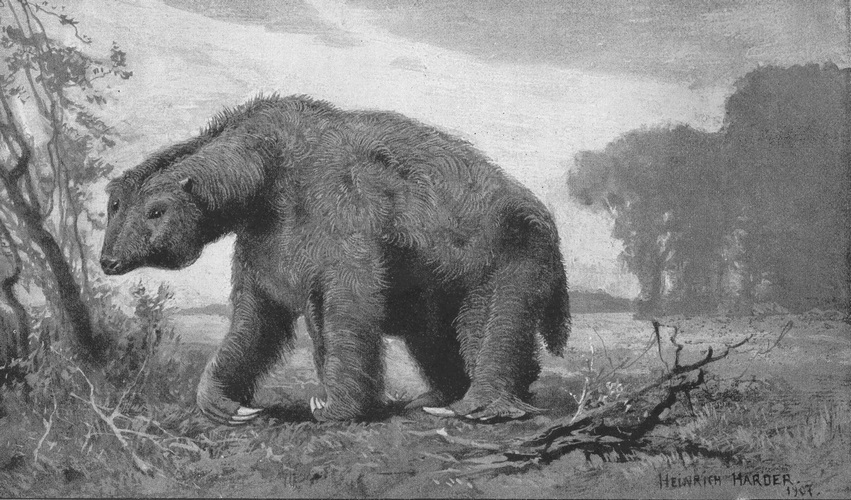

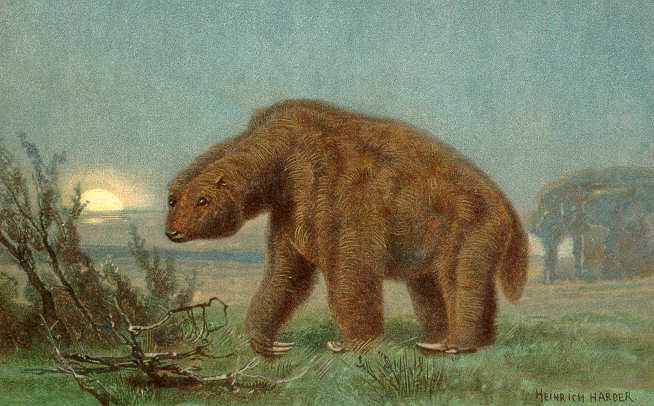

North America was once home to massive beasts that would seem alien to us today. Among the most fascinating were the giant ground sloths—enormous relatives of today’s tree-dwelling sloths that walked on all fours across the continent. These remarkable creatures, some standing up to 20 feet tall when rearing on their hind legs, inhabited North America for millions of years before disappearing roughly 10,000 years ago. Their story represents one of the most intriguing chapters in the continent’s prehistoric past, offering insights into ancient ecosystems and the dramatic environmental changes that shaped our modern world.

The Origins of Giant Ground Sloths

Giant ground sloths evolved in South America approximately 35 million years ago during the late Eocene epoch. Their evolutionary success story began in isolation, as South America existed as an island continent for much of the Cenozoic era. This geographic separation allowed for the development of unique mammalian species found nowhere else on Earth. The sloths diversified into numerous species, with some branches of the family tree developing into the massive ground-dwelling varieties. When the Isthmus of Panama formed around 3 million years ago, connecting North and South America, these impressive mammals were among the southern species that expanded northward in what scientists call the Great American Interchange. This migration event reshaped the faunal composition of both continents, with ground sloths becoming one of the most successful southerners to colonize the northern landmass.

