Towering over the ancient landscapes of Central Asia, Indricotherium represents one of nature’s most impressive evolutionary marvels. This colossal mammal, which roamed Earth during the Oligocene epoch approximately 34 to 23 million years ago, holds the distinguished title of being the largest land mammal ever to have existed. Standing taller than a giraffe and weighing more than several elephants combined, this gentle giant browsed treetops in prehistoric forests long before humans walked the Earth. Despite its impressive size, Indricotherium remains relatively unknown to the general public compared to dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures. Let’s explore the fascinating world of this magnificent beast, examining its discovery, physical characteristics, habitat, and the mysteries that still surround this ultimate example of mammalian gigantism.

Discovery and Naming Controversy

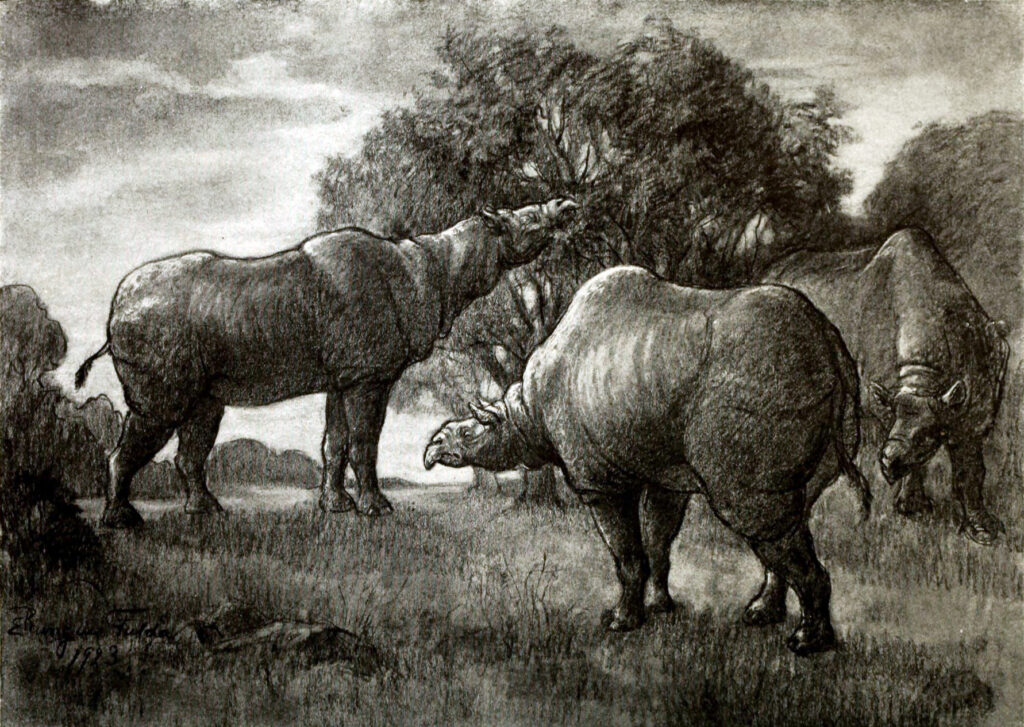

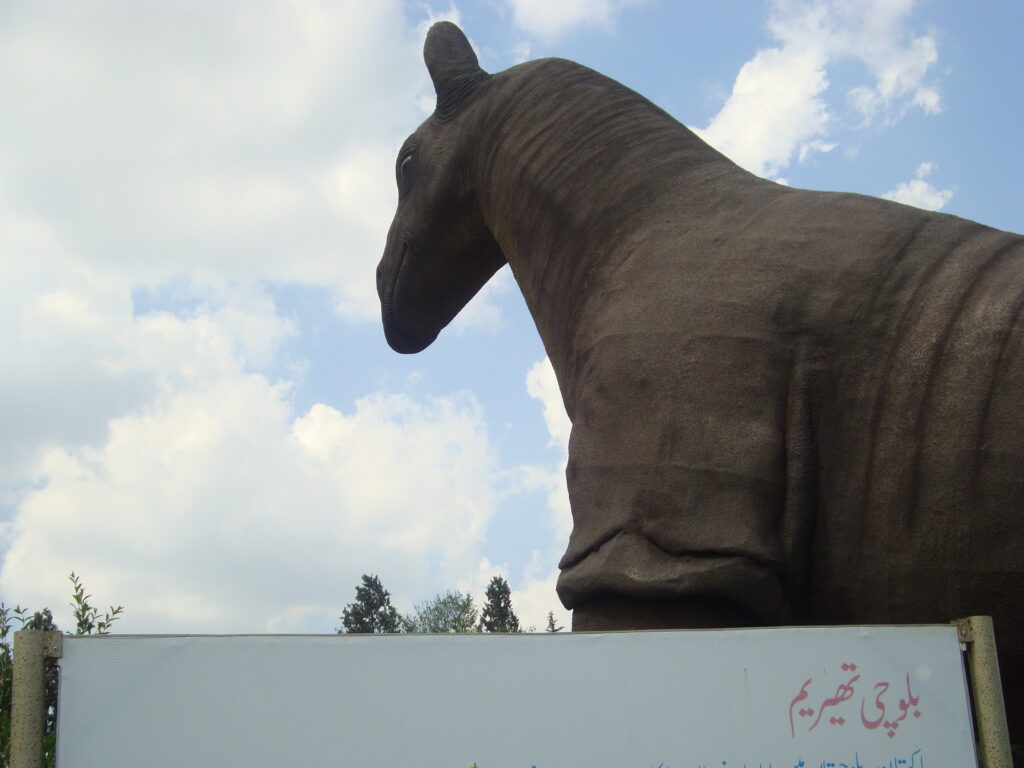

The story of Indricotherium begins with a naming controversy that persists to this day among paleontologists. The giant was first described scientifically in the early 20th century, with fossils discovered in Central Asia during expeditions led by American paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn. Initially named Baluchitherium by Clive Forster Cooper in 1913 based on remains found in Baluchistan (now part of Pakistan), it was later also named Paraceratherium by other researchers. The confusion deepened when similar fossils discovered in Mongolia were named Indricotherium by Soviet paleontologists. Today, many scientists use these names interchangeably, though Paraceratherium has gained preference in much of the scientific literature. The naming dispute reflects the fragmentary nature of the fossil record and the challenge of determining whether slight variations represent different species or simply individual differences within the same species.

