For decades, the prevailing theory about dinosaur extinction has centered on a catastrophic asteroid impact approximately 66 million years ago. This event, known as the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction, wiped out approximately 75% of all species on Earth, including the non-avian dinosaurs that had dominated terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years. However, recent paleontological discoveries and ecological analyses have begun to challenge the simplicity of this narrative. Some researchers now propose that early mammals, often portrayed as inconsequential “bit players” during the Mesozoic Era, may have played a more significant role in dinosaur decline than previously thought. This article explores this fascinating hypothesis and examines the growing evidence that suggests our distant mammalian ancestors might have contributed meaningfully to dinosaur extinction through various ecological interactions long before the asteroid struck.

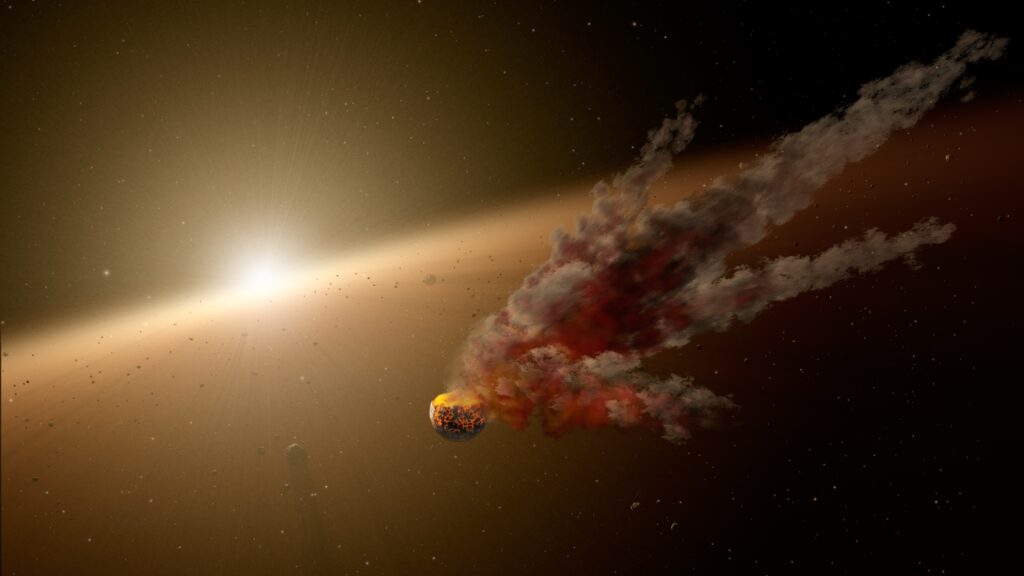

The Traditional Extinction Narrative

The asteroid impact theory has dominated scientific understanding of dinosaur extinction since the 1980s, when geologists discovered the massive Chicxulub crater in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. This 110-mile-wide impact structure provides compelling evidence for a catastrophic event precisely at the K-Pg boundary. The impact would have triggered tsunamis, wildfires, acid rain, and a global “impact winter” as dust and aerosols blocked sunlight for months or years. This sudden environmental devastation explains the abrupt disappearance of dinosaurs from the fossil record and has been supported by extensive geological evidence, including an iridium-rich layer at the K-Pg boundary worldwide. For most paleontologists, this dramatic scenario has served as the definitive explanation for dinosaur extinction, relegating other factors to secondary importance at most.

Challenging the Status Quo

Despite the compelling evidence for an asteroid impact, several paleontologists have begun questioning whether this single event truly tells the complete story of dinosaur extinction. Some fossil evidence suggests dinosaur diversity was already declining gradually in the late Cretaceous, potentially millions of years before the asteroid impact. Environmental change, including cooling temperatures, sea level fluctuations, and intense volcanic activity from the Deccan Traps in India, was already stressing dinosaur populations. Additionally, the pattern of extinction was not uniform across all dinosaur groups, with some lineages showing signs of decline well before the K-Pg boundary. These observations have led researchers to consider whether the asteroid delivered the final blow to already-vulnerable dinosaur populations that were facing multiple ecological challenges.

