In the fascinating world of prehistoric creatures, dinosaurs continue to surprise paleontologists with their unique adaptations and behaviors. Among the most intriguing recent discoveries is evidence suggesting certain dinosaur species may have used their heads as battering tools—essentially living hammers. Pachycephalosaurs, a group of dome-headed dinosaurs, have long puzzled scientists with their unusual cranial structures. New research provides compelling evidence that these thick-skulled dinosaurs engaged in head-butting behaviors similar to modern rams or musk oxen, but potentially even more dramatic. This remarkable adaptation offers a window into the complex social and competitive behaviors that shaped dinosaur evolution and survival strategies in the Cretaceous period.

Meet the Pachycephalosaurs: The Thick-Skulled Dinosaurs

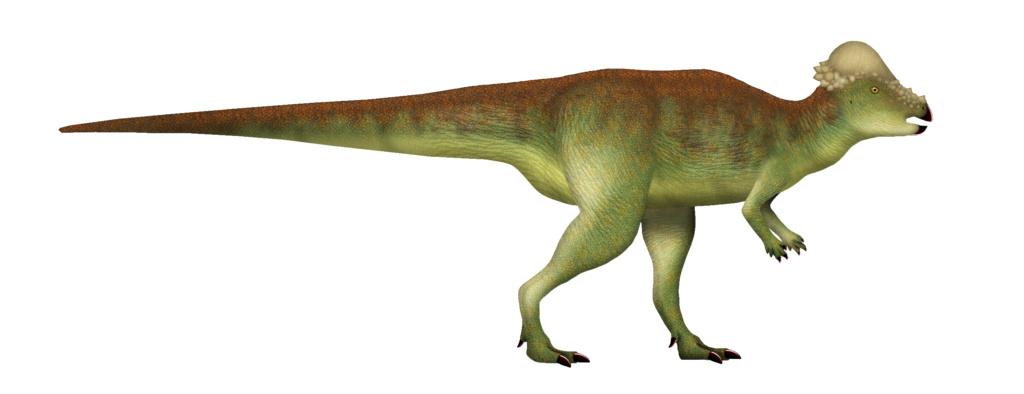

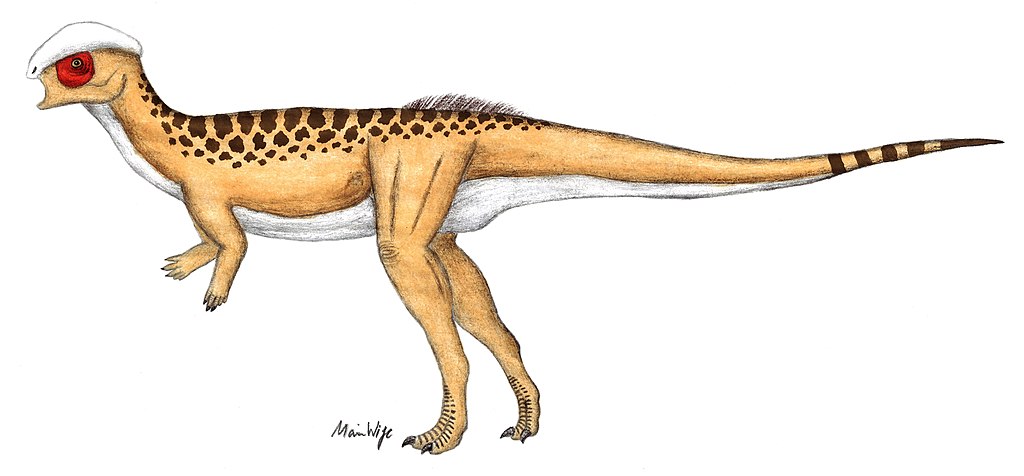

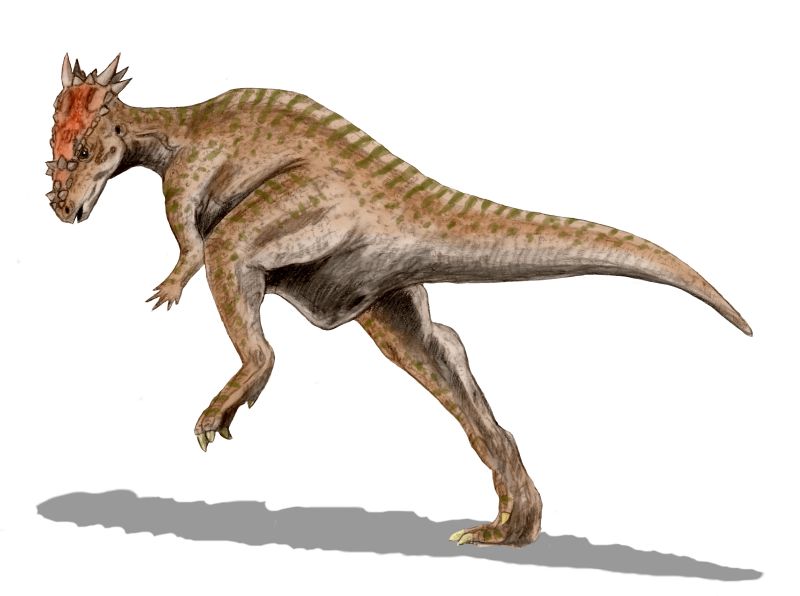

Pachycephalosaurs were bipedal, herbivorous dinosaurs that lived during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 85-65 million years ago. Their most distinctive feature was their incredibly thick skull dome, which in some species could reach up to 10 inches in thickness. This group includes well-known species like Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis, Stegoceras, and Dracorex hogwartsia. The name “pachycephalosaur” literally translates to “thick-headed lizard,” aptly