Evolutionary Lineage

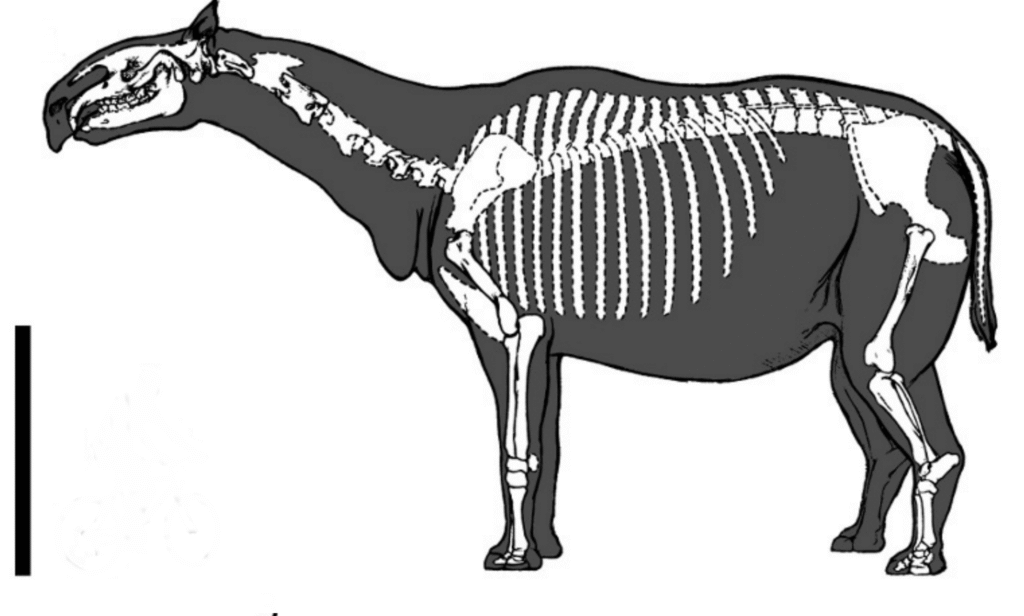

Indricotherium belongs to the family Hyracodontidae, making it an ancient relative of modern rhinoceroses, though far larger and lacking a horn. These massive mammals evolved from smaller ancestors during a period when mammals were diversifying rapidly following the extinction of the dinosaurs. They represent an extreme case of evolutionary gigantism, a process where animals evolve to become significantly larger than their ancestors. Unlike the rhinoceroses we know today, Indricotherium had a more elongated neck, longer legs, and a body design that favored reaching high vegetation rather than the bulldozer-like build of modern rhinos. Their evolutionary path demonstrates how mammals filled ecological niches left vacant after the dinosaurs disappeared, with some lineages exploring the advantages of extreme size in the absence of large predators.

