Popular culture has long portrayed dinosaurs as colossal beasts that dominated prehistoric landscapes. Films, books, and exhibitions typically showcase massive creatures like Tyrannosaurus rex or Brachiosaurus, reinforcing the notion that “dinosaur” is synonymous with “gigantic.” However, paleontological discoveries reveal a far more diverse reality. While some dinosaurs indeed reached breathtaking proportions, many species were surprisingly small—some no larger than modern chickens. These diminutive predators were often just as fearsome and evolutionarily successful as their larger relatives, challenging our understanding of dinosaur diversity and demonstrating nature’s remarkable range of adaptations.

The Misconception of Universal Dinosaur Gigantism

The popular imagination typically envisions dinosaurs as towering creatures that shook the earth with each step, but this represents only part of the dinosaur story. This misconception largely stems from early paleontological discoveries that favored the preservation and recovery of larger specimens, creating a sampling bias in the fossil record. Additionally, museums historically preferred displaying larger, more spectacular fossils to draw crowds, further cementing the association between dinosaurs and enormous size. Media portrayals, from “Jurassic Park” to children’s books, have continued reinforcing this size-centric narrative. In reality, dinosaurs exhibited remarkable size diversity throughout their 165-million-year reign, with many species evolving to fill ecological niches that favored smaller body types.

Microraptor: The Four-Winged Wonder

Among the most fascinating small dinosaurs was Microraptor, a crow-sized dromaeosaur that lived approximately 120 million years ago in what is now northeastern China. With an estimated length of just 77 centimeters (2.5 feet) and weighing less than a kilogram, this diminutive predator possessed four wings—feathered structures on both its arms and legs—making it a remarkable example of evolutionary experimentation. Microraptor’s wings featured asymmetrical flight feathers similar to those of modern birds, suggesting it could glide or possibly engage in limited powered flight. Its small size allowed it to pursue insects, small mammals, and possibly fish, as evidenced by stomach contents discovered in some specimens. Despite its modest dimensions, Microraptor’s predatory adaptations included sharp teeth and sickle-shaped claws, demonstrating that predatory effectiveness wasn’t exclusively tied to size.

Compsognathus: The “Elegant Jaw” That Fooled Scientists

Compsognathus holds a special place in paleontological history as one of the first small dinosaurs to challenge the “bigger is better” narrative. Discovered in the 19th century in Germany, this turkey-sized theropod measured approximately 70 centimeters (2.3 feet) in length and weighed only about 3.5 kilograms (7.7 pounds). Its name, meaning “elegant jaw,” references its delicate skull structure perfectly adapted for catching small prey. Interestingly, when first discovered, scientists mistakenly classified Compsognathus as an abnormally large lizard rather than a dinosaur, so entrenched was the belief that all dinosaurs were massive. Stomach content analysis revealed that Compsognathus preyed upon small lizards, demonstrating its role as an active predator in its ecosystem. This diminutive hunter moved quickly on powerful hind legs, balancing with a long tail, embodying the predatory adaptations that would later evolve further in birds.

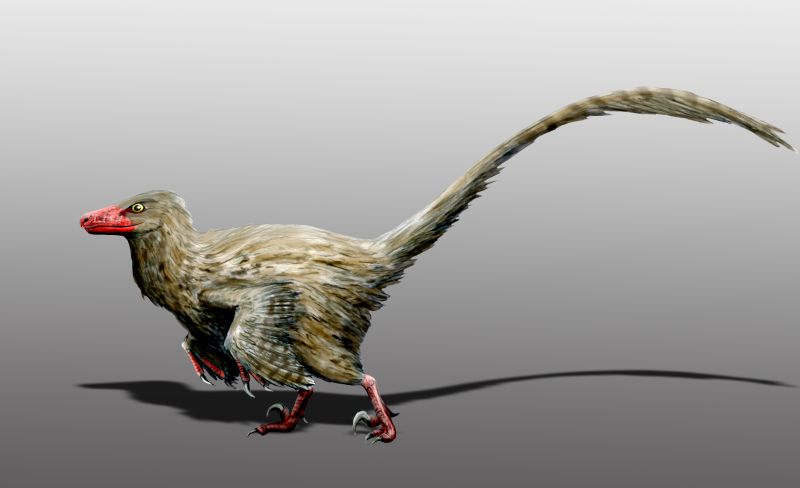

Velociraptor: Not As Depicted in Hollywood

Few dinosaurs have suffered more misrepresentation in popular culture than Velociraptor, which the “Jurassic Park” franchise portrayed as human-sized, when actual fossils tell a very different story. The real Velociraptor mongoliensis stood approximately 50 centimeters (1.6 feet) tall at the hip and measured about 2 meters (6.8 feet) long, with most of that length coming from its extended tail. Weighing approximately 15 kilograms (33 pounds)—comparable to a modern turkey—this predator was far smaller than its silver screen counterpart. Despite its modest size, Velociraptor possessed formidable hunting equipment, including a large, sickle-shaped claw on each foot capable of slashing prey, and jaws filled with serrated teeth. Recent studies confirm that Velociraptor was covered in feathers, further aligning it with modern birds. The famous “fighting dinosaurs” fossil, showing a Velociraptor locked in combat with a Protoceratops, demonstrates that even small dinosaurs engaged in dramatic predatory behavior.