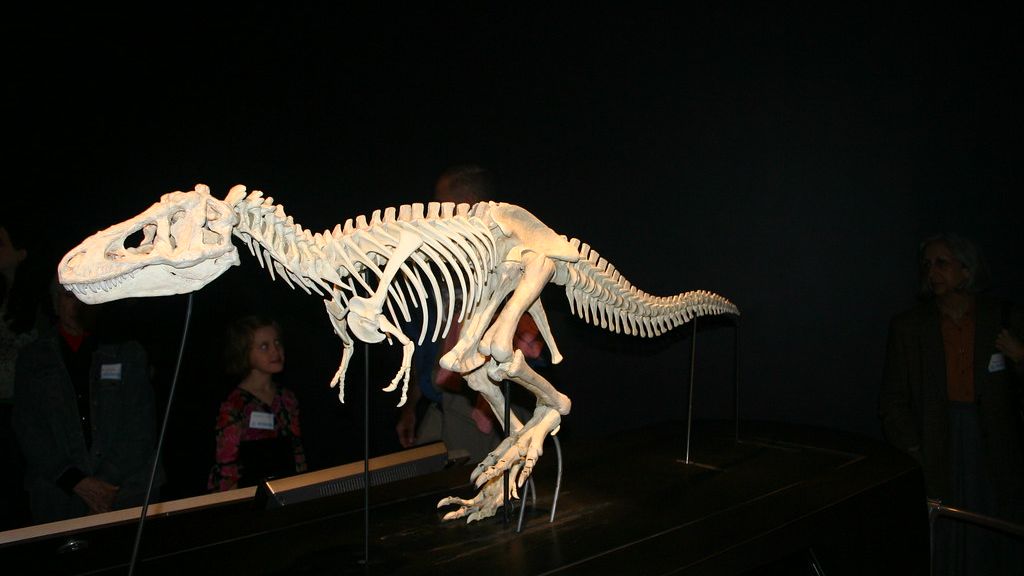

Meet Megalonyx: Jefferson’s Ground Sloth

One of North America’s most widespread giant ground sloths was Megalonyx jeffersonii, named in honor of Thomas Jefferson. Before becoming the third president of the United States, Jefferson had a deep interest in paleontology and natural history. In 1797, he presented what he believed were the remains of an enormous lion to the American Philosophical Society based on fossils found in a West Virginia cave. These bones were later correctly identified as belonging to a previously unknown species of giant ground sloth. Megalonyx grew to about 10 feet in length and weighed around 1,000 pounds—significantly larger than any modern sloth species. These creatures possessed powerful forearms equipped with large, curved claws that were likely used for pulling down branches, digging for roots, and possibly for defense against predators. Their remains have been discovered across much of the eastern and central United States, indicating they thrived in diverse habitats throughout the region.

