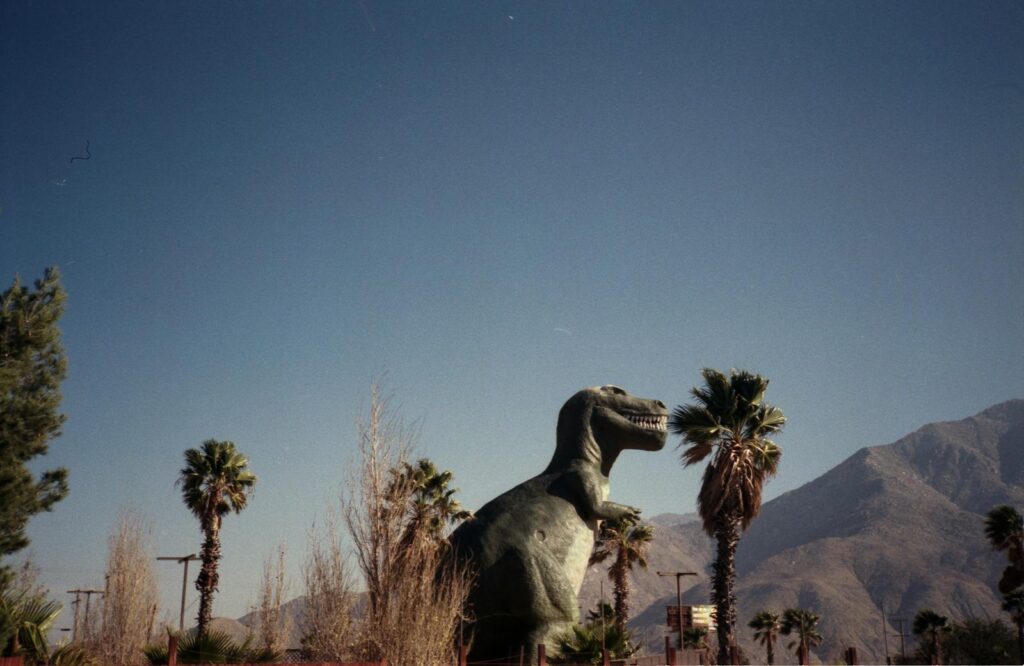

In the annals of paleontology, few figures stand as tall as Barnum Brown, the legendary fossil hunter whose discoveries revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric life. Sporting his signature cowboy hat across remote badlands and treacherous cliffs, Brown unearthed some of the most important dinosaur specimens ever found, including the first Tyrannosaurus rex. His remarkable career spanning seven decades transformed paleontology from a scientific curiosity into a discipline that captured the public imagination.

This is the story of an extraordinary man whose passion for fossils took him from humble beginnings to becoming one of the most celebrated scientists of his era—a tale of adventure, perseverance, and world-changing discoveries made by the man they called “Mr. Bones.”

Early Life and Education

Born on February 12, 1873, in Carbondale, Kansas, Barnum Brown was named after the famous showman P.T. Barnum, foreshadowing the sense of spectacle that would define his later career. Growing up on the family farm, young Brown developed an early fascination with natural history, collecting fossils and rocks from local creek beds and outcroppings. His formal education began at the University of Kansas, where he studied geology under the renowned paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston, who recognized Brown’s exceptional talent for fossil hunting.

After graduating, Brown continued his education at Columbia University, where he further honed his geological expertise while working part-time for the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. This connection would prove pivotal, as the museum would become his professional home for most of his extraordinary career, sponsoring many of his most significant expeditions.

The Making of a Fossil Hunter

Brown’s transformation from academic to legendary field paleontologist began in earnest with his first major expedition to the fossil-rich Jurassic beds of Wyoming in 1896. Working under the direction of AMNH curator Henry Fairfield Osborn, Brown demonstrated an almost uncanny ability to locate fossils where others saw nothing but barren rock. Colleagues marveled at what they called his “fossil sense”—an intuitive understanding of where ancient remains might be preserved. This natural talent, combined with his remarkable physical endurance and willingness to work in harsh conditions, quickly established Brown as an invaluable asset to the museum.

By the turn of the century, he had developed innovative techniques for excavating and preserving fossils, including the plaster jacket method still used by paleontologists today. His meticulous approach to collecting would ultimately revolutionize how fieldwork was conducted, setting standards that transformed paleontological practices worldwide.

The Historic Discovery of Tyrannosaurus Rex

Brown’s most celebrated achievement came in 1902 during an expedition to the Hell Creek Formation in Montana. While exploring the rugged badlands, he uncovered massive fossilized bones unlike anything previously documented in the scientific record. These remains would eventually be identified as belonging to Tyrannosaurus rex, the most fearsome predator of the Late Cretaceous period. Henry Fairfield Osborn formally described and named the species in 1905, with Brown’s specimen serving as the holotype—the definitive example against which all future T. rex discoveries would be compared.

The significance of this find cannot be overstated; it introduced the world to what would become the most iconic dinosaur in history. Brown himself would go on to discover several more T. rex specimens throughout his career, including a nearly complete skeleton in 1908 that remains one of the finest examples ever found and continues to be a centerpiece attraction at the American Museum of Natural History.

