Imagine stepping into a world where dinosaurs rule the land, flowering plants are just beginning to bloom, and the air buzzes with insects that have been perfectly preserved for over 100 million years. These aren’t just fossils pressed into rock – they’re three-dimensional time capsules trapped in golden amber, offering us an unprecedented window into the daily lives of Cretaceous insects. From tiny gnats caught mid-flight to elaborate mating displays frozen in time, these amber specimens reveal secrets that would otherwise be lost forever.

The Amber Forest: Nature’s Perfect Time Machine

The Cretaceous period, spanning from 145 to 66 million years ago, was a golden age for both flowering plants and the insects that co-evolved with them. Ancient forests dominated by conifers and early flowering plants produced massive quantities of sticky resin that would eventually harden into amber. This resin didn’t just drip randomly – it flowed from tree wounds, creating natural traps that caught unsuspecting insects going about their daily routines.

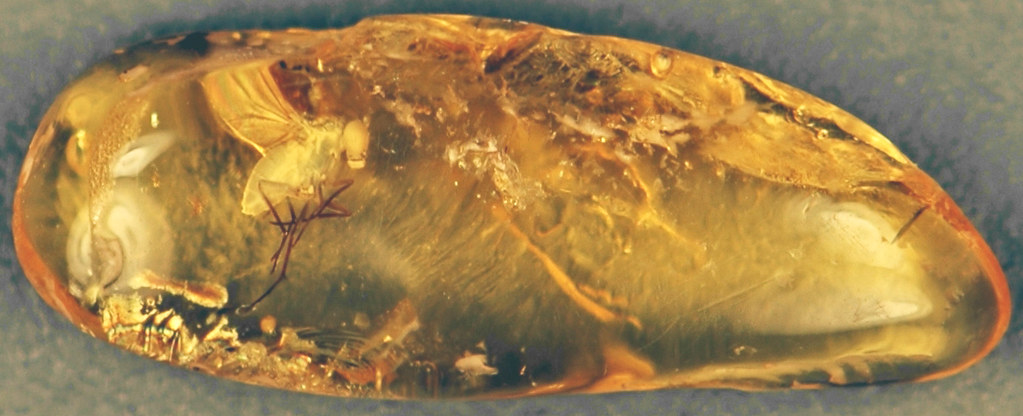

What makes these amber deposits so remarkable is their incredible preservation quality. Unlike other fossilization processes that compress organisms into flat imprints, amber preserves insects in three dimensions, maintaining their original colors, textures, and even microscopic details. Scientists have discovered amber forests from this period in locations ranging from Myanmar to Lebanon, each offering unique glimpses into ancient ecosystems.

Morning Rituals: Feeding Behaviors Frozen in Time

Dawn in the Cretaceous world brought a flurry of feeding activity, and amber has captured these moments with stunning clarity. Tiny flies with elongated proboscises are preserved while attempting to feed on plant nectar, their delicate mouthparts extended toward now-vanished flowers. These specimens reveal that many modern feeding behaviors were already well-established over 100 million years ago.

