The hunting behaviors of dinosaurs have fascinated paleontologists and the public alike for generations. Among the most compelling questions is whether certain dinosaur species engaged in coordinated pack hunting, similar to modern wolves or lions, or if they were merely opportunistic feeders that gathered around carcasses. Recent fossil discoveries and advanced analytical techniques have begun to shed new light on this ancient mystery. Evidence ranging from fossil trackways to bone beds with multiple predator remains suggests that some dinosaur species may indeed have hunted cooperatively, though the degree of their social sophistication remains debated. This article explores the evidence for and against pack hunting in various dinosaur species, examining how modern research is changing our understanding of dinosaur behavior.

The Challenge of Interpreting Prehistoric Behavior

Determining the social behaviors of extinct animals presents unique challenges for paleontologists. Unlike modern behavioral studies, where scientists can directly observe animals in their natural habitats, researchers studying dinosaurs must rely on indirect evidence preserved in the fossil record. Fossilized bones, tracks, bite marks, and geological contexts provide the primary data points for reconstructing dinosaur behavior. These fragments from the past require careful interpretation, and conclusions about complex behaviors like pack hunting must be drawn cautiously. Additionally, the fossil record is inherently incomplete, creating information gaps that scientists must navigate. Despite these limitations, paleontologists have developed increasingly sophisticated methods for analyzing the evidence, including comparative anatomy with modern animals, biomechanical modeling, and taphonomic studies of fossil assemblages.

Deinonychus: Early Evidence for Cooperative Hunting

The early Cretaceous predator Deinonychus antirrhopus provided some of the first compelling evidence for potential pack hunting among dinosaurs. In the 1960s, paleontologist John Ostrom discovered multiple Deinonychus specimens in association with the remains of a much larger herbivorous dinosaur, Tenontosaurus. This discovery suggested that several Deinonychus individuals may have died while attacking a single large prey animal. The size disparity between predator and prey, with Deinonychus weighing approximately 160 pounds and Tenontosaurus around 1-2 tons, further strengthened the case for cooperative hunting. A solitary Deinonychus would have faced significant challenges in taking down such large prey, making group hunting a more plausible strategy. The discovery revolutionized views of dinosaur behavior, challenging the then-prevalent image of dinosaurs as slow, solitary creatures.

Velociraptor: Fact vs. Fiction

Few dinosaurs have captured the public imagination quite like Velociraptor, largely due to its portrayal as a pack-hunting predator in the Jurassic Park franchise. However, the scientific evidence for pack hunting in Velociraptor is more limited than popular culture suggests. The most famous Velociraptor fossil, discovered in Mongolia in 1971, shows a specimen locked in combat with a Protoceratops, suggesting at least some predatory behavior. But evidence specifically supporting pack hunting remains sparse for this genus. The Velociraptor depicted in films is also substantially larger than the actual dinosaur, which stood about knee-height to an adult human and weighed around 33 pounds. While Velociraptor was certainly a predator with impressive physical adaptations, including a sickle-shaped claw and relatively large brain, paleontologists remain cautious about attributing complex social hunting behaviors to this dinosaur without more definitive evidence.

