The Late Cretaceous period, spanning from approximately 100 to 66 million years ago, witnessed Earth’s oceans teeming with some of the most formidable marine predators to ever exist. As dinosaurs dominated the land, equally impressive giants ruled the prehistoric seas. These ancient marine hunters evolved remarkable adaptations that made them perfectly suited for their aquatic domains, creating complex ecosystems and food chains in oceans far different from those we know today. From massive reptiles with paddle-like limbs to enormous fish with bone-crushing jaws, the Late Cretaceous seas were truly a realm of giants where survival meant becoming an efficient predator or falling prey to one.

Mosasaurs: The Ruling Reptiles

Mosasaurs emerged as the undisputed apex predators of the Late Cretaceous seas, evolving from terrestrial lizards into massive marine reptiles that could reach lengths of over 50 feet. These creatures possessed powerful jaws lined with conical teeth perfect for seizing and holding struggling prey, including fish, ammonites, and even other marine reptiles. Unlike their land-dwelling relatives, mosasaurs developed paddle-like limbs and a long, flexible body ending in a downward-bending tail fluke that provided tremendous propulsion through water. Species diversity within the mosasaur family was remarkable, with forms ranging from the enormous Tylosaurus to more modestly-sized but equally fearsome hunters like Platecarpus. Their dominance was so complete that paleontologists often refer to the Late Cretaceous as the “Age of Mosasaurs” when discussing marine environments.

Tylosaurus: The Tyrant of the Deep

Among mosasaurs, Tylosaurus stood out as a particularly formidable predator, reaching lengths of up to 50 feet and weighing several tons. This massive reptile possessed a distinctive pointed snout projection called a rostrum, which likely served both as a ramming weapon and as a hydrodynamic feature that reduced water resistance during high-speed pursuits. Fossil evidence has revealed the contents of Tylosaurus’ stomachs, demonstrating that these monsters consumed virtually anything they could catch, including fish, sharks, birds, and even other mosasaurs. Their powerful jaws were equipped with two rows of teeth in the upper palate, creating a deadly trap that prey could not escape once seized. Tylosaurus’s reign extended across what is now the Western Interior Seaway that divided North America, with numerous fossils discovered in Kansas, South Dakota, and Manitoba revealing how widespread and successful these predators were during their 10-million-year dominance.

Plesiosaurs: The Long-Necked Hunters

Plesiosaurs represent one of the most distinctive groups of marine reptiles, characterized by their four powerful flippers and body designs that came in two primary configurations: the long-necked, small-headed elasmosaurids and the short-necked, large-headed pliosaurs. During the Late Cretaceous, elasmosaurids like Elasmosaurus reached incredible proportions, with necks containing more than 70 vertebrae and stretching up to 25 feet long on a body measuring 46 feet in total length. These remarkable adaptations allowed them to sneak their heads into schools of fish or to reach prey hiding among reef structures without alerting them with their larger body. Their hunting style likely involved a combination of stealth and sudden strikes, using their long necks to approach prey from unexpected angles. While superficially resembling the popular conception of the “Loch Ness Monster,” plesiosaurs were highly specialized marine predators that had evolved over millions of years to perfect their unique body plan and hunting strategy.

Kronosaurus: The Short-Necked Leviathan

Unlike their long-necked plesiosaur relatives, pliosaurs like Kronosaurus featured a more compact design with massive heads, short necks, and barrel-shaped bodies powering four enormous flippers. Kronosaurus, named after the titan Kronos from Greek mythology, reached lengths of approximately 30-33 feet with a skull measuring nearly 9 feet long, among the largest of any predator that ever lived. This enormous head housed jaws lined with conical teeth measuring up to 11 inches in length, creating a bite force that could easily crush through the shells of giant sea turtles and the bones of other marine reptiles. Kronosaurus’s hunting strategy likely involved explosive bursts of speed to ambush prey, using its powerful flippers to achieve surprising acceleration despite its massive size. Evidence suggests that these apex predators occupied the highest trophic levels in their ecosystems, preying upon virtually anything that shared their waters, including other large marine reptiles.

