The dawn of the dinosaur era wasn’t marked by the immediate dominance of these fascinating creatures. Contrary to popular imagination, early dinosaurs were not the towering behemoths we often envision when thinking of species like Tyrannosaurus rex or Brachiosaurus. Instead, the first dinosaurs were relatively small, nimble creatures that evolved during the Late Triassic period approximately 230 million years ago. At this time, Earth’s landscapes were dominated by diverse reptilian groups, many of which were larger and more established than the emerging dinosaur lineages. This article explores how early dinosaurs’ smaller size paradoxically became their greatest advantage, allowing them to survive, adapt, and eventually dominate Earth’s ecosystems for over 160 million years.

The Triassic Landscape: A Competitive Arena

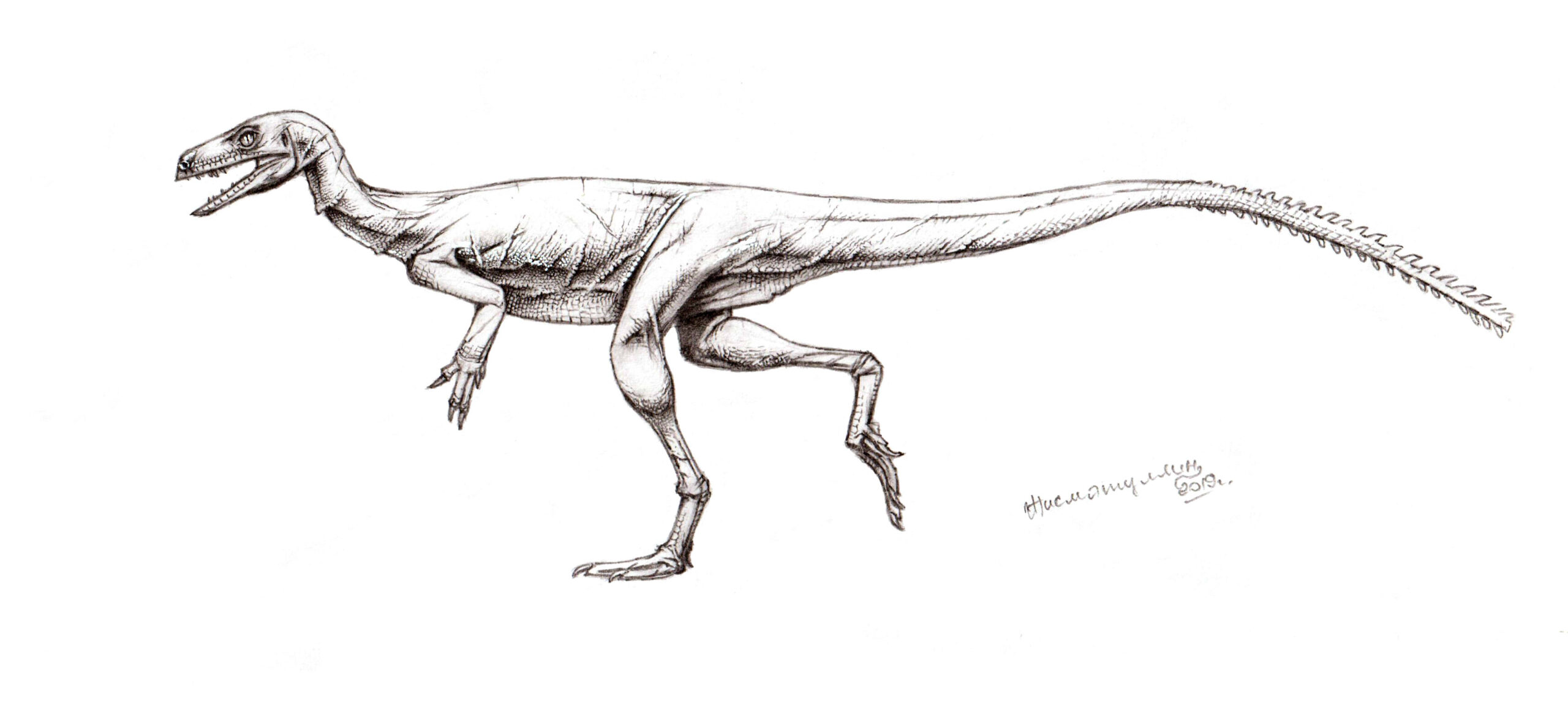

When dinosaurs first appeared during the Late Triassic period, they entered an already crowded ecological stage. The landscape was dominated by various archosaurs (the larger group that includes crocodilians, pterosaurs, and dinosaurs), massive amphibians, and early mammal relatives. Particularly prominent were the pseudosuchians (crocodile-line archosaurs) like rauisuchians and phytosaurs, which occupied many of the top predator niches. Early dinosaurs like Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus, measuring just 1-3 meters in length, were far from being apex predators. They existed in a world where competition for resources was fierce, and larger reptiles had already established dominance in many ecological niches. This challenging environment required innovative adaptations for survival, and the early dinosaurs’ relatively small size would prove to be a crucial advantage rather than a limitation.

Evolutionary Origins: Starting Small

Dinosaurs evolved from small, bipedal archosaurs known as dinosauromorphs. Fossil evidence suggests that these early dinosaur ancestors were modest in size, with most species weighing less than 15 kilograms. This small stature was inherited by the earliest true dinosaurs, which emerged around 230-245 million years ago. Paleontological discoveries in Argentina, Brazil, and Madagascar have unearthed fossils of these primitive dinosaurs, showing they were generally lightweight and agile. Their diminutive size wasn’t a disadvantage but rather a starting point that allowed for specific adaptations. Early dinosaurs like Eoraptor lunensis stood just about knee-high to an adult human and weighed approximately 10-15 kilograms. This modest beginning enabled dinosaurs to occupy ecological niches that were unavailable to larger reptiles, effectively laying the groundwork for their later diversification and success.

