The Ice Age, a period spanning from approximately 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago, was home to some of the most impressive megafauna ever to walk the Earth. While woolly mammoths often dominate our cultural imagination of this era, they were far from the most formidable creatures of their time. The Pleistocene epoch showcased an extraordinary array of gigantic mammals and reptiles that would dwarf many of our modern animals in size, strength, and sometimes ferocity. These magnificent beasts evolved remarkable adaptations to survive in harsh glacial conditions, creating a prehistoric world that would seem almost alien to us today. In this exploration, we’ll venture beyond the familiar mammoth to discover seven Ice Age giants whose immense proportions and impressive capabilities made even these iconic tusked elephants seem relatively tame by comparison.

Megatherium: The Giant Ground Sloth

Standing up to 20 feet tall on its hind legs and weighing approximately 4 tons, Megatherium was an absolutely colossal relative of today’s tree sloths. Unlike its modern descendants, this giant ground sloth was a ground-dwelling herbivore with massive claws that weren’t used for climbing but instead for pulling down branches and defending against predators. Megatherium possessed tremendous strength in its forelimbs, allowing it to tear apart vegetation and potentially ward off even the fiercest Ice Age predators. What makes this creature particularly impressive is the stark contrast to modern sloths – while today’s species are small and slow-moving tree-dwellers, Megatherium was a ground-based giant that could rear up on its powerful hind legs to reach vegetation at heights comparable to a modern giraffe. Scientists believe these creatures were primarily found across South America until their extinction approximately 10,000 years ago, potentially due to human hunting and habitat changes at the end of the last ice age.

Glyptodon: The Volkswagen-Sized Armadillo

Imagine an armadillo the size of a small car, and you’ve got the Glyptodon, an ancient relative of modern armadillos that grew to around 10 feet in length and weighed up to 2 tons. This massive creature possessed a domed carapace made of bony plates that provided exceptional protection against the formidable predators of the time. Unlike modern armadillos, Glyptodon couldn’t roll into a ball; instead, its armor was rigidly fixed, creating a tank-like appearance that would have been virtually impenetrable to most attackers. Some species even possessed spiked tail clubs that could deliver devastating blows to potential threats. Glyptodons were herbivores that grazed across the grasslands of South America, using their small, peg-like teeth to process vegetation. Archaeological evidence suggests that early humans occasionally used the massive shells of deceased Glyptodons as shelters, providing a fascinating glimpse into how these impressive creatures interacted with our ancestors before their extinction approximately 10,000 years ago.

Arctodus: The Short-Faced Bear

Arctodus, commonly known as the short-faced bear, was the most terrifying predator of Ice Age North America, dwarfing even the largest modern bears in size and predatory capability. Standing over 11 feet tall when reared on its hind legs and weighing up to 2,200 pounds, this massive carnivore possessed proportionally longer legs than modern bears, suggesting it was capable of sustained running at speeds possibly reaching 40 mph. Its skull and jaw structure indicates one of the most powerful bite forces in mammalian history, easily capable of crushing bones to access nutritious marrow. The bear’s common name comes from its relatively flat face with eyes set far apart, giving it excellent vision for hunting across the open Ice Age landscapes. Despite being primarily carnivorous, evidence suggests Arctodus was an opportunistic omnivore that could also consume plant material when necessary. The short-faced bear’s reign of terror ended approximately 11,000 years ago, likely due to the extinction of many of its prey species and competition with humans who were expanding across North America.

Megaloceros: The Irish Elk

Despite its common name suggesting it was exclusive to Ireland, Megaloceros giganteus—commonly known as the Irish Elk—roamed across Europe, Asia, and North Africa during the Ice Age. This magnificent deer species boasted the largest antlers of any known deer, measuring up to 12 feet across and weighing up to 88 pounds. These enormous antlers weren’t just for show; they served as powerful visual signals of genetic fitness to potential mates, with larger antlers indicating stronger, more desirable males. Standing around 7 feet tall at the shoulder and weighing up to 1,500 pounds, Megaloceros was significantly larger than any modern deer species. The incredible weight of their antlers required extremely powerful neck muscles and specialized adaptations in their spine and shoulders. Interestingly, the Irish Elk’s extinction around 7,700 years ago may have been partially influenced by their spectacular antlers—as forests replaced open grasslands at the end of the Ice Age, the massive headgear would have become increasingly disadvantageous in wooded environments, potentially contributing to their decline alongside human hunting pressure.

