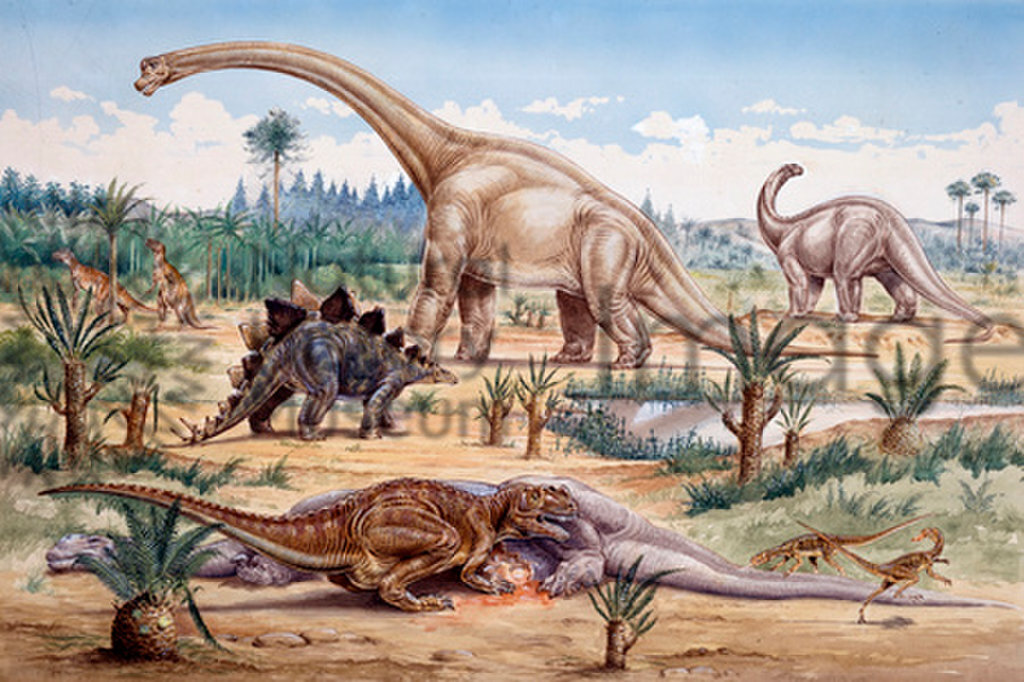

Among the most iconic dinosaurs that ever walked the Earth, Brachiosaurus stands tall with its distinctive upright posture and extraordinarily long neck. This massive sauropod roamed the late Jurassic landscape approximately 154-153 million years ago, leaving paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts fascinated by its unique adaptations and lifestyle. Named for its notably long forelimbs (the name means “arm lizard”), Brachiosaurus represents one of evolution’s most remarkable experiments in size and feeding strategy. As we explore this magnificent creature’s biology, habitat, and significance to paleontology, we’ll uncover how this gentle giant managed to become one of the most successful herbivores of its time, and why its unusual body plan continues to capture scientific interest today.

The Discovery and Naming of Brachiosaurus

Brachiosaurus was first discovered in 1900 by paleontologist Elmer S. Riggs in the Morrison Formation of western Colorado. The initial specimen consisted of a partial skeleton including vertebrae, ribs, and limb bones, providing enough evidence for Riggs to recognize it as something extraordinary. In 1903, he formally named the dinosaur Brachiosaurus altithorax, with “brachio” meaning “arm” and “saurus” meaning “lizard,” referencing its unusually long forelimbs compared to its hindlimbs. The species name “altithorax” translates to “deep chest,” noting another distinctive feature of this sauropod. Riggs’ discovery was revolutionary, as it represented one of the largest land animals known to science at that time, challenging previous conceptions about the physical limitations of terrestrial creatures. The finding sparked considerable scientific interest that continues to this day, with additional discoveries helping to refine our understanding of this remarkable dinosaur.