Metabolic Advantages: The Efficiency Factor

One of the most significant advantages that early dinosaurs possessed was their enhanced metabolic efficiency. Research indicates that early dinosaurs likely had higher metabolic rates than their reptilian contemporaries, falling somewhere between modern reptiles and birds. This elevated metabolism provided them with greater energy for sustained activity, faster growth rates, and improved cold tolerance. For small-bodied animals, these metabolic advantages were particularly beneficial, as they could maintain activity levels and body temperatures more effectively than larger animals with similar metabolisms. Evidence from bone histology (studying the microscopic structure of fossilized bone) reveals that early dinosaurs grew faster than other reptiles of similar size. This metabolic edge allowed early dinosaurs to be more active hunters or foragers, potentially giving them an advantage during times of resource scarcity when energy-efficient bodies were critical for survival.

Bipedalism: Running on Two Legs

Perhaps the most visually distinctive adaptation of early dinosaurs was their bipedal stance—the ability to walk and run efficiently on two legs. While some other Triassic reptiles could occasionally move bipedally, early dinosaurs evolved specialized anatomical features that made this their primary mode of locomotion. Their hind limbs were positioned directly beneath their bodies rather than splayed to the sides like most reptiles, creating a more energy-efficient posture. This bipedal adaptation offered several advantages to small dinosaurs. First, it increased their running speed, making them more effective both as predators and at escaping larger predators. Second, it freed their forelimbs for other specialized functions such as grasping prey or manipulating objects. Third, bipedalism raised their heads higher off the ground, potentially improving their field of vision for spotting both predators and prey. For small creatures in a world of giants, these mobility advantages were crucial survival tools.