Smilodon: The Saber-Toothed Cat

Smilodon, often called the saber-toothed tiger (although not closely related to modern tigers), was one of the most specialized and fearsome predators of the Ice Age. Its most distinctive feature was, of course, its elongated canine teeth, which could grow up to 11 inches in length and were designed for delivering precise, lethal strikes to prey. Unlike modern big cats that kill with a suffocating throat bite, Smilodon used its immensely powerful forelimbs—built with muscles stronger than any modern cat—to pin down prey before delivering a devastating bite to the throat or abdomen with its specialized teeth. The largest species, Smilodon populator, weighed up to 900 pounds, making it significantly heavier than modern lions or tigers. Fossil evidence shows that these predators often suffered serious injuries during hunts but survived long enough for bones to heal, suggesting they lived in social groups where other members provided food for injured individuals. Their extinction approximately 10,000 years ago likely resulted from the disappearance of their large herbivore prey as the Ice Age ended, demonstrating how highly specialized predators can be particularly vulnerable to ecosystem changes.

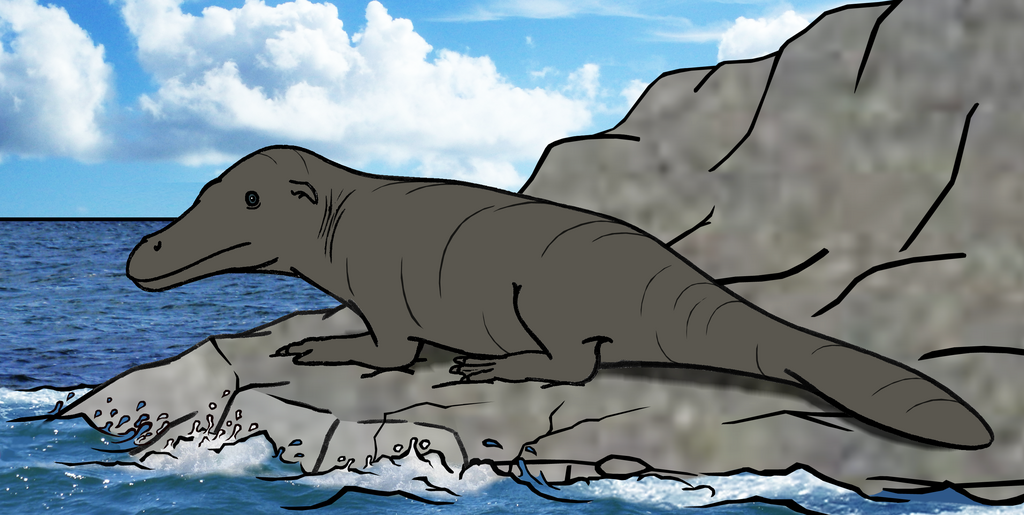

Titanoboa: The Monster Snake

Though technically predating the Ice Age proper and thriving during the Paleocene epoch (about 60 million years ago), Titanoboa deserves mention as a giant that makes even the largest Ice Age creatures seem modest. This colossal snake reached lengths of approximately 42 feet and weighed up to 2,500 pounds, making it the largest snake ever discovered and dwarfing today’s reticulated pythons and anacondas. Fossil evidence from Colombia suggests Titanoboa was a constrictor that hunted in warm, tropical environments, likely preying on large fish, crocodilians, and possibly other vertebrates. Scientists have calculated that maintaining its massive body would have required ambient temperatures much higher than today’s tropics, providing valuable insights into ancient climate conditions. The snake’s vertebrae were astonishingly large, each approximately the size of a grapefruit, indicating the tremendous muscle mass needed to move its enormous body. While Titanoboa didn’t coexist with mammoths, its inclusion highlights the incredible diversity of megafauna that Earth has supported through different geological periods, showcasing evolution’s capacity to produce truly monumental creatures when conditions permit.

