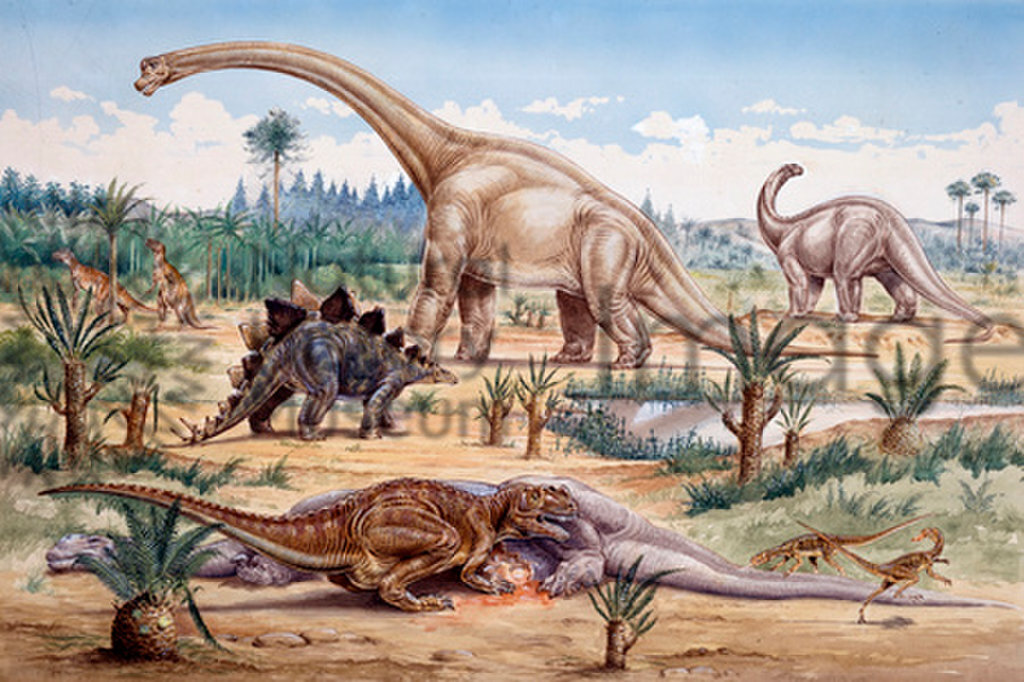

The Mesozoic Era witnessed some of Earth’s most magnificent creatures—none more awe-inspiring than the massive sauropod dinosaurs that dominated the landscape. Among these titans, Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus stand out as iconic representatives of different sauropod evolutionary paths. Though both were enormous herbivores with long necks, their anatomical differences, habitats, and lifestyles tell a fascinating story of adaptation and specialization. This article explores how these two giants differed in structure, behavior, and ecological niche, revealing the remarkable diversity that existed even among the largest land animals ever to walk the Earth.

The Sauropod Family Tree: Different Branches of Giants

Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus belong to distinct families within the sauropod lineage, representing different evolutionary adaptations to their Jurassic world. Brachiosaurus was a member of the Brachiosauridae family, characterized by its front-heavy build and giraffe-like posture. Diplodocus, meanwhile, belonged to the Diplodocidae family, known for their extremely elongated body and whip-like tails.

These taxonomic differences reflect millions of years of separate evolution, with their last common ancestor living in the Early to Middle Jurassic period, approximately 170-165 million years ago. The divergent body plans of these two sauropods demonstrate how evolution produced varied solutions to the challenge of growing to enormous sizes while still functioning effectively as living animals.

Time Travelers: When These Giants Walked the Earth

These magnificent dinosaurs didn’t share the exact same time period, though both thrived during parts of the Jurassic period. Brachiosaurus fossils date primarily to the Late Jurassic epoch, approximately 154-153 million years ago, with the most famous specimens coming from the Morrison Formation in North America. Diplodocus lived slightly later in the Late Jurassic, with fossils dating between 154-152 million years ago, also predominantly found in the Morrison Formation.

This slight temporal difference, though small on a geological scale, meant that these two giants might have inhabited slightly different environments as the ancient landscape gradually transformed over time. The fossil record indicates that Diplodocus species persisted for a longer evolutionary timespan than the currently known Brachiosaurus species, suggesting possible differences in their adaptability to changing conditions.