describing their most notable characteristic. These medium-sized dinosaurs typically measured between 4.5 to 15 feet in length and weighed between 300 to 990 pounds, making them relatively small compared to giants like Tyrannosaurus rex but still formidable in their own right. Their remains have been found primarily in North America and Asia, suggesting they were widespread across the Northern Hemisphere during their existence.

The Extraordinary Dome: A Biological Helmet

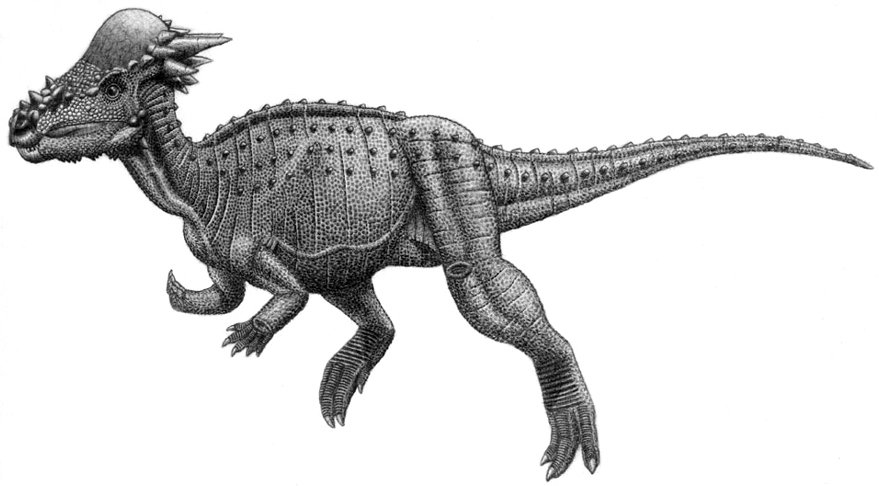

The pachycephalosaur’s dome is one of the most specialized structures known in dinosaur anatomy. This remarkable feature consisted of a solid bone mass up to 10 inches thick in some species, formed from the fusion and thickening of the frontal and parietal bones of the skull. Unlike hollow or pneumatic bones found in many dinosaurs, these domes were composed of dense, solid bone surrounded by a network of blood vessels. The bone itself had a unique internal structure with three distinct layers: a dense outer layer, a middle layer of spongy bone for absorbing impact, and a more compact inner layer protecting the brain. This specialized construction created a natural helmet-like structure that could withstand tremendous force. Surrounding the dome in many species were decorative spikes and nodes that protruded from the back and sides of the skull, creating an even more impressive cranial display that likely served both defensive and display purposes.

