The commercial trade of dinosaur fossils has become one of paleontology’s most contentious issues, creating deep divisions between scientists, commercial collectors, auction houses, and governments worldwide. While some view fossil sales as an essential funding mechanism for new discoveries, others see it as a dangerous practice that places scientific treasures in private hands where they may be lost to research forever. With multi-million dollar dinosaur skeletons regularly appearing at high-profile auctions, the controversy continues to intensify rather than resolve. This ongoing tension reflects fundamental questions about who should own the prehistoric past and how we balance scientific knowledge with commercial interests.

The Historical Context of Fossil Collection

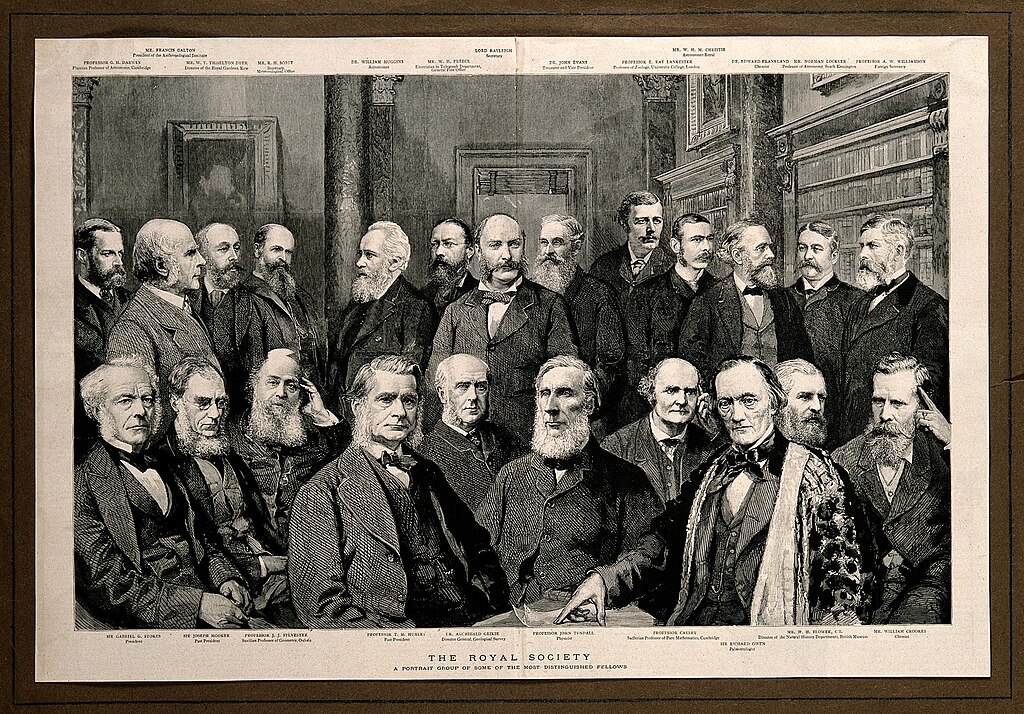

Dinosaur fossil collection has evolved dramatically since the 1800s when it began as a largely unregulated frontier pursuit. The infamous “Bone Wars” between paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope exemplified the early competitive and sometimes unethical practices in fossil hunting, with both men destroying fossils to prevent their rival from accessing them. Throughout most of the 20th century, dinosaur remains were primarily collected by academic institutions and museums for scientific study and public display. However, the 1990s marked a significant shift when commercial fossil hunting became increasingly lucrative, epitomized by the 1997 sale of the T. rex specimen “Sue” for $8.36 million to Chicago’s Field Museum. This watershed moment demonstrated the enormous financial value of dinosaur remains and forever changed the landscape of fossil collection and ownership.