Dietary Flexibility: Opportunistic Feeding

Early dinosaurs displayed remarkable dietary flexibility, which proved vital in their competitive environment. Paleontological evidence suggests that many early dinosaurs were omnivorous, capable of consuming both plant material and small animals depending on availability. This dietary adaptability allowed them to exploit food resources that might be overlooked by more specialized reptiles. For instance, Eoraptor shows dentition suggesting an omnivorous diet, with different tooth types appropriate for various food sources. Being small actually enhanced this dietary flexibility, as smaller animals generally require less food in absolute terms and can survive on more marginal resources. During times of environmental stress or seasonal scarcity, this ability to switch between food sources would have been particularly advantageous. Additionally, smaller gut volumes mean faster digestion cycles, allowing early dinosaurs to process food more efficiently than many of their larger contemporaries.

Ecological Niches: Finding Room in a Crowded World

The smaller size of early dinosaurs allowed them to exploit ecological niches that were either unoccupied or underutilized by larger reptiles. These “peripheral” niches often existed in habitats that were challenging for larger animals to access or efficiently utilize. For example, early dinosaurs could venture into denser vegetation, climb inclines, or navigate rough terrain more easily than bulkier contemporaries. Their size also made them better suited to exploit microhabitats – small, localized environments with specific conditions. Fossil evidence from localities like the Ischigualasto Formation in Argentina shows that early dinosaurs often coexisted with larger predators by occupying different ecological roles. This niche partitioning reduced direct competition and allowed dinosaurs to establish themselves in the ecosystem without directly challenging larger, more established reptiles. By starting in these peripheral niches, dinosaurs established evolutionary footholds from which they could later expand as conditions changed.

Reproductive Strategy: The Egg Advantage

Early dinosaurs likely possessed reproductive strategies that gave them advantages over many contemporaneous reptiles. Although direct evidence of the earliest dinosaur eggs is limited, later dinosaur reproductive biology suggests they laid amniotic eggs with protective shells, similar to but more advanced than those of other reptiles. Smaller body size correlates with reaching sexual maturity earlier and potentially producing more generations in a shorter time span, allowing for faster population growth and recovery after environmental disturbances. Additionally, smaller dinosaurs likely produced smaller clutches of eggs that required less investment of bodily resources per reproductive cycle, enabling more frequent breeding. This reproductive efficiency would have been particularly advantageous during the unstable climate conditions of the Late Triassic period. Furthermore, evidence suggests dinosaurs may have exhibited parental care earlier in their evolutionary history than many other reptile groups, increasing offspring survival rates and providing another competitive edge in their reproductive strategy.

Surviving Extinction Events: Size as a Buffer

The Late Triassic period witnessed several extinction events that significantly reshaped terrestrial ecosystems. The most notable was the end-Triassic extinction approximately 201 million years ago, which eliminated many competing reptile groups but spared most dinosaur lineages. Smaller animals often have advantages during extinction events for several reasons. They typically require less food in absolute terms, can hide in sheltered microhabitats, and their populations can recover more quickly due to shorter generation times. Additionally, smaller animals with higher metabolic rates can often better regulate their internal conditions during environmental stress. Evidence suggests that the end-Triassic extinction was likely triggered by massive volcanic eruptions associated with the breakup of Pangaea, causing climate disruption and environmental instability. While many larger reptile groups suffered severely or went extinct during these events, dinosaurs survived and subsequently expanded into newly vacant ecological niches, setting the stage for their Jurassic radiation and dominance.

