For centuries, paleontologists have unearthed the remains of dinosaurs, piecing together their physical characteristics and behaviors from bones, tracks, and other preserved evidence. Among these fascinating discoveries, fossilized dinosaur eggs stand out as particularly significant finds, potentially offering rare glimpses into the reproductive behaviors and parenting strategies of these ancient creatures. As scientists continue to study these delicate remnants of prehistoric life, an intriguing question emerges: Do fossilized eggs provide concrete evidence of complex parental behaviors among dinosaurs? This article explores the current scientific understanding of dinosaur eggs, nesting behaviors, and what they might reveal about dinosaur parenting strategies.

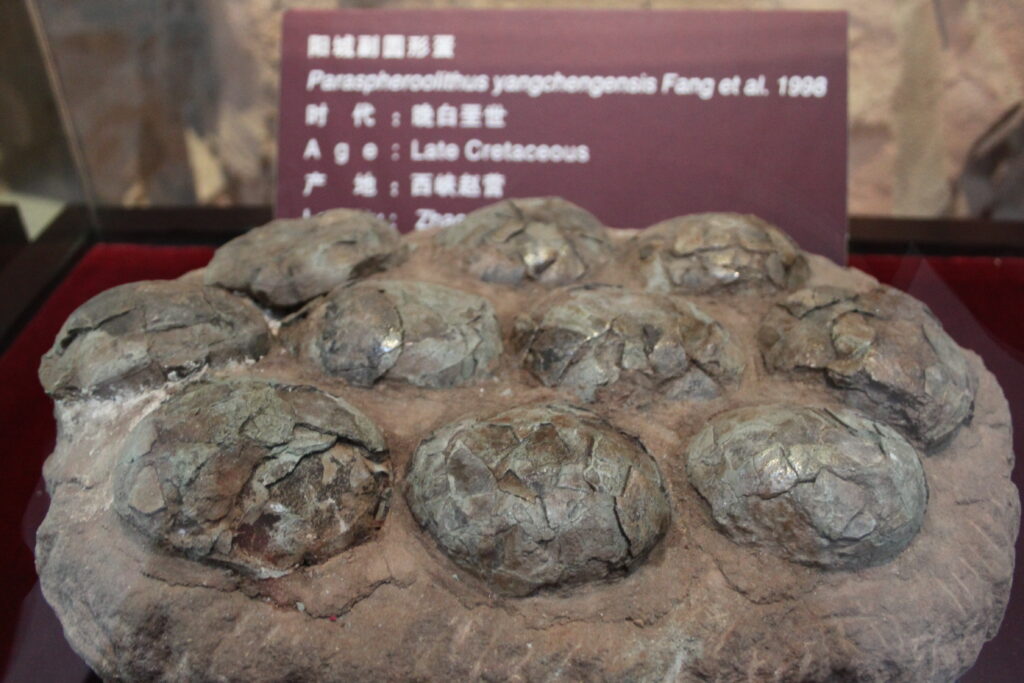

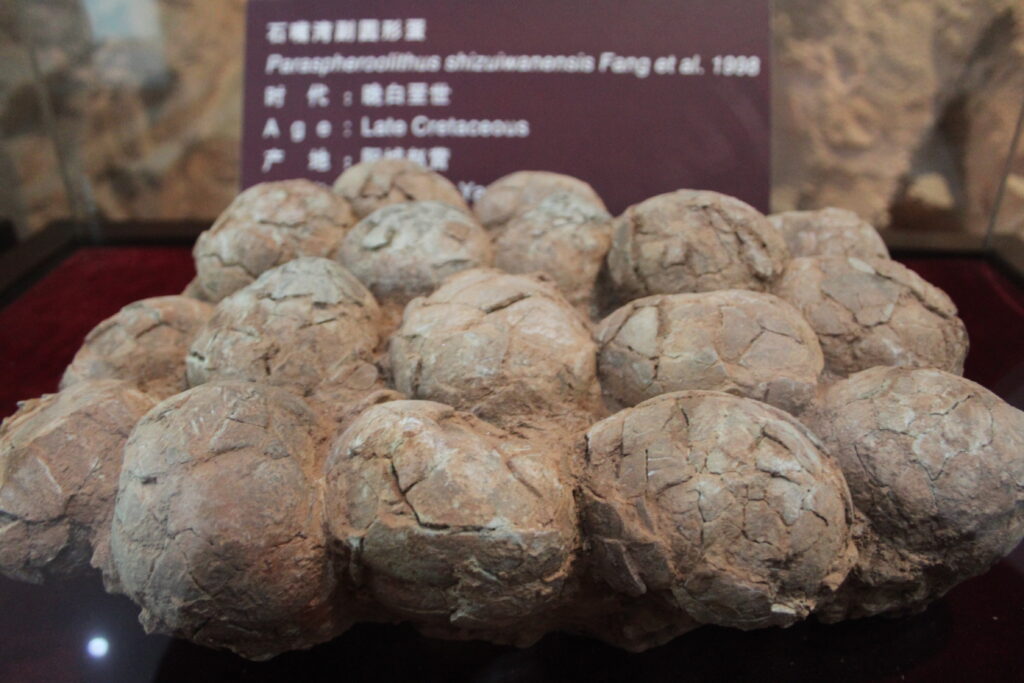

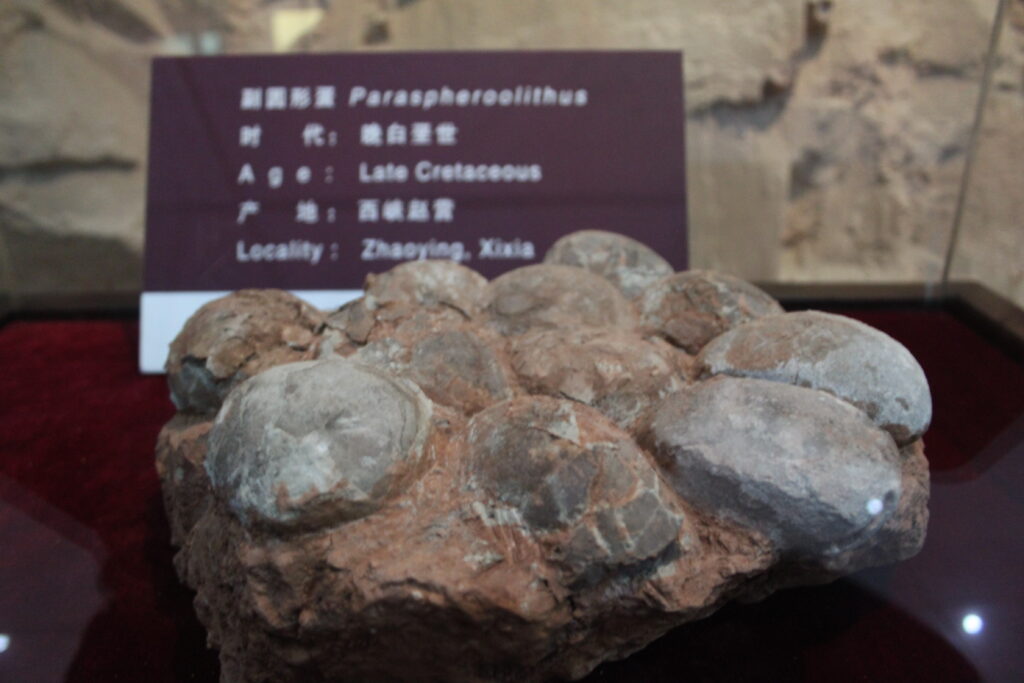

The Remarkable Preservation of Dinosaur Eggs

Dinosaur eggs represent some of the most extraordinary fossils in the paleontological record, preserving not just the hard shell but occasionally embryonic remains and nest structures. These fossilized eggs typically range from the size of a chicken egg to as large as a football, depending on the species. The fossilization process occurs when minerals replace the original organic materials over millions of years, preserving the structure and sometimes even microscopic details of the eggshell. For paleontologists, well-preserved egg fossils provide a unique window into dinosaur reproduction that skeletal remains alone cannot offer. The first scientifically documented dinosaur eggs were discovered in France in the 1860s, but it wasn’t until 1923, when explorers from the American Museum of Natural History found nests in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, that scientists began to seriously study what eggs could tell us about dinosaur behavior.

Nest Arrangements and Their Significance

The arrangement of eggs within fossilized nests offers compelling clues about dinosaur reproductive behavior. Paleontologists have discovered various nest configurations, from the circular arrangements of eggs by sauropods to the paired arrangements in some theropod nests. These patterns suggest intentional placement rather than random egg-laying, indicating at least some level of parental care or nest preparation. In the Gobi Desert, scientists found Oviraptor nests with eggs arranged in concentric circles, suggesting the parent dinosaur may have sat atop the nest with eggs arranged carefully around its body. Similarly, Maiasaura (meaning “good mother lizard”) nests discovered in Montana revealed eggs arranged in spiral patterns within shallow depressions, with evidence suggesting the parents may have returned periodically to these colonial nesting grounds. These organized nest structures indicate that dinosaurs were not simply laying eggs randomly but engaged in specific nesting behaviors.