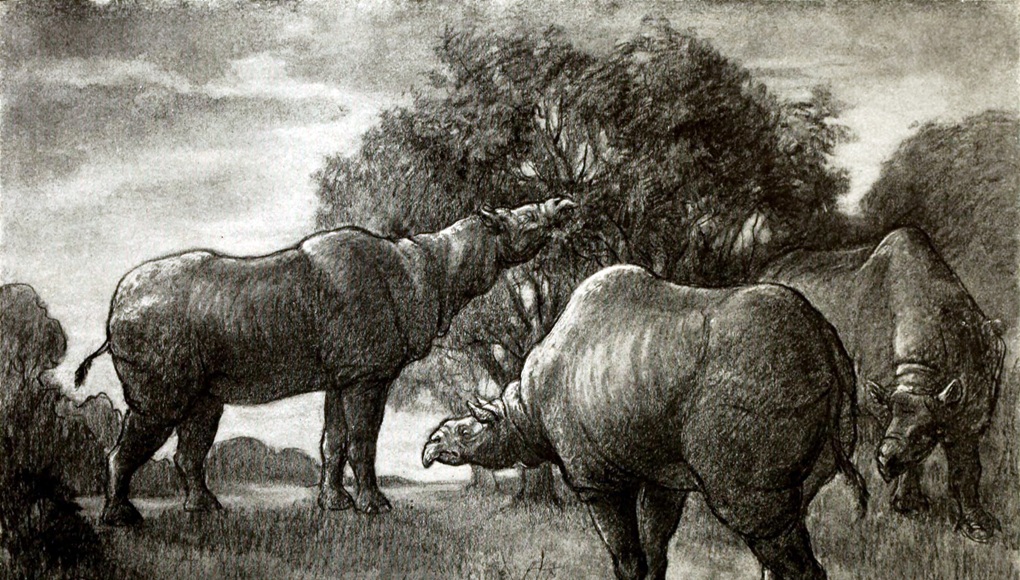

Paraceratherium: The Largest Land Mammal Ever

Paraceratherium, previously known as Indricotherium or Baluchitherium, holds the distinction of being the largest land mammal ever to walk the Earth, making even the largest mammoths look modest by comparison. This distant relative of modern rhinoceroses stood up to 18 feet tall at the shoulder, measured approximately 26 feet in length, and weighed an estimated 15 to 20 tons—about the weight of three or four modern African elephants combined. Unlike its armored rhinoceros relatives today, Paraceratherium lacked horns and instead possessed a long, flexible neck and specialized teeth adapted for browsing on treetop vegetation, somewhat similar to modern giraffes in ecological niche. These giants roamed across Asia during the Oligocene period (34-23 million years ago), preceding the traditional Ice Age but representing an important evolutionary milestone in mammalian gigantism. Their impressive size likely provided protection from most predators, though young or weakened individuals may have fallen prey to pack-hunting carnivores. Paraceratherium’s extinction appears linked to climate change that transformed their woodland habitats into more open grasslands, eliminating their specialized browsing niche.

The Mighty Mammoth: Setting the Baseline

Before exploring creatures that dwarf mammoths, it’s worth establishing just how impressive these iconic Ice Age proboscideans actually were. The woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) stood around 11 feet tall at the shoulder and weighed up to 6 tons, making it comparable to modern African elephants but with distinctive adaptations for cold weather. Their most notable features were their massive curved tusks, which could reach lengths of up to 15 feet and weigh 200 pounds each, serving multiple purposes from clearing snow to fighting for mating rights. Dense woolly coats consisting of outer guard hairs up to 3 feet long and a thick undercoat provided insulation against bitter Arctic temperatures, while a fatty hump on their shoulders stored energy reserves for harsh winters. Small ears and tails minimized heat loss in their frigid habitat, demonstrating remarkable cold-climate adaptations. Despite their impressive size and evolutionary success—surviving for hundreds of thousands of years—woolly mammoths disappeared from most of their range by about 10,000 years ago, with the last isolated population persisting on Wrangel Island until about 4,000 years ago, making them contemporaries of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Elasmotherium: The Siberian Unicorn

Elasmotherium, often called the Siberian unicorn, was a massive rhinoceros species that bore little resemblance to its modern relatives. Standing approximately 6 feet tall at the shoulder, measuring 15 feet in length, and weighing up to 4.5 tons, this imposing herbivore featured a single massive horn on its forehead that could potentially reach lengths of up to 6 feet. Unlike the horns of modern rhinoceroses, which are composed of compressed keratin fibers, Elasmotherium’s horn was likely structurally different, possibly containing a bony core that supported an even larger keratin structure. The creature’s specialized teeth indicated it was a dedicated grazer adapted to consuming tough grassland vegetation across the Eurasian steppe. Particularly interesting is how recently this “unicorn” survived—while previously thought to have gone extinct around 200,000 years ago, recent fossil evidence suggests some populations may have persisted until roughly 35,000-36,000 years ago, meaning they would have encountered and potentially been hunted by early humans. The imposing size, unusual horn configuration, and specialized grazing adaptations made Elasmotherium a truly unique Ice Age giant that would have been an impressive sight across the ancient Eurasian plains.