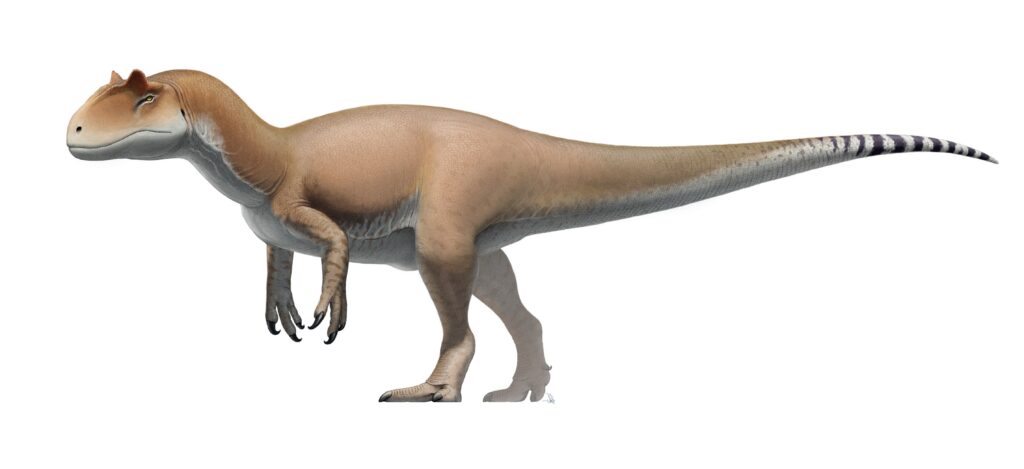

The Mapusaurus Bone Bed: A Smoking Gun?

One of the most compelling cases for pack hunting comes from a remarkable fossil site in Argentina containing multiple specimens of the massive theropod Mapusaurus. Discovered in the late 1990s and described in 2006, this bone bed contained the remains of at least seven Mapusaurus individuals of varying ages, all preserved together without evidence of a catastrophic event that might have killed them simultaneously. These enormous predators, larger than Tyrannosaurus rex, were found near the remains of their likely prey, the enormous sauropod Argentinosaurus—possibly the largest dinosaur ever to have lived. The case for pack hunting here is particularly compelling, as even these massive predators would have struggled to take down a full-grown Argentinosaurus individually. Cooperative hunting would have provided an evolutionary advantage, allowing these carnivores to tackle prey that would otherwise be too dangerous or difficult for a solitary hunter.

Allosaurus: The Serengeti Scenario

The Late Jurassic predator Allosaurus has been at the center of discussions about dinosaur hunting behavior due to remarkable fossil discoveries at the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in Utah. This site has yielded remains of at least 46 Allosaurus individuals of various ages, raising questions about why so many predators were preserved in one location. Some paleontologists have proposed that this represents evidence of pack behavior, with multiple Allosaurus hunting together or, at minimum, feeding communally. Others suggest these aggregations might represent a “Serengeti scenario,” where multiple carnivores were attracted to seasonal die-offs of herbivores or drought-stricken watering holes. The debate intensified with the discovery of multiple Allosaurus trackways moving in the same direction at roughly the same time. While not definitive proof of coordinated hunting, these trackways indicate that Allosaurus at least tolerated the presence of conspecifics, which would be a prerequisite for any form of cooperative behavior.

Tyrannosaurus rex: King of Opportunists?

Despite its fearsome reputation, the hunting behavior of Tyrannosaurus rex remains particularly contentious in paleontological circles. Some studies suggest T. rex was primarily a scavenger rather than an active hunter, pointing to its massive size, relatively short arms, and keen sense of smell as adaptations more suited to finding carrion than chasing prey. However, most paleontologists now favor a model where T. rex functioned as both predator and scavenger as opportunities arose, similar to modern large carnivores like lions. The evidence for pack hunting in T. rex is limited and controversial. While some fossil sites show multiple T. rex individuals nearby, these could represent competition at feeding sites rather than cooperative behaviors. In 2021, research on a T. rex mass mortality site in Utah suggested possible social behavior, but whether this extended to coordinated hunting remains speculative. The massive bite force and robust build of T. rex may have made it perfectly capable of taking down large prey individually, potentially reducing any selective pressure toward cooperative hunting.

Utahraptor: The Pack-Hunting Case Strengthens

The discovery of the “Utahraptor megablock” in eastern Utah has provided some of the most compelling evidence yet for pack behavior in dromaeosaurid dinosaurs. This remarkable fossil find contains the remains of at least six Utahraptor individuals of different ages, from juvenile to adult, all preserved together. Paleontologists believe these individuals became trapped in quicksand-like conditions while potentially hunting together, providing a rare snapshot of dinosaur social structure. Utahraptor, significantly larger than its relative Velociraptor, possessed the physical characteristics that would make pack hunting advantageous, including large sickle claws, strong forelimbs for grasping, and binocular vision. The presence of multiple individuals of different age groups suggests a family group or persistent social unit rather than a temporary gathering of opportunistic feeders. This discovery has strengthened the case that at least some dromaeosaurids lived and hunted in cooperative social groups.