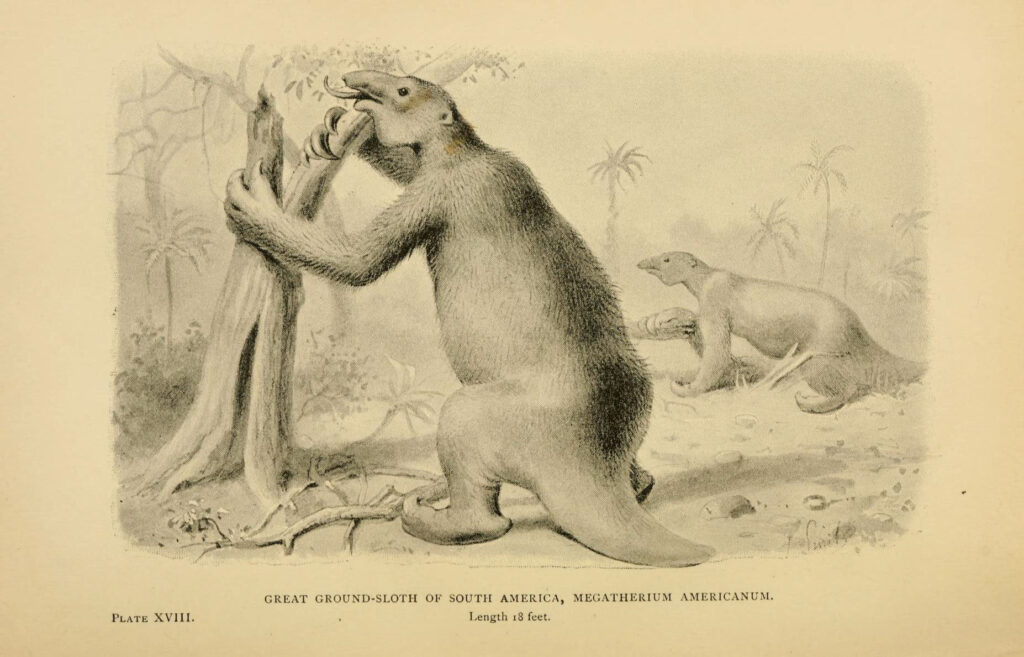

Eremotherium: The Coastal Giant

Among the most massive ground sloths to inhabit North America was Eremotherium laurillardi, a true heavyweight of the Pleistocene epoch. These enormous creatures could reach lengths of up to 20 feet and may have weighed more than 3 tons, comparable to a modern elephant. Unlike some other ground sloth species, Eremotherium appears to have preferred warmer coastal environments, with fossil remains concentrated along the southeastern United States from Florida to Texas. These giants had relatively smaller claws compared to other ground sloths, suggesting different feeding adaptations. Paleontologists believe Eremotherium was primarily a browser, using its height advantage to reach vegetation inaccessible to other herbivores. The coastal distribution of this species indicates they may have also enjoyed consuming saltwater plants or seaweed, adding an interesting dimension to their ecological role. Their substantial size likely protected them from most predators, though young individuals would have been vulnerable to the large cats and dire wolves of the period.

Nothrotheriops: The Shasta Ground Sloth

The Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops shastensis) represents one of the best-understood giant sloth species thanks to exceptionally preserved remains found in dry caves throughout the southwestern United States. Smaller than some of its relatives but still impressive by modern standards, Nothrotheriops measured about 9 feet in length and weighed roughly 550 pounds. Their remains have been discovered in remarkably well-preserved condition, sometimes including fur, skin, and even dung, offering scientists unprecedented insights into their biology. Analysis of their dung deposits, known as coprolites, has revealed that their diet consisted primarily of desert plants, including yucca, agave, and Joshua tree matter. The Shasta ground sloth appears to have been particularly well-adapted to arid environments, thriving in regions that today comprise Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and southern California. Some specimens are so well-preserved that scientists have recovered ancient DNA fragments, bringing us tantalizingly close to understanding their genetic makeup.

Physical Adaptations and Capabilities

Giant ground sloths possessed several remarkable physical adaptations that helped them thrive in diverse environments across North America. Their skeletal structure showed a unique combination of features that allowed them to both walk on all fours and rise on their hind legs to reach high vegetation. The vertebrae in their lower backs, pelvises, and tails were massively built to support their weight when standing upright, effectively functioning as a tripod with their sturdy tail forming the third point of support. Their front limbs featured enormous claws that curled inward when not in use, causing them to walk on the knuckles or sides of their forefeet, similar to the locomotion style seen in modern anteaters. Most species had thick, tough hides that likely contained embedded bony nodules called osteodermsprotectingst predators. Their teeth were simple peg-like structures without enamel, continuously growing throughout their lives and self-sharpening as they chewed tough plant material. These physical characteristics made giant ground sloths a highly specialized mammal, unlike anything alive today.

Dietary Habits and Feeding Behaviors

Ground sloths were exclusively herbivorous, but their specific dietary preferences varied among species and habitats. Their feeding ecology can be partially reconstructed through multiple lines of evidence, including tooth wear patterns, the structure of their jaws, fossilized dung, and isotope analysis of their remains. Most North American species appear to have been browsers rather than grazers, preferring leaves, twigs, fruits, and other plant materials from trees and shrubs instead of grasses. Their powerful forelimbs and claws served as effective tools for pulling down branches or digging up roots, while their ability to rear up on hind legs expanded their feeding range substantially. The preserved dung of Nothrotheriops has revealed that they consumed desert plants high in fiber and low in nutritional value, suggesting they had specialized digestive systems with slow metabolisms similar to modern sloths. This efficient processing of low-quality food would have allowed them to thrive in environments where other large herbivores might struggle. Some species may have played crucial ecological roles as seed dispersers for large-fruited plants, potentially explaining why certain plant species today appear to have evolved fruits seemingly designed for now-extinct megafauna.