Xiphactinus: The Bulldog of the Cretaceous Sea

Not all Late Cretaceous marine predators were reptiles – the enormous bony fish Xiphactinus represents one of the most fearsome non-reptilian hunters of this era. Growing up to 20 feet in length, this monstrous fish possessed a bulldog-like face with massive fangs jutting from its jaws, earning it the nickname “the bulldog fish” among paleontologists. One of the most famous Xiphactinus fossils, discovered in Kansas, contains the perfectly preserved remains of another large fish inside its body cavity, suggesting this individual died shortly after consuming its last meal whole. Xiphactinus belonged to the extinct group Ichthyodectidae and was related to modern teleost fish, showing how conventional fish designs could also evolve into apex predator forms during this period. Their powerful, streamlined bodies allowed them to reach high speeds, likely making them ambush predators that relied on quick bursts to overtake prey rather than sustained pursuits.

Cretoxyrhina: The Cretaceous Great White

Known as the “Ginsu shark” due to its serrated, razor-sharp teeth, Cretoxyrhina mantelli was a massive lamniform shark that grew to approximately 25 feet in length. This ancient predator bore remarkable similarities to the modern great white shark in body form and hunting strategy, though it belonged to a different family and grew significantly larger than today’s great whites. Exceptionally preserved fossils have revealed not just teeth but cartilaginous structures of the skeleton, skin impressions, and even stomach contents, providing paleontologists with a detailed understanding of this prehistoric shark’s anatomy and ecology. Cretoxyrhina’s menu included mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, large fish, and even pterosaurs that may have skimmed too close to the water’s surface. The shark’s hunting technique likely involved explosive ambush attacks from below, similar to those employed by modern great whites when hunting seals, making it one of the most versatile and successful predators in the Late Cretaceous ecosystem.

Archelon: The Turtle Titan

While not primarily a predator, Archelon ischyros deserves mention as the largest sea turtle that ever lived, reaching lengths of up to 15 feet with a shell span of 13 feet. This enormous chelonian inhabited the Western Interior Seaway during the Late Cretaceous, evolving defenses that allowed it to survive in waters dominated by mosasaurs and other fearsome predators. Unlike modern sea turtles with solid shells, Archelon possessed a lighter skeletal structure with a leathery carapace stretched over a frame of supportive bones, reducing weight while maintaining protection. Its powerful jaws were adapted for crushing the shells of ammonites, squid, and various crustaceans that formed the bulk of its diet, making it an important secondary consumer in the marine food web. Despite its impressive size and specialized feeding adaptations, fossil evidence suggests that Archelon still fell prey to larger predators like Tylosaurus, as evidenced by bite marks found on some Archelon specimens.

Hesperornis: The Toothed Diving Bird

The Late Cretaceous seas featured unexpected predators in the form of specialized diving birds like Hesperornis, which grew to nearly 6 feet in length and possessed tiny, vestigial wings that rendered it flightless but remarkably adapted for underwater pursuits. Unlike modern birds, Hesperornis retained sharp, recurved teeth in its beak, a primitive characteristic inherited from its dinosaurian ancestors that proved perfectly suited for catching slippery fish. Their legs were positioned far back on their bodies, similar to modern loons but even more extremely adapted for powerful swimming strokes, making them exceptional underwater hunters but awkward on land. Fossilized stomach contents reveal that Hesperornis primarily fed on fish, using its tooth-lined jaws to secure prey after high-speed underwater chases. These specialized avian predators represent an important example of convergent evolution with modern diving birds like penguins, though they followed a completely different evolutionary pathway to achieve their similar lifestyle.

Enchodus: The “Saber-Toothed Herring”

Enchodus was a genus of predatory fish that grew up to 4-5 feet in length and possessed distinctive, elongated fangs in its upper jaw that earned it the nickname “saber-toothed herring” (although it was not closely related to modern herrings). These impressive teeth, some reaching several inches in length, made Enchodus an effective midsize predator capable of impaling smaller fish with precision strikes. Fossil evidence shows that Enchodus was extraordinarily successful, with various species found in marine deposits worldwide and spanning from the early Cretaceous until the end of the period. Despite its fearsome dentition, Enchodus itself often fell prey to larger hunters, with fossils frequently showing evidence of predation by sharks, larger bony fish like Xiphactinus, and marine reptiles. The abundance of Enchodus fossils in Late Cretaceous marine deposits indicates these fish represented an important middle link in the food chain, transferring energy from smaller prey to the apex predators that dominated these ancient seas.