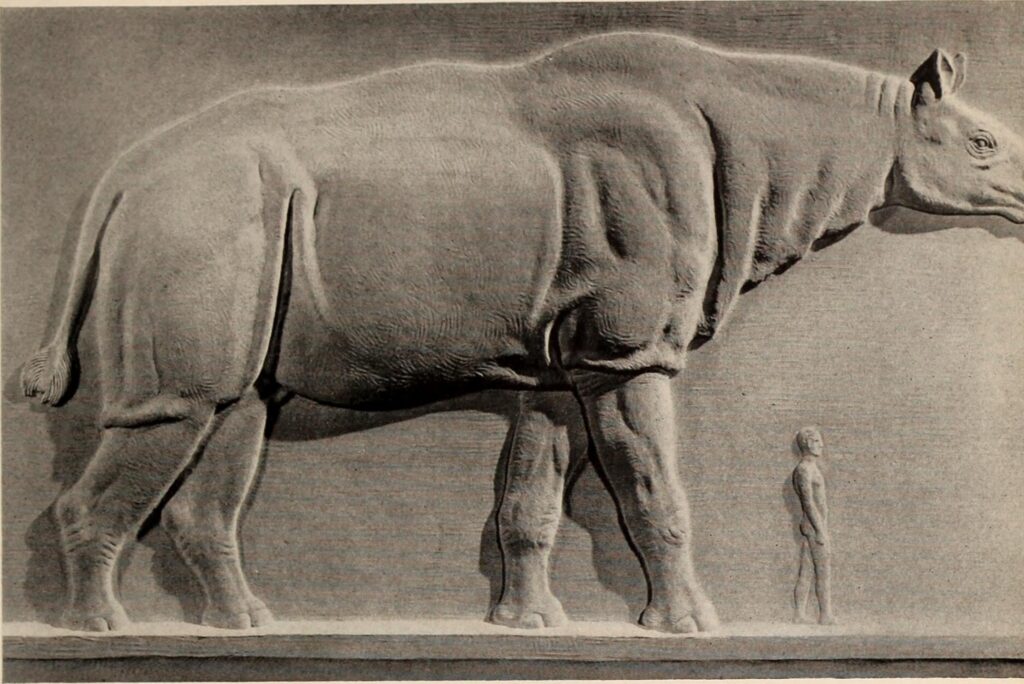

Record-Breaking Dimensions

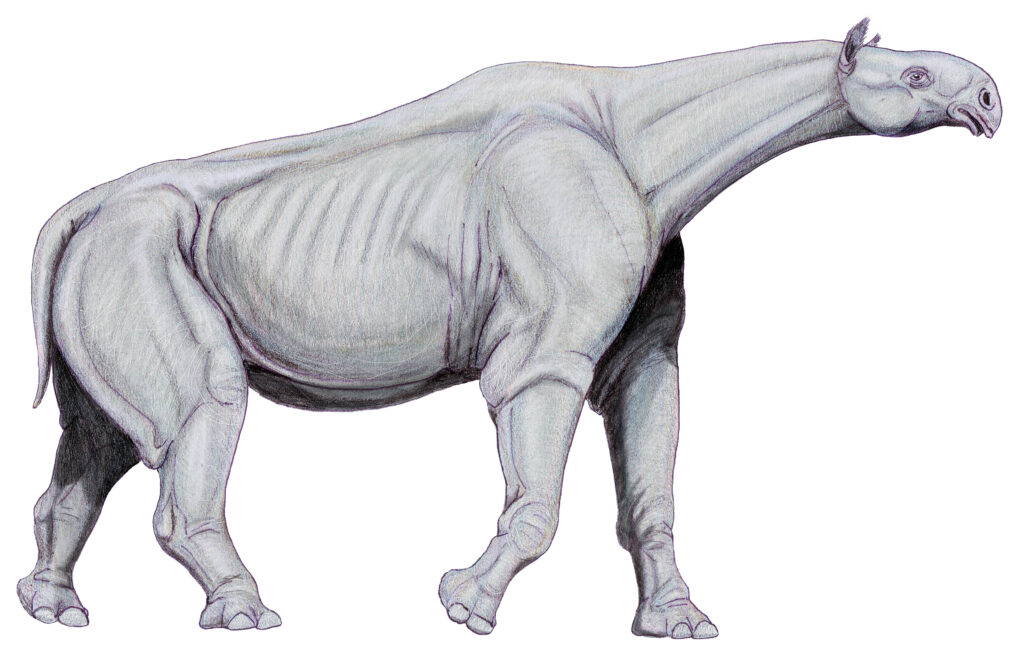

The sheer size of Indricotherium sets it apart in the annals of mammalian evolution. Conservative estimates place these giants at around 15 to 18 feet (4.5 to 5.5 meters) tall at the shoulder, with the ability to reach vegetation up to 26 feet (8 meters) high when stretching their necks. Their body length stretched approximately 25 to 27 feet (7.5 to 8.2 meters) from nose to tail. Weight estimates range from 15 to 20 tons, making them at least three times heavier than modern African elephants. To put this in perspective, you could stack three or four large elephants to approximate the mass of a single Indricotherium. Despite these staggering dimensions, the animal managed to support itself on four pillar-like legs that evolved specifically to bear such tremendous weight, with adaptations in bone density and muscle attachment that allowed for efficient movement despite its massive frame.