Lessons from Modern Pack Hunters

To better understand potential pack hunting in dinosaurs, paleontologists often look to modern pack-hunting species for insights and analogies. Contemporary pack hunters like wolves, lions, and spotted hyenas display specific anatomical and behavioral traits that facilitate cooperative hunting. These include enhanced communication abilities, relatively large brains, social hierarchies, and often sexual dimorphism. Some theropod dinosaurs show similar anatomical features, including relatively large brain-to-body ratios and sensory adaptations that could support complex social behaviors. However, important differences remain between dinosaurs and modern mammalian pack hunters. Mammals invest heavily in parental care and typically have long periods of learning and development, facilitating the transmission of complex behaviors across generations. Whether dinosaurs had comparable capacities for behavioral learning remains unknown. Additionally, the energetic demands of endothermy (warm-bloodedness) in mammals often necessitate cooperative hunting strategies, while the metabolic rates of various dinosaur groups remain debated.

The Alternative: Mobbing Behavior

Not all group predatory behavior constitutes true pack hunting, and paleontologists have proposed alternative models that might explain dinosaur fossil assemblages without requiring sophisticated coordination. One such model is mobbing behavior, where multiple predators opportunistically converge on a single prey item without coordinated planning or attack strategies. This behavior is observed in modern Komodo dragons and crocodilians, which may gather around large carcasses or wounded prey. In these scenarios, the predators are competing rather than cooperating, though they tolerate each other’s presence up to a point. Some dinosaur fossil assemblages previously interpreted as evidence of pack hunting might instead represent this form of congregative feeding. Distinguishing between true pack hunting and mobbing behavior in the fossil record presents significant challenges, as both might leave similar patterns of multiple predators associated with prey remains. More refined analytical techniques and additional fossil discoveries will be necessary to differentiate between these behavioral possibilities.

The Role of Track Evidence

Fossilized trackways provide some of the most direct evidence of dinosaur behavior, offering snapshots of animals in motion rather than just their remains after death. Several significant dinosaur trackway discoveries have revealed multiple individuals of the same species moving in the same direction at approximately the same time. In Korea, a remarkable set of theropod tracks shows at least three medium-sized carnivorous dinosaurs moving parallel to one another at a steady pace. Similar parallel trackways have been found for both herbivorous and carnivorous dinosaurs at sites around the world. While these trackways don’t definitively prove pack hunting, they strongly suggest that some dinosaur species at least tolerated proximity to others of their kind and potentially traveled together. Track evidence also helps establish that certain dinosaur species were at minimum gregarious, forming groups for purposes that might have included mutual protection, migration, or possibly coordinated hunting activities. However, trackway evidence must be interpreted cautiously, as parallel tracks could form for reasons unrelated to social behavior, such as physical barriers channeling movement or multiple individuals following the same optimal path.

Specialized Roles in Dinosaur Packs

If some dinosaurs did hunt in packs, they may have developed specialized roles within their social groups similar to those observed in modern pack hunters. In wolf packs, different individuals often perform specific functions during a hunt—some chase and harass prey while others move to intercept or ambush. Some paleontologists have suggested that certain dinosaur species could have exhibited similar role specialization, particularly in groups containing individuals of different ages and sizes. For instance, the smaller, more agile juveniles of large theropods might have flushed out or harassed prey, while larger adults delivered killing blows. This hypothesis is supported by growth studies of some theropods, which show dramatic changes in proportions and presumably hunting capabilities as they mature. The presence of different age classes in some dinosaur assemblages, such as the Utahraptor site, provides circumstantial evidence for potential role differentiation. However, proving such complex behavioral dynamics in extinct animals remains extremely challenging and largely speculative in the absence of direct observational evidence.

