Deep in the rivers and wetlands of ancient Earth, a remarkable predator once prowled that challenged our understanding of mustelid evolution. Siamogale melilutra, a giant prehistoric otter that lived approximately 6 million years ago, combined the stealth of an otter with the hunting prowess of a big cat. This extraordinary creature, significantly larger than any modern otter species, dominated its ecosystem through a unique combination of anatomical adaptations and predatory behaviors. Recent paleontological discoveries have revealed fascinating insights into this ancient hunter’s lifestyle, bringing to light a creature that represents one of the most remarkable examples of convergent evolution in mammalian history.

The Discovery of Siamogale melilutra

The first fossils of Siamogale melilutra were uncovered in Yunnan Province, southwestern China, during extensive paleontological excavations in the early 2010s. Scientists were initially puzzled by these remains, which exhibited characteristics of both otters and badgers—hence the species name “melilutra,” combining the Latin terms for badger (meles) and otter (lutra). The discovery site, situated in what was once a lush wetland ecosystem, yielded remarkably complete skeletal specimens including a well-preserved skull and jawbone. Further expeditions unearthed additional specimens in neighboring regions, allowing researchers to piece together a comprehensive understanding of this ancient predator’s appearance and lifestyle. The exceptional preservation quality of these fossils enabled scientists to conduct detailed anatomical analyses using cutting-edge technologies like CT scanning and computer modeling.

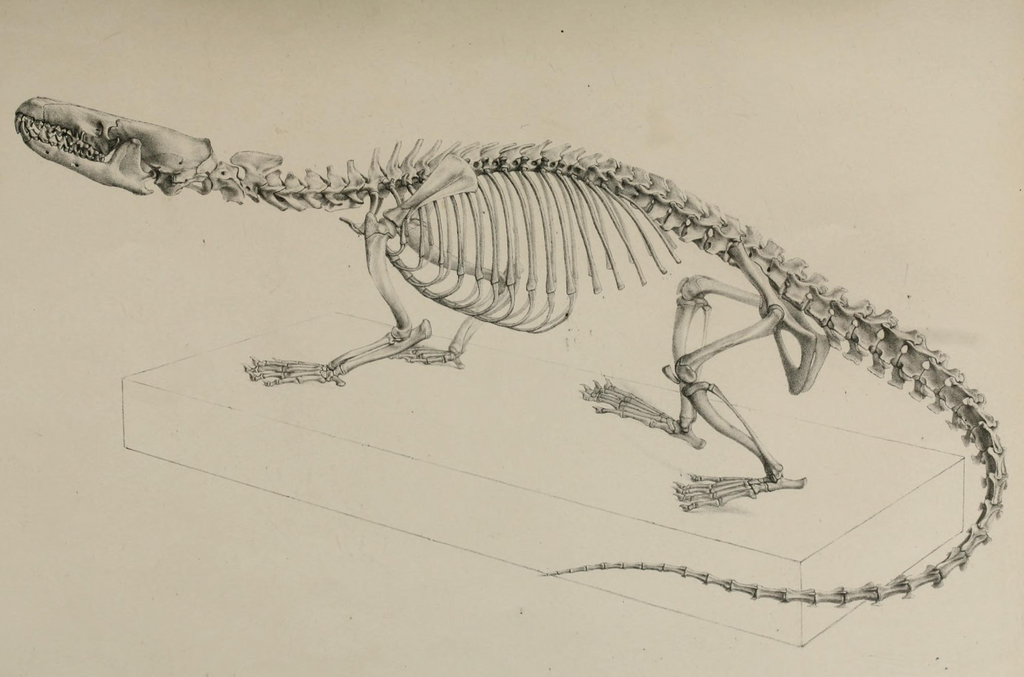

Size and Physical Characteristics

Siamogale melilutra was a true giant among otters, weighing approximately 110 pounds (50 kilograms)—roughly twice the size of the modern sea otter and six times larger than the average river otter. Its robust skull measured nearly 8 inches (20 centimeters) in length, equipped with powerful jaws and sharp teeth adapted for crushing hard-shelled prey. Unlike modern otters with their sleek, elongated bodies, Siamogale possessed a stockier, more muscular build reminiscent of wolverines or small bears. Its limbs were shorter and more powerful than those of contemporary otters, suggesting a different locomotion style that combined swimming proficiency with significant land mobility. Perhaps most striking was its unusually strong jaw structure, which paleontologists have described as capable of delivering devastating crushing force disproportionate even to its considerable size.