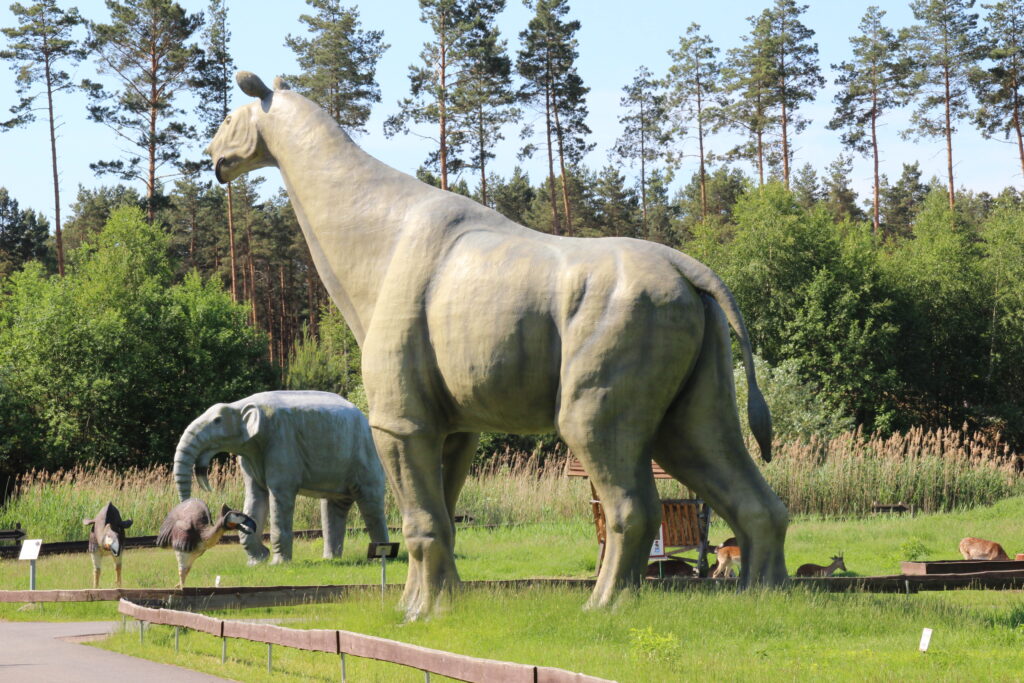

Physical Characteristics

Indricotherium possessed a distinctive appearance unlike any mammal alive today. Its head was relatively small compared to its massive body, with a long, mobile upper lip that likely functioned similarly to a short trunk for grasping vegetation. Unlike modern rhinoceroses, it had no horns, instead featuring a long, sloping forehead. Its teeth were specialized for browsing, with high-crowned molars adapted for processing tough plant material. The neck was elongated, though not to the extent seen in giraffes, allowing the animal to reach high into the canopy of prehistoric forests. Its legs were columnar and straight to support its immense weight, while its feet featured three toes on each foot, similar to its rhinoceros relatives but scaled up dramatically. The overall body shape resembled a massively supersized version of today’s tapirs or hornless rhinoceroses, adapted for a high-browsing lifestyle.

Habitat and Geographic Range

Fossil evidence indicates that Indricotherium inhabited a vast territory across what is now Central Asia, with remains discovered in Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, China, and other neighboring regions. During the Oligocene epoch, when these giants thrived, the environment in these areas was markedly different from today’s landscapes. The habitat consisted primarily of open woodlands and savanna-like environments, quite unlike the arid steppes and deserts that characterize much of the region now. The climate was generally warmer and more humid than present conditions, supporting abundant vegetation that could sustain such enormous herbivores. The geographic distribution of Indricotherium fossils suggests these animals may have undertaken seasonal migrations following food availability, moving across vast territories in herds or small family groups to exploit the most productive feeding grounds as seasons changed.

Feeding Habits and Diet

The specialized anatomy of Indricotherium provides clear evidence of its feeding strategy as a high-level browser. Its towering height allowed it to access foliage that was unavailable to other contemporary herbivores, creating a unique ecological niche that supported its massive size. Dental analysis indicates these giants primarily consumed leaves, shoots, and possibly fruits from tall trees, particularly favoring the foliage of prehistoric relatives of modern beeches, oaks, and birches. Their teeth showed adaptations for processing relatively soft vegetation rather than tough grasses, with high-crowned molars capable of processing large volumes of plant material efficiently. Scientists estimate that a full-grown Indricotherium would need to consume hundreds of pounds of vegetation daily to maintain its enormous body mass, spending most of its waking hours feeding, similar to modern elephants but on an even greater scale.

Reproductive Biology

The reproductive strategies of Indricotherium remain largely speculative due to the limitations of the fossil record, though scientists can make educated inferences based on modern relatives and ecological principles. Like other large mammals, Indricotherium likely had a long gestation period, possibly extending over 18-24 months based on comparisons with elephants and rhinos. Given their massive size, calves were probably relatively well-developed at birth, perhaps weighing hundreds of pounds – enormous by mammalian standards but still only a fraction of adult size. The tremendous investment in each offspring suggests they likely had long intervals between births and produced few calves throughout their lifetime. Maternal care was almost certainly extended, with juveniles remaining with their mothers for several years while they grew and learned feeding behaviors, similar to the pattern seen in modern elephants and other megafauna with complex social structures.