Epidexipteryx: The Bizarre Feathered Oddity

One of the strangest small dinosaurs yet discovered, Epidexipteryx hui represents an evolutionary experiment that defies easy categorization. This pigeon-sized creature, measuring just 25-30 centimeters (10-12 inches) in length, lived approximately 160 million years ago in what is now Inner Mongolia, China. Epidexipteryx belonged to the scansoriopterygid family and possessed several bizarre features, including four long, ribbon-like tail feathers that may have served as display structures for attracting mates. Unlike many feathered dinosaurs, Epidexipteryx had simple, hair-like feathers rather than complex structures for flight, suggesting its feathers served purposes related to insulation or display rather than aerial locomotion. The creature’s elongated fingers and proportionally large eyes hint at a possible tree-dwelling lifestyle, where it may have hunted insects or other small prey. This chicken-sized oddity demonstrates how dinosaurs filled diverse ecological niches with specialized adaptations regardless of their size.

Hesperonychus: North America’s Smallest Killer

Discovered in Alberta, Canada, Hesperonychus elizabethae represents the smallest known carnivorous dinosaur from North America, challenging the notion that all predatory dinosaurs on the continent were substantial in size. This cat-sized dromaeosaurid lived approximately 75 million years ago and weighed just 1.9 kilograms (4.2 pounds), with a length of about 0.9 meters (3 feet). Despite its diminutive stature, Hesperonychus possessed the characteristic sickle-shaped killing claw on its second toe, suggesting it employed hunting tactics similar to its larger relatives. The discovery of this tiny predator in 2009 filled an important gap in understanding North American dinosaur ecology, as it demonstrated that small predatory niches were occupied by dinosaurs rather than early mammals throughout the Cretaceous period. Hesperonychus likely hunted insects, small mammals, and possibly even juvenile dinosaurs, proving that small size didn’t equate to being lower on the food chain.

Anchiornis: The Feathered Pioneer

Anchiornis huxleyi represents one of paleontology’s most complete small dinosaur specimens, providing unprecedented insights into the appearance of these diminutive predators. Living approximately 160 million years ago in what is now China, this crow-sized dinosaur measured about 34 centimeters (13 inches) in length and weighed roughly 110 grams (4 ounces). Remarkably well-preserved fossils of Anchiornis include impressions of feathers with their original coloration patterns, allowing scientists to create accurate visual reconstructions showing a creature with a dark gray body, white feathers on its limbs, and a reddish crown of feathers on its head. This small predator is considered a transitional form between dinosaurs and birds, possessing feathers on all four limbs similar to Microraptor. Anchiornis likely used its feathers for insulation and display before the evolution of flight, demonstrating the complex evolutionary path that eventually led to modern birds.

Ecological Advantages of Being Small

The prevalence of chicken-sized dinosaurs throughout the Mesozoic Era suggests that diminutive stature offered distinct evolutionary advantages in certain ecological contexts. Smaller bodies require less energy to sustain, allowing these dinosaurs to survive on fewer resources and potentially thrive in environments where larger species might struggle during periods of scarcity. Their reduced size enabled them to occupy specialized niches, such as hunting in dense undergrowth or pursuing prey in environments inaccessible to larger predators. Small dinosaurs could also more effectively regulate body temperature due to their higher surface-area-to-volume ratio, potentially giving them greater activity levels and metabolic efficiency. Additionally, smaller size often correlates with faster reproductive cycles and population growth, allowing these species to recover more quickly from environmental disturbances. These combined advantages explain why small dinosaurs diversified and persisted successfully alongside their more massive relatives throughout dinosaur evolutionary history.

Parvicursor: The Miniature Sprinter

Among the most diminutive of all known dinosaurs, Parvicursor remotus (“small runner from a remote place”) embodied the extreme miniaturization possible within dinosaur evolution. Discovered in Mongolia and dating to approximately 75-85 million years ago, this minuscule theropod measured just 39 centimeters (15 inches) in length and likely weighed less than a pound, making it smaller than many modern birds. Despite its tiny size, Parvicursor possessed highly specialized anatomical features, including exceptionally long hind limbs relative to its body size, suggesting it was capable of rapid movement. This small predator belonged to the Alvarezsauridae family, characterized by short, powerful arms with a single enlarged claw, possibly used for breaking into insect nests. Parvicursor’s extreme miniaturization demonstrates how dinosaurs explored the lower limits of body size while maintaining the predatory adaptations characteristic of theropods, further proving that evolutionary success wasn’t solely determined by size.

