When you think about prehistoric beasts roaming ancient landscapes, your mind probably jumps straight to dinosaurs. Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, Velociraptors. Yet long after the dinosaurs vanished from Earth, something equally bizarre and magnificent emerged across the Americas. These creatures evolved in isolation, particularly in South America, developing forms so unusual that even Charles Darwin called them some of the strangest animals ever discovered.

During the Late Pleistocene, nearly three-quarters of North American megafauna went extinct, with South America losing over eighty percent of its giant mammals. Before they disappeared, these animals dominated landscapes in ways that would boggle your mind today. Picture armadillos the size of small cars, sloths bigger than elephants, and mammals with body parts borrowed from completely unrelated species. Let’s dive into seven of these mind-bending creatures that prove evolution has a wild imagination.

Megatherium: The Ground Sloth That Stood Like a Giant

Megatherium was an extinct genus of ground sloths from South America that lived from the Early Pliocene through the end of the Late Pleistocene, with the elephant-sized type species primarily known from the Pampas. Honestly, calling this thing a sloth feels like an insult to its sheer magnificence. Megatherium americanum towered over ten feet tall and weighed up to four tons, making modern elephants look modest by comparison.

These beasts weren’t lazy tree-dwellers like their tiny descendants. A ground sloth could walk on its hind legs and spent considerable time reared up while feeding, using its thick tail for balance, reaching branches some twenty feet off the ground with massive claws hooking down branches to eat leaves. Think about that for a second. A four-ton mammal casually standing upright like it was browsing the top shelf at a grocery store. Megatherium fossils have been found with cut marks suggesting ancient humans consumed these giant beasts, though humans and giant ground sloths of Cuba coexisted for about a thousand years.

Glyptodon: The Volkswagen-Sized Armadillo

Let me paint you a picture of absolute absurdity. Glyptodon was an enormous animal, eleven feet long and five feet high, weighing over two tons, with a massive domed carapace like a tortoise shell made of rows of osteoderms. Imagine a modern armadillo hitting the gym for millions of years and developing a shell so thick and heavy it could barely move.

Glyptodonts reached up to five feet in height with maximum body masses around two tonnes, featuring short deep skulls, a fused vertebral column, and a large bony carapace made up of hundreds of individual scutes, with some having clubbed tails similar to ankylosaurid dinosaurs. The thing is, this walking tank wasn’t aggressive. It munched on grass and low plants. Glyptodont skulls are all broken in the same area which may have allowed the animal to be stunned, and an inverted empty glyptodont carapace at Taima-Taima suggests the animal was flipped over before its internal bones and flesh were scooped out. Early humans apparently figured out its one weakness and exploited it brutally.

Toxodon: Darwin’s Impossible Mammal

Charles Darwin described Toxodon as “one of the strangest animals ever discovered”. Here’s the thing about Toxodon that made it so perplexing: it looked like someone threw a hippopotamus, rhinoceros, and maybe an elephant into a blender and hoped for the best. Toxodon platensis was a large-bodied hoofed mammal estimated to weigh more than a tonne and was probably similar in size to the American bison or African black rhino.

What really threw scientists for a loop was its anatomy. Toxodon was about nine feet in body length with an estimated weight up to fifteen hundred kilograms and about five feet high at the shoulder, resembling a heavy rhinoceros with a short and vaguely hippopotamus-like head, and because of the position of its nasal openings it is believed that Toxodon had a well-developed snout. Some experts think it might have had a short trunk. Let that sink in. A rhino-sized mammal with hippo features and possibly a trunk, lumbering around ancient South America eating grass. During the Pleistocene Toxodon was one of the most common herbivores across South America and likely became prey for sabre-toothed cats like Smilodon, with arrowheads found with Toxodon remains virtually proving humans hunted this prey animal.

Macrauchenia: The Camel-Llama With a Trunk

If Toxodon confused scientists, Macrauchenia left them completely baffled for nearly two centuries. Macrauchenia is an extinct genus of large ungulate native to South America from the Pliocene or Middle Pleistocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene. Picture this oddity: The bodyform of Macrauchenia has been described as similar to a camel with an estimated body mass of around one tonne, but it had three-toed feet like a rhino and nostrils positioned on top of its skull between its eyes.

Unlike most mammals the Macrauchenia’s nostril openings were on top of its head above and between the eyes, and experts suggested the retracted nostril means the animal had a trunk or inflated snout similar to the saiga antelope. Why would evolution create such a bizarre arrangement? More recent findings suggest that the retracted nostril was a feeding adaptation, as Macrauchenia and other Litopterns were high browsers feeding on tough and thorny vegetation, and the retracted nostrils would have protected their nose from getting impaled by thorns while reaching for leaves. That’s genuinely clever when you think about it.

The Giant Short-Faced Bear: North America’s Apex Nightmare

The giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) was the largest carnivorous mammal to ever roam North America. Let’s be real here. This wasn’t your average scary bear. Standing on its hind legs an adult giant short-faced bear boasted a vertical reach of more than fourteen feet. Imagine looking up and seeing that towering over you in the twilight of the Ice Age.

The name is actually misleading. Despite its name there was nothing short about this enormous bear, however compared to its long arms and legs it appeared as if it did have a shorter face. The most striking difference between modern North American bears and the giant short-faced bear were its long lean and muscular legs, which has given rise to the idea that it was a cursorial predator meaning that it ran after prey. A bear. That could run you down. Sleep well tonight with that thought.