Physical Characteristics and Size

Brachiosaurus represents one of the most massive dinosaurs ever discovered, with estimates suggesting it reached lengths of 85 feet (26 meters) and heights of up to 40-50 feet (12-15 meters) – comparable to a modern four-story building. Unlike many other sauropods that had relatively level backs, Brachiosaurus featured a distinctly upward-sloping back due to its longer forelimbs than hindlimbs, giving it a giraffe-like posture. Weight estimates vary, but most paleontologists believe adult specimens weighed between 30-80 tons. The skull of Brachiosaurus was relatively small compared to its massive body, featuring large nasal openings and peg-like teeth adapted for stripping vegetation. One of its most distinctive features was the high-crested skull, with nostrils positioned near the top of the head, which initially led scientists to speculate about possible trunk-like structures, though this theory has since been reconsidered. The overall proportions of Brachiosaurus reflect its specialized feeding strategy and contribute to its iconic status in dinosaur paleontology.

The Unique Neck Adaptation

The neck of Brachiosaurus stands as one of its most remarkable adaptations, estimated to have been approximately 30 feet (9 meters) long. This extraordinary structure comprised 13 elongated cervical vertebrae, each modified with weight-reducing hollows while maintaining structural strength through internal struts and chambers – a feature known as pneumaticity. Recent research on sauropod necks indicates they were supported by complex ligaments and muscles that helped maintain their position without excessive muscular effort. Contrary to earlier beliefs that Brachiosaurus could raise its neck vertically like a modern giraffe, biomechanical studies suggest the neck likely had a more limited range of motion, capable of sweeping through approximately 90 degrees. The vertebrae articulation would have allowed for excellent lateral movement and moderate vertical flexibility, optimized for efficient high-browsing. This neck adaptation represents an evolutionary solution to accessing food sources unavailable to other contemporary herbivores, creating an ecological niche that contributed significantly to the success of these massive dinosaurs during the Jurassic period.

Evolutionary History and Related Species

Brachiosaurus belongs to the family Brachiosauridae within the larger group of sauropod dinosaurs, which evolved during the Middle Jurassic period approximately 170 million years ago. This family is characterized by their upright posture, longer forelimbs than hindlimbs, and high-browsing adaptations. The closest relatives to Brachiosaurus include Giraffatitan from Africa (once classified as a Brachiosaurus species), Lusotitan from Portugal, and Vouivria from France. Phylogenetic studies indicate that brachiosaurids evolved from earlier sauropods as part of the radiation of neosauropods, developing their distinctive body proportions in response to specific ecological opportunities. Their evolutionary success is evidenced by their widespread distribution across multiple continents during the Late Jurassic. However, while many sauropod lineages continued through the Cretaceous period, true brachiosaurids appear to have declined by the Early Cretaceous, suggesting changes in vegetation patterns or increased competition from other dinosaur groups may have affected their specialized ecological niche. This evolutionary history demonstrates the remarkable adaptability of sauropod dinosaurs across different environments and time periods.

Feeding Strategy and Diet

Brachiosaurus developed a highly specialized feeding strategy as a high-level browser, capable of reaching vegetation up to 40-50 feet above ground level – heights inaccessible to most other herbivores of its time. This ability to exploit elevated food sources gave Brachiosaurus a significant competitive advantage, allowing it to avoid direct competition with low-browsing dinosaurs. Its diet likely consisted primarily of conifers, ginkgoes, cycads, and early flowering plants that dominated the Jurassic landscape. The peg-like teeth of Brachiosaurus were adapted for stripping leaves rather than chewing, suggesting it processed food minimally before swallowing. Studies of tooth wear patterns indicate rapid tooth replacement, with new teeth developing every 1-2 months to compensate for wear from constant feeding. Based on body size and metabolic estimates, paleontologists calculate that an adult Brachiosaurus would have needed to consume hundreds of pounds of plant material daily to sustain itself. This intensive feeding behavior would have made these dinosaurs significant agents of ecological change, potentially altering forest structures and plant distributions throughout their range.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Brachiosaurus fossils have primarily been discovered in the Morrison Formation of western North America, an extensive sedimentary deposit spanning from New Mexico to Montana and from Utah to Oklahoma. During the Late Jurassic period, this region was characterized by a seasonal semi-arid climate with distinct wet and dry periods, creating a mosaic of forests and open woodlands along river systems. The environment supported diverse vegetation, including conifer forests, fern prairies, and primitive flowering plants that provided ample food for these massive herbivores. Beyond North America, remains attributed to the genus or closely related forms have been reported from Tanzania, Algeria, and potentially Portugal, suggesting a much wider distribution than initially recognized. These geographic findings indicate that brachiosaurids were successful across multiple continents, likely occupying similar ecological niches in diverse Jurassic ecosystems. The widespread distribution of these massive dinosaurs offers valuable insights into Jurassic paleogeography and the connections between landmasses during a time when the supercontinent Pangaea was continuing to fragment into separate continental landmasses.