Jaw Structure and Crushing Power

The most remarkable feature of Siamogale melilutra was its extraordinarily powerful jaws, which researchers have determined possessed bone-crushing capabilities far exceeding those of modern otters. Using sophisticated biomechanical modeling techniques, scientists determined that this prehistoric otter had evolved specialized jaw muscles and reinforced bone structures that could generate tremendous bite forces. These adaptations allowed Siamogale to access food sources unavailable to many other predators, such as hard-shelled mollusks, turtles, and heavily armored crustaceans. CT scans revealed that the cranial architecture distributed bite forces efficiently across the skull, preventing structural damage during powerful crushing actions. This exceptional jaw strength represents a remarkable case of evolutionary specialization, allowing Siamogale to occupy a unique ecological niche between aquatic and terrestrial hunting domains.

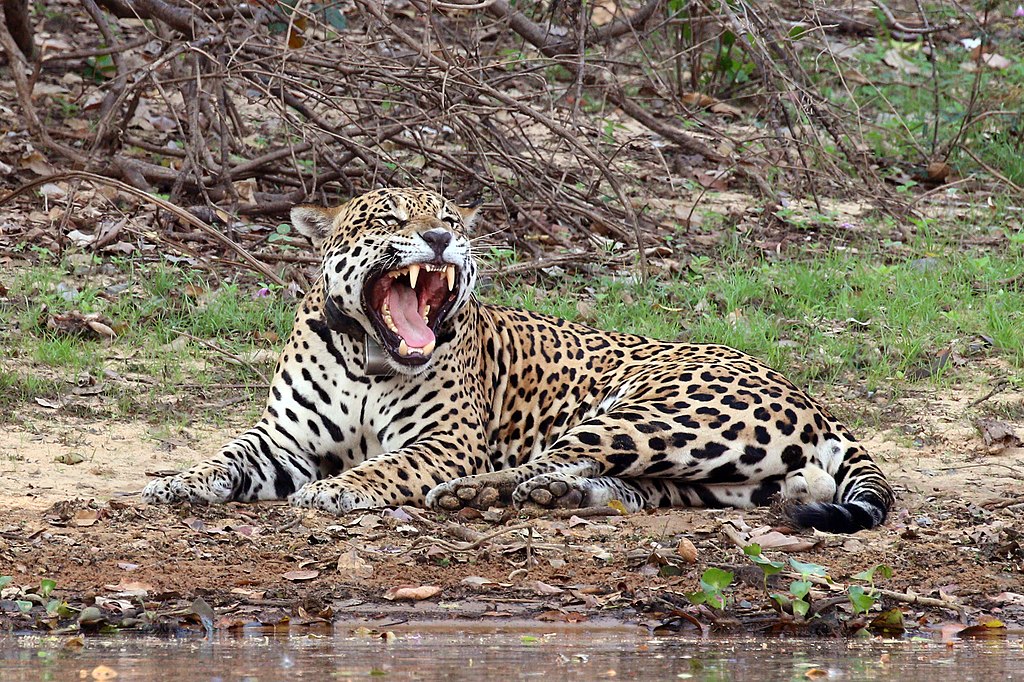

Hunting Strategies: The Jaguar Connection

The comparison between Siamogale and jaguars stems from fascinating parallels in their hunting specializations despite evolving in completely different lineages and environments. Like modern jaguars, which are renowned for their ability to crack turtle shells and pierce the armored plates of caimans, Siamogale evolved specialized crushing abilities that allowed it to access prey with hard protective coverings. Paleobiologists theorize that Siamogale employed ambush hunting techniques similar to those used by big cats, potentially stalking prey both in water and on shorelines. The otter’s powerful build would have enabled short bursts of speed, while its crushing jaws delivered lethal attacks to vital areas of prey animals. This convergent evolution with felids represents a remarkable case of different mammalian groups independently developing similar predatory adaptations in response to comparable ecological pressures.

