The evolutionary connection between birds and dinosaurs has fascinated scientists and the public alike for decades. At the heart of this relationship is one of nature’s most remarkable innovations: feathers. While many consider feathers the definitive evidence linking birds to their dinosaur ancestors, the complete picture is far more complex and fascinating. This evolutionary story involves not just feathers, but also bone structure, behavior, growth patterns, and an increasingly detailed fossil record that continues to yield discoveries. By examining multiple lines of evidence, we can better understand whether feathers truly represent the final proof in establishing birds as living dinosaurs, or if they’re just one piece of a more intricate evolutionary puzzle.

The Evolutionary Significance of Feathers

Feathers stand among nature’s most complex and specialized structures, having evolved from simple filaments to the intricate flight apparatus we see in modern birds. Initially, these structures likely served functions unrelated to flight—perhaps for insulation, display, or even waterproofing. The discovery of feathered non-avian dinosaurs in fossil beds, particularly in China’s Liaoning Province, revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur appearance and biology. These findings demonstrated that feathers weren’t exclusive to birds but appeared millions of years earlier in the evolutionary timeline. Specimens like Sinosauropteryx and Yutyrannus show that even some tyrannosaurs sported primitive feather-like structures, challenging our traditional scaly image of dinosaurs and supporting the evolutionary continuum between dinosaurs and birds.

Beyond Feathers: Skeletal Similarities

While feathers capture the imagination, the skeletal connections between birds and dinosaurs provide equally compelling evidence of their evolutionary relationship. Modern birds share numerous skeletal features with theropod dinosaurs—the group that includes Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus. Features such as hollow bones, fused clavicles forming a wishbone, and three-toed feet with a distinctive ankle structure appear in both groups. The wrist bones of many maniraptoran dinosaurs could fold against the body like modern birds, an adaptation crucial for wing-folding in flying species. Perhaps most telling is the presence of uncinate processes—small projections on the ribs that help with breathing—found in both birds and their dinosaur relatives but absent in other reptiles.

The Chinese Fossil Revolution

The fossil beds of northeastern China, particularly in Liaoning Province, have yielded what many consider the smoking gun in the birds-as-dinosaurs debate. Since the 1990s, these exceptionally preserved fossils have revealed dozens of feathered dinosaur species, many with preservation so fine that individual feather structures remain visible. Specimens like Microraptor, with its four wings and iridescent plumage, and Anchiornis, whose feather colors could be determined from fossilized melanosomes, provide unprecedented insights into dinosaur appearance. The temporal sequence of these fossils shows a clear progression from simple filamentous structures in earlier dinosaurs to the complex flight feathers of later species. This rich fossil record from China effectively closed many of the morphological gaps that once existed between dinosaurs and birds.

Feathers Before Flight: Their Original Purpose

Contrary to popular assumption, feathers didn’t evolve primarily for flight—their original functions were likely much different. The earliest feather-like structures probably served as insulation, helping dinosaurs regulate their body temperature in a manner similar to mammalian fur. This supports theories about dinosaur metabolism that suggest many species maintained elevated body temperatures, requiring insulation. Other early functions might have included display for mate attraction or species recognition, as seen in the elaborate feather crests of oviraptorosaurs. Some dinosaurs may have used feathers for camouflage or even parental care, creating nests where feathers helped incubate eggs. The diversity of feather types and distributions in non-flying dinosaurs indicates that these structures were evolving and adapting long before they enabled aerial locomotion.

The Transition to Flight-Capable Feathers

The evolution of pennaceous feathers—those with a central shaft and barbs forming a flat surface—represents a critical development in the dinosaur-bird transition. These structures, first appearing in non-flying dinosaurs, created the aerodynamic surfaces eventually necessary for flight. Fossils like Microraptor and Archaeopteryx show intermediate stages in this development, with asymmetrical flight feathers that weren’t yet as specialized as those in modern birds. The transition to flight-capable feathers involved multiple refinements, including the development of interlocking barbules that create a smooth, air-resistant surface. Modern bird feathers represent the culmination of this evolutionary process, with specialized structures for different functions: contour feathers for aerodynamics, down feathers for insulation, and modified feathers for display. This gradual refinement of feather structure across multiple dinosaur lineages provides compelling evidence for their evolutionary relationship with birds.

Molecular Evidence: Proteins and DNA

Beyond physical structures, molecular evidence has contributed significantly to our understanding of the dinosaur-bird connection. In a groundbreaking 2007 study, scientists extracted and sequenced proteins from a Tyrannosaurus rex specimen, finding that these molecules showed greater similarity to bird proteins than to those of other living reptiles. Similarly, analyses of collagen proteins from other dinosaur fossils reveal patterns consistent with birds being their closest living relatives. While ancient DNA rarely survives in fossils older than a million years, preventing direct genetic comparison with dinosaurs, the protein evidence serves as a molecular complement to the physical similarities observed in fossils. These biochemical findings support the morphological evidence that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs and retain molecular signatures of this ancestry.