Growth and Development

The growth pattern of Brachiosaurus represents one of the most rapid developmental trajectories known among vertebrates, transforming from meter-long hatchlings to massive adults over several decades. Studies of bone microstructure from sauropod dinosaurs reveal growth rings (similar to tree rings) that indicate these animals grew continuously but at different rates throughout their lives. During early development, juvenile Brachiosaurus likely experienced rapid growth rates of up to 5,000 pounds per year, helping them quickly outgrow potential predation risk. As they approached maturity, growth rates slowed but continued for many years, suggesting these dinosaurs may have reached reproductive maturity before attaining maximum size. Complete skeletal fusion, indicating full maturity, appears to have occurred when individuals were in their third or fourth decades of life. The extended growth period of Brachiosaurus represents an evolutionary strategy balancing the advantages of massive adult size with the need to reach reproductive maturity within a reasonable timeframe. This remarkable growth trajectory helps explain how sauropods achieved their extraordinary dimensions while maintaining viable populations across millions of years.

Locomotion and Movement Patterns

Despite its enormous size, Brachiosaurus was fully terrestrial and capable of efficient, if slow-paced, locomotion. Biomechanical studies of its unusual body proportions indicate that Brachiosaurus moved with a distinctive gait, with the longer forelimbs creating a sloped back that affected its center of gravity. Trackway evidence from related sauropods suggests these dinosaurs typically moved at walking speeds of 3-5 mph (5-8 km/h), though they may have been capable of faster movement for short durations when necessary. The columnar limbs of Brachiosaurus functioned like support pillars, distributing its massive weight effectively while requiring minimal muscular effort to maintain posture. Analysis of the limb bones shows extensive adaptation for weight-bearing, including thick cortical bone and internal structures optimized for compressive forces. When moving, Brachiosaurus would have kept all four feet on the ground for most of its stride cycle, creating a stable platform that maintained balance. This locomotive efficiency allowed these giants to undertake the seasonal migrations likely necessary to find adequate food supplies throughout the year, though they probably avoided difficult terrain like steep slopes or densely forested areas where maneuverability would have been compromised.

Social Behavior and Herd Structure

While direct evidence of Brachiosaurus social behavior remains limited, paleontologists have developed theories based on trackway evidence, bone bed accumulations of related sauropods, and comparisons with modern large herbivores. Multiple sauropod trackways discovered in parallel suggest these dinosaurs may have traveled in loose herds or family groups, potentially for protection against predators and efficient foraging. Age segregation appears likely, with juveniles potentially forming separate groups from adults, similar to patterns observed in modern elephants. The energy requirements and feeding impacts of adult Brachiosaurus would have necessitated regular movement through their habitats, making permanent herds impractical in most environments. Instead, fluid social groupings probably formed and dissolved based on seasonal conditions, reproductive status, and resource availability. During breeding seasons, adults may have congregated in specific areas, potentially explaining some fossil accumulations of large sauropods. This social flexibility would have provided adaptive advantages, allowing Brachiosaurus to respond to changing environmental conditions while maintaining some benefits of group living when advantageous.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The reproductive strategy of Brachiosaurus likely followed patterns observed in other sauropod dinosaurs, with females laying multiple eggs in sequential nesting events. Based on discoveries of related sauropod nesting sites, Brachiosaurus probably excavated shallow depressions for egg-laying, potentially in colonial nesting grounds where many females gathered seasonally. Each nest would have contained 20-40 eggs arranged in carefully organized patterns, with eggs measuring approximately 8-10 inches (20-25 cm) in diameter. The large egg size represented an evolutionary compromise, allowing for sufficiently developed hatchlings while still maintaining viable shell thickness. Hatchlings emerged relatively precocial (well-developed), capable of independent movement and basic feeding shortly after hatching. Unlike many modern reptiles, evidence suggests sauropods provided minimal parental care, with juveniles likely forming protective groups separate from adults. The tremendous size disparity between hatchlings and adults – representing a 25,000-fold increase in mass over a lifetime – required different survival strategies at different life stages. This reproductive approach, prioritizing high numbers of independent offspring, proved highly successful for sauropod dinosaurs throughout their 140-million-year evolutionary history.

