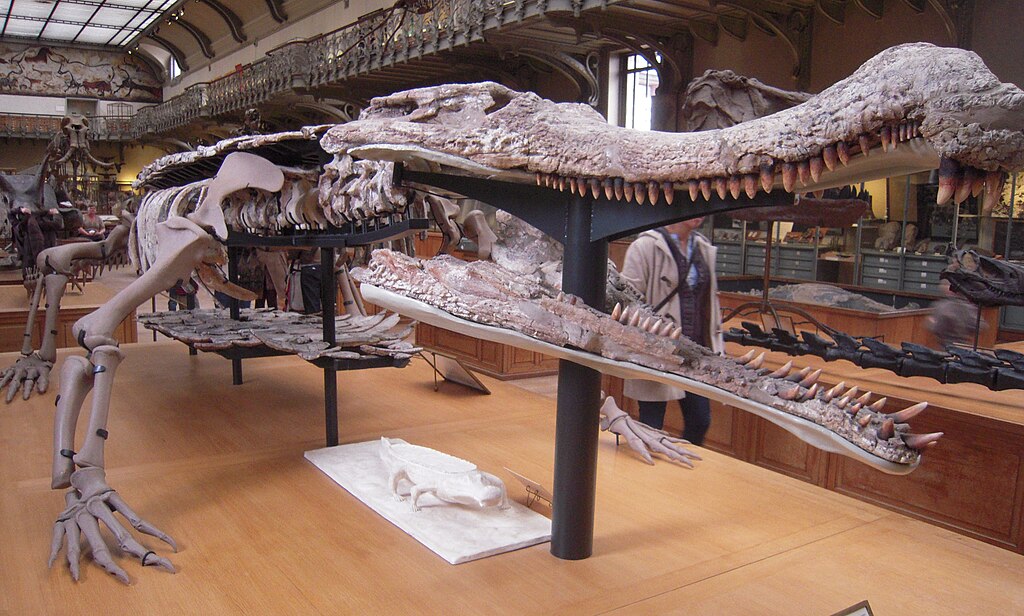

The theft of dinosaur fossils represents a troubling intersection of science, crime, and the black market for natural history treasures. While most people associate dinosaur skeletons with museums and academic institutions, these prehistoric remains have become highly valuable commodities, attracting sophisticated criminal networks. From Mongolia’s Gobi Desert to the American West, dinosaur fossil theft has grown into a multimillion-dollar criminal enterprise that threatens scientific knowledge and cultural heritage. This article explores notable cases, the motivations behind such thefts, and the efforts to combat this specialized form of crime that robs humanity of irreplaceable windows into Earth’s distant past.

The Underground Fossil Market

The illicit trade in dinosaur fossils has exploded in recent decades, with premier specimens fetching millions of dollars at auction houses or through private sales. This underground market operates globally, with fossils often passing through multiple hands to obscure their origins. Private collectors, driven by fascination with prehistoric life or seeing fossils as investment assets, fuel demand for these scientifically invaluable remains. The most sought-after specimens include complete skeletons of iconic dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, and raptors, which can sell for prices rivaling fine art masterpieces. Unlike most stolen goods, fossils can be difficult to authenticate as illegally obtained since documentation of their excavation may be minimal or falsified, complicating enforcement efforts.

The Mongolian Tarbosaurus Case

One of the most infamous dinosaur thefts involved a nearly complete Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton – a close relative of Tyrannosaurus rex – smuggled out of Mongolia and auctioned in New York City in 2012. The 70-million-year-old specimen sold for over $1 million before authorities intervened. Commercial paleontologist Eric Prokopi had illegally imported the 8-foot-tall, 24-foot-long skeleton, claiming it originated from Great Britain when it had actually been poached from Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. The case gained international attention when Mongolia’s president personally requested the skeleton’s return, citing his country’s law declaring all fossils found within its borders as national property. Prokopi eventually pleaded guilty to smuggling charges, earning him a three-month prison sentence. This landmark case highlighted the sophisticated networks behind fossil trafficking and set important legal precedents for fossil repatriation.

The “Dueling Dinosaurs” Controversy

In 2006, commercial fossil hunters discovered an extraordinary specimen in Montana: two dinosaurs—a Tyrannosaurus rex and a Triceratops—preserved together, possibly locked in combat at the time of their deaths. This exceptional find, dubbed the “Dueling Dinosaurs,” became entangled in a complex legal battle over ownership rights that lasted for years. The fossils were excavated from private land, but questions arose about mineral rights versus surface rights, creating a murky legal situation. After failing to sell at auction for the desired $9 million, the specimens remained in storage, inaccessible to scientists, for over a decade. The case illustrated how even legally excavated fossils can become effectively “stolen” from science when commercial interests prevent researchers from studying these irreplaceable specimens. After years of litigation, the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences eventually acquired the specimens in 2020 for public display and research.