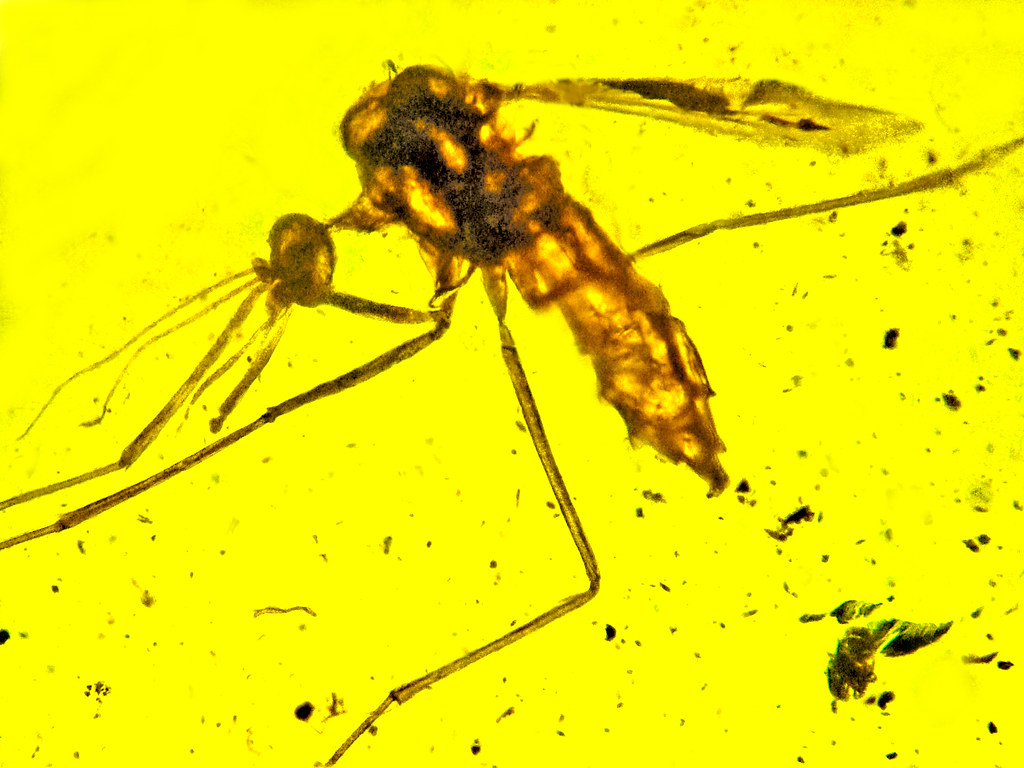

Perhaps most fascinating are the preserved blood-feeding insects, including early mosquitoes and biting flies. Some specimens contain visible blood meals in their abdomens, offering tantalizing possibilities for genetic analysis. While extracting dinosaur DNA remains firmly in the realm of science fiction, these blood-filled specimens do provide insights into the circulatory systems and blood chemistry of ancient animals.

The Great Pollinator Partnership

Amber specimens from the Cretaceous period document one of evolution’s most important partnerships – the relationship between flowering plants and their insect pollinators. Bees covered in ancient pollen grains are preserved mid-flight, their bodies loaded with the reproductive material of long-extinct plants. These discoveries show that sophisticated pollination strategies were already in place during the early days of flowering plant evolution.

Beetles, which are often overlooked as pollinators today, played crucial roles in Cretaceous ecosystems. Amber specimens reveal beetles with specialized structures for carrying pollen, including modified leg segments and body grooves designed to transport pollen efficiently. Some specimens even show beetles in the act of mating on flowers, combining reproduction with pollination duties.