Predators and Threats

Adult Indricotherium likely faced few natural predators due to their immense size, essentially existing at the top of their ecosystem’s size hierarchy. However, younger individuals or weakened adults may have been vulnerable to pack-hunting carnivores of the era, particularly hyaenodonts and creodonts – predatory mammals that preceded modern carnivores. The most significant threats to Indricotherium populations probably came not from predation but from environmental challenges, including drought, disease, and competition for resources during periods of ecological stress. Their specialized feeding requirements made them particularly vulnerable to changes in vegetation patterns, as they needed vast quantities of browse from tall trees to sustain themselves. This ecological specialization, while advantageous during stable periods, likely contributed to their eventual extinction when climatic conditions began shifting toward cooler, drier patterns that favored grasslands over forests.

Social Behavior

The social structure of Indricotherium remains one of the most speculative aspects of their biology, as behavior rarely fossilizes. However, by examining ecological constraints and the patterns seen in modern megaherbivores, paleontologists have developed plausible theories about their social lives. Given their massive size and correspondingly large home ranges needed to supply adequate food, Indricotherium likely lived in loose associations rather than tight herds. They might have gathered in small family groups consisting of related females and their offspring, with mature males living solitarily except during breeding seasons. Communication probably involved low-frequency vocalizations that could travel long distances through their woodland habitats, similar to the infrasound used by modern elephants. Social bonds between mothers and calves were likely strong and enduring, reflecting the extended period of maternal care required for offspring to reach independence in such large-bodied mammals.

Extinction Theories

The disappearance of Indricotherium from the fossil record approximately 23 million years ago has prompted various theories about what led to its extinction. The leading hypothesis centers on climate change during the late Oligocene and early Miocene epochs, when global cooling led to the spread of grasslands at the expense of the woodlands these browsers depended upon. As their specialized food sources became increasingly scarce, Indricotherium populations likely declined gradually over thousands of generations. Their enormous size, once an advantage for reaching high vegetation and deterring predators, became a liability when food resources diminished, as they required vast quantities of browse to sustain themselves. Additionally, their reproductive strategy of producing few, resource-intensive offspring made population recovery difficult during periods of environmental stress. Unlike smaller mammals that could adapt more quickly to changing conditions, these giants represented an evolutionary experiment that ultimately proved unsustainable in Earth’s changing ecosystems.