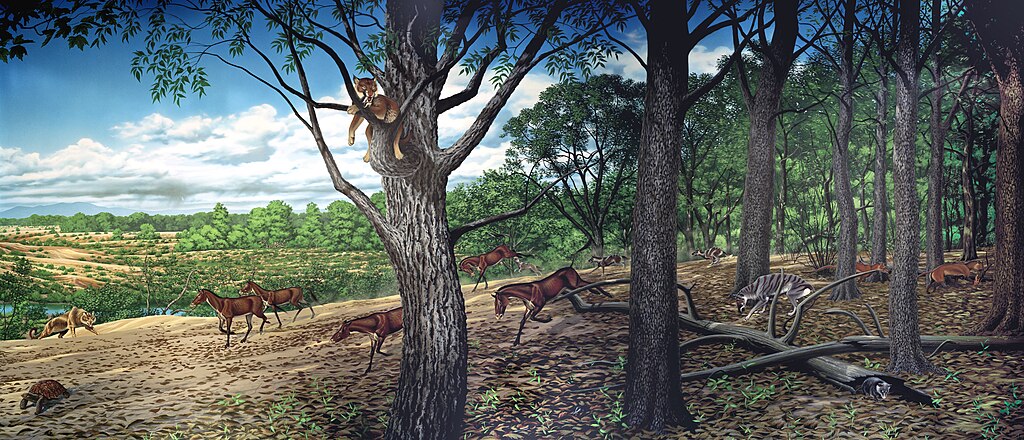

Habitat and Ancient Ecosystems

During the late Miocene period when Siamogale melilutra thrived, its habitat in what is now southwestern China consisted of expansive wetland systems interspersed with lush forests and grasslands. Paleoenvironmental reconstructions indicate a subtropical climate supporting diverse aquatic ecosystems teeming with fish, mollusks, and crustaceans—all potential prey for the giant otter. The region featured extensive river networks and seasonal floodplains where Siamogale likely established territorial ranges spanning both aquatic and terrestrial environments. Fossil evidence suggests these otters frequented shallow lake margins and slow-moving watercourses where hunting would have been most productive. The rich biodiversity of this ancient wetland ecosystem provided abundant resources that could support such large-bodied predators, allowing Siamogale to evolve its specialized hunting adaptations in response to this environment’s particular challenges and opportunities.

Dietary Preferences and Feeding Ecology

Analysis of Siamogale’s dentition and jaw structure provides compelling evidence about its dietary habits, revealing a predator with remarkably diverse feeding capabilities. While modern otters typically specialize in fish consumption, Siamogale appears to have maintained a much broader diet including freshwater mollusks, turtles, crustaceans, and various vertebrates. Microwear patterns on preserved teeth suggest regular interaction with hard-shelled prey, confirming the hypothesis that its crushing abilities were actively employed in feeding. Isotopic analyses of fossil remains have indicated that Siamogale occupied an apex predator position in its food web, consuming prey from multiple trophic levels. The ability to process such a wide variety of food resources, including items inaccessible to other predators, likely contributed significantly to Siamogale’s evolutionary success and allowed it to weather seasonal changes in prey availability while maintaining its impressive body size.

Evolutionary History and Mustelid Relationships

Siamogale melilutra belongs to the family Mustelidae, which includes modern otters, badgers, weasels, and wolverines, but represents a distinct branch that has no direct descendants among living species. Phylogenetic analyses place it within a now-extinct subfamily of otters that diverged from the lineage leading to modern otter species approximately 18 million years ago. This evolutionary positioning challenges previous assumptions about mustelid evolution, suggesting that giant size and specialized crushing abilities evolved independently multiple times within otter lineages. Genetic comparisons with other fossil mustelids indicate that Siamogale likely shared a common ancestor with both modern otters and badgers, explaining its curious combination of characteristics from both groups. The extinction of Siamogale and related species created an evolutionary gap in the mustelid family tree, representing a fascinating “road not taken” in the subsequent diversification of otter species.

Social Structure and Behavior

While behavioral characteristics are difficult to determine from fossil evidence alone, paleobiologists have developed compelling hypotheses about Siamogale’s social structure based on comparisons with modern mustelids and the ecological pressures it faced. The concentration of multiple individuals in certain fossil deposits suggests that Siamogale may have maintained some degree of social organization, potentially living in family groups similar to some modern otter species. Its large size and predatory capabilities would have reduced pressure from predation, potentially allowing for more complex social interactions than typically seen in smaller mustelids. Environmental factors, including seasonal resource availability in its wetland habitat, likely influenced group dynamics and territorial behaviors. Some researchers have proposed that Siamogale might have engaged in cooperative hunting strategies to tackle larger prey, though this remains speculative without direct behavioral evidence from the fossil record.

