The vast expanse of prehistoric time harbored creatures so remarkable that they continue to capture our imagination today. Among these ancient beings, prehistoric reptiles stand as some of the most fascinating organisms to have ever roamed the Earth. Their legacy extends beyond mere scientific interest, inspiring countless tales of mythical dragons across human cultures. These formidable creatures, with their armored bodies, impressive size, and sometimes terrifying appearance, provided the biological blueprint that would later manifest in folklore as fire-breathing dragons. From the massive dinosaurs to the flying pterosaurs and marine reptiles that dominated ancient oceans, the connection between prehistoric reality and mythological fantasy reveals how human cultures processed and interpreted fossil evidence long before modern paleontology developed. This article explores the fascinating evolutionary journey of ancient reptiles and examines how their physical characteristics and behaviors may have influenced the dragon myths that persist to this day.

The Dawn of Reptilian Dominance

Reptiles first emerged during the late Carboniferous period, approximately 312 million years ago, evolving from amphibian ancestors that had already colonized land. This evolutionary leap represented a critical milestone in vertebrate development, as reptiles possessed amniotic eggs that could be laid on land, freeing them from water dependency for reproduction. The Permian period (299-251 million years ago) witnessed reptiles diversifying and establishing themselves as the dominant terrestrial vertebrates, occupying ecological niches that would later be filled by mammals and birds. These early reptiles, though relatively modest in size compared to their later descendants, already exhibited key features that would become hallmarks of reptilian success: scales, claws, and specialized teeth. Their adaptability to various environments laid the groundwork for the reptilian golden age that would follow in the Mesozoic Era, setting the stage for creatures that would later inspire dragon myths worldwide.

Dinosaurs: The Ultimate Dragon Prototypes

Of all prehistoric reptiles, dinosaurs perhaps contributed most significantly to dragon mythology across cultures. These remarkable creatures, which dominated terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years, exhibited traits strikingly similar to traditional dragon depictions. The massive theropods like Tyrannosaurus rex, with their powerful jaws lined with razor-sharp teeth, embodied the fearsome predatory aspect associated with many dragon legends. Meanwhile, the armored ankylosaurs and stegosaurs, with their defensive plates and spikes, mirrored the heavily armored bodies described in numerous dragon tales. Particularly noteworthy were the crested dinosaurs such as Parasaurolophus and Dilophosaurus, whose head ornaments bear r remarkable resemblance to the horned heads of dragons in Asian mythology. When early humans discovered dinosaur fossils, they lacked the scientific framework to identify them as extinct animals, instead interpreting these massive bones as evidence of dragons that once roamed their lands. This misinterpretation formed a crucial link between natural history and mythology that persists in our cultural consciousness today.