Behavioral Connections: Nesting and Parental Care

The behavioral parallels between birds and their dinosaur ancestors extend beyond physical characteristics to complex behaviors like nesting and parental care. Numerous fossil discoveries show non-avian dinosaurs sitting atop nests in bird-like brooding positions, suggesting they incubated their eggs much as modern birds do. Oviraptor fossils discovered in this posture were initially misinterpreted as egg thieves (hence the name) but were later recognized as parents tending their nests. Many theropod dinosaurs laid their eggs in open nests rather than burying them like crocodiles, another behavioral trait shared with birds. Some species, like Citipati, arranged their eggs in circular patterns reminiscent of modern bird nests. These shared reproductive behaviors provide another line of evidence linking birds to their dinosaurian ancestors, showing continuity not just in anatomy but in complex life history traits.

Growth Patterns and Metabolism

The way dinosaurs grew and regulated their body temperature provides yet another connection to birds. Unlike most reptiles, which grow slowly throughout their lives, both birds and their dinosaur ancestors show evidence of rapid, determinate growth, reaching adult size relatively quickly and then stopping. Analysis of growth lines in dinosaur bones reveals that many species, particularly small theropods, grew at rates more similar to birds than to crocodiles or lizards. This rapid growth suggests elevated metabolic rates approaching the warm-blooded condition seen in modern birds. The presence of air sacs and highly efficient respiratory systems in both groups further supports this metabolic similarity. These physiological parallels complement the anatomical evidence, suggesting that key aspects of bird biology were already developing in their dinosaur ancestors.

Cladistic Analysis: The Family Tree

Modern classification methods based on shared derived characteristics (cladistics) consistently place birds within the theropod dinosaur group, specifically among maniraptoran dinosaurs. This classification isn’t merely academic—it reflects evolutionary reality, with birds representing the only dinosaur lineage to survive the end-Cretaceous extinction event. When scientists analyze hundreds of anatomical features across dinosaurs, birds, and other reptiles, the results invariably show birds nested within Dinosauria rather than as a separate group. Features once thought unique to birds, such as wishbones, three-fingered hands, and hollow bones, are now known to be widespread among theropod dinosaurs. Cladistic analysis demonstrates that the distinction between “bird” and “dinosaur” is largely artificial from an evolutionary perspective—birds simply represent the surviving branch of a once much larger dinosaur family tree.

The Skeptics’ Arguments

Despite overwhelming evidence, some researchers have historically questioned the dinosaurian origin of birds, proposing alternative evolutionary pathways. The most prominent alternative theory, championed by a small minority of scientists, suggests birds evolved from earlier archosaurian reptiles independently of dinosaurs. Proponents of this viewpoint point to features like the different finger development in embryonic birds compared to dinosaurs, though recent developmental studies have largely resolved these apparent discrepancies. Another objection involves the timing of bird origins relative to their supposed dinosaur ancestors—the “temporal paradox” argument suggesting some bird-like dinosaurs lived too late to be ancestral to birds. However, new fossil discoveries have repeatedly filled these gaps, and the current fossil record shows a clear temporal progression of increasingly bird-like dinosaurs leading to early birds. While healthy scientific skepticism drives further research, the weight of evidence strongly favors the dinosaurian origin of birds.

Convergent Evolution vs. Direct Ancestry

An important distinction in evolutionary biology is between homology (similarity due to shared ancestry) and analogy (similarity due to convergent evolution). Critics of the bird-dinosaur link have sometimes suggested that similarities between the groups might represent convergent evolution rather than direct ancestry. However, the sheer number of shared specialized features between birds and theropod dinosaurs makes convergent evolution extremely unlikely. These similarities include not just feathers but numerous skeletal features, egg structure, nesting behavior, and growth patterns. The progressive appearance of bird-like features across multiple dinosaur lineages forms a pattern consistent with shared ancestry rather than convergence. Furthermore, convergent evolution typically produces similar adaptations through different developmental pathways, whereas birds and dinosaurs share highly specific developmental patterns in structures like the wrist and hand, strongly suggesting homology rather than convergence.