Famous Fossil Discoveries

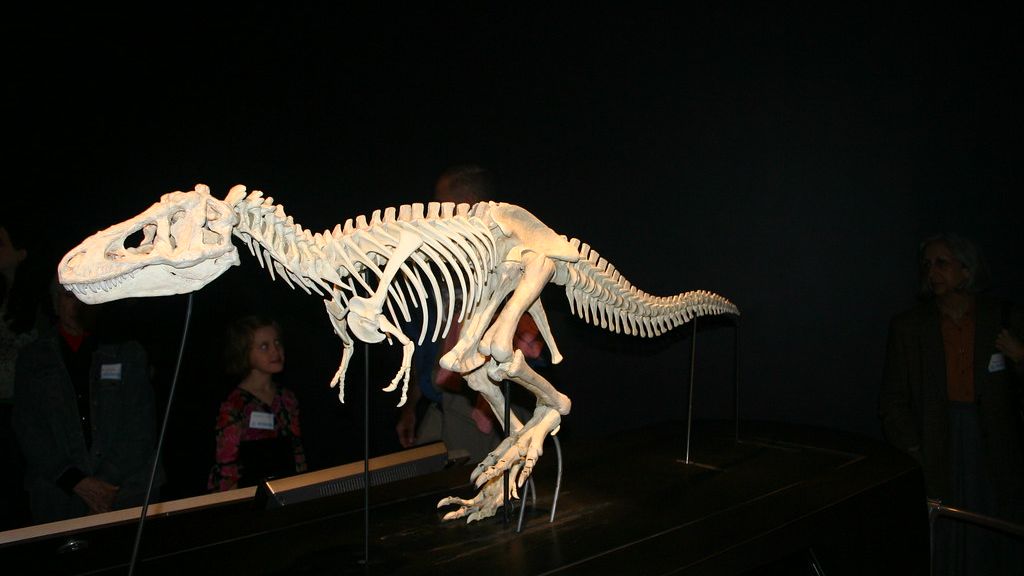

The quest to understand Indricotherium has been marked by several landmark fossil discoveries that progressively revealed the true nature of this colossal mammal. The most celebrated finds came during the Central Asiatic Expeditions led by Roy Chapman Andrews for the American Museum of Natural History in the 1920s, which recovered significant remains from the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. These expeditions captured public imagination and brought Indricotherium to widespread attention for the first time. Later, Soviet paleontological expeditions in Kazakhstan during the mid-20th century unearthed more complete specimens that allowed for better size estimates and anatomical understanding. More recently, discoveries in Pakistan and China have expanded our knowledge of regional variations within the genus. Despite these significant finds, a complete skeleton remains elusive, with most reconstructions based on composite information from multiple partial specimens discovered across Central Asia over the past century.

Scientific Reconstruction Challenges

Accurately reconstructing the appearance and biology of Indricotherium presents unique challenges to paleontologists due to the fragmentary nature of available fossils. Complete skeletons have never been found, forcing scientists to assemble composite images from partial remains discovered across different locations and potentially representing different subspecies or closely related forms. This uncertainty has led to ongoing debates about basic aspects of their anatomy, including precise height, weight, and body proportions. Soft tissue features such as skin texture, coloration, and external ear size remain entirely speculative, typically inferred from modern rhinoceros relatives. The challenge of visualizing these animals accurately extends to museums and educational media, where artistic license often fills gaps in scientific knowledge. Each new fossil discovery has the potential to significantly revise our understanding of these giants, making Indricotherium reconstruction an evolving scientific narrative rather than a settled picture.

Indricotherium in Popular Culture

Despite holding the record as the largest land mammal ever, Indricotherium has received relatively little attention in popular culture compared to dinosaurs and ice age mammals like mammoths and saber-toothed cats. The creature made a memorable appearance in the BBC documentary series “Walking with Beasts,” which introduced many viewers to this prehistoric giant for the first time through computer-generated recreations. In museum exhibits, Indricotherium skeletons and life-sized models serve as centerpieces that consistently amaze visitors with their scale, though such displays are relatively rare due to the incomplete nature of available fossil material. Children’s books about prehistoric life occasionally feature these giants, typically emphasizing their record-breaking size as a point of fascination. The relative obscurity of Indricotherium in popular media may partly stem from its appearance during the Oligocene – a period that falls between the more widely popularized dinosaur era and the ice age megafauna that coexisted with early humans.

Modern Research and New Insights

Contemporary paleontological research continues to refine our understanding of Indricotherium through advanced analytical techniques unavailable to earlier generations of scientists. Modern methods, including CT scanning of fossils, reveal internal bone structures that provide insights into growth patterns, weight-bearing adaptations, and evolutionary relationships. Stable isotope analysis of tooth enamel now allows researchers to determine aspects of diet and habitat use with unprecedented precision, revealing seasonal patterns in feeding behavior. Comparative studies with living megaherbivores, particularly elephants and rhinoceroses, provide frameworks for understanding physiological challenges faced by mammals of extreme size. Digital modeling and biomechanical analysis help scientists understand how these giants moved efficiently despite their massive weight, with recent studies suggesting they may have been more agile than previously thought. The application of ancient DNA techniques remains mostly aspirational for Indricotherium due to the age and preservation conditions of available fossils, though advancements in molecular paleontology continue to push the boundaries of what information might be recoverable from specimens of this age.

Conclusion

Indricotherium stands as a remarkable testament to the extraordinary potential of mammalian evolution. These gentle giants, though extinct for over 20 million years, continue to captivate scientists and the public alike with their record-breaking dimensions and the questions they raise about the upper limits of terrestrial animal size. Their story reminds us that Earth’s history includes creatures that stretch beyond what we might imagine possible, yet operate according to the same biological principles that govern life today. As research techniques continue to advance, we may yet uncover more secrets about how these magnificent animals lived, moved, and ultimately disappeared from our planet. The legacy of Indricotherium lives on not only in museum halls and scientific journals but also in our understanding of evolutionary processes and the complex interplay between organism size, ecological specialization, and environmental change – lessons that remain relevant as we consider the future of Earth’s remaining megafauna in our rapidly changing world.