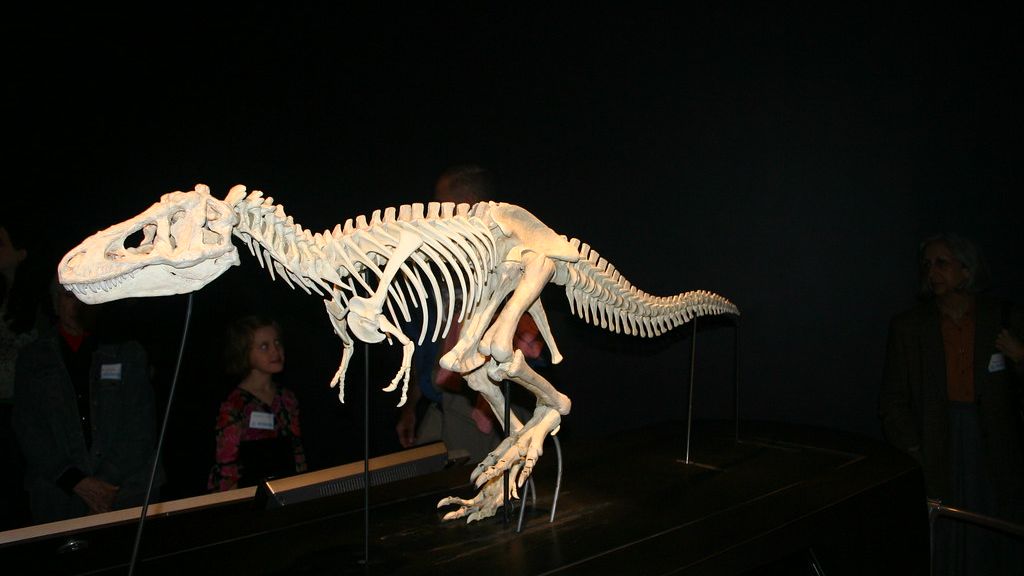

Early Mammals: Not Just Nocturnal Insectivores

The traditional view of Mesozoic mammals portrays them as small, shrew-like creatures scurrying between dinosaurs’ feet, primarily active at night, nd feeding on insects. However, fossil discoveries over the past two decades have dramatically revised this perception. We now know that Mesozoic mammals were far more diverse in form and ecological function than previously believed. Some grew to surprising sizes, with Repenomamus giganticus reaching dog-like proportions. Dietary diversity was also significant, with evidence of carnivory, omnivory, and herbivory among different mammal groups. Fossils have even revealed that some mammals like Repenomamus fed on small dinosaurs, as evidenced by dinosaur remains found in their stomach contents. This revised understanding of early mammals as ecologically varied creatures forms the foundation for reconsidering their potential influence on dinosaur populations.

Egg Predation and Dinosaur Vulnerability

One of the most significant ways early mammals may have impacted dinosaur populations was through egg predation. Dinosaurs, like modern reptiles and birds, laid eggs that remained vulnerable during incubation periods, sometimes lasting months for larger species. Recent studies of fossil mammals have revealed specializations for egg-eating in several lineages, including dental and cranial adaptations similar to modern egg-specialist predators. Computer modeling of dinosaur population dynamics suggests that even modest increases in egg predation rates could significantly impact population sustainability, especially for larger dinosaur species that matured slowly and had lower reproductive rates. This vulnerability would have been particularly pronounced if mammals were developing more sophisticated predation strategies or expanding their ecological niches during the late Cretaceous.

Competitive Advantages of Early Mammals

Mammals possessed several biological innovations that may have given them competitive advantages over dinosaurs in certain ecological contexts. Endothermy (warm-bloodedness) allowed mammals to maintain activity during cooler temperatures or at night when many dinosaurs may have been less active. Their specialized teeth enabled more efficient processing of a variety of foods, potentially allowing better nutrient extraction compared to the simpler dentition of many dinosaurs. Mammals’ higher metabolic rates, though requiring more frequent feeding, supported greater neural development and potentially more complex behavioral adaptations. Additionally, live birth and maternal care meant mammalian young developed in protected environments and received extended parental investment, potentially reducing juvenile mortality compared to many dinosaur species. These advantages wouldn’t have made mammals superior to dinosaurs in all contexts, but may have given them competitive edges in specific ecological niches.

The Fossil Evidence for Mammalian Impact

Paleontological discoveries provide tantalizing evidence for mammal-dinosaur interactions that could have influenced dinosaur decline. Multituberculates, a successful group of rodent-like mammals, show dental adaptations suggesting they competed with certain dinosaurs for plant resources during the Late Cretaceous. Fossilized stomach contents from Mesozoic mammals occasionally include dinosaur remains, proving that direct predation occurred. Some fossil sites show evidence of mammalian gnawing marks on dinosaur eggs and bones, particularly at nesting sites. The timing of mammalian diversification also correlates intriguingly with changes in dinosaur communities, with mammals expanding into new ecological niches as certain dinosaur groups declined. While correlation doesn’t prove causation, these fossil finds collectively suggest early mammals were actively interacting with dinosaur populations in potentially significant ways.