Size Matters: Comparing Dimensions

When comparing their physical dimensions, both dinosaurs were colossal but with notable differences. Brachiosaurus stood approximately 40-50 feet (12-15 meters) tall at the shoulder and reached lengths of 85 feet (26 meters), with weight estimates between 35-58 tons. Its most striking feature was its extreme height, with its head potentially reaching up to 40-50 feet above the ground.

Diplodocus, while not as tall, was considerably longer, stretching 80-115 feet (24-35 meters) from nose to tail, though weighing less at 10-16 tons. This dramatic weight difference, despite Diplodocus’s greater length, reflects fundamental differences in body construction, with Diplodocus possessing a much more gracile build and lighter skeletal structure. The massive size of both dinosaurs represents the upper limit of what’s physically possible for land animals, with each approaching these limits in different ways.

Neck and Head: Different Designs for Different Diets

The necks of these dinosaurs showcase some of their most striking anatomical differences, directly tied to their feeding strategies. Brachiosaurus had a relatively shorter but more robust upward-angled neck that allowed it to browse vegetation at tremendous heights, similar to modern giraffes. Its neck vertebrae were shorter but stronger, supporting powerful muscles needed to hold the neck in its characteristic upright position.

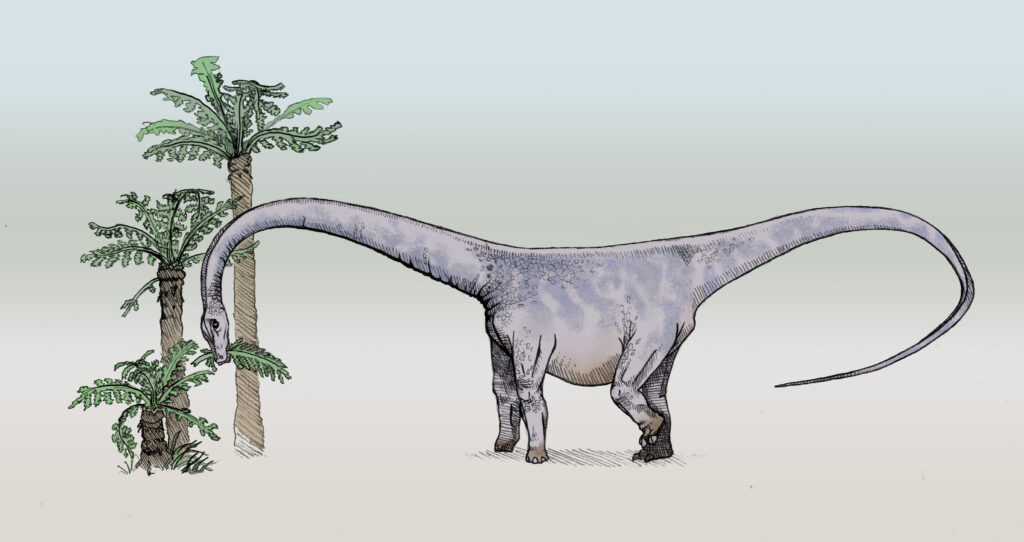

Diplodocus, by contrast, possessed an extraordinarily long, horizontally oriented neck with up to 15 extremely elongated vertebrae, designed for sweeping across broad areas of vegetation at lower to middle heights. The head morphology further reflected their dietary specializations—Brachiosaurus had a broader, more powerful skull with spoon-shaped teeth for processing tougher plant material, while Diplodocus had a longer, more slender skull with pencil-like teeth at the front, perfect for stripping leaves from branches with a comb-like motion.

Posture and Proportions: Front-Heavy vs. Balanced

The overall body proportions of these sauropods reveal fundamentally different approaches to their massive size. Brachiosaurus was distinctly front-heavy with forelimbs substantially longer than its hindlimbs, creating its characteristic sloped back and high-shouldered appearance. This unusual configuration, rare among quadrupedal animals, enabled its distinctive high-browsing feeding strategy but required powerful shoulder and chest muscles to support the tremendous weight. Diplodocus maintained more balanced proportions with slightly shorter forelimbs than hindlimbs and a more horizontal spinal alignment.