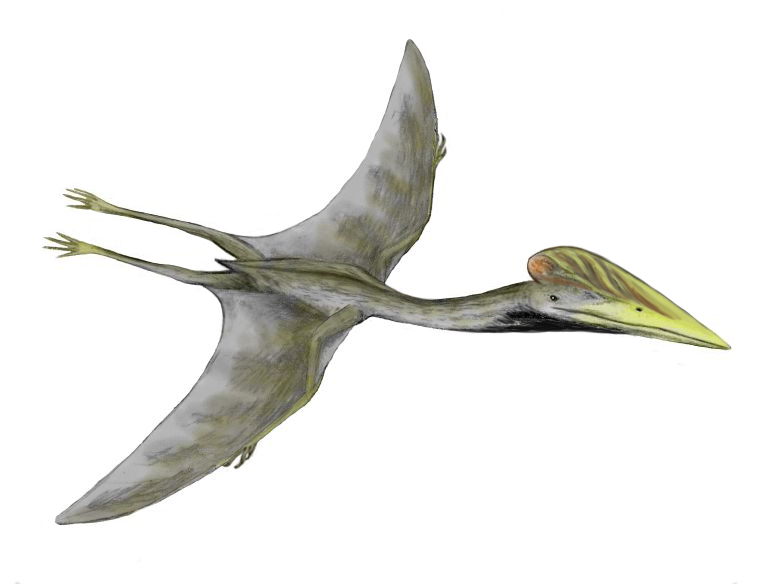

The Masters of the Sky: Pterosaurs

While dinosaurs certainly influenced terrestrial dragon imagery, pterosaurs—the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight—contributed significantly to the concept of flying dragons. These remarkable reptiles, though not dinosaurs, emerged in the late Triassic period and dominated the skies throughout the Mesozoic era until their extinction 66 million years ago. With wingspans ranging from a mere 25 centimeters in the smallest species to over 10 meters in giants like Quetzalcoatlus, pterosaurs embodied the aerial majesty often attributed to mythical dragons. Their unusual anatomy, featuring elongated fourth fingers that supported leathery wing membranes, closely parallels the wing structure described in Western dragon mythology. Particularly influential were the pterosaurs with cranial crests, such as Pteranodon and Tapejara, whose distinctive head shapes may have inspired the elaborate head ornamentations seen in dragon art across cultures. When ancient peoples discovered pterosaur fossils, these strange winged creatures with teeth and claws would have seemed to confirm legends of flying serpents and dragons that ruled prehistoric skies.

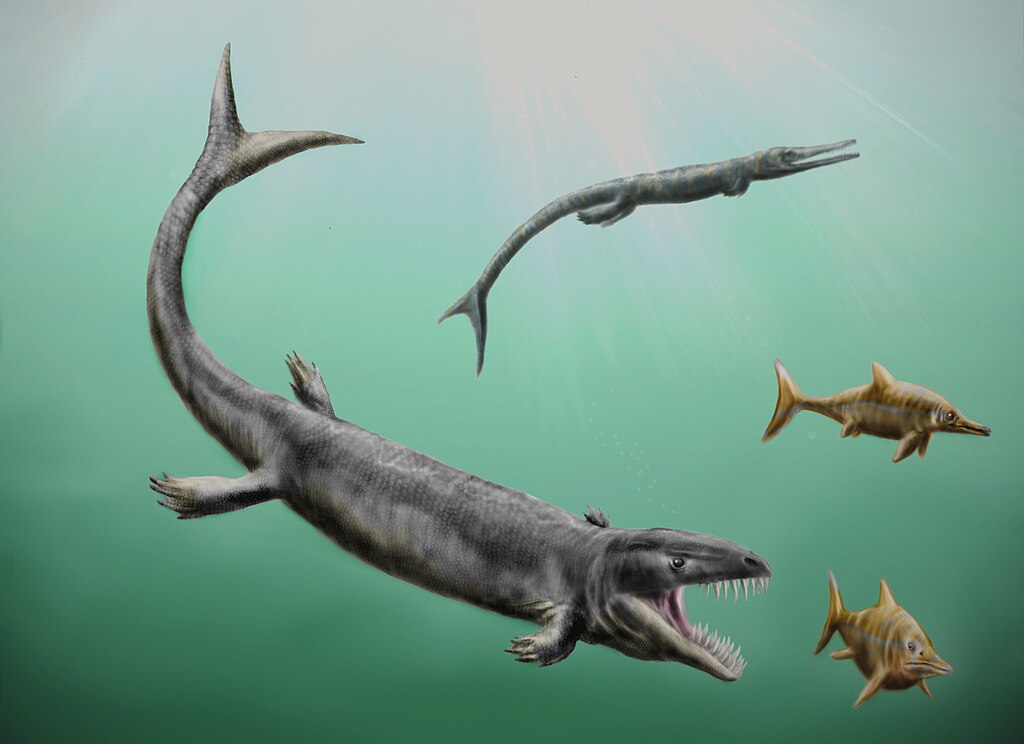

Rulers of Ancient Seas: Marine Reptiles

The aquatic realm of the Mesozoic era featured its spectacular reptilian giants that likely contributed to sea dragon mythology worldwide. Unlike dinosaurs and pterosaurs, groups like ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs were genuine reptiles that returned to marine environments, evolving streamlined bodies and flippers for efficient swimming. Ichthyosaurs, with their dolphin-like appearance and powerful jaws, embodied the swift and deadly aspect of sea monsters. Plesiosaurs, particularly the long-necked elasmosaurs, may have influenced tales of serpentine sea dragons with their snake-like necks and paddle-like limbs. Perhaps most dragon-like were the mosasaurs, massive marine lizards that reached lengths of up to 17 meters and possessed powerful jaws lined with conical teeth. Their remains, when discovered by ancient peoples living along coastlines, could easily have been interpreted as evidence of massive sea dragons. The geographic distribution of these marine reptile fossils corresponds remarkably well with coastal regions where sea dragon myths proliferated, suggesting a direct connection between paleontological discoveries and mythological development.