Predator and Prey: Ancient Food Webs in Action

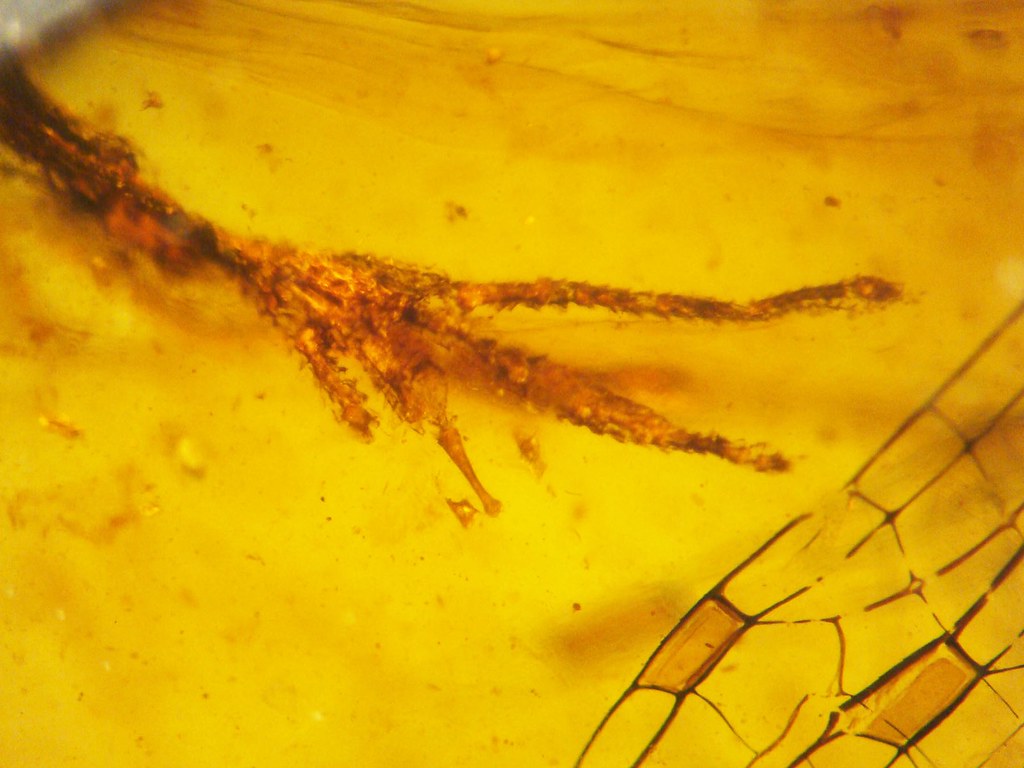

The Cretaceous amber record provides dramatic evidence of predator-prey relationships that played out millions of years ago. Spiders are preserved with their victims still wrapped in silk, while predatory beetles are caught in the act of attacking smaller insects. These frozen moments reveal feeding behaviors and hunting strategies that have remained remarkably consistent over geological time.