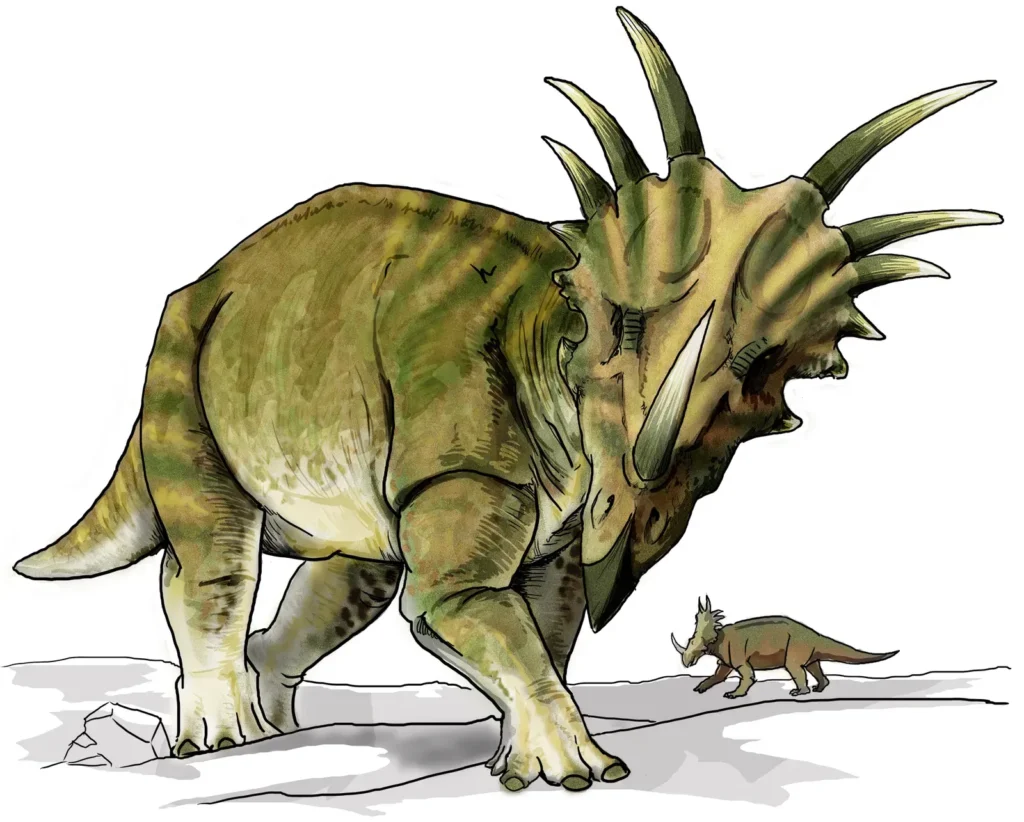

Niche Competition and Resource Partitioning

Ecological modeling suggests that increasing competition between certain dinosaur groups and mammals for critical resources may have stressed dinosaur populations. Mammals and small-bodied dinosaurs likely competed for similar food sources, particularly seeds, fruits, insects, and small vertebrates. As mammalian diversity increased during the Late Cretaceous, this competition potentially intensified. Some research indicates that dinosaurs and mammals were undergoing significant ecological “niche partitioning” during this period, suggesting active competition was driving evolutionary adaptations in both groups. Fossil evidence from feeding adaptations shows mammals were evolving more specialized dentition for processing specific foods, potentially allowing them to extract more nutrition from the same resources dinosaurs were using. While dinosaurs still dominated in terms of overall biomass, these competitive interactions could have gradually shifted the ecological balance.

Environmental Changes Favoring Mammals

The Late Cretaceous was a period of significant environmental fluctuation that may have advantaged mammals over dinosaurs in certain contexts. Global cooling trends would have benefited endothermic mammals that could maintain activity in cooler temperatures compared to potentially more temperature-dependent dinosaurs. Changing vegetation patterns, including the spread of flowering plants (angiosperms), created new ecological opportunities that mammals could exploit with their more versatile dentition. Sea level fluctuations fragmented habitats, potentially isolating dinosaur populations while more mobile mammals could navigate changing landscapes more effectively. These environmental shifts didn’t necessarily harm dinosaurs directly, but they may have created conditions where mammals could compete more effectively in certain habitats, gradually expanding their ecological influence.