The Scientific Community’s Perspective

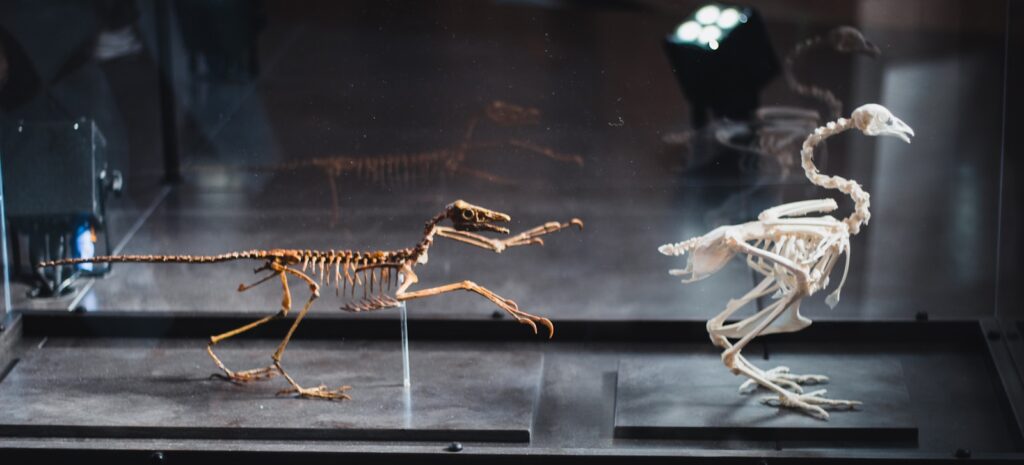

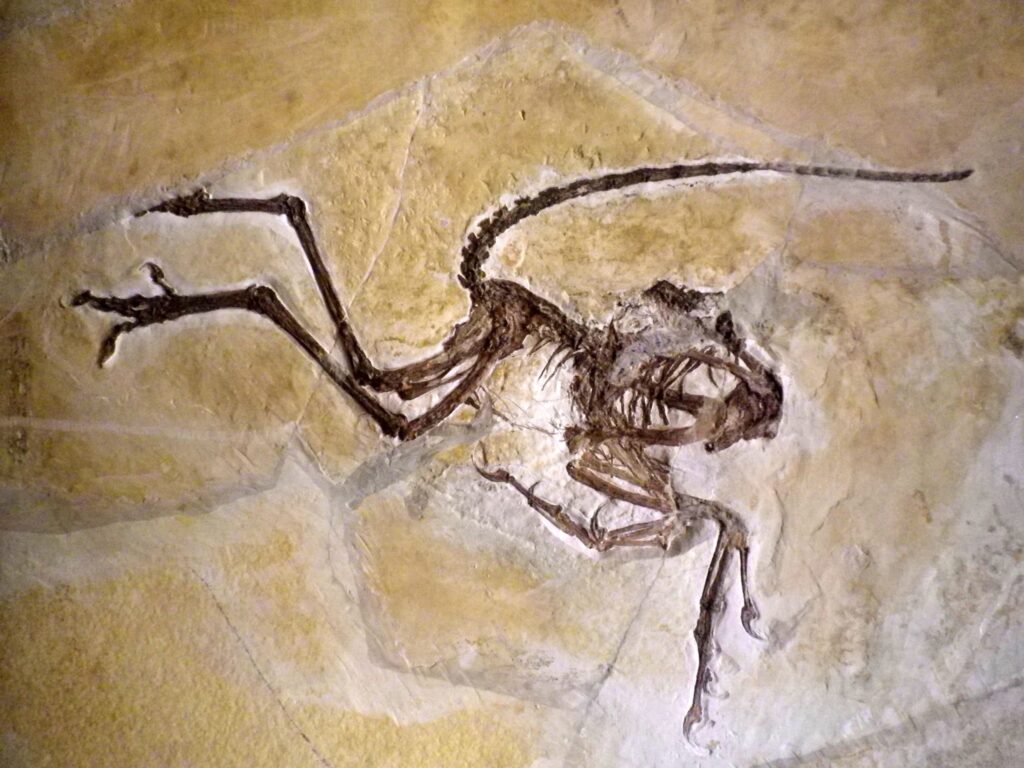

The majority of paleontologists and research institutions stand firmly against the commercial sale of significant dinosaur fossils. Their primary concern centers on the loss of crucial scientific data when specimens disappear into private collections without proper documentation or access for researchers. The scientific process requires peer review and replication, which becomes impossible when fossils are unavailable for study. Many paleontologists argue that unique fossils represent irreplaceable data points in understanding Earth’s biological history and should be considered part of humanity’s collective heritage rather than luxury commodities. Professional organizations like the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology have taken strong positions against commercial fossil sales, especially when specimens originate from public lands or might represent new species. These scientists maintain that proper scientific protocols during excavation are critical to preserving contextual information that commercial collectors might ignore in favor of extracting visually impressive specimens quickly.

The Commercial Collector’s Argument

Commercial fossil hunters and dealers present a different perspective, asserting that their work actually saves many specimens that might otherwise erode away unnoticed. They point out that academic institutions have limited resources for fieldwork, while commercial collectors can invest significantly in exploration, often discovering fossils that might never be found by scientific expeditions. Many commercial collectors maintain that they follow proper documentation protocols and frequently collaborate with scientists to ensure important specimens reach museums. They also highlight that private funding through fossil sales has financed numerous important discoveries that have advanced paleontological knowledge. Some dealers have established relationships with museums, offering them first right of refusal on significant specimens before they go to auction. The commercial sector argues that without financial incentives, many fossils would remain undiscovered, and the field of paleontology would progress much more slowly.