Operation Jurassic: Breaking Up a Fossil Smuggling Ring

In 2014, Brazilian and French authorities collaborated on “Operation Jurassic,” a massive effort to dismantle an international fossil smuggling network operating in the Araripe Basin of northeastern Brazil. This operation resulted in the seizure of thousands of fossils, including rare pterosaur remains, that had been illegally excavated from protected sites. The criminal organization had established an elaborate system for extracting, processing, and exporting these specimens to collectors and dealers worldwide. Many of the recovered fossils represented species new to science or specimens of exceptional preservation quality that would have commanded high prices on the black market. The operation revealed how smugglers often recruited local residents with detailed knowledge of fossil sites but limited economic opportunities, highlighting the socioeconomic factors that sometimes drive fossil poaching. Brazilian authorities have since strengthened enforcement measures at known fossil localities and border checkpoints.

The Sue Saga: From Criminal Case to Museum Centerpiece

The discovery and subsequent legal battle over “Sue,” the most complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton ever found, exemplifies the complex issues surrounding fossil ownership. In 1990, commercial fossil hunter Sue Hendrickson discovered the specimen on a South Dakota ranch owned by Maurice Williams, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. The fossil hunters paid Williams $5,000 for the right to excavate the skeleton, but federal authorities later seized the fossils, claiming they had been taken from federal land held in trust for the tribe. The ensuing legal battles involved multiple parties claiming ownership rights and culminated in a federal auction where Chicago’s Field Museum purchased Sue for $8.36 million in 1997, funded by corporate sponsors. While not a theft in the traditional sense, the Sue case illustrates the murky legal territory and competing claims that often surround valuable dinosaur remains, particularly in the United States where laws regarding fossil ownership vary by land type and jurisdiction.

Laws and Loopholes: The Legal Framework

The legal landscape governing fossil collection and trade varies dramatically worldwide, creating opportunities for exploitation. In the United States, fossils found on private land generally belong to the landowner, while those discovered on federal lands are protected as public resources. This patchwork of regulations creates confusion that fossil thieves readily exploit. Countries like Mongolia, China, and Argentina have enacted strict laws declaring all fossils national property regardless of where they’re found, though enforcement remains challenging. Many nations lack specific legislation addressing fossil poaching, instead relying on general heritage protection or smuggling laws. A significant loophole exists in the international system: a fossil illegally excavated in one country may be legally purchased in another if the buyer can claim ignorance of its illicit origins. The absence of a comprehensive international framework specifically addressing fossil trafficking continues to hamper efforts to protect paleontological resources globally.

Techniques of the Fossil Thieves

Dinosaur fossil thieves employ sophisticated methods that have evolved beyond simple smash-and-grab operations. Professional poachers often use geological surveys and satellite imagery to identify promising dig sites, sometimes even monitoring legitimate paleontological expeditions to discover productive locations. The extraction process frequently involves heavy equipment like jackhammers and bulldozers, which can severely damage contextual information critical to scientific understanding. After excavation, thieves typically transport specimens to preparation facilities where technicians carefully remove surrounding rock and stabilize the fossils—work requiring considerable expertise. To circumvent export restrictions, larger specimens are often broken into smaller fragments, labeled as rock samples or common fossils, and shipped through multiple countries to obscure their origin. Some operations have become so sophisticated that they create false documentation, including fabricated permits and provenance histories, to legitimize stolen specimens once they reach the commercial market.

Scientific Impact of Fossil Theft

When dinosaur fossils are stolen or improperly excavated, science suffers irreparable losses beyond the physical specimens themselves. Professional paleontologists carefully document the position, orientation, and geological context of each bone during excavation—critical data that reveals information about the animal’s environment, behavior, and cause of death. Fossil thieves typically ignore this contextual information in their rush to extract valuable specimens, permanently destroying potential knowledge. Additionally, stolen fossils that disappear into private collections become inaccessible to researchers, creating gaps in the scientific record that may never be filled. Perhaps most damaging is when poachers discover specimens of previously unknown species that never reach scientific description, effectively keeping these prehistoric creatures hidden from human knowledge. The scientific community has documented numerous cases where commercially collected specimens showed features that would have significantly altered existing understanding of dinosaur biology had they been properly studied.

The Gobi Desert: Hotspot for Dinosaur Theft

Mongolia’s Gobi Desert represents one of the world’s richest dinosaur fossil regions and, unfortunately, a primary target for fossil poachers. This vast, sparsely populated region contains exceptionally preserved specimens from the Late Cretaceous period, including iconic dinosaurs like Velociraptor, Protoceratops, and various theropods. The remote nature of the Gobi, combined with limited resources for patrolling its expansive territories, creates ideal conditions for illegal excavation. Sophisticated smuggling networks have established routes through neighboring China, where fossils may be prepared before entering international markets with falsified documentation. The problem escalated so severely that Mongolia implemented a specialized “dinosaur unit” within its law enforcement agencies, tasked specifically with combating fossil theft. International cooperation has improved in recent years, with major auction houses and museums now conducting more rigorous provenance checks on Mongolian specimens, though looting continues in more isolated areas where enforcement remains challenging.