Adaptations for Amphibious Living

Despite its jaguar-like hunting specializations, Siamogale retained crucial adaptations for life in aquatic environments, demonstrating its evolutionary position as a true semi-aquatic mammal. Skeletal evidence indicates that while more robustly built than modern otters, Siamogale possessed adaptations for efficient swimming, including a strong, flexible spine and powerful limbs that could provide propulsion in water. Analysis of the nasal structure suggests specialized adaptations for closing the nostrils while submerged, a feature common in aquatic mammals. The creature’s body proportions struck a balance between aquatic streamlining and terrestrial mobility, allowing it to move effectively between environments. Researchers have identified specialized bone density patterns similar to those seen in diving mammals, suggesting Siamogale could pursue prey underwater for extended periods, though likely not as proficiently as fully aquatic species.

Comparison with Modern Otters

The contrast between Siamogale and contemporary otter species highlights the remarkable diversity within the mustelid family across evolutionary time. While the largest modern otter, the sea otter (Enhydra lutris), can reach up to 100 pounds, it employs fundamentally different hunting strategies than Siamogale, using tools rather than jaw strength to access hard-shelled prey. Modern river otters are significantly smaller and more specialized for piscivorous diets, lacking the crushing capabilities that defined Siamogale’s ecological niche. The giant prehistoric otter’s skull morphology shows greater similarities to modern badgers and wolverines than to living otter species, suggesting independent evolution of adaptations for hard-object feeding. Modern otters have evolved more streamlined body shapes optimized for aquatic agility, while Siamogale maintained a compromise build that sacrificed some swimming efficiency for greater power and terrestrial capability.

Extinction and Environmental Change

The fossil record indicates that Siamogale melilutra disappeared approximately 5.3 million years ago, coinciding with significant environmental changes at the Miocene-Pliocene boundary. Climate shifts during this period led to cooling and drying trends across much of Asia, transforming many of the lush wetlands that had supported Siamogale’s specialized lifestyle. Paleoclimatic evidence suggests that the extensive shallow water ecosystems where these predators thrived underwent fragmentation and reduction, limiting available habitat and prey resources. Competition from emerging carnivore groups, including early canids and felids with different hunting specializations, may have further pressured Siamogale populations as environmental conditions changed. The extinction of this remarkable predator illustrates how even highly specialized and successful species can become vulnerable when faced with relatively rapid environmental transformations that affect their ecological niche.

Significance in Paleontological Research

The discovery and ongoing study of Siamogale melilutra has profound implications for our understanding of mammalian evolution and predator ecology in ancient ecosystems. This remarkable creature provides a compelling case study in convergent evolution, demonstrating how similar ecological pressures can produce comparable adaptations in distantly related animal groups—in this case, between mustelids and felids. The exceptional preservation of Siamogale fossils has enabled researchers to apply cutting-edge analytical techniques including 3D morphometrics, finite element analysis, and molecular paleontology to reconstruct its biology in unprecedented detail. Ongoing research into this species continues to challenge conventional understanding of carnivore evolution and provides valuable insights into how complex feeding adaptations develop in response to environmental opportunities. Siamogale represents a crucial reference point for understanding the diversity of extinct predators and interpreting the evolutionary history of mustelids as a family.

Contemporary Scientific Discoveries

Recent technological advances have revolutionized our understanding of Siamogale melilutra, with new findings emerging regularly as research techniques improve. In 2017, scientists at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History utilized advanced CT scanning and digital reconstruction to model the biomechanics of Siamogale’s jaw, confirming its exceptional crushing capabilities through computer simulations. Ancient DNA extraction attempts, while challenging with specimens of this age, have yielded fragmentary genetic information that helps position Siamogale more precisely within the mustelid family tree. Ongoing excavations in Asia continue to uncover additional specimens, gradually expanding our sample size and geographical understanding of this species’ distribution. Most recently, microscopic analysis of preserved tooth surfaces has provided direct evidence of diet through identification of wear patterns consistent with crushing shellfish and other hard-bodied prey, validating theoretical models of this animal’s feeding ecology with physical evidence.

The prehistoric giant otter Siamogale melilutra represents one of nature’s most fascinating evolutionary experiments—a mustelid that evolved to fill a niche similar to that of big cats in modern ecosystems. With its jaguar-like hunting capabilities combined with semi-aquatic adaptations, this remarkable predator dominated the wetlands of ancient Asia for millions of years before environmental changes led to its extinction. Through continued paleontological research, Siamogale provides valuable insights into convergent evolution, predator-prey relationships, and the remarkable adaptability of mammalian carnivores throughout Earth’s history. As new specimens and analytical techniques emerge, our understanding of this extraordinary creature continues to evolve, offering a window into a lost world where otters grew to the size of wolves and hunted with the power of big cats.