Its center of gravity was positioned differently, with weight more evenly distributed along its extraordinarily long body. These profound differences in body proportion weren’t merely aesthetic but represented specialized adaptations that influenced everything from locomotion to feeding capacity, demonstrating how evolution shaped these giants for different ecological niches despite their superficial similarities as long-necked herbivores.

Tail Tales: Length and Function

The tails of these dinosaurs tell a story of dramatically different evolutionary adaptations and possible behaviors. Diplodocus possessed an extraordinarily long, whip-like tail that could extend up to half its total body length, ending in a thin section of vertebrae that some paleontologists believe could have been cracked like a whip, potentially creating supersonic sounds for communication or defense. This remarkable adaptation contained up to 80 vertebrae, some with unique “double beam” structures that provided both flexibility and strength.

Brachiosaurus, in contrast, had a much shorter, more robust tail that primarily served as a counterbalance to its massive neck rather than as a specialized tool or weapon. The tail vertebrae of Brachiosaurus lacked the extreme elongation seen in Diplodocus, instead maintaining a more consistent size throughout the tail length. These differences in tail morphology reflect not only their different body plans but also potentially different social behaviors and defensive strategies against the large predators of their time.

Feeding Strategies: High Browser vs. Mid-Level Sweeper

The distinct body structures of these titans directly translated to different feeding approaches that minimized competition despite sharing some habitats. Brachiosaurus was the quintessential high browser, capable of reaching foliage at heights of up to 40-50 feet above ground level—vegetation that remained inaccessible to most other herbivores of the Late Jurassic. Its upright posture and considerable height allowed it to exploit food sources in the canopies of tall conifers and ginkgo trees that dominated the Jurassic landscape.

Diplodocus utilized a completely different strategy, using its exceptionally long neck in a more horizontal position to sweep across vast areas of mid and lower-height vegetation without needing to move its massive body. This feeding strategy, sometimes called “lateral browsing,” allowed Diplodocus to efficiently harvest ferns, cycads, and lower-growing plants while expending minimal energy. These complementary feeding adaptations allowed these massive herbivores to coexist without direct competition for the same food resources, demonstrating an ecological principle known as niche partitioning.

Skeletal Architecture: Built for Different Functions

Examining the internal skeletal structures reveals sophisticated engineering solutions that allowed these giants to function despite their tremendous size. Diplodocus evolved highly specialized vertebrae with complex internal chambers and strut-like supports that created an incredibly lightweight yet strong spinal column. These vertebrae contained elaborate air spaces (pneumatic cavities) that significantly reduced weight while maintaining structural integrity—a biological example of weight-saving design that modern engineers still admire.

Brachiosaurus, needing greater strength to support its more vertical posture, developed thicker, more robust vertebrae with different pneumatic structures optimized for compressive strength rather than extreme elongation. The limb bones show equally dramatic differences—Brachiosaurus possessed thick, column-like limbs with solid construction to support its massive front-heavy weight, while Diplodocus developed more slender limbs with proportionally thinner walls, sufficient for its lighter body mass but less capable of supporting the extreme weight of a Brachiosaurus-type body.

Habitat Preferences: Environmental Adaptations

Fossil evidence and environmental reconstructions suggest these sauropods may have preferred slightly different habitats within the Late Jurassic landscape. Brachiosaurus fossils are typically associated with more heavily forested environments with abundant tall conifers and tree ferns that would have provided the high-growing vegetation its specialized anatomy was designed to reach.

Its distribution appears somewhat more limited to areas that could support larger trees and more abundant vegetation. Diplodocus fossils, by contrast, are found across a broader range of environments, including more open woodlands and savanna-like settings where its ability to cover large areas efficiently while browsing would have been advantageous.

The Morrison Formation, where both dinosaurs have been discovered, represented a diverse mosaic of habitats during the Late Jurassic, from river floodplains to drier uplands, allowing these differently adapted giants to thrive in complementary ecological zones. Their different environmental tolerances likely reduced direct competition and allowed both types to flourish during this period of dinosaur gigantism.

Movement and Locomotion: Speed and Agility Differences

Despite their enormous size, these sauropods were not immobile behemoths but active animals with distinct locomotion capabilities. Biomechanical studies suggest Diplodocus, with its lighter build and more horizontal posture, could have achieved walking speeds of approximately 9-14 miles per hour (15-23 km/h), making it surprisingly fast for its size. Its extremely long body and tail would have moved in a sinuous, almost snake-like motion during walking, with the tail potentially serving as a dynamic counterbalance.