Disease Vectors and Parasitism

An often-overlooked potential interaction between early mammals and dinosaurs involves disease transmission and parasitism. Modern mammals serve as reservoirs and vectors for numerous diseases affecting other animals, and it’s plausible that Mesozoic mammals played similar roles. Some researchers have proposed that as mammals diversified and increased interactions with dinosaurs, they may have exposed dinosaur populations to novel pathogens. Mammalian parasites could have jumped to dinosaur hosts, potentially causing health impacts in populations with no evolutionary history of resistance. While direct evidence for such disease transmission is difficult to find in the fossil record, theoretical models suggest it represents a plausible mechanism for mammals to impact dinosaur health and population viability. The growing proximity of mammals to dinosaur habitats, particularly nesting sites, would have increased opportunities for such transmission events.

Synergistic Effects with Environmental Stressors

The most compelling argument for mammalian influence on dinosaur extinction may not be that mammals alone caused dinosaur decline, but rather that mammalian pressures acted synergistically with other environmental stressors. Volcanic activity from the Deccan Traps was already altering climates and atmospheres in the Late Cretaceous. Sea level changes were restructuring coastal habitats. Global cooling was likely affecting biological processes for many dinosaur species. Against this backdrop of environmental challenges, even relatively modest additional pressures from mammalian egg predation, resource competition, or disease transmission could have had amplified effects on dinosaur population viability. Complex systems theory suggests that multiple stressors often produce effects greater than the sum of their impacts, potentially creating extinction vulnerabilities that no single factor would trigger alone.

Contemporary Scientific Debates

The hypothesis that mammals contributed meaningfully to dinosaur extinction remains contentious within paleontological circles. Critics point to the relatively small size and presumed ecological insignificance of most Mesozoic mammals compared to dinosaurs. They argue that the fossil record shows dinosaurs remained dominant and diverse until the very end of the Cretaceous, suggesting minimal mammalian impact. Proponents counter that ecological influence doesn’t necessarily correlate with body size or biomass dominance, pointing to how modern invasive rodents can devastate island ecosystems despite their small size. Some researchers take middle positions, suggesting mammals may have contributed to the decline of specific dinosaur groups or in particular habitats, while having minimal impact on others. This ongoing debate reflects the challenge of reconstructing complex ecological interactions from an incomplete fossil record spanning millions of years.

Research Challenges and Future Directions

Testing hypotheses about mammal-dinosaur interactions presents significant research challenges due to the fragmentary nature of the fossil record. Future research will likely focus on developing more sophisticated ecological models incorporating variables like predation rates, competition coefficients, and population dynamics to test theoretical scenarios. More detailed isotopic analyses of fossil teeth might reveal changing patterns of resource use and potential competition between mammals and dinosaurs. Expanded efforts to find and document Late Cretaceous fossil localities globally could provide better temporal and geographic resolution of extinction patterns. Paleontologists are also exploring techniques from taphonomy (the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized) to better detect evidence of mammalian predation or scavenging on dinosaur remains. These multidisciplinary approaches may eventually provide clearer evidence for or against significant mammalian influence on dinosaur extinction.

Lessons for Understanding Modern Extinctions

The debate about mammalian influences on dinosaur extinction holds relevance for understanding modern biodiversity crises. Even if early mammals played only a minor role in dinosaur decline, the possibility that small, seemingly insignificant species could impact dominant ecosystem members through complex ecological interactions parallels modern conservation concerns. Today’s biodiversity crisis involves countless subtle ecological disruptions occurring simultaneously with more obvious environmental changes. The paleontological debate reminds us that extinction rarely has single, simple causes, but emerges from complex interactions between multiple factors, including competition, predation, environmental change, and random events. Understanding how Earth’s previous dominant vertebrates declined may provide insights into the vulnerabilities of today’s ecosystems and the potentially unexpected ways that species interactions can drive ecological transformation.

Conclusion

While the asteroid impact at the end of the Cretaceous undoubtedly delivered a catastrophic blow to Earth’s ecosystems, the emerging evidence suggests dinosaur extinction may have had a more complex backstory involving our mammalian ancestors. Early mammals likely existed in a dynamic ecological relationship with dinosaurs, potentially exerting selective pressures through egg predation, resource competition, and other interactions that may have contributed to dinosaur vulnerabilities. Rather than seeing mammals as merely beneficiaries of dinosaur extinction, we might more accurately view them as active participants in a complex ecological drama that unfolded over millions of years. The ultimate extinction of non-avian dinosaurs probably resulted from a “perfect storm” of factors: long-term environmental changes, increasing mammalian pressures, and finally, a devastating asteroid impact. This multifaceted understanding of dinosaur extinction reminds us that even Earth’s most dominant species exist within complex ecological webs that shape their evolutionary fates.