Evidence of Head-Butting Behavior

The hypothesis that pachycephalosaurs used their heads as biological hammers is supported by multiple lines of evidence. Microscopic studies of pachycephalosaur skull domes have revealed healing fractures and stress marks consistent with repeated high-impact collisions. Computer modeling and biomechanical analysis demonstrate that their unique skull structure was capable of absorbing significant impact forces without causing fatal damage to the brain. Comparative studies with modern head-butting animals like bighorn sheep and musk oxen show remarkable convergent evolution in skull structure, despite being separated by millions of years of evolution. Additionally, the neck vertebrae of pachycephalosaurs show adaptations consistent with absorbing and distributing impact forces, including reinforced articulation points and enlarged attachment sites for powerful neck muscles. The distribution of these stress markers across multiple specimens suggests this behavior was common rather than isolated incidents of trauma, further supporting the head-butting hypothesis.

The Mechanics of Dinosaur Head-Butting

Recent biomechanical studies have illuminated how pachycephalosaurs might have executed their head-butting behaviors. Computer simulations suggest these dinosaurs likely charged at each other at speeds of approximately 10-15 miles per hour, generating tremendous force upon impact. The unique dome shape served to distribute impact forces across the skull rather than concentrating them at a single point, reducing the risk of fatal injury. Their strengthened neck muscles, evidenced by enlarged vertebral attachment points, would have stabilized the head during impact and helped absorb the shock. Unlike modern rams that primarily target each other’s horns, pachycephalosaurs likely engaged in direct dome-to-dome contact, with their thickened skulls perfectly evolved for this purpose. Some researchers propose they may have also engaged in flank-butting, where they targeted the sides of rivals rather than meeting head-on, which would have been potentially less dangerous while still demonstrating dominance. The slightly varied dome shapes among different pachycephalosaur species suggest they may have employed slightly different butting techniques specialized to their particular cranial morphology.

Competing Theories: Were They Really Head-Butters?

Despite compelling evidence for head-butting behavior, some paleontologists remain skeptical about this interpretation of pachycephalosaur anatomy. One alternative hypothesis suggests the dome may have primarily served as a visual display structure for mate attraction or species recognition rather than a battering tool. Others propose the thick skulls might have been used for flank-butting against predators as a defensive mechanism, rather than for competition within their own species. Some researchers point to the potential brain trauma that would result from high-velocity impacts as evidence against routine head-butting, arguing the behavior would have been unsustainable. Another competing theory suggests the domes might have been used for pushing contests similar to those seen in modern giraffes, involving more shoving than direct high-impact collisions. Histological studies of the bone microstructure have produced mixed results, with some samples showing stress patterns consistent with impact and others lacking such evidence, fueling continued debate in the scientific community about the primary function of these remarkable structures.

Social Implications: Why Butt Heads?

If pachycephalosaurs did indeed use their heads as natural hammers, this behavior likely served important social functions within their populations. The most widely accepted theory suggests head-butting was a form of male-to-male combat for establishing dominance hierarchies and earning mating privileges, similar to behaviors observed in modern bighorn sheep and musk oxen. This competition would have allowed females to select mates with the strongest genes, as evidenced by their ability to withstand powerful impacts. The spectacular domes may have also served as visual signals of health, maturity, and genetic quality even when not being used in active combat. Some paleontologists propose that head-butting behaviors might have played a role in territorial defense, with dominant individuals controlling access to prime feeding grounds. Juvenile pachycephalosaurs had significantly less developed domes, suggesting the behavior and its social implications likely increased in importance as individuals reached sexual maturity, further supporting its connection to reproductive success and social status within the herd.