Adaptability: Small Bodies, Flexible Responses

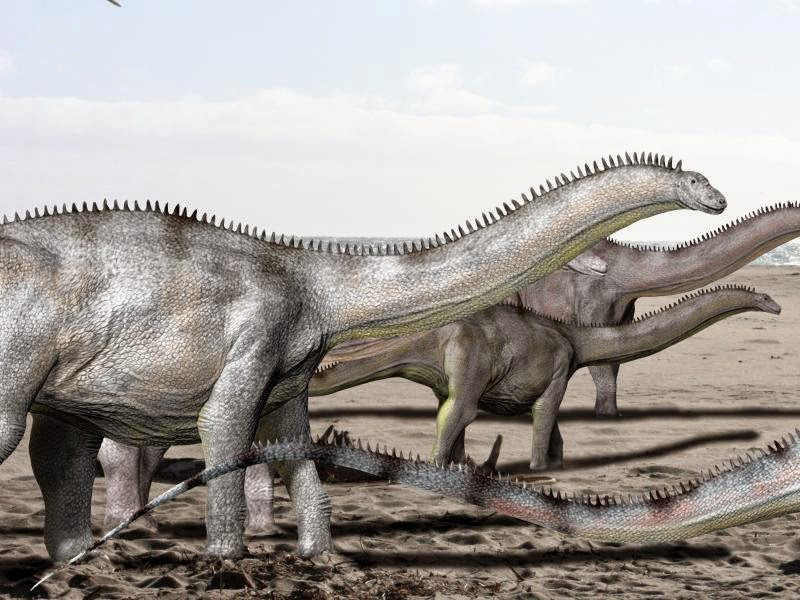

Smaller body size generally correlates with greater adaptability to changing environmental conditions. Early dinosaurs demonstrated remarkable evolutionary plasticity, allowing them to adjust to the dynamic environments of the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods. Smaller animals typically have shorter generation times, which accelerates the pace of natural selection and allows more rapid evolutionary responses to environmental changes. This adaptability is evident in the fossil record, where we see early dinosaurs quickly diversifying into various ecological roles. For example, within a relatively short geological timespan, dinosaurs evolved from primarily small, bipedal forms into a range of body plans including the earliest sauropodomorphs (predecessors to the giant long-necked dinosaurs). Their small initial size meant that early dinosaurs had more potential evolutionary directions available to them, as it’s generally easier to evolve larger body sizes from smaller ancestors than vice versa, giving them greater evolutionary flexibility as conditions changed throughout the Mesozoic Era.

Energy Efficiency: Less Food, More Action

Smaller dinosaurs possessed significant advantages in energy efficiency compared to larger reptiles. The relationship between body size and energy requirements is not linear—smaller animals have higher metabolic rates per unit of body mass but require less total energy than larger animals. This scaling relationship meant that early dinosaurs could maintain active lifestyles while consuming proportionally less food than larger reptiles. Their enhanced metabolic efficiency, combined with bipedal locomotion, created a more energy-efficient body plan that could extract maximum activity from minimal resources. Paleontological evidence suggests that early dinosaurs had relatively large brains for their body size compared to many contemporary reptiles, indicating potentially more complex behaviors and better neural control of their movements. This neurological efficiency, combined with their metabolic advantages, allowed early dinosaurs to be more active and responsive with less energetic input, a crucial advantage in the competitive Triassic ecosystems where resources were often limited or unpredictable.

Thermal Regulation: Staying Active Longer

Small body size provided early dinosaurs with advantages in thermal regulation that larger reptiles lacked. Smaller animals have a higher surface-area-to-volume ratio, allowing them to gain or lose heat more rapidly as needed. This thermal responsiveness, combined with evidence suggesting dinosaurs had enhanced metabolic rates, likely enabled them to maintain more stable internal temperatures and remain active for longer periods than many contemporary reptiles. Recent research on dinosaur bone histology shows growth patterns suggesting that even early dinosaurs may have had some degree of endothermy (warm-bloodedness) or at least elevated metabolic rates compared to typical reptiles. This thermal advantage would have been particularly beneficial during the climatic fluctuations of the Late Triassic period, allowing dinosaurs to remain active during cooler periods when other reptiles might become sluggish. Additionally, being active during cooler parts of the day or year would have given dinosaurs access to temporal niches unavailable to more thermally constrained reptiles, effectively expanding their ecological opportunities.