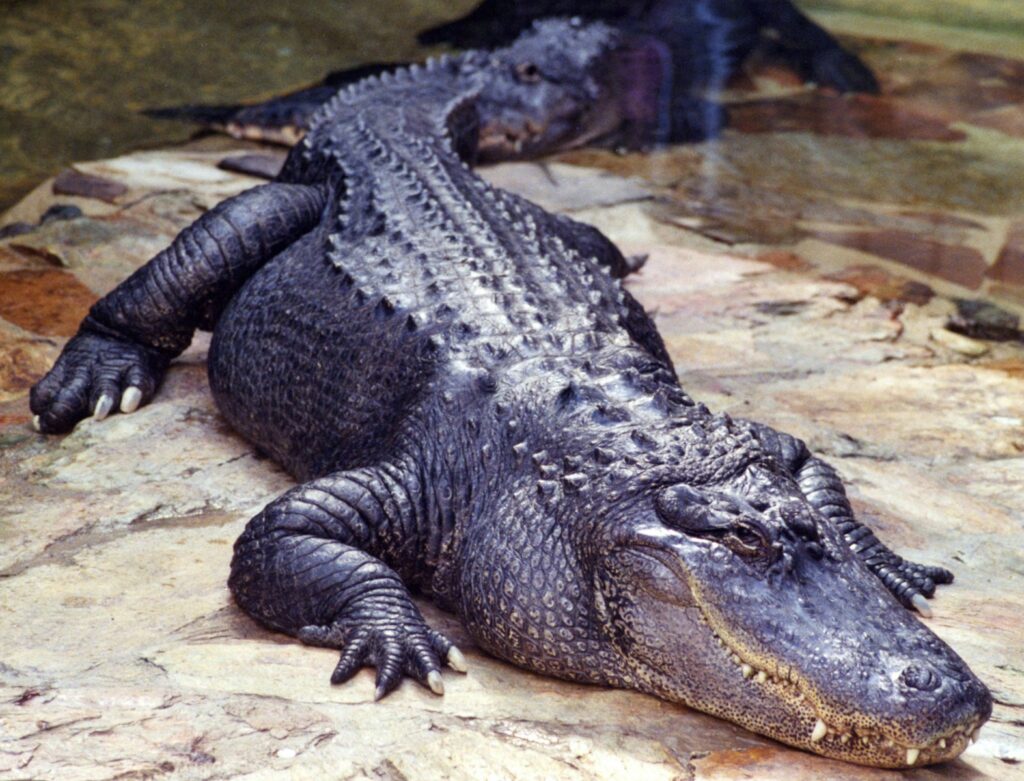

Crocodilians: Living Dragon Analogues

Among all reptilian groups, crocodilians perhaps represent the closest living analogues to mythical dragons, having retained much of their prehistoric appearance for over 200 million years. These formidable predators first appeared during the Late Triassic period and survived the mass extinction that claimed the non-avian dinosaurs, continuing their evolutionary journey into the present day. Ancient crocodilians like Deinosuchus and Sarcosuchus reached staggering sizes, with some specimens estimated at over 10 meters long, rivaling the dimensions often attributed to mythical dragons. Their armored bodies, powerful jaws capable of bone-crushing force, and ambush predator behavior all parallel traits commonly associated with dragons in folklore. The saltwater crocodile’s ability to launch itself partially out of water during attacks may have inspired tales of dragons emerging from lakes and rivers to capture prey. Furthermore, the worldwide distribution of crocodilians meant that human cultures across different continents encountered these living “dragons,” potentially explaining the remarkably similar dragon myths that emerged independently in geographically separated regions.

Megalania: Australia’s Dragon Monitor

The island continent of Australia hosted one of the most dragon-like reptiles of the more recent prehistoric past: Megalania prisca (now classified as Varanus priscus). This massive monitor lizard, which lived during the Pleistocene epoch until as recently as 50,000 years ago, may have reached lengths of 4-7 meters, making it the largest terrestrial lizard known to have existed. As a close relative of the modern Komodo dragon, Megalania would have possessed similar hunting strategies, including powerful jaws, serrated teeth, and possibly venomous saliva. Its imposing size and appearance would have made it a fearsome apex predator in prehistoric Australia, potentially encountering the first human inhabitants who arrived approximately 65,000 years ago. Indigenous Australian mythology contains numerous references to giant reptilian creatures that may represent cultural memories of encounters with Megalania. The relative recency of this species’ existence means it potentially played a direct role in shaping dragon myths in Oceania, where stories of massive lizards with venomous bites closely parallel the biological reality of this vanished monitor lizard.