Social Structure and Behavior

While behavioral aspects are challenging to determine from fossils alone, scientists have developed theories about giant ground sloth social structures based on comparative studies with modern mammals of similar size and ecological roles. Most evidence suggests these animals were likely solitary or semi-social, possibly coming together only during breeding seasons or when resources were concentrated. Their massive size would have made sustaining large groups difficult in most environments, as feeding so many individuals would quickly deplete local vegetation. The lack of sexual dimorphism (major size differences between males and females) in most species suggests they probably didn’t maintain harems or engage in intense male competition for mates like some modern herbivores. Their slow metabolism and movement patterns indicate they were likely not territorial in the traditional sense, instead ranging widely across landscapes in search of food. Young ground sloths probably remained with their mothers for extended periods, as the combination of slow growth rates and the need to learn specialized feeding behaviors would have necessitated prolonged parental care. Their behavioral patterns were likely characterized by deliberate movements and energy conservation strategies rather than the speed and agility seen in many modern mammals.

Interaction with Early Humans

One of the most fascinating aspects of giant ground sloth history is their temporal overlap with the earliest human inhabitants of North America. Archaeological evidence indicates that Paleoindian populations encountered these massive beasts as they spread across the continent. Several sites throughout the United States have yielded tantalizing evidence of human-sloth interaction, including a few locations where sloth bones bear what appear to be cut marks from stone tools. At White Sands National Park in New Mexico, researchers have documented remarkable fossil footprints showing what may be human hunters stalking a giant ground sloth, with human footprints found directly inside the larger sloth tracks in a pattern consistent with predatory behavior. Cave paintings in South America depict giant ground sloths, though similar artistic evidence has yet to be conclusively identified in North America. The timing of the arrival of humans in the Americas roughly coincides with the disappearance of these animals, fueling ongoing debates about whether human hunting played a significant role in their eventual extinction. These interactions represent a brief but significant moment when our ancestors shared landscapes with these now-vanished giants.

Surviving in the Ice Age

Ground sloths demonstrated remarkable adaptability by surviving through multiple glacial cycles during the Pleistocene epoch, commonly known as the Ice Age. While they generally preferred warmer environments, different species adapted to various climatic conditions across North America. Their ability to process low-quality plant materials allowed them to persist even when changing climates altered vegetation patterns. During glacial maxima, when ice sheets covered northern regions, southern populations likely served as refugia, with species ranges expanding northward during warmer interglacial periods. Fossil evidence suggests some species developed thicker fur in northern regions, with the Shasta ground sloth exhibiting a shaggy coat based on preserved hair samples from cave deposits. Their slow metabolisms would have been advantageous during periods of resource scarcity, requiring less food than similarly sized mammals with higher energy demands. The tremendous size of species like Eremotherium and Megalonyx also provided thermal advantages, as larger bodies lose heat more slowly relative to their volume—a principle known as Bergmann’s rule. This suite of adaptations allowed these remarkable creatures to persist through dramatic climate oscillations that drove many other species to extinction long before humans arrived on the continent.

The Mystery of Their Extinction

The disappearance of giant ground sloths roughly 10,000 years ago remains one of paleontology’s most debated topics. Their extinction occurred during a period of significant environmental and cultural change in North America, making it difficult to isolate a single cause. The end of the Pleistocene brought dramatic climate warming and vegetation changes as the Ice Age concluded, potentially disrupting ecosystems that these specialized herbivores depended upon. Simultaneously, human populations were expanding across the continent, armed with sophisticated hunting technologies. This convergence of factors has led to two predominant hypotheses: the climate change model and the overkill hypothesis. Many scientists now favor a synergistic explanation, suggesting that climate-stressed populations became more vulnerable to human predation, creating a “one-two punch” that these animals couldn’t survive. The timing of extinctions appears to vary by region, with some evidence suggesting ground sloths persisted in isolated areas like the Caribbean islands until perhaps 4,500 years ago—well into the period of advanced human civilizations in other parts of the world. The loss of these ecosystem engineers likely had cascading effects on plant communities and landscapes throughout North America.

