The prehistoric world of dinosaurs was dramatically different from our modern landscape. When we imagine dinosaurs feeding, we often picture Tyrannosaurus rex tearing into prey or Brachiosaurus stretching its long neck to reach treetops. But what exactly were those plants they consumed? While modern favorites like potatoes, corn, and roses were nowhere to be found, the Mesozoic Era (252-66 million years ago) boasted a rich diversity of plant life that fueled dinosaur ecosystems. From towering conifers to primitive flowering plants, the vegetation of the dinosaur age tells a fascinating story of plant evolution and prehistoric dietary patterns that shaped the development of these magnificent creatures.

The Ancient Plant World: A Different Green Planet

The world of plants during the Mesozoic Era was almost unrecognizable compared to our modern landscape. Flowering plants (angiosperms) were just beginning to evolve in the late Cretaceous period, meaning that for much of dinosaur history, they were nonexistent or rare. Instead, the landscape was dominated by gymnosperms—plants that reproduce through exposed seeds rather than flowers and fruits. Giant conifers, cycads, ginkgoes, and ferns created vast forests and undergrowth that would appear alien yet familiar to modern eyes. The absence of grasses meant that open fields as we know them today simply didn’t exist, replaced instead by fern prairies and horsetail marshes. The color palette was also different, with fewer bright flowers and fruit colors, creating a world primarily painted in shades of green and brown.

Cycads: Palm-Like Plants with Prehistoric Appeal

Cycads were among the most important food sources for many herbivorous dinosaurs, particularly during the Jurassic period. These plants, which resemble palm trees but are not closely related to them, feature stiff, feather-like leaves radiating from a central trunk and produce large cones containing seeds. Some cycads grew to impressive heights of up to 30 feet, while others remained more shrubby in stature. Modern cycads are considered living fossils, looking remarkably similar to their Mesozoic ancestors, though today they’re much less abundant and diverse. Sauropods like Brachiosaurus likely fed heavily on cycad fronds, stripping them from the trunks with their peg-like teeth. The high fiber content and tough exterior of cycads suggest that dinosaurs had highly efficient digestive systems to extract nutrients from these plants.

Ginkgoes: The Resilient Survivors

Ginkgo trees represent one of the most remarkable success stories in plant evolution, with Ginkgo biloba being the only surviving species of a lineage that thrived during dinosaur times. During the Mesozoic, numerous ginkgo species created forests across the globe, their distinctive fan-shaped leaves carpeting the forest floor when shed. These trees were remarkably resilient, capable of surviving in various climates and conditions, which partly explains their evolutionary longevity. Herbivorous dinosaurs would have browsed their leaves and possibly consumed their fleshy, fruit-like seeds, though these contained compounds that might have been mildly toxic if eaten in large quantities. The high prevalence of ginkgo fossils alongside dinosaur remains suggests they were an important component of many dinosaur diets, particularly for medium-height browsers like Stegosaurus and younger sauropods.

Conifers: The Skyscrapers of the Mesozoic

Conifer trees were the true giants of the Mesozoic landscape, forming vast forests that resembled some modern woodland areas but with distinctive differences. Ancient relatives of today’s pines, redwoods, and araucarias grew to massive heights, creating multi-layered forest canopies that supported diverse ecosystems. The largest herbivorous dinosaurs, particularly the long-necked sauropods like Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus, evolved their spectacular heights partly in response to these tall food sources. The energy-rich seeds produced in conifer cones would have been valuable food sources for smaller dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Fossil evidence shows distinctive bite marks on ancient conifer wood, suggesting that some dinosaurs stripped bark or browsed young branches. The resinous nature of many conifers might have made them less palatable to some herbivores, potentially explaining why some dinosaurs developed specialized feeding strategies or digestive adaptations.

Ferns: Understory Staples for Dinosaur Diets

Ferns represented a critical food source for many herbivorous dinosaurs, particularly those that fed close to the ground. Unlike today, where ferns typically occupy niche environments, Mesozoic ferns were incredibly diverse and abundant, forming vast “fern prairies” in some regions. These plants reproduce via spores rather than seeds, creating dense undergrowth in forests and dominating disturbed areas after events like fires or floods. Smaller ornithischian dinosaurs like Hypsilophodon and Lesothosaurus likely specialized in feeding on ferns, as suggested by their dental adaptations for cropping these plants. The high silica content in many fern species would have made them quite abrasive, contributing to the distinctive tooth wear patterns observed in many herbivorous dinosaur fossils. Some larger “tree ferns” with trunks reaching 20 feet or more would have provided browsing opportunities for taller dinosaurs as well.

