For decades, we pictured dinosaurs as sluggish, cold-blooded monsters dragging their tails through primordial swamps. They were evolutionary failures, doomed to extinction because of their primitive brains and clumsy bodies. Think about how profoundly wrong that image turned out to be.

Over the past few decades, a wave of remarkable fossil discoveries has completely rewritten what we know about how dinosaurs actually lived, moved, and interacted with each other. With the discovery of new specimens and the development of cutting-edge techniques, paleontologists are making major advances in reconstructing how dinosaurs lived and acted. These aren’t just minor tweaks to old theories. We’re talking about fundamental shifts that reveal dinosaurs as dynamic, complex creatures with behaviors we once thought were reserved only for modern mammals and birds. The fossils don’t lie, yet they’ve surprised scientists time and time again. Let’s dive into five groundbreaking finds that flipped our understanding on its head.

They Lived in Complex Social Herds Far Earlier Than We Ever Imagined

Picture a group of long-necked dinosaurs returning to the same nesting ground year after year, with adults watching over clusters of youngsters while other groups foraged nearby. Sounds like something from a nature documentary, right? Here’s the thing: this wasn’t happening during the age of giant sauropods in the Late Jurassic. Researchers from MIT, Argentina, and South Africa say Mussaurus patagonicus may have lived in herds as early as 193 million years ago, 40 million years earlier than other records of dinosaur herding.

Scientists detailed their discovery of an exceptionally preserved group of early dinosaurs showing signs of complex herd behavior, with the team excavating more than 100 dinosaur eggs and the partial skeletons of 80 juvenile and adult dinosaurs from a fossil bed in southern Patagonia. What made this discovery truly remarkable was how the fossils were arranged. When researchers unearthed the remains, they noticed that the younger specimens were grouped together while the adults were in pairs or alone, suggesting that the animal gathered in age-oriented groups, a habit of many larger animals today. It’s honestly hard to wrap your head around the implications here. This is the earliest confirmed evidence of gregarious behavior in dinosaurs, and paleontological understanding suggests if you find social behavior in this type of dinosaur at this time, it must have originated earlier.

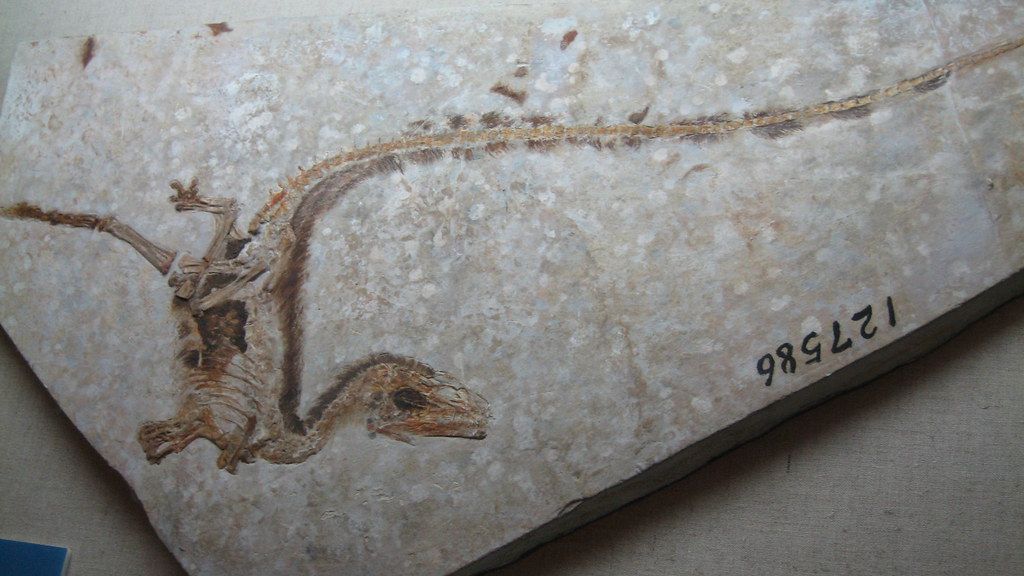

Feathered Dinosaurs Revealed Birds Didn’t Invent Feathers

Let’s be real, when most people think of dinosaurs, they picture scaly reptilian skin, not fluffy feathers. The 1996 discovery of Sinosauropteryx in China shattered that image forever. Sinosauropteryx fulfilled what paleontologists had been looking for: fossilized feathers along the neck, back and tail of the dinosaur left no doubt that birds had evolved from feathery dinosaur ancestors. This wasn’t some early bird ancestor, though. This was a genuine non-avian dinosaur sporting a coat of fuzzy proto-feathers roughly 124 million years ago.

The floodgates opened after that initial find. Almost three decades have passed since Sinosauropteryx’s scientific debut, and experts have discovered dozens more feathered dinosaurs, including bird-like raptors, tyrannosaurs, and even horned dinosaurs with feathers and feather-like body coverings, revealing that fluff and fuzz were widespread among dinosaurs. What’s even more fascinating is that these feathers weren’t always about flight. Paleontologists have found feathers and related structures on many other dinosaurs that never would have flapped into the air, like the 30-foot-long Yutyrannus, where among these flightless dinosaurs plumage had a variety of other functions, from keeping warm to camouflage. Feathers originated and diversified in carnivorous, bipedal theropod dinosaurs before the origin of birds or the origin of flight. Imagine a fuzzy Tyrannosaurus ancestor wandering around looking more like an oversized angry chicken than a movie monster.