Dragon Anatomy: Biological Realities vs. Mythological Embellishments

The physical characteristics attributed to dragons across world mythologies often reflect exaggerated or combined features of various prehistoric reptiles. The Western dragon’s four-legged stance with wings bears a striking resemblance to a hypothetical hybrid between dinosaurs and pterosaurs, while the Eastern dragon’s serpentine body echoes the form of long-necked marine reptiles. Scale patterns described in dragon lore mirror the osteoderms (bony deposits) found in crocodilian skin and certain dinosaur species, providing natural defense similar to the impenetrable hide attributed to mythical dragons. The fire-breathing capability, though biologically implausible, may have origins in observations of defensive mechanisms in certain animals, or could represent metaphorical descriptions of the deadly nature of encounters with large predatory reptiles. Dragon teeth in mythology—described as razor-sharp and sometimes venomous—parallel the dental adaptations of predatory dinosaurs and monitor lizards like Megalania. Even dragon claws, often depicted as capable of rending armor and flesh, find their prehistoric counterparts in the curved talons of dromaeosaurs (“raptor” dinosaurs) and the grasping claws of pterosaurs, demonstrating how biological realities informed even the most fantastical aspects of dragon mythology.

From Fossils to Folklore: The Archaeological Connection

Archaeological evidence suggests that fossil discoveries played a crucial role in the development of dragon mythology across ancient civilizations. In China, documented “dragon bones” from the 16th century BCE have been identified as dinosaur fossils, demonstrating that ancient peoples were actively collecting and interpreting these remains long before modern paleontology. Similarly, Greek and Roman natural philosophers, including Pliny the Elder, described massive bones unearthed throughout the Mediterranean region, attributing them to heroes and monsters from their mythological traditions. The remarkably similar dragon myths that emerged independently across cultures likely stem from similar human interpretations of fossil evidence. Particularly telling is the correlation between fossil-rich regions and areas with strongly developed dragon mythologies, such as the Gobi Desert in Mongolia and central China, the western United States, and parts of Europe where dinosaur remains are abundant. Ancient people, lacking scientific explanations for these massive bones, created narratives featuring scaled, reptilian monsters that matched the partial evidence before them, effectively making dragon myths an early form of paleontological interpretation filtered through cultural and religious frameworks.

Cultural Variations in Dragon Depictions: East vs. West

The striking differences between Eastern and Western dragon imagery may reflect regional variations in the prehistoric reptiles whose fossils inspired these myths. Western dragons typically appear as fire-breathing, winged quadrupeds with aggressive tendencies, potentially influenced by discoveries of large dinosaur remains combined with pterosaur fossils found throughout Europe and the Middle East. In contrast, Eastern dragons, particularly those from Chinese mythology, manifest as serpentine, often wingless creatures associated with water and benevolence, possibly reflecting the abundant long-necked marine reptile fossils found across East Asia. The Chinese dragon’s association with rainfall and fertility might connect to discoveries of these marine reptile remains during periods of drought, leading to cultural associations between the creatures and water. African dragon myths, featuring creatures like the Mokele-mbembe, often describe surviving dinosaur-like animals in remote regions, possibly influenced by both fossil discoveries and cultural memories of encounters with large crocodilians. These regional variations in dragon imagery demonstrate how different prehistoric reptile species, filtered through distinct cultural lenses, produced remarkably diverse yet recognizably related mythological traditions worldwide.

Dragons in Medieval Natural History

Medieval European naturalists and scholars treated dragons not as mythological creatures but as rare yet real animals, including them in serious zoological treatises alongside known species. Works like Konrad Gesner’s “Historia Animalium” (1551-1558) and Edward Topsell’s “The Historie of Serpents” (1608) presented detailed descriptions of dragons, often accompanied by illustrations that blend features of various reptiles with fantastical elements. These accounts frequently cited classical authorities like Pliny the Elder, who had himself documented reports of “dracones” from various regions. The medieval understanding of dragons shows remarkable parallels to actual prehistoric reptiles, often describing them as large, scaled creatures that laid eggs and possessed powerful jaws and sometimes wings. Medieval dragon specimens displayed in churches and noble collections have since been identified as manipulated crocodile or ray carcasses, or misidentified fossil remains of prehistoric marine and terrestrial reptiles. This pseudo-scientific treatment of dragons represents an intermediate stage between pure mythology and modern paleontology, where observations of fossil evidence were interpreted through a pre-scientific lens that still recognized the reptilian nature of these ancient creatures.