Predators and Defense Mechanisms

Despite their enormous size, Brachiosaurus and other sauropods faced predation risk, particularly from large theropod dinosaurs like Allosaurus and Torvosaurus that shared their Morrison Formation ecosystem. Adult Brachiosaurus would have been formidable targets due to their sheer size, with few predators capable of successfully attacking a healthy individual. Size itself functioned as the primary defense mechanism, with most predators focusing on juveniles, sick, or elderly individuals that presented less risk. If threatened, Brachiosaurus could potentially have used its massive tail as a defensive weapon, though with less specialization for this purpose than some other sauropods like Diplodocus. Group living likely provided additional protection through increased vigilance and the “selfish herd” effect, where individuals reduced their personal risk by positioning themselves within groups. The substantial size difference between hatchling and adult Brachiosaurus created vulnerability for younger individuals, explaining why juvenile mortality rates were likely high. Fossil evidence from related sauropods shows tooth marks and feeding traces from large theropods, confirming that even these giants were incorporated into the Jurassic food web as prey under certain circumstances.

Paleoenvironmental Impact

As megaherbivores, Brachiosaurus and other sauropods functioned as ecosystem engineers, significantly impacting their environments through their feeding and movement patterns. The intensive browsing behavior of Brachiosaurus would have shaped forest canopy structure, potentially creating clearings and affecting plant succession patterns throughout their range. Based on modern ecological models, an adult Brachiosaurus likely consumed 200-400 pounds (90-180 kg) of plant material daily, translating to substantial vegetation removal across their habitats. Their movement through forests would have created pathways utilized by other animals, while their massive bodies trampled undergrowth in heavily used areas. Perhaps most significantly, sauropods served as mobile nutrient distribution systems, consuming vegetation in one area and depositing nutrient-rich dung elsewhere. Modern studies of elephants demonstrate how large herbivore dung significantly enhances soil fertility and plant growth; the much larger sauropods would have magnified this effect. Additionally, upon death, each Brachiosaurus carcass represented a massive nutrient pulse of several tons of organic matter, supporting decomposers and scavengers while enriching local soils. This ecological role highlights how these giants functioned as keystone species within Jurassic ecosystems, shaping environmental patterns that affected countless other organisms.

Cultural Impact and Representations

Since its scientific description in 1903, Brachiosaurus has captured public imagination as an iconic representation of dinosaur gigantism. Its distinctive silhouette has appeared in numerous scientific illustrations, museum displays, and popular media, including its memorable appearance in the original Jurassic Park film, where it introduced millions of viewers to the concept of sauropod dinosaurs. Museum mounts of Brachiosaurus, particularly the famous specimen at Chicago’s Field Museum (now reclassified as Giraffatitan), have become cultural landmarks that help visualize the extraordinary scale of these animals for public audiences. The dinosaur has featured prominently in educational materials, becoming a standard entry point for discussions about the Jurassic period, dinosaur diversity, and the physical limitations of terrestrial animals. Brachiosaurus has also influenced artistic and architectural expressions, inspiring designs that explore themes of monumental scale and prehistoric life. This cultural prominence extends beyond entertainment value, as Brachiosaurus frequently serves as an ambassador species that attracts public interest in paleontology, evolution, and natural history, highlighting the important role these ancient creatures play in contemporary scientific education and appreciation.

Scientific Debates and Ongoing Research

Brachiosaurus continues to stand at the center of several active scientific debates within paleontology. One persistent controversy involves the relationship between the North American Brachiosaurus and the African Giraffatitan, with some researchers maintaining they represent separate genera while others argue for closer classification. Debates also continue regarding the neck posture and flexibility of brachiosaurids, with competing biomechanical models suggesting different possible ranges of motion and feeding capabilities. The physiological mechanisms that allowed these massive animals to function – particularly questions about metabolic rates, thermoregulation, and cardiovascular systems – remain active areas of investigation. Modern research increasingly employs advanced technologies like CT scanning to examine internal bone structures, finite element analysis to test biomechanical hypotheses, and stable isotope analysis to investigate diet and habitat preferences. The discovery of new brachiosaurid material, particularly from less-explored regions, continues to refine our understanding of their diversity and evolutionary relationships. These ongoing scientific discussions demonstrate how Brachiosaurus remains relevant to contemporary paleontological research, with each new study adding to our understanding