Legal Frameworks Across Different Countries

The regulation of fossil collection and sales varies dramatically worldwide, creating a complex international landscape. Mongolia and China maintain some of the strictest laws, declaring all fossils national property that cannot be exported or sold privately. The United States has a more nuanced approach, where fossils found on private land generally belong to the landowner who can sell them legally, while those discovered on federal lands are protected government property. Countries like Canada, Australia, and Argentina have implemented various forms of heritage protection laws that restrict export of significant specimens but may allow certain commercial activities domestically. This patchwork of regulations creates significant challenges for enforcement and has led to numerous high-profile legal battles over smuggled specimens. The 2012 case of a Tarbosaurus bataar (an Asian relative of T. rex) that was repatriated to Mongolia after being illegally exported and nearly sold at auction in New York highlighted these international tensions and legal complications.

The Ethics of Ownership

Beyond legal considerations, the fossil trade raises profound ethical questions about who should rightfully own objects that represent Earth’s shared natural history. Many indigenous communities have cultural and spiritual connections to fossil remains found on their ancestral lands, viewing commercial exploitation of these resources as a continuation of colonial extraction practices. Philosophical debates arise about whether unique natural history specimens should be treated differently from art or other collectibles, given their scientific importance and irreplaceability. The concept of “paleo-colonialism” has emerged to describe situations where fossils from developing nations end up primarily in wealthy Western institutions or private collections. Some ethicists propose that significant fossils should be considered part of the “common heritage of mankind,” similar to how international law treats objects found in Antarctica or the deep seabed. These complex ethical dimensions extend beyond simple questions of legality to fundamental issues of justice, cultural heritage, and scientific access.

High-Profile Auction Controversies

Auction houses have become central battlegrounds in the fossil debate, with several controversial sales igniting fierce criticism from the scientific community. In 2020, Christie’s auctioned “Stan,” a nearly complete T. rex skeleton, for a record-shattering $31.8 million to an undisclosed buyer, removing this scientifically valuable specimen from public access. The 2018 auction of a supposed “juvenile T. rex” generated outrage among paleontologists who disputed this identification and argued that such a rare specimen should not be sold privately regardless of its exact classification. In 1997, Sotheby’s sale of “Sue” the T. rex created similar controversy, though in that case, the Field Museum secured funding to purchase the specimen for public display and research. These high-profile sales demonstrate the enormous financial stakes involved and highlight how quickly important specimens can disappear from scientific access. The astronomical prices also incentivize more commercial collection, potentially encouraging illegal excavation or export in countries with restrictive laws but limited enforcement capabilities.

The Impact on Academic Research

The commercial fossil market has significantly impacted how paleontological research is conducted, creating both challenges and opportunities for scientists. When important specimens enter private collections, researchers may lose access to critical data points needed to understand evolutionary relationships or ancient ecosystems. Journal editors increasingly refuse to publish studies based on privately-held specimens that cannot be examined by other scientists, limiting what can be learned from commercially-traded fossils. Conversely, some academic institutions have developed relationships with commercial collectors who provide access to specimens they could not otherwise afford to excavate. Price inflation in the commercial market has strained museum acquisition budgets, making it increasingly difficult for public institutions to compete with wealthy private collectors. Some research projects now include specific strategies for engaging with commercial collectors, such as documenting specimens thoroughly before they disappear into private hands or developing loan agreements that allow scientific access while respecting private ownership.

The Role of Museums in the Debate

Museums occupy a complex middle ground in the fossil trade controversy, often walking a fine line between scientific principles and practical realities. Many major natural history museums have policies against purchasing commercially collected specimens to avoid encouraging the market, yet some have made exceptions for particularly significant fossils that might otherwise be lost to science. Museums frequently face difficult decisions when offered donations of commercially acquired specimens, weighing the scientific value against the ethical concerns of how they were obtained. Some institutions have developed hybrid approaches, partnering with commercial collectors on excavations while ensuring proper scientific protocols and public access to important finds. The financial pressures on museums have intensified as auction prices rise, forcing many to rely on wealthy donors to secure important specimens. These institutions often serve as the final arbiters determining which commercially collected fossils ultimately become available for research and public education, making their acquisition policies critically important to the broader debate.

