmental conditions in some cases were totally unlike those of any modern environment.

Plants had to be incredibly flexible during these periods. Farther south, a broad region of boreal forests with varying proportions of spruce and pine or a combination of both extended almost to northern Louisiana in North America. Species that could tolerate a wide range of conditions, or migrate quickly as temperatures shifted, were the ones that made it through. The drought tolerant plants began to dominate, fundamentally reshaping the continent’s ecology. This wasn’t just about individual species surviving, it was about entire plant communities reorganizing themselves in ways that had never existed before or since.

Riparian Zone Plants Enduring Flash Floods and Grazing

In the western United States, riparian areas comprise less than 1 percent of the land area, but they are among the most productive and valuable natural resources, with the water rich riparian areas and arid uplands being significantly different. Even in prehistoric times, these narrow corridors of vegetation along waterways were critical survival zones for both plants and animals.

The plants that colonized these zones needed remarkable resilience. Plants that live in the riparian zone have adaptations that allow them to survive flash floods, saline soils, and being eaten by the animals coming to the area for water. It’s hard to imagine the evolutionary pressure required to develop such varied defenses simultaneously. You needed deep, flexible root systems to anchor against floodwaters, salt tolerance mechanisms that most plants simply don’t possess, and chemical or physical defenses against constant browsing pressure from thirsty megafauna. Riparian areas are the major providers of habitat for endangered and threatened species in the western desert areas, demonstrating that these corridors have always been biodiversity hotspots.

The prehistoric United States was a laboratory of evolutionary innovation, where survival demanded constant adaptation. From the ice covered plains of Alaska to the subtropical forests of the Deep South, life found ways to persist through dramatic climate swings that would challenge even modern species. These ancient survivors teach you that flexibility, not just strength, is often the key to making it through Earth’s harshest challenges. What’s your take on which adaptation seems most impressive to you?