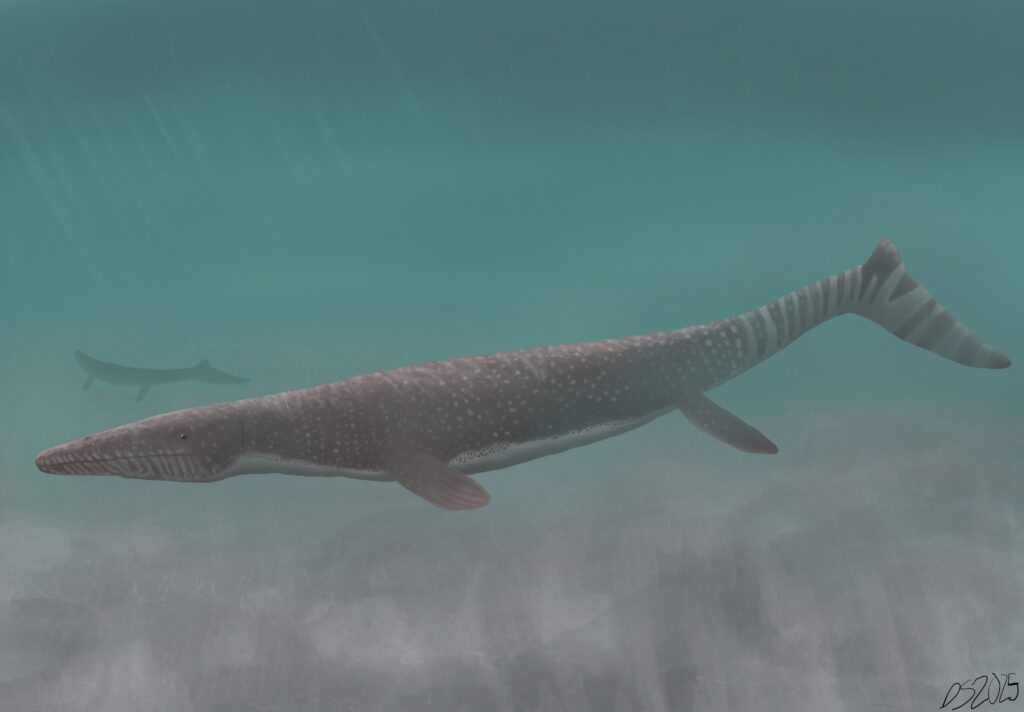

Halisaurus: The Coastal Mosasaur

Among mosasaurs, Halisaurus represents a more modestly sized genus that typically reached lengths of 10-13 feet, significantly smaller than giants like Tylosaurus but still formidable predators in coastal environments. Their more slender build and proportionally smaller heads suggest these mosasaurs occupied a different ecological niche than their larger relatives, potentially focusing on smaller prey in shallower waters. Fossil remains of Halisaurus have been found on multiple continents, indicating a widespread distribution during the Late Cretaceous and suggesting these animals were highly adaptable to various marine environments. Their dentition featured more uniform, conical teeth rather than the specialized cutting or crushing teeth seen in some other mosasaur genera, indicating a generalist feeding strategy that likely included fish, squid, and smaller marine reptiles. Halisaurus represents an important example of how mosasaurs diversified to fill multiple predatory niches within Late Cretaceous marine ecosystems, from shallow coastal hunters to deep-diving offshore specialists.

Protostega: The Second-Largest Sea Turtle

Slightly smaller than Archelon but still enormous by modern standards, Protostega gigas was the second-largest sea turtle known to science, with a shell span reaching approximately 10 feet across. Like its larger relative, Protostega featured a reduced, leathery shell that provided some protection while maintaining the buoyancy and flexibility needed for life in the dangerous Late Cretaceous seas. Anatomical studies suggest that despite its impressive size, Protostega was likely capable of relatively fast swimming, with powerful front flippers that provided both propulsion and maneuverability when pursuing prey or evading larger predators. Their diet consisted primarily of jellyfish, squid, and other soft-bodied creatures that could be captured and processed with their specialized beaks. Fossil evidence indicates that juvenile Protostega were significantly more vulnerable to predation than adults, with smaller individuals frequently showing evidence of attack by sharks and other predators, suggesting these turtles experienced high mortality rates before reaching their impressive adult dimensions.