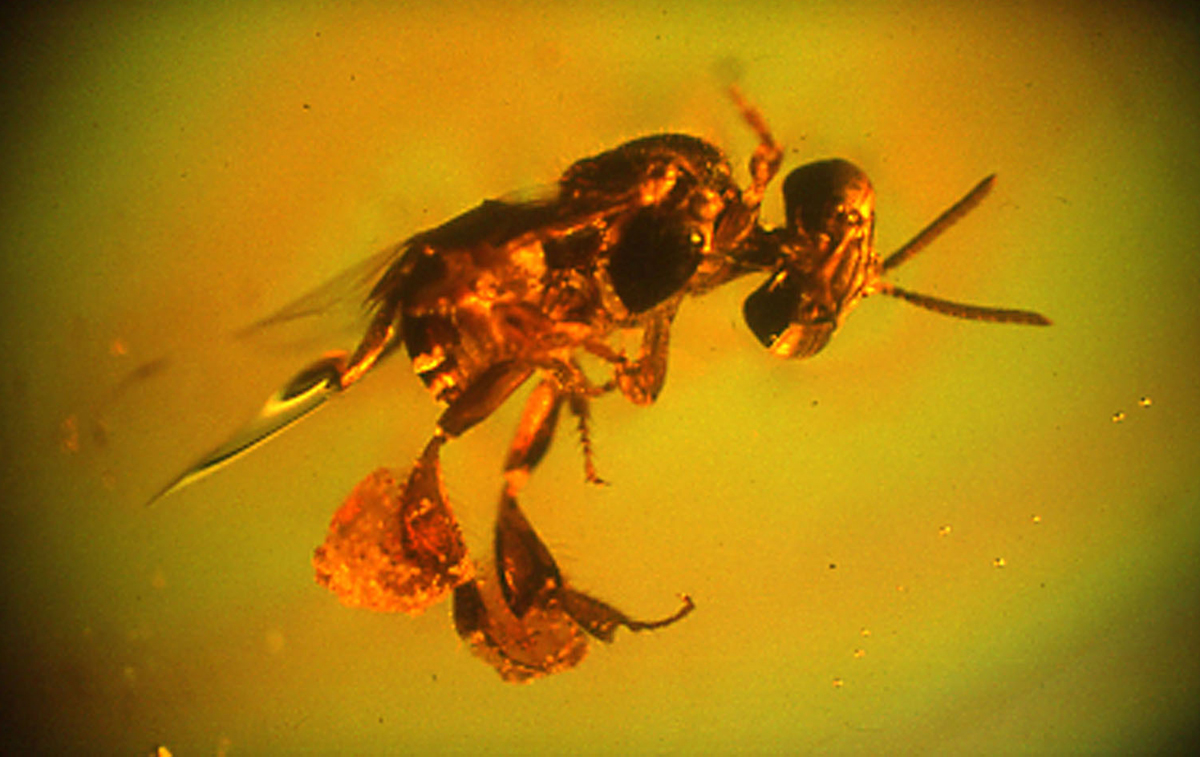

One of the most striking discoveries involves a spider that was caught while attacking a parasitic wasp. The wasp had just emerged from its host, a fly larva, creating a three-species interaction preserved in a single piece of amber. These complex ecological relationships demonstrate that Cretaceous ecosystems were just as intricate and interconnected as modern ones.

Social Insects: The Rise of Complex Societies

Amber deposits have yielded remarkable evidence of early social behavior in insects, including some of the oldest known ant colonies. Worker ants are preserved carrying food back to their nests, while soldier ants display enlarged heads and powerful jaws that make them formidable defenders. These specimens show that complex social structures were already evolving during the Cretaceous period.

Termite workers and soldiers are also well-represented in amber collections, often preserved alongside the wood fragments they were consuming. Some specimens capture termites in the process of building their elaborate tunnel systems, with workers carrying tiny balls of processed wood pulp. These discoveries suggest that the partnership between termites and their gut bacteria, which allows them to digest cellulose, was already established over 100 million years ago.

Mating Displays and Reproductive Strategies

Perhaps no aspect of ancient insect life is more dramatically preserved than mating behavior. Amber specimens capture flies, beetles, and other insects in the act of courtship and reproduction, providing intimate details about ancient sexual selection and reproductive strategies. Male flies with elaborate courtship displays are preserved alongside their intended mates, showing that sexual selection was a powerful evolutionary force even in the Cretaceous.

Some of the most remarkable specimens show insects engaged in complex mating rituals that lasted long enough to be captured in flowing resin. Dancing flies present nuptial gifts to potential mates, while others display enlarged eyes or modified appendages designed to attract partners. These preserved behaviors reveal that many modern courtship strategies have ancient origins.

Parasites and Disease: The Hidden Side of Ancient Life

Amber provides unique insights into the parasites and diseases that plague Cretaceous insects. Tiny parasitic wasps are preserved emerging from their hosts, while others are caught in the act of laying eggs in unsuspecting victims. These specimens reveal the complex web of parasitic relationships that existed millions of years ago.

Fungal infections are also well-documented in amber specimens, with some insects showing clear signs of being consumed by parasitic fungi. The fungi themselves are often preserved, creating a complete picture of ancient disease cycles. These discoveries suggest that the constant evolutionary arms race between hosts and parasites has been ongoing for hundreds of millions of years.

Camouflage and Defense: Survival Strategies in Amber

The preserved insects in amber showcase an incredible array of defensive strategies that helped them survive in dangerous Cretaceous environments. Stick insects with perfect leaf-like camouflage are frozen in poses that would have made them invisible to predators. Other insects display warning coloration, spines, or chemical defense glands that would have deterred attacks.

Some of the most impressive defensive adaptations are found in katydids and other orthopterans, which show elaborate modifications for both visual and acoustic camouflage. These insects developed wing patterns that perfectly mimicked leaves, complete with fake leaf veins and decay spots. The level of detail preserved in amber allows scientists to study these adaptations with unprecedented clarity.

Communication Networks: Ancient Signals in Stone

Amber specimens preserve evidence of sophisticated communication systems that allowed Cretaceous insects to coordinate their activities. Beetles with specialized sound-producing organs are preserved in positions that suggest they were calling to mates or warning of danger. The preservation quality is so high that scientists can study the microscopic structures used to generate these ancient sounds.

Chemical communication is also documented in amber, with some insects preserved alongside the pheromone-producing glands they used to send messages. Ant trails marked with chemical signals are occasionally preserved, showing how these social insects coordinated their foraging activities. These discoveries reveal that complex communication networks were already well-established in Cretaceous insect societies.