Living Dinosaurs: Modern Birds

From a cladistic perspective, modern birds are living dinosaurs—specifically, they are highly specialized theropod dinosaurs that survived the mass extinction event 66 million years ago. This evolutionary heritage is evident in numerous aspects of bird biology, from their scale-covered legs (modified reptilian scales) to their toothless beaks (evolved from toothed ancestors) and even their behaviors like nest-building. The 10,000+ species of modern birds represent an extraordinary adaptive radiation from their dinosaurian ancestors, having evolved specialized adaptations for diverse ecological niches from the oceans to the highest mountains. Far from being merely related to dinosaurs, birds are dinosaurs in the same way that humans are mammals—they belong to the group by definition. This realization transforms our understanding of both groups: dinosaurs didn’t completely vanish 66 million years ago, and birds carry the evolutionary legacy of some of Earth’s most magnificent prehistoric creatures.

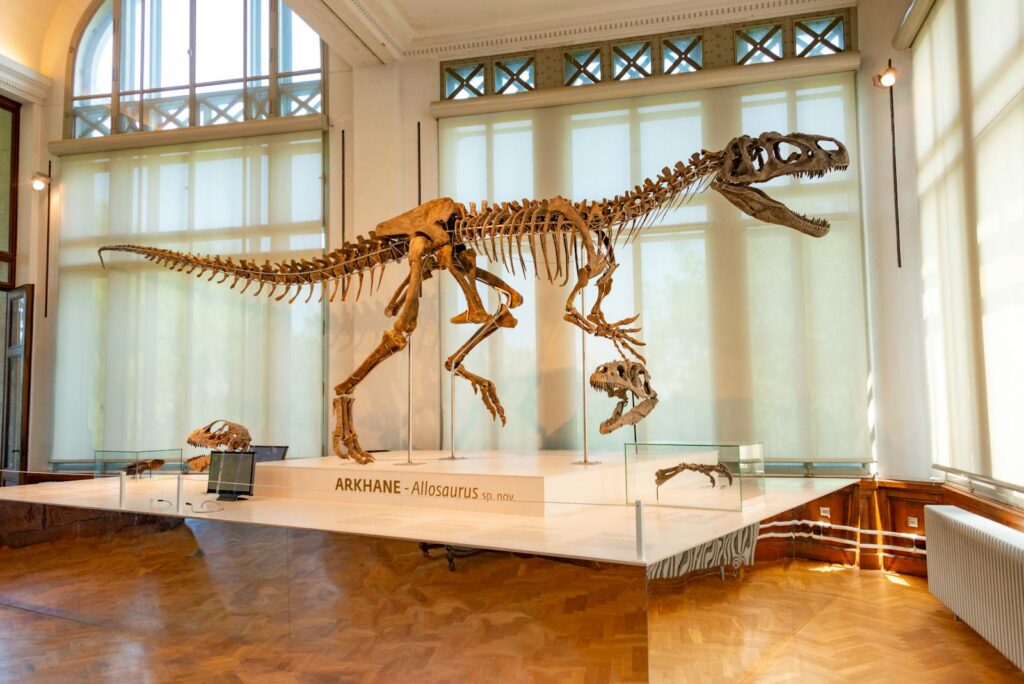

The Consensus View Today

The scientific consensus regarding birds as descendants of theropod dinosaurs has strengthened continuously since the 1970s, with each discovery adding support to this relationship. Modern paleontological textbooks, museum exhibits, and research papers operate within this paradigm, reflecting its acceptance across the scientific community. While healthy debate continues about specific details—such as which particular dinosaur group gave rise to birds and exactly how flight evolved—the fundamental connection between birds and dinosaurs is no longer seriously questioned in mainstream paleontology. This represents a remarkable scientific journey from the initial proposal of the bird-dinosaur link by Thomas Henry Huxley in the 1860s, through decades of skepticism, to the current robust consensus built on multiple independent lines of evidence. The transformation in our understanding demonstrates science at its best: a gradual refinement of knowledge through accumulating evidence, leading to a profound shift in how we view evolutionary relationships.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while feathers provide compelling evidence for the dinosaurian origin of birds, they represent just one thread in a rich tapestry of evidence. The combination of skeletal anatomy, growth patterns, behavior, molecular data, and increasingly detailed fossil discoveries collectively establishes birds as living dinosaurs beyond reasonable scientific doubt. This evolutionary connection doesn’t diminish either group but enriches our understanding of both: dinosaurs were more diverse, dynamic, and bird-like than traditionally portrayed, while birds inherit a profound evolutionary legacy stretching back over 150 million years. Rather than feathers being the final proof, they are perhaps better understood as the most visually striking element of a comprehensive case built on multiple scientific disciplines. The next time you watch a sparrow or eagle, remember you’re observing not just a bird, but a living dinosaur—the successful survivor of an ancient lineage that continues to thrive in our modern world.