Growth and Development of the Dome

The remarkable head dome of pachycephalosaurs wasn’t present from hatching but developed gradually throughout the dinosaur’s life. Fossil evidence from juvenile specimens shows that young pachycephalosaurs had relatively flat heads with only slight thickening of the skull roof. As individuals matured, their domes became progressively thicker and more prominent, reaching full development only in adult specimens. This ontogenetic (growth-related) change was so dramatic that juvenile and adult forms of the same species were initially classified as different genera until growth series were discovered. The blood vessel channels within the dome structure suggest it was a metabolically active region that required significant resources to develop and maintain. The energetic investment in creating such massive skull structures underscores their biological importance to these dinosaurs. Some species also showed sexual dimorphism in dome development, with presumed males developing larger, more elaborate domes than females, further supporting the theory that these structures played a role in competition for mates.

Different Dome Designs Among Species

The pachycephalosaur family displayed remarkable variation in dome architecture across different species, suggesting possible specialization for different types of head-butting behaviors or social displays. Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis possessed the most extreme dome development, with a massive, rounded skull cap that could reach 10 inches in thickness. Stegoceras had a more modestly developed dome with a distinctive ridge running along the midline, potentially allowing for more precise targeting during confrontations. Homalocephale, contrary to its relatives, maintained a relatively flat head throughout life, suggesting it may have utilized different social behaviors altogether. Dracorex and Stygimoloch, once thought to be distinct species, are now believed to represent different growth stages of Pachycephalosaurus, demonstrating how dramatically the dome structure changed throughout an individual’s lifetime. The varied ornamentation surrounding the domes, including spikes, nodes, and ridges, also differed significantly between species, potentially serving as species-recognition features that prevented wasteful combat between different kinds of pachycephalosaurs.

Head-Butting in the Modern World

The proposed head-butting behavior of pachycephalosaurs finds numerous parallels in modern animals, offering insights through comparative biology. Bighorn sheep are perhaps the most famous head-butters, with males charging each other at speeds up to 20 mph, their collisions audible from a mile away. Musk oxen engage in similar behaviors, using their reinforced skulls and specialized neck muscles to absorb tremendous impacts during dominance contests. Giraffes practice a less dramatic form of head combat called “necking,” where they swing their heads to strike opponents’ flanks. Pachycephalosaurs appear to have taken head-butting to extremes beyond what’s seen in modern animals, with skull adaptations proportionally more specialized than any living creature. Even modern birds, the direct descendants of dinosaurs, include species like the helmeted hornbill with reinforced head structures used in aerial jousting contests. These modern analogs help paleontologists reconstruct the behaviors of extinct animals through the principle of convergent evolution, where similar environmental pressures produce similar adaptations in unrelated species.

Technological Insights: How Science Confirmed the Hammer Theory

Modern scientific techniques have been crucial in evaluating the head-butting hypothesis for pachycephalosaurs. High-resolution CT scanning has allowed researchers to examine the internal structure of fossil skulls without damaging precious specimens, revealing the three-layered construction ideal for absorbing impacts. Finite element analysis, a computer modeling technique originally developed for engineering, has been applied to simulate stress distribution across pachycephalosaur skulls during hypothetical collisions. These simulations confirm the dome shape effectively dissipated impact forces while protecting the brain. Comparative histology of bone microstructure between pachycephalosaurs and modern head-butting animals has revealed similar patterns of remodeling associated with repeated stress. Biomechanical modeling incorporating factors like estimated body mass, neck muscle strength, and running speed has demonstrated that these dinosaurs could have physically executed head-butting behaviors without catastrophic injury. The convergence of evidence from these various independent analytical techniques has greatly strengthened the case for pachycephalosaurs as the hammer-headed dinosaurs, demonstrating how multidisciplinary approaches can provide insights into behaviors that occurred millions of years in the past.