Ecosystem Engineers: Insects That Shaped Their World

The amber record shows that Cretaceous insects were not just passive participants in their ecosystems – they were active engineers who shaped their environment. Leaf-cutter ants are preserved carrying precisely cut leaf fragments, demonstrating the sophisticated agricultural systems they developed to cultivate fungal gardens. These early farming activities had profound effects on plant evolution and ecosystem dynamics.

Wood-boring beetles and their larvae are preserved within the tunnels they carved through ancient trees, showing how these insects played crucial roles in forest nutrient cycling. Some specimens reveal the complex gallery systems that beetle families constructed, with nursery chambers and waste disposal areas that rival modern architectural planning. These engineering feats show that insects were already major forces in shaping terrestrial ecosystems.

Evolutionary Experiments: Failed Lineages and Lost Innovations

One of the most fascinating aspects of the amber record is what it reveals about evolutionary experiments that didn’t survive to the present day. Bizarre insects with unique combinations of features are preserved in amber, representing evolutionary lineages that explored different solutions to survival challenges. Some insects developed multiple sets of wings, while others experimented with unusual feeding strategies or body plans.

These extinct lineages provide crucial insights into the evolutionary pressures that shaped modern insect diversity. By studying what didn’t work, scientists can better understand why certain traits were successful while others were evolutionary dead ends. The amber record serves as a vast library of natural experiments, documenting both the successes and failures of insect evolution.