Dinosaur Parents Were Surprisingly Devoted Caregivers

Here’s something that might shock you: some dinosaurs were actually pretty good parents. Maiasaura is one of the most famous examples of dinosaur nests and parental behavior, with finding nests with juvenile dinosaur bones suggesting that the hatchlings were cared for by a parent. The name Maiasaura literally means “good mother lizard,” and boy, did these duck-billed dinosaurs earn that title.

In the 1970s, paleontologist Jack Horner discovered what was later dubbed Egg Mountain in Montana, a gigantic fossilized nesting site of hundreds of specimens of duck-billed Maiasaura from up to 80 million years ago, where evidence of trampled eggshells suggests hatchlings were in the nest for a while, and along with the shells there was plant matter in the nests, suggesting parents may have fed the young before they ventured out.

Then there’s the stunning case of the oviraptorids. The spectacular nesting Citipati fossil provides some of the most remarkable evidence of how these dinosaurs incubated their eggs, with the large adult skeleton preserved at the center of a ring of eggs, with its arms wrapped around the precious clutch. Scientists know from previous finds that oviraptorids laid two eggs at a time in a clutch of 30 or more, meaning the mother would have to stay with or at least return to the nest, lay her pair of eggs, arrange them carefully in the circle, and bury them appropriately every day for two weeks to a month. It’s a staggering level of parental investment that completely contradicts the image of dinosaurs as mindless brutes abandoning their eggs like sea turtles.

The Dinosaur Renaissance Began With One Spectacular Fossil

Fifty years ago, in February 1969, John Ostrom, then an assistant professor at Yale, published a paper describing a previously unknown dinosaur he dubbed Deinonychus, meaning terrible claw in Greek, and the paper reignited public interest in dinosaurs and upended common assumptions in the field. Before Deinonychus burst onto the scene, prior to Ostrom, dinosaurs were thought of as large, lumbering, cold-blooded, and slow-witted evolutionary failures.

Deinonychus changed everything. This wasn’t some plodding lizard. Discovering Deinonychus resurrected the hypothesis that birds descended from dinosaurs, with Ostrom postulating that birds were direct descendants of the dinosaurs, rather than simply sharing a common ancestry. The implications rippled through paleontology like an earthquake. Today almost all scientists accept Ostrom’s findings.

This single discovery essentially launched what scientists call the Dinosaur Renaissance, a complete rethinking of dinosaur biology and behavior. The connection between birds and dinosaurs, which had been proposed way back in the 1860s by Thomas Huxley, suddenly had powerful new evidence. Looking at your backyard bird feeder will never be quite the same once you realize those little creatures are genuine living dinosaurs.

The Pack Hunting Debate Revealed Complex Social Dynamics

Did velociraptors hunt in packs like wolves, coordinating attacks with cunning intelligence? It’s one of the most iconic images from Jurassic Park, yet there’s actually not very much direct evidence for pack hunting in dinosaurs, with much of the evidence in favor of pack hunting being circumstantial. The discovery that sparked this whole debate traces back to 1969. Paleontologists found the partial remains of Tenontosaurus alongside at least four similarly shredded Deinonychus, and at that time researchers proposed that the carnivores hunted cooperatively to bring down the herbivore before evidently succumbing to early deaths themselves.

However, when scientists reexamined the evidence decades later, a messier picture emerged. Researchers reexamined the evidence and posit that the incident was altogether more frenzied and less cooperative, with evidence one of the raptors killed another and that they engaged in cannibalism, suggesting they fought over the Tenontosaurus remains. Think less coordinated wolf pack, more chaotic feeding frenzy like modern Komodo dragons converging on a carcass.

Still, newer evidence suggests some tyrannosaurs might have been more social than we imagined. The new Utah site adds to the growing body of evidence showing that tyrannosaurs were complex, large predators capable of social behaviors common in many of their living relatives, the birds, and this discovery should be the tipping point for reconsidering how these top carnivores behaved and hunted. The truth probably lies somewhere in the complicated middle. Not all carnivorous dinosaurs behaved the same way, and social behavior likely varied widely across different species, times, and environments.

Conclusion

The story of dinosaur behavior is far from complete. Every new fossil discovery, every cutting-edge technique, every reexamination of old specimens adds another piece to an enormous puzzle that spans roughly 170 million years. What seemed impossible just a few decades ago – determining the color of dinosaur feathers, proving they cared for their young, establishing their connection to modern birds – is now established science.

Yet honestly, there’s still so much we don’t know and may never know. Did they communicate with complex vocalizations? What were their courtship rituals like? How did different species interact in shared ecosystems? These five discoveries remind us that science is always evolving, always questioning, always ready to overturn long-held assumptions when the evidence demands it. The dinosaurs we thought we knew were mostly fiction. The real creatures that once dominated this planet were far stranger, far more complex, and far more fascinating than we ever gave them credit for. What other secrets are still buried in ancient stone, waiting for someone to unearth them?