Embryonic Development and Hatching Evidence

Advanced imaging techniques have revolutionized scientists’ ability to study dinosaur embryos within their eggs, providing unprecedented insights into development and potential parenting needs. CT scans and other non-destructive methods reveal embryonic bones, teeth, and sometimes even soft tissue impressions. These studies show that many dinosaur species had extended incubation periods, with some estimated to last six months or longer, significantly longer than modern reptiles but shorter than the largest birds. The extended development time suggests a potential vulnerability period during which parental protection might have been advantageous. Additionally, some fossilized nests contain eggshell fragments scattered in patterns consistent with hatching rather than predation, indicating successful births. In certain hadrosaur and some theropod nests, the presence of nestling remains with evidence of growth after hatching suggests that juveniles remained in or near the nest, possibly receiving parental care.

Brooding Behaviors Preserved in Stone

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for dinosaur parenting comes from spectacular fossils showing adult dinosaurs brooding their eggs. The most famous example is a fossil discovered in Mongolia in 1993 showing an Oviraptor positioned directly over a nest of eggs, with its limbs arranged in a brooding position similar to modern birds. Initially, this dinosaur was thought to be raiding the nest (hence the name “egg thief”), but further analysis revealed these were its eggs. The skeleton’s positioning, with arms spread over the egg, strongly suggests brooding behavior to provide warmth and protection. Similar specimens of other small theropods have been found in China’s Liaoning Province, where the volcanic ash that killed these dinosaurs simultaneously preserved them in brooding positions. These fossils provide strong evidence that at least some dinosaur species engaged in direct parental care comparable to that seen in modern birds, their living descendants.

Colony Nesting and Social Parenting

Numerous dinosaur species appear to have nested in colonies, suggesting potential social dimensions to their parenting behaviors. Extensive nesting grounds have been discovered around the world, from Argentina to Mongolia, where hundreds of nests are clustered together in what were dinosaur rookeries. These colonial nesting sites, particularly common among hadrosaurs and sauropods, suggest advantages similar to those observed in modern birds that nest in colonies: protection from predators through safety in numbers and possibly cooperative parenting. At sites like Egg Mountain in Montana, Maiasaura nests are spaced approximately one adult body length apart, suggesting the dinosaurs nested close enough for social interaction while maintaining individual territories. The consistent spacing between nests at these sites indicates organized community behavior rather than random nest placement, pointing to complex social structures surrounding reproduction and potentially shared parenting responsibilities among colony members.

Growth Rates and Parental Investment

Analysis of dinosaur growth patterns through bone histology provides indirect evidence of potential parental care. Studies of bone microstructure in juvenile dinosaurs reveal that many species grew extraordinarily rapidly during early life, at rates more similar to mammals and birds than modern reptiles. Such accelerated growth would have required substantial nutrition, suggesting either particularly nutrient-rich environments or, more likely, parental provisioning of food. Maiasaura nestlings, for example, show worn teeth that indicate they were eating processed plant material rather than foraging independently. This suggests parents may have brought food to the nest. Similarly, the growth rates of young tyrannosaurs and other predatory dinosaurs would have required significant protein intake that would be difficult for helpless juveniles to obtain without parental assistance. These growth patterns suggest a level of parental investment beyond simple egg-guarding, potentially including active feeding of offspring.

Contrasting Strategies: The Diversity of Dinosaur Parenting

The fossil record suggests dinosaurs exhibited a spectrum of parenting strategies rather than a uniform approach across all species. While some theropods like Oviraptor show evidence of active brooding, large sauropods likely employed strategies more similar to sea turtles—laying many eggs and providing minimal post-hatching care. This diversity makes evolutionary sense given the vast range of dinosaur body sizes and ecological niches. The 40-ton Argentinosaurus, for instance, would have been physically incapable of brooding eggs without crushing them, and likely laid eggs in carefully selected locations before departing. In contrast, smaller dinosaurs like Troodon, with its relatively large brain, appear to have engaged in more complex parenting behaviors. Modern crocodilians and birds—the living relatives of dinosaurs—exhibit similarly diverse strategies, from the intensive parenting of hornbills to the minimal investment of megapode birds that bury eggs in mounds. This diversity suggests dinosaurs likely evolved varied parenting strategies adapted to their specific ecological constraints and opportunities.

Evidence from Trackways and Footprints

Fossilized trackways occasionally provide supporting evidence for parental behavior by showing adults and juveniles traveling together. Several sites worldwide preserve a series of footprints where large dinosaur tracks are accompanied by smaller tracks of the same species, suggesting family groups moving together. A notable example comes from the Early Cretaceous of South Korea, where sauropod trackways show evidence of adults potentially surrounding juveniles as they moved—a protective behavior seen in modern elephants. Similarly, trackways in Colorado show multiple generations of hadrosaurs traveling together, suggesting family groups that stayed together after hatching. These trace fossils, while not directly connected to nests, complement the egg evidence by suggesting extended parental care beyond the nesting period. The orientation and spacing of these multi-sized trackways often indicate coordinated movement rather than random association, further supporting the hypothesis that some dinosaur species engaged in extended family behaviors.