The Distinctive Cowboy Image

Brown cultivated a distinctive persona that set him apart from the typical academic scientists of his era. His trademark wide-brimmed cowboy hat, tailored suits, and polished boots created an image that was part Wild West explorer and part sophisticated New York intellectual. This carefully crafted appearance served multiple purposes, both practical and strategic. In the field, his western attire was functional, protecting him from the harsh elements of the remote regions where he worked.

However, Brown was also keenly aware of the power of public relations, and his distinctive look made him instantly recognizable in photographs and news reports. As dinosaurs captured the public imagination, Brown became paleontology’s first true celebrity scientist, using his charismatic presence to generate public interest and, crucially, financial support for further expeditions. His cowboy image helped transform paleontology from an obscure scientific discipline into something exciting and accessible to everyday Americans.

Expeditionary Adventures Around the Globe

While Brown’s name is forever linked to the American West, his fossil-hunting expeditions took him to six continents over the course of his remarkable career. In the 1910s, he led groundbreaking excavations in Alberta, Canada, where he discovered numerous dinosaur specimens, including the first documented remains of Albertosaurus. His international work began in earnest after World War I, with extensive fieldwork throughout South America, particularly in Patagonia, where he collected important mammalian fossils.

Between 1921 and 1923, Brown participated in the famous Central Asiatic Expeditions to Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, working alongside Roy Chapman Andrews in what became one of the most celebrated paleontological projects in history. Later expeditions took him to India, Burma, and Africa, making Brown one of the most widely traveled scientists of his generation. His global approach to paleontology helped establish connections between fossil records of different regions, contributing significantly to early understanding of prehistoric animal distributions and continental drift theory.

Innovative Field Techniques

Brown revolutionized paleontological fieldwork through his innovative approaches to fossil extraction and preservation. Faced with the challenge of removing massive dinosaur remains from remote locations, he developed transportation methods that sometimes bordered on the ingenious. In one famous instance, lacking sufficient pack animals, Brown dynamited a large dinosaur skeleton into manageable pieces, carefully recording their positions for later reassembly at the museum. He pioneered the use of plaster jackets reinforced with burlap to protect fragile fossils during transport, a technique that remains standard practice in the field today.

Brown was also among the first paleontologists to recognize the importance of documenting the precise geological context of fossil discoveries, maintaining detailed field notes and photographs that provided crucial scientific data beyond the specimens themselves. His methodical approach set new standards for professional field paleontology, transforming it from treasure hunting into a rigorous scientific discipline with established protocols and best practices.

Beyond Dinosaurs: Brown’s Diverse Discoveries

Though best known for his dinosaur discoveries, Brown’s scientific contributions extended far beyond the reptilian giants of the Mesozoic era. Throughout his career, he collected thousands of specimens representing the entire spectrum of prehistoric life, from ancient marine invertebrates to Ice Age mammals. His excavations at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles yielded crucial specimens of Pleistocene fauna, including saber-toothed cats, giant sloths, and mastodons. In Cuba, Brown conducted pioneering work on extinct mammals unique to the Caribbean islands, uncovering evidence of previously unknown species.

He also made significant contributions to the study of early hominids, participating in important excavations of ancient human remains in Asia. This breadth of scientific interest reflected Brown’s comprehensive approach to paleontology, recognizing that understanding Earth’s past required investigating the full diversity of life forms throughout geological time. His wide-ranging collections dramatically expanded the scientific resources available to researchers at the American Museum of Natural History and other institutions worldwide.

Secret Work as a World War II Intelligence Agent

One of the most intriguing chapters in Brown’s life remained largely unknown until decades after his death—his covert work for American intelligence during World War II. Under the guise of conducting geological surveys for oil companies, Brown provided the U.S. government with strategic information about potential petroleum resources in various countries.

This fieldwork, conducted primarily in the Middle East, North Africa, and South America, allowed him to gather intelligence about regions of strategic importance while maintaining his scientific cover. Though the full extent of his espionage activities remains classified, declassified documents have revealed that Brown’s geological expertise and international connections made him an invaluable asset to American wartime intelligence efforts.

His ability to travel in sensitive regions without arousing suspicion, combined with his scientific training in observing and documenting landscapes, made him ideally suited for this clandestine role. This remarkable chapter adds another dimension to Brown’s already extraordinary career, revealing him as not only a pioneering scientist but also a patriot who leveraged his unique skills in service to his country.

Relationship with the American Museum of Natural History

Brown’s relationship with the American Museum of Natural History spanned nearly 70 years, making him one of the institution’s most important figures. Initially hired in 1897 as an assistant in vertebrate paleontology, he quickly became indispensable to the museum’s growing dinosaur program. Under the patronage of AMNH president Henry Fairfield Osborn, Brown received unprecedented support for ambitious collecting expeditions that would dramatically expand the museum’s holdings. By the 1930s, largely through Brown’s efforts, the AMNH possessed the world’s premier collection of dinosaur fossils, drawing visitors and researchers from around the globe.