Digital Technology and Fossil Access

Emerging technologies are creating new dimensions in the fossil ownership debate by potentially separating physical possession from scientific access. High-resolution 3D scanning and printing technologies now allow researchers to create detailed replicas or digital models of specimens, which can be shared widely even if the original fossil remains in private hands. Some museums and commercial collectors have collaborated on digitization projects that make detailed scans of privately owned fossils available to researchers worldwide. These technological solutions offer a potential middle path that could preserve scientific access while respecting private ownership rights. However, many paleontologists argue that digital copies, while valuable, cannot fully replace access to original specimens where microscopic details or chemical analyses might be necessary. The development of international databases of digitized specimens represents a promising approach to preserving scientific information even when physical specimens change hands. These technological developments are rapidly evolving and may significantly reshape how the scientific community interacts with the commercial fossil market.

The Economic Impact on Local Communities

The fossil trade has substantial economic implications for communities near significant fossil deposits, creating both opportunities and challenges. In regions like the American West, commercial fossil hunting provides livelihoods for local residents who might otherwise have limited economic options. These communities often develop specialized skills in fossil preparation and excavation that contribute to both commercial and scientific discoveries. Tourism centered around fossil sites brings additional revenue to rural areas, with some communities developing small museums or guided tours of local deposits. However, this economic activity can come with significant downsides if important scientific specimens are sold to distant collectors rather than remaining as local attractions. The distribution of benefits from fossil discoveries often raises questions of equity, particularly when high-value specimens found on private land generate profits primarily for landowners and dealers rather than broader community development. Some regions have developed cooperative models where commercial activities support local museums and educational programs, creating more sustainable economic benefits.

Potential Compromise Solutions

As the debate continues, various stakeholders have proposed compromise approaches that might balance commercial interests with scientific needs. Some advocate for a tiered system where scientifically significant specimens (such as new species or exceptionally preserved examples) would be required to enter public collections, while more common fossils could remain in the commercial market. Other proposals include mandatory waiting periods during which scientists can study newly discovered specimens before they enter private collections. Tax incentives for donating important fossils to public institutions might encourage private collectors to eventually transfer specimens to museums. Some commercial collectors have implemented voluntary best practices, including detailed documentation of discovery sites and collaboration with academic paleontologists. Public-private partnerships between museums and commercial collectors have shown promise in some regions, combining the efficiency of commercial operations with scientific oversight. These middle-ground approaches acknowledge the reality of the commercial market while attempting to preserve scientific access to the most important specimens.

The Future of Fossil Regulation

The regulatory landscape for fossil collection and sales continues to evolve, with several significant developments potentially reshaping the field. International agreements similar to those governing cultural artifacts could eventually be extended to cover significant paleontological specimens, creating more uniform standards across countries. Blockchain technology might be employed to track the provenance and ownership history of important fossils, making it more difficult to sell illegally obtained specimens. Several countries with rich fossil resources are currently developing new legislation that would more carefully balance scientific, commercial, and indigenous interests in fossil management. Transnational cooperation among law enforcement agencies has increased, making it more challenging to transport illegally exported specimens across borders. Scientific organizations are working to develop clearer guidelines for museums and journals regarding specimens of questionable provenance. These evolving regulatory frameworks reflect growing recognition that paleontological resources require specialized management approaches that differ from both typical natural resources and cultural artifacts.

Why This Debate Will Continue

The controversy surrounding dinosaur fossil sales shows no signs of resolution because it touches on fundamental tensions between competing values in modern society. The clash between market principles and scientific commons, between private property rights and collective heritage, and between short-term economic gain and long-term knowledge preservation creates a deeply complex problem resistant to simple solutions. The astronomical prices commanded by premier specimens continue to incentivize commercial collection despite scientific objections. Each new auction of a significant specimen reignites the debate, keeping the issue perpetually in public discourse. The international nature of the fossil trade means that even if some countries implement stronger regulations, the global market can adapt by focusing on regions with fewer restrictions. As new technological capabilities emerge for both finding and studying fossils, the practical and ethical questions surrounding their ownership will continue to evolve. This debate fundamentally concerns how we value and manage our understanding of Earth’s history, ensuring it will remain contentious as long as dinosaurs capture the public imagination and command high prices in the marketplace.

Conclusion

The tension between science and commerce in paleontology represents a microcosm of broader societal questions about how we balance private interests with public goods. While perfect solutions remain elusive, continued dialogue among scientists, commercial collectors, museums, indigenous communities, and policymakers offers the best path toward responsible stewardship of these irreplaceable windows into our planet’s past. As we navigate these complex issues, the goal should be ensuring that significant fossils remain available for scientific study and public education while respecting legitimate economic interests and cultural connections. The debate isn’t disappearing because what’s at stake is nothing less than how we understand, preserve, and share the remarkable story of life on Earth.