The Western Interior Seaway: Predator Hotspot

During the Late Cretaceous, North America was divided by the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow epicontinental sea that stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean, creating one of the richest ecosystems for marine predators in Earth’s history. This warm, relatively shallow body of water, typically only a few hundred feet deep across much of its extent, created ideal conditions for a stunning diversity of marine life, including the full range of predators discussed in this article. The seaway’s geography created various environments within a single connected system, from coastal shallows to deeper central channels, allowing for specialized predators to evolve for each habitat type. Fossil beds in locations like Kansas, South Dakota, and Manitoba have yielded extraordinarily well-preserved specimens that have shaped our understanding of Late Cretaceous marine ecosystems. The high concentration of predators in this region suggests an incredibly productive ecosystem that supported multiple trophic levels, from tiny plankton through various filter-feeders and smaller predatory fish, all the way up to the massive apex predators like Tylosaurus and Cretoxyrhina.

Extinction and Legacy

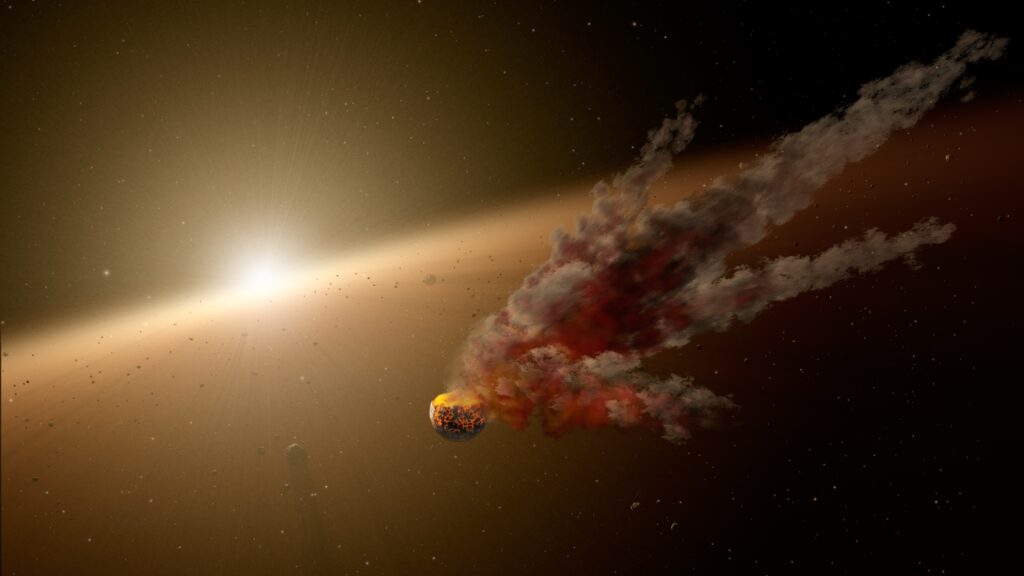

The remarkable diversity of marine predators that thrived during the Late Cretaceous came to an abrupt end approximately 66 million years ago when the Chicxulub asteroid impact triggered the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction event. This catastrophic occurrence eliminated approximately 75% of all species on Earth, including all marine reptiles exceeding 1 meter in length and the majority of large predatory fish. The extinction created evolutionary opportunities for survivors, with mammals eventually taking to the seas to evolve into whales and dolphins, while sharks diversified to fill many of the predatory niches left vacant. Modern marine ecosystems still bear the signature of this ancient catastrophe and subsequent evolutionary radiation, with today’s ocean predators being the distant beneficiaries of the ecological reset that occurred at the end of the Cretaceous. The giant predators of the Late Cretaceous seas represent an important chapter in Earth’s evolutionary history, demonstrating alternative approaches to the apex predator role that differ markedly from the mammals and sharks that would eventually come to dominate the world’s oceans after their extinction.

Conclusion

The Late Cretaceous oceans represented one of the most fearsome predator-dominated ecosystems in Earth’s history. From the massive mosasaurs that ruled as apex predators to specialized hunters occupying various ecological niches, these ancient seas were arenas of evolutionary innovation where multiple lineages independently developed impressive adaptations for marine predation. The diversity of hunting strategies, body plans, and ecological roles demonstrates the incredible evolutionary plasticity that produced such an assemblage of fearsome hunters. When we look at modern oceans, we see only a shadow of this prehistoric predator diversity, a reminder that Earth’s history contains chapters where life took dramatically different paths than those we observe today. The giant predators of the Late Cretaceous seas stand as testament to evolution’s capacity to produce extraordinary adaptations when time, opportunity, and ecological pressures align.