Gigantopithecus: The Real King Kong

Standing up to 10 feet tall and weighing potentially over 1,000 pounds, Gigantopithecus blacki represents the largest primate ever known, dwarfing even the largest gorillas. This enormous ape roamed the forests of what is now southern China and Southeast Asia from about two million to as recently as 300,000 years ago, making it a contemporary of both ancient human species and the Ice Age megafauna. Fossil evidence is limited primarily to jawbones and teeth, requiring scientists to make educated estimates about its full appearance, but the massive dental remains indicate a specialized herbivorous diet likely consisting of tough vegetation, fruits, and possibly bamboo. Despite popular culture sometimes depicting Gigantopithecus as a bipedal, King Kong-like figure, most scientific reconstructions suggest it moved on all fours similar to modern gorillas, with knuckle-walking locomotion supporting its tremendous weight. Intriguingly, Gigantopithecus existed alongside early human relatives like Homo erectus, raising fascinating questions about potential interactions between these species. The enormous ape’s extinction approximately 300,000 years ago likely resulted from a combination of climate change affecting forest habitats, specialized dietary requirements, and possibly competition with other primates including early humans.

Deinosuchus: The Terror Crocodile

While predating the traditional Ice Age by millions of years, Deinosuchus deserves mention as one of the most terrifying predators in Earth’s history, existing during the Late Cretaceous period approximately 82 to 73 million years ago. This “terrible crocodile” reached lengths of up to 40 feet and weighed an estimated 8 to 10 tons, making it one of the largest crocodilians ever to exist and dwarfing even the largest modern saltwater crocodiles. With a skull measuring nearly 6 feet long and equipped with teeth the size of bananas, Deinosuchus was capable of preying on dinosaurs, as evidenced by fossilized bite marks found on dinosaur bones. Unlike many other prehistoric giants that were specialized for particular ecological niches, Deinosuchus employed the same basic ambush predator strategy used by modern crocodilians, lying in wait at water’s edge before launching devastating attacks on unsuspecting prey. Fossil remains have been found primarily in what is now the southern United States and northern Mexico, indicating these massive predators inhabited coastal environments along the Western Interior Seaway that once divided North America. While not contemporaneous with mammoths or other traditional Ice Age fauna, Deinosuchus represents the pinnacle of crocodilian evolution and serves as a reminder that Earth has produced absolutely massive predators throughout different geological eras.

The Ecological Impact of Ice Age Giants

The megafauna of the Ice Age weren’t just impressive in size—they were ecosystem engineers that fundamentally shaped their environments in ways that still influence our world today. Large herbivores like mammoths, ground sloths, and giant rhinoceroses maintained grassland ecosystems through their grazing activities, preventing forest encroachment and creating mosaic landscapes that supported tremendous biodiversity. Their massive bodies transported nutrients across landscapes through dung deposition, while their movements created trails used by other animals and even early humans. After death, their enormous carcasses provided critical food resources for scavengers and decomposers, creating temporary hotspots of biodiversity. The presence of these herbivores supported populations of specialized mega-predators like short-faced bears and saber-toothed cats, creating complex predator-prey dynamics that drove evolutionary adaptations on both sides. Perhaps most significantly, the relatively recent extinction of these megafauna—many disappearing just 10,000-12,000 years ago—has left ecological vacancies that still exist in modern ecosystems, with some scientists proposing “rewilding” projects using modern analogs to restore ecological functions once performed by these Ice Age giants. Understanding these ancient ecological relationships provides valuable insights for modern conservation biology and ecosystem management.

Why These Giants Disappeared

The extinction of Ice Age megafauna represents one of paleontology’s most enduring debates, with evidence pointing to a complex interplay of factors rather than a single cause. Climate change at the end of the Pleistocene created rapid habitat transformations that many specialized megafauna couldn’t adapt to quickly enough, with warming temperatures and changing precipitation patterns altering vegetation communities these animals depended upon. Simultaneously, the global expansion of human populations introduced a novel and highly effective predator into ecosystems where large animals had evolved without human hunting pressure. The “overkill hypothesis” suggests that even relatively small human populations could have devastating impacts on megafauna that reproduced slowly and had low population densities. Disease may have played an additional role, potentially introduced by humans or their domesticated animals as they expanded into new territories. Most modern scientists favor a “synergistic” model where climate change stressed megafauna populations while making them more vulnerable to human hunting pressure—neither factor alone being sufficient to cause complete extinction but becoming devastating in combination. Understanding these extinction mechanisms carries profound implications for modern conservation, as today’s remaining megafauna face similar combined threats from habitat loss, climate change, and human exploitation.