The Bird-Dinosaur Connection: Evolutionary Implications

The parenting behaviors observed in modern birds offer important context for interpreting dinosaur parenting, particularly given the evolutionary connection between the two groups. Birds are living dinosaurs—the surviving descendants of maniraptoran theropods. Modern birds display the most complex and varied parenting strategies among living reptiles, ranging from precocial species whose chicks are relatively independent to altricial species with extended parental care. This diversity likely has deep evolutionary roots in their dinosaur ancestors. The discovery of brooding behavior in theropods phylogenetically close to birds strengthens this connection, suggesting that bird-like parenting may have evolved gradually rather than appearing suddenly after birds diverged from other dinosaurs. Feathered dinosaurs like Microraptor and Sinosauropteryx share numerous anatomical features with early birds, and likely shared behavioral traits as well. The evidence increasingly suggests that many behaviors once thought unique to birds, including complex parenting, originated in their dinosaur ancestors.

Challenges in Interpreting the Evidence

Despite the growing body of evidence, paleontologists face significant challenges when interpreting parental behaviors from fossils. Taphonomic processes—the physical, chemical, and biological factors affecting preservation—can create misleading impressions. For example, an adult dinosaur found near eggs might have been a predator rather than a parent, or might have been buried near the nest by coincidence. Environmental factors like floods or volcanic eruptions that preserve fossils can also create artificial associations. Additionally, behaviors leave fewer traces than physical structures, making parenting strategies particularly difficult to reconstruct definitively. Scientists must also avoid anthropomorphizing dinosaurs by projecting human or modern bird behaviors onto them without sufficient evidence. To address these challenges, researchers increasingly rely on multiple lines of evidence—combining egg microstructure, nest arrangement, growth rates, and comparative studies with living relatives—to build more robust interpretations of dinosaur parenting behaviors.

Recent Discoveries Expanding Our Understanding

Recent discoveries continue to refine our understanding of dinosaur parenting behaviors. In 2017, researchers described an extraordinary fossil from China: a baby Beibeilong inside an egg within a nest, belonging to a group of bird-like oviraptorosaurs. This 90-million-year-old “Baby Louie” specimen provided new insights into embryonic development and nest structures. Another groundbreaking discovery came from Argentina in 2020, where scientists found the first evidence of communal nesting in titanosaur sauropods, with multiple females laying eggs in the same nest structure. In Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, ongoing excavations continue to uncover nesting grounds with eggs containing embryonic material that allows for a better understanding of development. Advanced techniques like synchrotron radiation and spectroscopic analysis now allow scientists to detect original proteins and pigments in some exceptionally preserved eggs, offering chemical evidence of nesting environments. These continuing discoveries consistently support the view that many dinosaur species invested significantly in reproduction beyond simply laying eggs, demonstrating parenting behaviors ranging from nest construction to possible food provisioning.

Implications for Dinosaur Social Complexity

The evidence for parental care in dinosaurs has broader implications for understanding their social complexity and cognitive capabilities. Extended parenting behaviors require substantial behavioral flexibility and social coordination, suggesting dinosaurs possessed more sophisticated cognitive abilities than traditionally assumed. Colonial nesting, in particular, requires complex social navigation skills to maintain territories while cooperating for mutual defense. The apparent teaching behaviors implied by some evidence, where juveniles seem to have learned specific skills before leaving the nest, suggest information transfer between generations. These social behaviors align with anatomical evidence showing some dinosaur groups, particularly maniraptoran theropods and certain ornithischians, had relatively large brains for their body size. The combination of anatomical and behavioral evidence is causing paleontologists to reevaluate traditional views of dinosaurs as simplistic creatures, instead recognizing them as animals with complex social lives comparable in some ways to modern birds and mammals. This revised understanding highlights that sophisticated parenting and social behaviors evolved in dinosaurs long before mammals dominated terrestrial ecosystems.

Conclusions: What Fossilized Eggs Tell Us

Fossilized eggs provide compelling but incomplete evidence of complex parenting behaviors among dinosaurs. The accumulated research strongly indicates that dinosaur reproductive strategies were diverse, with some species, particularly smaller theropods, demonstrating parental behaviors remarkably similar to modern birds, while others likely provided minimal post-laying care. The organization of nests, evidence of brooding, growth rates of juveniles, and occasional preservation of family groups all point toward various levels of parental investment across different dinosaur lineages. However, the fragmentary nature of the fossil record means we may never know the full range and nuance of dinosaur parenting behaviors. What remains clear is that the traditional view of dinosaurs as cold, uninvolved parents has been thoroughly dismantled by modern paleontology. As new analytical techniques and discoveries continue to emerge, our understanding of dinosaur parenting will undoubtedly become more nuanced, further illuminating the complex behaviors of these remarkable animals that dominated Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years.