Horsetails: Ancient Relatives of Modern Equisetum

Horsetails, belonging to the genus Equisetum and their extinct relatives, were significantly more diverse and larger during the age of dinosaurs than their modern descendants. While today’s horsetails rarely exceed a few feet in height, Mesozoic species could reach sizes comparable to small trees, with some calamite relatives growing to heights of 30 feet or more. These plants typically grew in wet, marshy environments, creating dense thickets along waterways and swamps. Their jointed stems, containing silica that gives them their characteristic rough texture, would have posed a challenge for dinosaur digestive systems. Nevertheless, fossil evidence suggests that many dinosaurs, particularly hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), consumed large quantities of these plants. The high abundance of horsetails in certain fossil assemblages alongside dinosaur remains indicates they were an important dietary component, particularly in wetland environments.

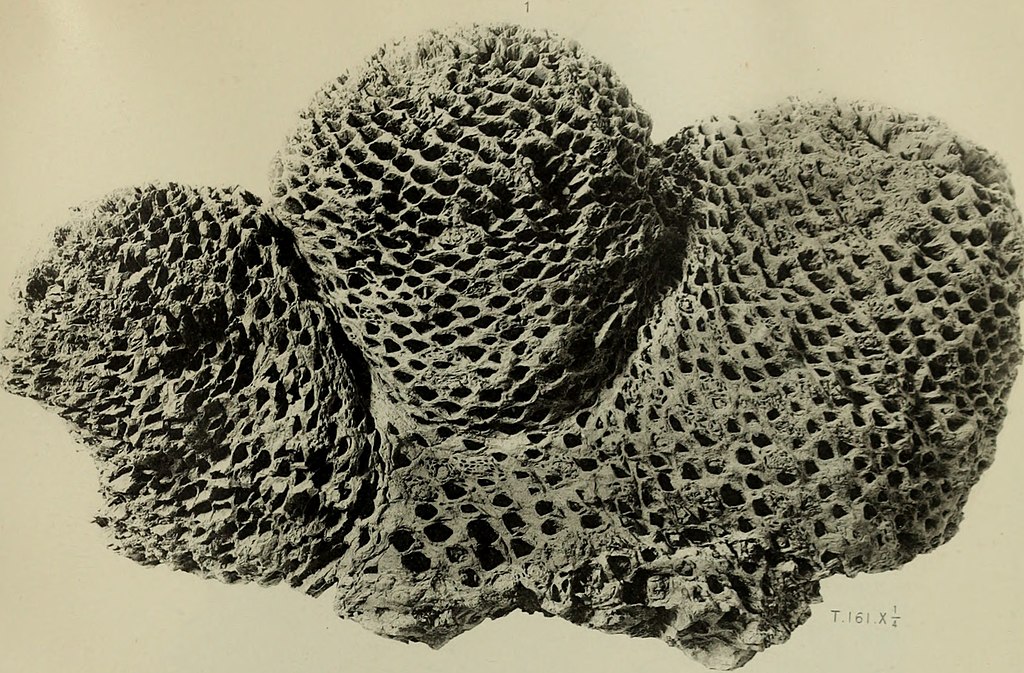

Bennettitales: The “Cycadeoids” That Vanished

Bennettitales, sometimes called cycadeoids due to their superficial resemblance to cycads, represented a now-extinct group of plants that were highly significant during dinosaur times. Unlike true cycads, bennettitaleans produced structures that resembled flowers, making them an evolutionary puzzle piece between non-flowering and flowering plants. Some species developed short, stocky trunks crowned with leaf clusters, while others displayed more branching growth habits. Their reproductive structures produced fleshy, nutritious tissues that would have attracted various dinosaur species as food sources. Notably, these plants completely disappeared by the end of the Cretaceous period, coinciding with the dinosaur extinction event. Paleobotanists have suggested that their relationship with dinosaur herbivores might have been so specialized that the disappearance of their main consumers contributed to their ultimate extinction.

The Dawn of Flowering Plants

The evolution of flowering plants (angiosperms) represents one of the most significant botanical developments during dinosaur times, occurring primarily during the Cretaceous period, roughly 125-100 million years ago. This plant revolution coincided with the diversification of certain dinosaur groups, particularly hadrosaurs and ceratopsians, whose specialized teeth and jaws may have evolved partly in response to these new food sources. Early angiosperms were likely small, shrubby plants bearing simple flowers and primitive fruits rather than the showy blooms we associate with flowering plants today. Magnolia relatives were among the earliest flowering plants, along with ancestors of water lilies and plants related to modern pepper plants. Some paleontologists propose that dinosaur consumption and dispersal of early angiosperm seeds may have contributed to the rapid spread and diversification of flowering plants, creating one of the most important plant-animal relationships in Earth’s history.

Specialized Diets: How Different Dinosaurs Adapted to Plant Options

Dinosaur herbivores developed remarkably specialized adaptations to exploit different plant food sources available during the Mesozoic. Sauropods, with their long necks and column-like legs, could reach high into conifer and ginkgo canopies that other dinosaurs couldn’t access, effectively dividing the vertical feeding space. Stegosaurs and ankylosaurs, with their relatively low-slung bodies, specialized in consuming ferns and low-growing vegetation, using their narrow beaks to selectively crop plants. Perhaps most specialized were the hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), which evolved complex dental batteries composed of hundreds of teeth that continuously replaced themselves, allowing these animals to process tough, fibrous plant materials through grinding motions. Ceratopsians like Triceratops used their sharp beaks to snip through resistant vegetation, while their powerful jaws and shearing dental arrangements processed even woody plant materials. These specializations created ecological niches that allowed multiple herbivore species to coexist in the same habitat while utilizing different plant resources.