Mahakala: The Time-Traveling Tiny Terror

Mahakala omnogovae represents a paleontological time capsule that helps scientists understand the early evolution of dromaeosaurids, the family including Velociraptor and other “raptor” dinosaurs. Living approximately 80 million years ago in what is now Mongolia, this chicken-sized predator measured just 70 centimeters (2.3 feet) in length. What makes Mahakala particularly significant is that it retained primitive features from earlier in dromaeosaurid evolution despite living relatively late in the Cretaceous period. This suggests that small body size was likely the ancestral condition for dromaeosaurids, with larger species evolving later—contrary to the popular narrative that dinosaurs generally grew larger over evolutionary time. Mahakala possessed the characteristic enlarged sickle claw on its second toe, reinforcing that this specialized killing adaptation appeared early in dromaeosaurid evolution regardless of body size. The persistence of this small predator alongside larger relatives demonstrates how different-sized predators could coexist by specializing in different prey or hunting strategies.

Yi qi: The Dinosaur That Almost Became a Bat

Perhaps one of the strangest small dinosaurs ever discovered, Yi qi (pronounced “ee chee”) represents an evolutionary experiment that took dinosaurs in an unexpected direction. Living approximately 160 million years ago in what is now China, this pigeon-sized creature weighed less than a pound but possessed one of the most unusual anatomical features yet found in any dinosaur: membranous wings supported by an elongated wrist bone, similar to the structure seen in modern bats. This adaptation is entirely different from the feather-based wings of birds and other dinosaurs, suggesting Yi qi evolved a completely separate solution for aerial locomotion. The creature’s name means “strange wing” in Mandarin, aptly describing its bizarre anatomy. While paleontologists debate whether Yi qi could truly fly or merely glide, its small size would have been advantageous for any aerial lifestyle, requiring less muscle power to become airborne. This chicken-sized oddity demonstrates how small dinosaurs experimented with diverse body plans and ecological strategies, exploring evolutionary pathways that larger species could not.

The Evolution of Small Size in Dinosaurs

The prevalence of small dinosaurs throughout the Mesozoic Era raises important questions about the evolutionary pressures driving miniaturization in certain lineages. Contrary to the popular notion of dinosaurs consistently evolving toward larger sizes—a phenomenon known as Cope’s Rule—paleontological evidence reveals numerous cases of dinosaur lineages becoming smaller over time, particularly within the theropod group that eventually gave rise to birds. This miniaturization trend accelerated in the maniraptoran theropods, with successive generations evolving progressively smaller body sizes alongside anatomical adaptations like hollow bones, increased brain size relative to body mass, and modified forelimbs. These changes allowed small dinosaurs to exploit new ecological niches, particularly arboreal environments that were inaccessible to larger species. The evolutionary trajectory toward smaller body sizes ultimately produced the anatomical framework necessary for powered flight, culminating in the evolution of birds—the only dinosaur lineage to survive the end-Cretaceous extinction event. This evolutionary history demonstrates that becoming smaller rather than larger proved to be the more successful long-term strategy for dinosaurian survival.

Modern Birds: The Living Legacy of Small Dinosaurs

The approximately 10,000 species of modern birds represent the living legacy of small, predatory dinosaurs, offering a direct window into the evolutionary success of miniaturized theropods. The transition from small, feathered dinosaurs to the first true birds occurred gradually, with creatures like Archaeopteryx demonstrating intermediate features between non-avian dinosaurs and modern birds approximately 150 million years ago. This evolutionary continuum is so seamless that paleontologists now classify birds as a specialized group of theropod dinosaurs that survived the mass extinction event 66 million years ago. Modern research has identified numerous anatomical features shared between small dinosaurs and living birds, including wishbones, three-toed feet, hollow bones, nest-building behavior, and egg-brooding. When we observe a chicken today, we are essentially looking at a modified dinosaur that retains the basic body plan of its small theropod ancestors, albeit with specialized adaptations for flight and modern ecological niches. The evolutionary success of birds—the most diverse group of land vertebrates alive today—stands as testament to the adaptive advantages of the small dinosaur body plan.

Conclusion

The dinosaur family tree was populated not just by giants but by an incredible diversity of small, specialized predators that were every bit as evolutionarily successful as their larger relatives. From the crow-sized Microraptor with its four wings to the bat-like experiment Yi qi, these chicken-sized killers demonstrate nature’s remarkable ability to explore diverse evolutionary pathways. The miniaturization trend in certain dinosaur lineages ultimately produced birds—the only dinosaurs to survive to the present day and one of the most successful vertebrate groups on Earth. Far from being evolutionary sideshows, these small dinosaurs represent a crucial chapter in the history of life on our planet, challenging us to expand our conception of dinosaurs beyond the giants that dominate museum halls and popular imagination. In the evolutionary race, it was ultimately the small, feathered dinosaurs that proved most adaptable, surviving the cataclysm that extinguished their larger relatives and continuing their remarkable evolutionary journey into the present day.