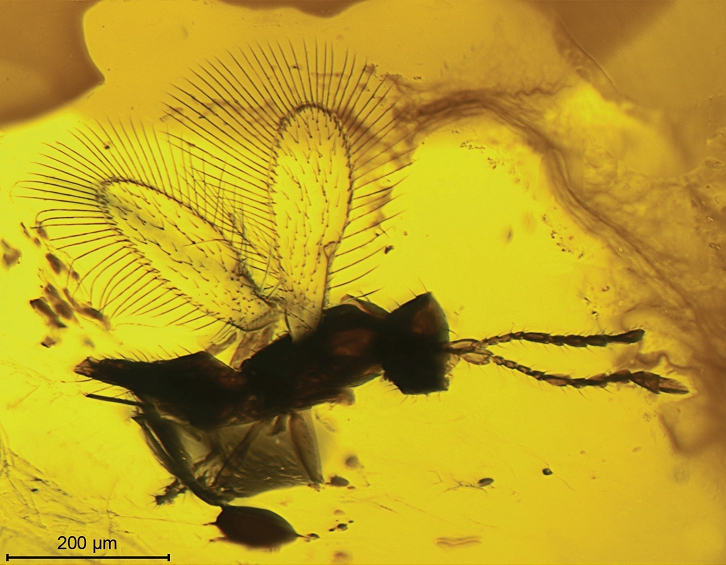

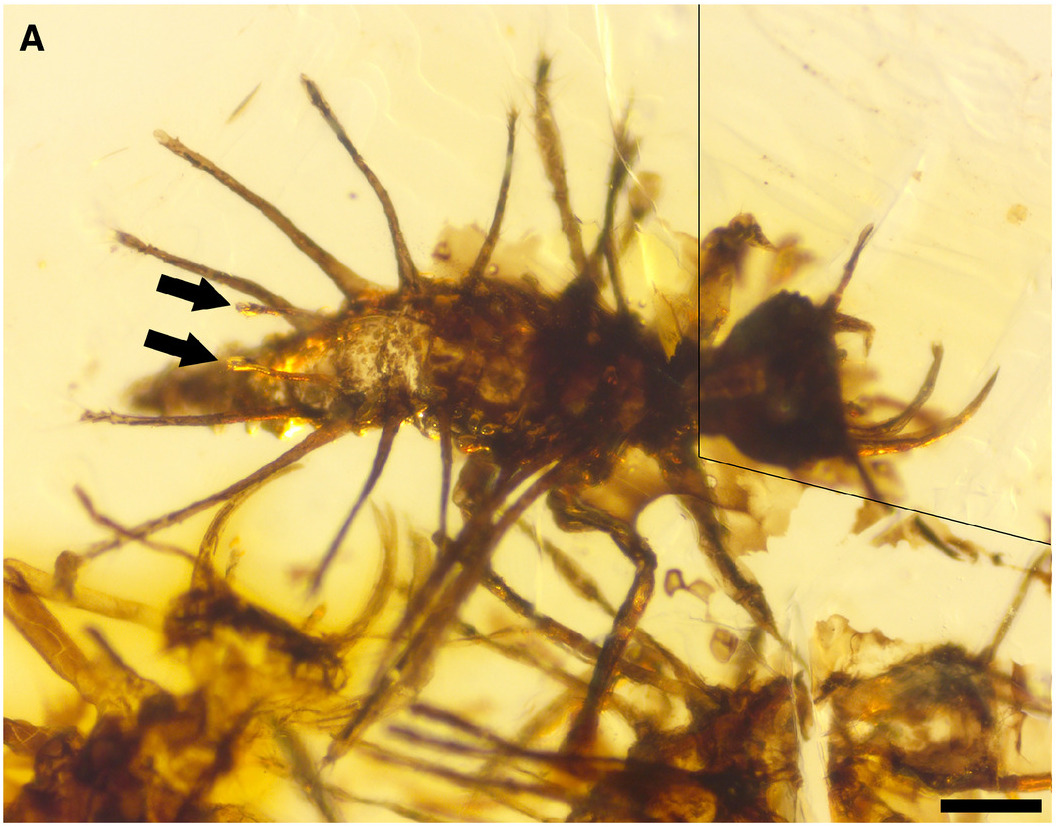

Microscopic Worlds: The Smallest Inhabitants

While larger insects often capture the most attention, amber also preserves incredibly detailed views of microscopic arthropods that inhabited Cretaceous ecosystems. Tiny springtails, mites, and other micro-arthropods are preserved with such clarity that individual sensory organs and microscopic structures are visible. These small creatures played enormous roles in nutrient cycling and ecosystem function.

Some amber specimens contain entire microscopic ecosystems, with bacteria, fungi, and single-celled organisms preserved alongside the insects. These microbial communities provide insights into ancient ecological relationships and the evolution of symbiotic partnerships. The preservation of these microscopic worlds offers a level of detail that is impossible to achieve with other types of fossils.

Seasonal Cycles: Evidence of Ancient Rhythms

The amber record provides evidence that Cretaceous insects followed seasonal patterns similar to those seen in modern ecosystems. Clusters of insects preserved together suggest mass emergence events, while the presence of dormant stages indicates that some species underwent seasonal dormancy. These patterns reveal that ancient ecosystems were subject to the same climatic rhythms that drive modern seasonal cycles.

Migration patterns are also preserved in amber, with some specimens showing insects loaded with fat reserves or displaying other physiological adaptations for long-distance travel. These discoveries suggest that seasonal migration was already an important survival strategy for some Cretaceous insects. The amber record captures these ancient rhythms in remarkable detail, providing insights into how climate influenced insect behavior millions of years ago.

The Living Museum: What Amber Teaches Us Today

The incredible preservation quality of Cretaceous amber has revolutionized our understanding of ancient life, providing details that would be impossible to obtain from conventional fossils. These specimens serve as a direct link to ecosystems that existed over 100 million years ago, offering insights into evolutionary processes, ecological relationships, and the origins of modern biodiversity.

Modern research techniques continue to reveal new information from these ancient specimens. Advanced imaging technologies allow scientists to study internal structures without damaging the amber, while chemical analysis can identify ancient proteins and other biomolecules. Each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of how life on Earth evolved and adapted to changing conditions.

The amber record also provides valuable perspectives on current environmental challenges. By studying how ancient ecosystems responded to climate change and other pressures, scientists can better understand the resilience and vulnerability of modern insect communities. These ancient time capsules remind us that life has always been subject to change, but they also demonstrate the incredible adaptability and creativity of evolution in finding solutions to survival challenges.

What secrets do you think these golden time capsules might still be hiding?