Modern Dragons: Komodo and Beyond

While ancient reptiles extinct millions of years ago inspired dragon myths, several modern reptile species perpetuate the dragon legacy through their appearance and behavior. The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), the world’s largest living lizard, represents perhaps the closest living equivalent to mythical dragons, growing up to 3 meters long and weighing over 150 kilograms. These formidable predators possess many dragon-like qualities: they have armored skin, powerful claws, serrated teeth, and hunt with a strategy involving venomous saliva that can cause fatal infections, reminiscent of the “poisonous breath” attributed to dragons in some legends. Other modern “dragons” include the Chinese crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus), whose scale pattern and semi-aquatic lifestyle parallel Asian dragon descriptions, and the magnificent flying dragons (Draco species) of Southeast Asia, which possess expandable rib membranes allowing them to glide between trees like their mythical namesakes. Even certain marine iguanas, with their ability to expel salt through their nostrils (creating a steam-like effect), have been compared to the “smoke-breathing” aspect of legendary dragons. These living reptiles provide a tangible connection to both prehistoric reptilian giants and the mythological creatures they inspired across human cultures.

The Science Behind Dragon Myths: Paleontology Meets Mythology

Modern paleontological science has validated many of the connections between prehistoric reptiles and dragon mythology theorized by cultural historians. In a fascinating 2016 study published in the Journal of Ethnobiology, researchers demonstrated strong correlations between fossil-rich regions in China and the geographic distribution of dragon myths, suggesting direct causation between fossil discoveries and mythological development. Similarly, paleontologist Adrienne Mayor’s groundbreaking work “The First Fossil Hunters” established compelling evidence that ancient Mediterranean cultures interpreted dinosaur and mammoth remains as belonging to creatures from their mythological traditions, including dragons. The science of taphonomy (how organisms decay and fossilize) explains why certain anatomical features of prehistoric reptiles might be emphasized in fossil remains, potentially influencing specific aspects of dragon imagery. For instance, the prominent head crests of many pterosaurs are preserved well and would be particularly striking to ancient fossil finders. Advances in comparative mythology using statistical analysis have further supported the hypothesis that dragon myths worldwide share a common origin in human interpretations of fossil evidence, demonstrating convergent mythological evolution in response to similar natural stimuli across different cultures.

Dragons in the Modern Imagination

The enduring fascination with dragons in contemporary culture owes much to their prehistoric reptilian origins, with popular media often drawing direct connections between dinosaurs and dragon imagery. Modern fantasy literature and film, from Tolkien’s Smaug to the dragons of “Game of Thrones,” frequently incorporate scientifically accurate reptilian features alongside traditional mythological elements, creating creatures that balance biological plausibility with fantasy. This trend extends to paleontologically-informed dragon designs in video games like “Monster Hunter,” where creatures often resemble specific dinosaur species with fantastical adaptations. The scientific understanding of prehistoric reptiles continues to influence how we conceptualize dragons, with new paleontological discoveries sometimes prompting revisions in popular dragon depictions. Recent findings about dinosaur coloration, feathering, and behavior have inspired more scientifically informed dragon portrayals in some media. Museums worldwide now capitalize on the connection between dinosaurs and dragons, with exhibits that explicitly address how fossil evidence influenced dragon mythology throughout human history. This modern synthesis of scientific understanding and mythological tradition demonstrates the ongoing dialogue between our knowledge of prehistoric reptiles and our cultural imagination, allowing dragons to evolve in our collective consciousness just as their reptilian ancestors evolved across millions of years of Earth’s history.

Conclusion

The remarkable parallels between prehistoric reptiles and dragon mythology reveal the profound impact these ancient creatures had on human culture long before formal paleontology emerged. From massive dinosaurs to soaring pterosaurs and serpentine marine reptiles, the fossil evidence of these prehistoric animals provided tangible foundations for dragon myths worldwide. As paleontological science advances, we gain a deeper understanding of both the magnificent reptiles that once ruled our planet and the psychological mechanisms through which early humans interpreted their remains. This prehistoric legacy continues today, with dragons maintaining their powerful grip on our collective imagination through literature, film, and art. The enduring popularity of these mythical creatures stands as a testament to the timeless fascination inspired by the actual reptilian giants that once dominated Earth’s ecosystems. In dragons, we find the perfect synthesis of scientific reality and human imagination—a bridge connecting our understanding of natural history with our capacity for mythological wonder.