Ecological Impact and Legacy

Giant ground sloths were not merely passive components of ancient ecosystems but active shapers of their environments. As massive herbivores consuming hundreds of pounds of plant material daily, they would have influenced vegetation patterns through selective feeding and physical disturbance. Many North American plant species show characteristics suggesting adaptation to megafaunal dispersal—large fruits with tough seeds that pass intact through digestive systems, or defensive structures like spines on lower portions of trunks and branches. The iconic Joshua tree of the American Southwest may represent one such coevolved species, with some researchers proposing that its current limited reproduction results partly from the loss of ground sloths as seed dispersers. Ground sloths likely created and maintained woodland clearings through their feeding activities, contributing to habitat diversity that benefited smaller creatures. Their dung would have redistributed nutrients across landscapes, enhancing soil fertility in concentrated areas. The disappearance of these ecological engineers thus represented more than just the loss of charismatic megafauna—it fundamentally altered ecosystem processes that had evolved over millions of years. Understanding these relationships helps scientists better interpret modern ecological patterns and conservation challenges.

Scientific Discoveries and Famous Specimens

Several remarkable fossil discoveries have advanced our understanding of giant ground sloths over the past two centuries. Among the most significant was the recovery of a nearly complete Megalonyx skeleton from a fissure in West Virginia’s Organ Cave system in the 1990s, providing unprecedented insights into this species’ anatomy. The Rancho La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles have yielded thousands of Harlan’s ground sloth (Paramylodon harlani) specimens, allowing researchers to study population-level variations and pathologies. Perhaps most spectacular are the preserved remains from cave sites across the southwestern United States, including Rampart Cave in Arizona and Gypsum Cave in Nevada, where mummified tissue, hair, and dung have survived for millennia in the arid conditions. In 2010, an underwater cave exploration in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula revealed a nearly complete Eremotherium skeleton alongside human remains, adding evidence to the human-sloth interaction hypothesis. Each major discovery has refined our image of these creatures, transforming them from theoretical reconstructions to tangible beings with specific adaptations and life histories. Continued exploration of caves, sinkholes, and underwater sites promises to yield further insights into these fascinating mammals that once dominated North American landscapes.

Modern Descendants: Today’s Tree Sloths

The gentle tree sloths of Central and South America represent the last surviving branch of the once diverse sloth lineage. Modern sloths belong to two families—the three-fingered sloths (Bradypodidae) and the two-fingered sloths (Megalonychidae)—with six species recognized today. These arboreal specialists bear little superficial resemblance to their ground-dwelling ancestors, having evolved distinctive adaptations for life in the rainforest canopy. Modern sloths are much smaller, typically weighing between 8-17 pounds, and have developed extraordinarily slow metabolisms that allow them to subsist on nutritionally poor leaves. Their fur hosts specialized ecosystems of algae, moths, and beetles—symbiotic relationships that likely didn’t exist in their terrestrial ancestors. Despite these differences, modern sloths share fundamental skeletal characteristics with their extinct relatives, including similar skull shapes and dental patterns. They represent the end product of a once-diverse group that explored numerous ecological niches across the Americas. Conservation efforts to protect today’s sloths take on added significance when viewed through this evolutionary lens—they are the last representatives of an ancient lineage that once included some of the largest land mammals in North America.

Conclusion

The giant ground sloths of North America represent one of the continent’s most fascinating prehistoric chapters. For millions of years, these massive, deliberate creatures shaped ecosystems, influenced plant distributions, and successfully adapted to changing climates. Their coexistence with early humans—however brief—forms a poignant moment in North American natural history, representing one of the few instances when our species encountered such otherworldly megafauna. Though absent from modern landscapes, their legacy persists in the distribution patterns of plants, in the genetic makeup of their arboreal descendants, and in the scientific discoveries that continue to illuminate their remarkable lives. As we face modern biodiversity challenges, understanding the complex factors behind their disappearance provides valuable context for conservation efforts today. The story of giant ground sloths reminds us that North America’s wilderness once supported a far more diverse and spectacular assemblage of life than what we see in the present day.