Forests and Landscapes of the Dinosaur Era

The landscapes inhabited by dinosaurs varied dramatically by period and geography, creating diverse ecosystems across the Mesozoic world. During the early Triassic, when dinosaurs first appeared, the world was still recovering from the devastating Permian extinction, with relatively simple plant communities dominated by seed ferns and conifers. By the Jurassic period, when gigantic sauropods reached their apex, vast conifer forests with cycad understories prevailed in many regions, while fern prairies occupied open areas. The Cretaceous period saw increasingly complex plant communities, with the addition of flowering plants creating more diverse forest structures and the first primitive “meadows.” Unlike today, there were no grasslands, as grasses wouldn’t evolve until after the dinosaurs disappeared. Seasonal changes would have affected dinosaur feeding patterns significantly, with evidence suggesting some species migrated following food availability while others adapted to seasonal food scarcity through behavioral or physiological mechanisms.

Plant Defenses Against Dinosaur Diners

Just as plants today have evolved defenses against browsing mammals, Mesozoic plants developed various protective strategies against dinosaur consumption. Physical defenses were common, with many plants producing tough, fibrous tissues, silica-reinforced stems (as in horsetails), or spiny structures that would deter casual browsing. Chemical defenses likely played an even more important role, with toxic compounds serving as a deterrent against overconsumption. Some cycads, for instance, contain neurotoxic compounds in their tissues that can cause paralysis if consumed in large quantities, suggesting dinosaurs may have limited their intake of these plants. Growth strategies also served as defense mechanisms, with some conifers investing resources in rapid vertical growth to place their most nutritious foliage beyond the reach of all but the tallest browsers. The evolutionary arms race between plants and their dinosaur consumers likely drove adaptations on both sides, contributing to the diversity of both plants and dinosaur feeding strategies throughout the Mesozoic.

Fossil Evidence: How We Know What Dinosaurs Ate

Paleontologists employ several ingenious methods to determine the dietary preferences of extinct dinosaurs. Perhaps most directly, rare fossilized stomach contents provide a snapshot of an animal’s last meal, with preserved plant fragments identifying specific foods consumed. Coprolites (fossilized feces) offer additional evidence, containing partially digested plant remains that can be identified to genus level in well-preserved specimens. Dental morphology provides crucial indirect evidence, as teeth adapted for slicing, crushing, or grinding reflect specialized feeding strategies tailored to particular plant types. Microscopic wear patterns on fossil teeth can reveal whether a dinosaur was consuming soft leaves, woody materials, or abrasive plants like horsetails. Stable isotope analysis of fossilized bones and teeth can distinguish between animals consuming different plant types, as C3 plants (most Mesozoic species) and C4 plants (rare during dinosaur times) leave distinctive chemical signatures. Together, these lines of evidence allow researchers to reconstruct prehistoric food webs with increasing accuracy, painting a comprehensive picture of dinosaur-plant relationships.

How Plant Life Shaped Dinosaur Evolution

The coevolution between plants and dinosaurs represents one of the most significant and enduring evolutionary relationships in Earth’s history. As plants developed new growth forms, defensive compounds, and reproductive strategies, dinosaurs evolved corresponding adaptations to exploit these resources. The tremendous size of sauropods, for instance, likely evolved partly in response to the height of conifer forests, allowing these giants to access food sources unavailable to smaller competitors. The diversification of ornithischian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous period coincided with the radiation of flowering plants, suggesting these herbivores adapted to exploit these new food sources. Some researchers propose that certain dinosaur groups may have served as important seed dispersers for early flowering plants, potentially carrying seeds in their digestive tracts across large distances. This interdependence between dinosaurs and their plant food sources underscores how ecological relationships drive evolutionary trajectories, with changes in plant communities rippling through the entire ecosystem to shape animal evolution.

The Ancient Flora That Fed the Dinosaurs

The plant world of the Mesozoic era provided the foundation for dinosaur dominance across the planet. From towering conifers to primitive flowering plants, this green backdrop supported the evolutionary theater where dinosaurs played out their 165-million-year success story. Unlike our modern world with potatoes, grasses, and familiar fruits, dinosaurs browsed on cycads, ginkgoes, and ancient relatives of today’s plants. As paleobotanists and paleontologists continue unearthing new fossils and developing advanced analytical techniques, our understanding of this ancient plant-dinosaur relationship grows increasingly sophisticated. The story of what dinosaurs ate isn’t just about prehistoric diets—it reveals the intricate ecological dance between plant evolution and animal adaptation that has shaped life’s journey on Earth across hundreds of millions of years.