Predator Avoidance: The Benefits of Being Small

In the dangerous Triassic landscapes populated by numerous large predators, the modest size of early dinosaurs offered significant advantages for predator avoidance. Their smaller stature allowed them to utilize hiding places inaccessible to larger animals, seek shelter in burrows or dense vegetation, and generally maintain lower profiles in the environment. Early dinosaurs’ enhanced speed and agility, products of their bipedal stance and possibly higher metabolic rates, provided effective escape mechanisms when confronted by larger predators. The fossil record indicates that contemporaneous apex predators included massive rauisuchians and other crurotarsans that, while powerful, likely lacked the agility of the smaller dinosaurs. Evidence from trackways suggests early dinosaurs were capable of rapid direction changes and bursts of speed that would have made them challenging prey to capture. Additionally, smaller animals are generally more cryptic (difficult to detect) in their environments, and early dinosaurs likely possessed coloration and behaviors that enhanced their ability to avoid detection in the first place—a classic example of “hiding in plain sight” that their larger relatives could not achieve.

The Evolutionary Trajectory: From Small Beginnings to Global Dominance

The small size of early dinosaurs positioned them perfectly for the evolutionary trajectory that would eventually lead to their dominance of terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years. Beginning with modest-sized species, dinosaurs gradually diversified and expanded into numerous ecological niches throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Their initial small size provided evolutionary plasticity that allowed for spectacular diversification, from the massive sauropods to the agile theropods and armored ornithischians. Importantly, not all dinosaur lineages evolved toward gigantism—many successful groups maintained relatively small body sizes throughout their evolutionary history, particularly among the theropod dinosaurs that would eventually give rise to birds. This pattern demonstrates that the advantages of smaller size remained relevant even as some dinosaur lineages explored the limits of terrestrial body size. The persistence of smaller-bodied dinosaur lineages alongside their gigantic relatives highlights how the initial advantages of modest size continued to provide evolutionary benefits even as dinosaurs came to dominate Earth’s ecosystems. This evolutionary journey, beginning with small, nimble creatures and leading to one of the most successful vertebrate radiations in Earth’s history, underscores how a seeming limitation—small size in a world of giants—proved to be the foundation for extraordinary evolutionary success.

Lessons from the Past: Understanding Evolutionary Success

The story of early dinosaurs offers valuable insights into evolutionary processes and the complex factors that determine which groups thrive and which fade away. Contrary to intuitive assumptions that bigger is always better in evolutionary terms, the success of early dinosaurs demonstrates that initial constraints can become advantages under the right circumstances. Their story challenges the common misconception that dinosaurs were immediately dominant upon their appearance, showing instead that evolutionary success often begins with modest foundations and opportunistic exploitation of available niches. The gradual ascendance of dinosaurs from small, peripheral players to ecosystem dominants provides an important case study in how evolutionary transitions occur. This pattern of “starting small” has parallels in other major evolutionary radiations, including the rise of mammals after the dinosaur extinction and even the emergence of humans from relatively small-bodied primate ancestors. The dinosaur story reminds us that evolutionary success isn’t always about immediate dominance but can involve prolonged periods of peripheral existence before conditions align to favor explosive diversification. In studying how these small early dinosaurs navigated their reptile-dominated world, paleontologists gain crucial insights into the dynamics of evolution, extinction, and the unpredictable pathways that shape life’s history on Earth.

Conclusion

Early dinosaurs’ story teaches us that in evolution, apparent limitations can become powerful advantages. Beginning as small creatures in a world dominated by larger reptiles, these pioneers leveraged their size through enhanced metabolism, efficient bipedal locomotion, and remarkable adaptability. These advantages allowed them to survive extinction events that eliminated many competitors and set the stage for dinosaurs’ subsequent dominance. From these modest beginnings emerged one of the most successful vertebrate groups in Earth’s history, ruling terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years and eventually giving rise to modern birds. The evolutionary journey of dinosaurs reminds us that success often comes not from overwhelming strength or size at the outset, but from adaptations that provide resilience through changing conditions—a lesson from deep time that resonates with many biological success stories throughout Earth’s history.