The Dire Wolf: Not Just a Game of Thrones Fantasy

The popular show Game of Thrones brought the fictional direwolf to the screen depicting them as intimidating beasts, but humans living in ice age North America had to deal with the real thing. Dire wolves (Canis dirus) were a canine species that hunted the plains and forests, similar to modern grey wolves but heavier with bigger heads jaws and teeth giving them a strong bite ideal for killing large prey like camels horses and bison.

Here’s something fascinating that most people don’t know. About six million years ago dire wolves split from wolves making them distant relatives of today’s wolves on the canid family tree. They weren’t just bigger wolves. Because of their size dire wolves ambushed their prey working together to bring down an animal once they had a hold of it, rather than being long-distance runners like modern-day grey wolves. These were pack-hunting ambush predators built like linebackers.

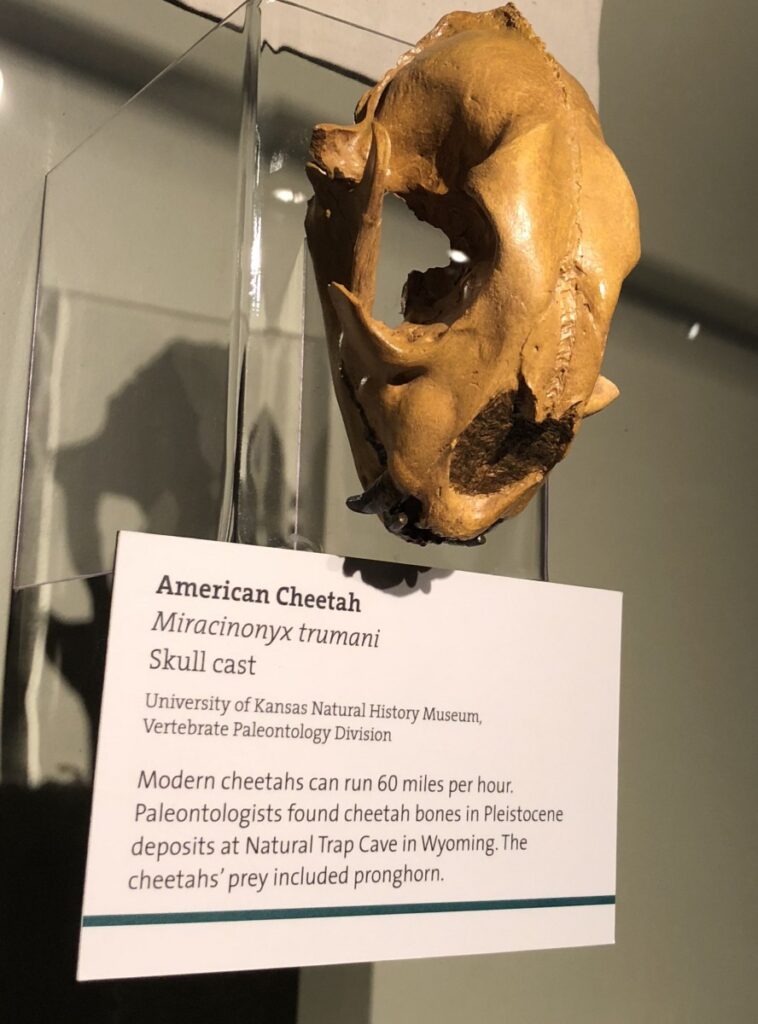

The American Cheetah: Speed Before the Pronghorn Knew It

The American Cheetah lived in North America before the last Ice Age with its bones discovered from West Virginia to Arizona and even Wyoming. Now here’s where it gets interesting and slightly controversial. This big cat was known as the American cheetah (Miracinonyx trumani) and American cheetahs are closely related to modern cougars, not African cheetahs despite the name.

Cheetah is the only genus of cat that ever originated in North America from ancestral felids that immigrated from Asia, and the American cheetah’s recent extinction thirteen thousand years ago is the reason that Pronghorn antelope are the fastest running herbivores in the world running twenty miles per hour faster than their fastest predator. Think about that evolutionary arms race. The pronghorn antelope can still sprint at ridiculous speeds today because it’s running from a ghost. Its predator vanished but the speed remains, a fossil trait embedded in living flesh.

Conclusion

Overall during the Late Pleistocene about sixty-five percent of all megafaunal species worldwide became extinct rising to seventy-two percent in North America and eighty-three percent in South America. These magnificent oddities vanished in what feels like an evolutionary blink. A 2020 study found that human population size and specific human activities not climate change caused rapidly rising global mammal extinction rates during the past 126,000 years with around ninety-six percent of all mammalian extinctions over this time period attributable to human impacts.

We lost an entire world of biological wonder. Ground sloths that stood like bears, armadillos you could use as shelters, mammals with trunks that weren’t elephants, and predators that would make modern apex hunters look timid. These weren’t dinosaurs, but they were every bit as spectacular and bizarre. Perhaps more so, because they shared the world with our ancestors and left us wondering what life would be like if they still roamed the Americas today. What do you think would happen if one of these creatures suddenly appeared in the modern world? Share your thoughts below.