Returning the Giants: Repatriation Efforts

Recent years have witnessed unprecedented efforts to return stolen dinosaur fossils to their countries of origin. The United States Department of Homeland Security has played a pivotal role, collaborating with international partners to seize and repatriate illegally exported specimens. Mongolia has been particularly successful in these initiatives, recovering numerous important fossils including several complete Tarbosaurus skeletons from American and European collectors. The repatriation process typically involves complex legal battles and diplomatic negotiations, sometimes lasting years before resolution. Museums worldwide have also begun re-examining their collections for potentially questionable acquisitions, with some institutions voluntarily returning fossils of dubious provenance. These returns often become matters of national pride in the receiving countries, with repatriated specimens featured prominently in new museum exhibitions. While progress has been made, challenges remain in identifying stolen fossils already in collections and establishing clear ownership for specimens acquired decades ago under different legal frameworks.

The Commercial-Academic Divide

The fossil world has long been divided between commercial collectors who view fossils primarily as commodities and academic paleontologists who prioritize their scientific value. This divide became particularly pronounced in the 1990s when commercial dinosaur hunting evolved into a lucrative industry, exemplified by the record-breaking sale of Sue the T. rex. Commercial collectors argue they recover specimens that might otherwise erode away undiscovered, while academics counter that scientifically valuable context is often lost during commercial excavations. This tension manifests in heated debates at paleontological conferences, competing legislation efforts, and occasional collaboration when commercial finds are donated to institutions. Some museums have adopted policies against purchasing commercially collected specimens, while others maintain relationships with reputable commercial preparators. The philosophical divide extends to questions about who should “own” natural history—private individuals who can afford to purchase specimens, or the public through scientific institutions that make them available for research and education.

Digital Protection: Technology in Fossil Crime Prevention

Technological innovations are increasingly employed to combat dinosaur fossil theft and trafficking. Satellite monitoring now allows authorities to detect unauthorized activities at known fossil localities, triggering rapid response from enforcement teams. Many museums and research institutions have implemented sophisticated database systems containing detailed photographs, 3D scans, and unique identifying characteristics of specimens in their collections, making stolen fossils easier to identify when they appear on the market. DNA and isotope analysis techniques can now determine the geographical origin of some fossils, helping authenticate questionable specimens. Some countries have begun embedding microscopic trackers or ultraviolet-reactive markers in vulnerable specimens, creating an invisible signature that survives even if the fossil is broken into pieces. Blockchain technology has also been proposed as a solution for tracking fossil provenance through a tamper-proof digital record of ownership transfers. Despite these advances, technological solutions remain challenging to implement across remote fossil-rich regions where resources are limited.

Community-Based Conservation Success Stories

Some of the most effective approaches to preventing dinosaur fossil theft involve local communities as partners in conservation efforts. In Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, the Mongolian Paleontological Center has trained local nomadic herders to recognize and report suspicious excavation activities, creating a network of citizen monitors across vast territories impossible to patrol conventionally. Similar programs in Argentina’s Patagonia region employ local residents as site guardians, providing sustainable income alternatives to the temptation of selling information to fossil poachers. Several Native American tribes in the western United States have established their own paleontological programs, combining scientific methods with traditional perspectives on stewardship of ancient remains. Community museums in fossil-rich regions of Morocco and Brazil allow locals to benefit economically from paleontological tourism while ensuring specimens remain accessible for scientific study. These participatory approaches recognize that sustainable protection of fossil resources requires addressing the economic realities facing communities where these irreplaceable treasures are found.

The Future of Fossil Protection

Protecting dinosaur fossils from theft will require multifaceted approaches adapting to evolving challenges. International legal frameworks specifically addressing fossil trafficking are gaining momentum, with organizations like UNESCO considering special protections for paleontological heritage similar to those for archaeological sites. Educational initiatives targeting collectors about ethical sourcing may help reduce market demand for questionable specimens. Technological solutions continue advancing, with promising developments in remote monitoring systems and forensic techniques for fossil authentication. The commercial fossil industry itself is showing signs of reform, with more dealers implementing stringent documentation requirements and refusing specimens from countries with clear export prohibitions. Museum policies increasingly emphasize provenance research and transparency about acquisition histories. Perhaps most encouraging is the growing public awareness of fossil theft as a serious crime against science and heritage, not merely a regulatory violation. This cultural shift, combined with stronger enforcement and international cooperation, offers hope for better protecting these irreplaceable windows into Earth’s distant past.

Conclusion

The theft of dinosaur fossils represents a unique form of crime with far-reaching consequences for science, education, and our understanding of Earth’s history. Unlike traditional art theft, where the stolen object itself holds primary value, fossil theft destroys contextual information critical to scientific knowledge – information that can never be recovered. As dinosaur remains continue appreciating in commercial value, the battle between preservation and exploitation intensifies. However, encouraging developments in international cooperation, technology, community involvement, and legal frameworks offer promising paths forward. By recognizing fossils not merely as collectible curiosities but as irreplaceable scientific data and cultural heritage, we can work toward ensuring these ancient giants remain where they belong – in the public trust, accessible to researchers and wonder-struck visitors for generations to come.