Beyond his fieldwork, Brown played a crucial role in designing the museum’s famous dinosaur halls, working closely with artists and preparators to create scientifically accurate mounted skeletons and displays. His public lectures at the museum attracted enormous crowds, helping to popularize paleontology among ordinary Americans. Though Brown occasionally had professional disagreements with museum administrators over expedition funding and research priorities, his lifetime association with the institution defined both his career and the museum’s international reputation in paleontology.

Public Persona and Media Impact

Brown may have been the first true celebrity scientist in American paleontology, cultivating a public image that captured the imagination of both the scientific community and the general public. Newspaper accounts of his expeditions often portrayed him as a daring adventurer, braving harsh wilderness conditions in pursuit of prehistoric monsters.

Brown skillfully leveraged this media attention, giving interviews and writing popular articles that brought the excitement of paleontological discovery to millions of readers. His regular appearances in newsreels and public lectures made him one of the most recognizable scientific figures of his era. Unlike many of his academic contemporaries who avoided publicity, Brown understood that public engagement was crucial for generating the financial and institutional support needed for his ambitious research program.

His approach to science communication represented a significant departure from the typically insular academic tradition, pioneering a model of the scientist as public figure that would influence later generations of researchers. Brown’s media savvy helped transform dinosaurs from obscure scientific curiosities into cultural icons that continue to fascinate the public today.

Legacy and Impact on Paleontology

Barnum Brown’s legacy extends far beyond his individual discoveries, significant though they were. His systematic approach to fossil collection transformed paleontology from a loosely organized pursuit into a methodical scientific discipline with standardized field practices. The vast collections he assembled continue to serve as primary research materials for contemporary scientists, with new analyses of specimens he collected still yielding important scientific insights nearly a century later.

Brown also played a crucial role in training the next generation of paleontologists, mentoring numerous students who would go on to distinguished careers of their own. His emphasis on the importance of precise geological context and comprehensive collecting helped establish modern standards for paleontological research. Perhaps most significantly, Brown’s work permanently altered public perception of dinosaurs and prehistoric life, moving them from scientific obscurity into mainstream culture.

The dramatic mounted skeletons he helped create for the American Museum of Natural History established the visual template for how generations of people would imagine dinosaurs, influencing scientific illustrations, fiction, film, and other media representations that continue to shape our collective understanding of Earth’s prehistoric past.

Personal Life and Character

Behind the public persona of the intrepid fossil hunter was a complex individual whose personal life often reflected the same intensity that characterized his professional pursuits. Brown was married twice, first to Marion Raymond in 1903, a union that produced his only child, Frances. Following their divorce, he married Lilian McLaughlin in 1922, who often accompanied him on expeditions and became an accomplished field photographer in her own right.

Colleagues described Brown as charismatic and driven, with boundless energy that allowed him to work punishing hours in difficult field conditions well into his seventies. He was known for his meticulous attention to detail, keeping extensive journals and correspondence that documented both his scientific observations and his personal reflections.

Despite his celebrity status, those who knew him well noted that Brown remained genuinely passionate about the scientific significance of his work rather than personal fame. He maintained a wide circle of friends both within and outside scientific circles, counting among his acquaintances prominent figures in business, politics, and the arts. This broad network of connections served him well throughout his career, helping him secure funding and access to promising fossil localities around the world.

Final Years and Enduring Recognition

Even in his later years, Brown maintained an active field schedule that would have exhausted researchers half his age. Though he officially retired from the American Museum of Natural History in 1942 at age 69, he continued to work as a research associate, consulting on exhibitions and occasionally participating in expeditions. In his final decade, Brown served as a consultant to various petroleum companies, applying his geological expertise to the search for energy resources—a role that both supplemented his modest pension and kept him engaged in scientific fieldwork. His last major paleontological project came in the early 1950s when, in his late seventies, he supervised excavations at sites in the western United States.

Brown passed away on February 5, 1963, just a week shy of his 90th birthday, leaving behind an unparalleled scientific legacy. In recognition of his extraordinary contributions, numerous dinosaur species have been named in his honor, including Anchiceratops brownii and Leptoceratops brownii. Perhaps the most fitting tribute came in 1998 when a newly identified tyrannosaur species was named Dryptosaurus brownii, forever linking him with the magnificent predators that had defined his remarkable career.

Conclusion

Barnum Brown’s life story reads like an adventure novel—a Kansas farm boy who became the world’s most famous dinosaur hunter, uncovered prehistoric monsters, served as a secret agent, and transformed our understanding of Earth’s distant past. His cowboy-hatted figure standing proudly beside enormous fossil discoveries has become an iconic image in the history of science. Through dedication, innovation, and sheer persistence, Brown built a legacy that continues to influence paleontology and public understanding of prehistoric life.

His greatest discovery, Tyrannosaurus rex, remains the most recognizable dinosaur in the world, serving as an enduring ambassador for the science he helped pioneer. As new generations of paleontologists follow in his footsteps, they build upon the foundations laid by the remarkable man who showed us that beneath the earth’s surface lay the keys to understanding our planet’s extraordinary past.