Brachiosaurus, being significantly heavier and front-loaded, likely moved more slowly and deliberately, with estimated speeds of 5-8 miles per hour (8-13 km/h). Its unusual front-heavy design would have required a unique gait, with studies suggesting it may have moved both forelimbs forward before moving its hindlimbs—a gait unlike most modern quadrupeds. The massive footprints of Brachiosaurus indicate it placed tremendous pressure on the ground with each step, potentially over 75 pounds per square inch (5.3 kg/cm²), leaving distinctive depressions in the soft Jurassic soils that occasionally fossilized into trackways that paleontologists study today.

Reproduction and Growth: Life History Contrasts

Both sauropods laid eggs, but differences in their reproductive strategies and growth patterns may have existed based on what we understand about their anatomical differences. Fossil evidence suggests Diplodocus laid numerous relatively small eggs (compared to adult size) in ground-nesting colonies, potentially investing less energy in each individual offspring but producing more numerous clutches. Growth ring studies from Diplodocus bones indicate they grew extraordinarily rapidly, potentially reaching adult size within 10-15 years—an astonishing growth rate for such a large animal.

Brachiosaurus reproduction is less well-documented due to fewer fossil discoveries, but its massive adult size and different skeletal structure suggest it might have produced fewer but possibly larger eggs, with a somewhat slower growth trajectory to accommodate its more massive frame and different proportions. The tremendous energy requirements of growing to such massive sizes would have shaped the reproductive strategies of both dinosaurs, forcing evolutionary compromises between offspring number, size, and parental investment that likely differed between these two sauropod lineages.

Scientific Discovery and Cultural Impact

The scientific and cultural legacies of these two giants have followed fascinatingly different trajectories since their initial discoveries. Brachiosaurus was first described in 1903 by paleontologist Elmer Riggs from specimens collected in Colorado, but achieved worldwide fame through its prominent appearance in Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film “Jurassic Park,” where its towering form and distinctive profile created one of cinema’s most iconic dinosaur moments.

Diplodocus has perhaps the more remarkable scientific history, with fossils first described by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878 and later becoming one of the most widely displayed dinosaurs in the world thanks to industrialist Andrew Carnegie, who commissioned replicas of the famous “Diplodocus carnegii” specimen for museums across Europe and South America in the early 1900s.

These “Dippy” displays introduced millions of people to dinosaur science decades before most other dinosaur specimens became widely known. Both dinosaurs continue to evolve in scientific understanding, with recent research revising aspects of their anatomy, posture, and ecological roles based on new fossil evidence and analytical techniques.

Modern Scientific Debates: Ongoing Questions

Contemporary paleontologists continue debating several aspects of these dinosaurs’ biology and behavior, with new discoveries constantly refining our understanding. One major ongoing discussion concerns the neck posture of Diplodocus, with some researchers arguing it held its neck more vertically than traditionally depicted, while others maintain evidence supports a more horizontal orientation based on vertebral joint structures.

For Brachiosaurus, significant debate surrounds its respiratory system and the implications of its unusual body proportions for blood pressure regulation—maintaining blood flow to a brain positioned so high above the heart would have required specialized cardiovascular adaptations unlike any living animal today. Soft tissue reconstruction remains highly speculative for both dinosaurs, including questions about potential throat pouches, skin textures, and coloration patterns.

The limited fossil record for juvenile specimens of both species also leaves questions about their early development and potential parental care behaviors largely unanswered. These ongoing scientific conversations demonstrate how these long-extinct giants continue to stimulate research and challenge our understanding of biological possibilities.

Conclusion

Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus represent remarkable evolutionary experiments in gigantism, each solving the challenges of massive size in distinctly different ways. From their contrasting skeletal structures and postures to their complementary feeding strategies and habitat preferences, these sauropods showcase the incredible diversity that existed even among the largest dinosaurs. Their differences weren’t merely variations on a theme but fundamental adaptations that allowed them to exploit different environmental opportunities within the same Jurassic ecosystems.

As our scientific understanding continues to evolve through new discoveries and analytical techniques, these magnificent giants continue to captivate both researchers and the public, serving as ambassadors from an ancient world where the boundaries of biological possibility were pushed to extremes we can still barely comprehend today.