The Evolution of Social Behavior in Theropods

The evolution of potential pack-hunting behavior in theropod dinosaurs raises fascinating questions about the development of social complexity in these ancient reptiles. If some dinosaurs did indeed hunt cooperatively, this behavior would have required substantial cognitive capabilities, communication skills, and social tolerance—traits traditionally associated more with mammals and birds than with reptiles. Interestingly, birds (the living descendants of theropod dinosaurs) exhibit a wide range of social behaviors, including cooperative hunting in some species, like Harris’s hawks. This evolutionary connection suggests that the neurological and behavioral foundations for complex social interactions might have deep roots in theropod dinosaur lineages. The discovery of enlarged brain regions associated with higher cognitive functions in some theropods, particularly maniraptoran dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Troodon, further supports the possibility that these animals possessed the neural hardware necessary for sophisticated social behaviors. Some researchers propose that pack hunting may have evolved multiple times within different theropod lineages as a response to specific ecological pressures, rather than representing a singular evolutionary innovation.

Implications for Dinosaur Ecology

Whether certain dinosaurs hunted in packs has profound implications for understanding Mesozoic ecosystems and predator-prey dynamics. Pack hunting would have significantly expanded the range of potential prey species available to theropod dinosaurs, allowing relatively modest-sized predators to take down much larger herbivores. This hunting strategy could help explain how medium-sized theropods coexisted with the massive sauropods and other large herbivores that dominated many Mesozoic landscapes. Cooperative hunting behavior would also have influenced prey defense strategies, potentially driving the evolution of herding behaviors, defensive weaponry, and other anti-predator adaptations in herbivorous dinosaurs. If pack hunting was widespread among certain theropod groups, it would suggest more complex and dynamic ecosystems than previously recognized, with sophisticated behavioral interactions shaping the evolutionary arms race between predators and prey. Understanding these behavioral dynamics provides crucial context for interpreting the remarkable diversity of dinosaur forms that evolved throughout the Mesozoic Era.

Continuing Debates and Future Research

The question of dinosaur pack hunting remains actively debated in paleontological circles, with ongoing research continuously refining our understanding. New analytical techniques are helping scientists extract more information from existing fossils. For example, histological studies of bones can reveal growth patterns and age structures within fossil assemblages, potentially distinguishing family groups from random aggregations. Advanced scanning technologies allow researchers to examine the brain cases of theropod fossils, providing insights into sensory capabilities and regions associated with social cognition. Computer modeling of biomechanics helps determine whether cooperative hunting would have provided significant advantages for particular dinosaur species. Future discoveries will undoubtedly continue to transform our understanding of dinosaur behavior. Particularly valuable would be the discovery of additional mass mortality sites with clear taphonomic contexts, more extensive trackway sequences, and fossils preserving direct predator-prey interactions. As research methods advance and new evidence emerges, our picture of dinosaur social behavior will continue to evolve, potentially resolving the long-standing question of whether some dinosaurs were indeed sophisticated pack hunters or merely opportunistic feeders.

Conclusion: A Spectrum of Social Behaviors

Rather than a simple binary question of whether dinosaurs were pack hunters or opportunists, the evidence increasingly suggests a spectrum of social behaviors existed across different dinosaur species and families. Some theropods likely were solitary hunters throughout most of their lives, while others may have exhibited various degrees of social tolerance or cooperation. Certain species, particularly within the dromaeosaurid and carcharodontosaurid families, show compelling evidence for at least some form of group living and potentially coordinated hunting. However, the sophistication of these behaviors—whether they constituted true pack hunting with role specialization or simpler forms of cooperative feeding—remains difficult to establish with certainty. As with modern animals, dinosaur social behavior was likely influenced by numerous factors, including ecology, prey type, body size, and evolutionary history. The ongoing refinement of analytical methods and discovery of new fossils continues to provide glimpses into the complex social lives of these fascinating creatures, gradually bringing the behavioral ecology of dinosaurs into sharper focus. What remains clear is that dinosaurs were far more behaviorally complex than once believed, with social capabilities that in some cases may have rivaled those of modern predators.