Discoveries That Changed Our Understanding

Several key fossil discoveries have dramatically shaped our understanding of pachycephalosaur head-butting behavior over the years. The 2013 discovery of healing fractures and lesions on multiple pachycephalosaur domes provided the first direct evidence of traumatic injuries consistent with head-butting activities. A remarkably complete Pachycephalosaurus skeleton unearthed in Montana in 2006 revealed specialized neck vertebrae with adaptations for absorbing impact, supporting the biomechanical feasibility of head-butting behavior. The identification of growth series showing how dome development changed throughout life, particularly the recognition that Dracorex, Stygimoloch, and Pachycephalosaurus represent different growth stages of the same species, revolutionized our understanding of how these structures developed. Microscopic analysis of dome tissue published in 2018 revealed Sharpey’s fibers—attachment points for soft tissues—indicating substantial muscle attachment around the dome, necessary for withstanding high-impact forces. The discovery of multiple pachycephalosaur species with varied dome morphologies in close geographic proximity suggested these differences served as species recognition features, similar to how modern animals use distinctive horns or antlers to identify potential mates from the same species.

Beyond the Dome: Other Pachycephalosaur Adaptations

While the dome skull receives most attention, pachycephalosaurs possessed numerous other fascinating adaptations that contributed to their evolutionary success. Their dentition consisted of small, leaf-shaped teeth perfect for processing fibrous plant material, indicating a herbivorous diet despite their formidable appearance. Powerful hind limbs allowed pachycephalosaurs to run at considerable speeds, both for escape from predators and potentially for gaining momentum before head-butting contests. Their distinctive tall, narrow body profile with a stiffened tail may have provided the balance and stability needed to withstand the forces generated during high-impact collisions. Some species possessed bony scutes embedded in their skin, providing additional protection against predators in areas not covered by the reinforced skull. Pachycephalosaurs had relatively large eye sockets situated on the sides of their heads, providing excellent peripheral vision that would have been advantageous both for spotting predators and for targeting opponents during head-butting confrontations. These complementary adaptations demonstrate that pachycephalosaurs were highly specialized dinosaurs whose entire biology—not just their distinctive heads—was shaped by their unique ecological niche and behavioral strategies.

The Evolutionary Puzzle: How and Why Did This Trait Develop?

The evolution of the pachycephalosaur’s remarkable dome skull represents one of the most extreme cases of specialized morphology in dinosaur history. Paleontologists believe this feature evolved gradually, with early members of the lineage showing only modest thickening of the skull roof that became progressively more pronounced through natural selection. The primary evolutionary driver was likely sexual selection, where individuals with more impressive domes gained reproductive advantages through winning combat contests or attracting mates directly through visual display. The absence of comparable structures in most other dinosaur lineages suggests this represented a unique evolutionary experiment, possibly filling a specialized ecological and behavioral niche not exploited by other dinosaur groups. Fossil evidence indicates dome thickness increased over evolutionary time, suggesting continued selection pressure favoring more robust head structures. The pachycephalosaur lineage demonstrates how sexual selection can drive the evolution of extreme physical traits that might appear disadvantageous for survival but provide significant reproductive benefits. This evolutionary pattern parallels similar examples in modern animals, such as the massive antlers of Irish elk or the elaborate tail feathers of peacocks, where sexual selection drives the development of exaggerated features beyond what would be optimal for simple survival.

Conclusion: Hammerheads of the Prehistoric World

The compelling evidence that pachycephalosaurs used their distinctive dome-shaped skulls as biological hammers offers a fascinating glimpse into the complex behaviors of dinosaurs. These remarkable creatures, with their specialized skull architecture, reinforced neck vertebrae, and biomechanical adaptations, represent one of nature’s most extraordinary examples of morphological specialization. The head-butting hypothesis illuminates how social behaviors and competition for mates can drive the evolution of extreme physical traits, just as they do in many animals today. Though debate continues regarding the specific mechanics and purposes of these behaviors, the consensus increasingly supports the idea that pachycephalosaurs engaged in some form of head-centered combat or display. As paleontological techniques continue to advance, we may gain even more detailed insights into how these dinosaurs lived and interacted. For now, pachycephalosaurs stand as a testament to the remarkable diversity of dinosaur adaptations and a reminder that even creatures that lived 65 million years ago engaged in complex social behaviors that shaped their evolution in profound ways.