The illicit trade of fossils represents a significant threat to scientific knowledge and cultural heritage worldwide. Each year, countless paleontological specimens are illegally excavated and sold through black market channels, disappearing into private collections and depriving scientists and the public of valuable insights into the history of our planet. As awareness of this issue grows, countries are increasingly seeking legal avenues to reclaim these stolen treasures. This complex intersection of science, law, international relations, and cultural heritage presents unique challenges that continue to evolve as nations develop more sophisticated approaches to fossil protection and repatriation.

The Scale of the Fossil Black Market

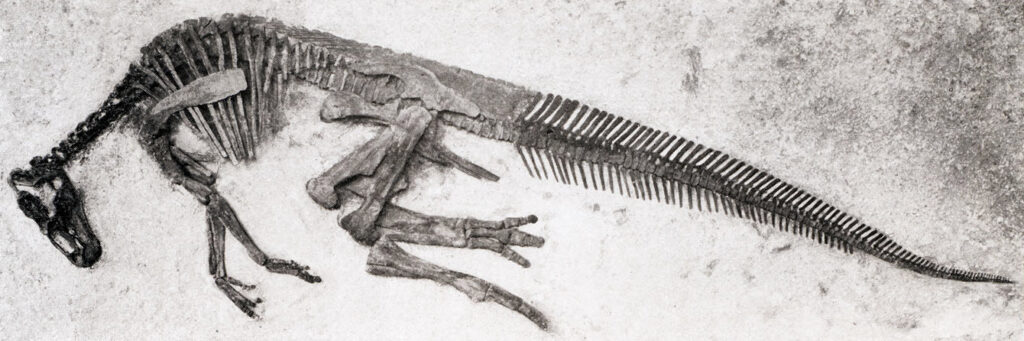

The fossil black market operates as a shadowy global enterprise estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually. High-profile specimens, such as complete dinosaur skeletons, can fetch prices exceeding $1 million, creating powerful financial incentives for illegal excavation and smuggling. Unlike the trade in wildlife or cultural artifacts, which has received significant international attention, the fossil black market often operates with less scrutiny and enforcement. Countries with rich paleontological resources but limited infrastructure for protection, such as Mongolia, China, Brazil, and Morocco, are particularly vulnerable to fossil poaching. The illegal trade typically begins with unauthorized excavations in remote areas, followed by smuggling across borders with falsified documentation or deliberate misidentification of specimens to evade detection by customs authorities.

Legal Frameworks for Fossil Protection

The legal protection of fossils varies dramatically around the world, creating a patchwork of regulations that can be exploited by traffickers. Some nations, including Mongolia, China, and Argentina, have enacted comprehensive laws declaring all fossils within their territories as state property, making any unauthorized collection or export illegal by definition. Other countries employ more nuanced approaches, regulating fossil collection through permit systems or restricting only certain categories of specimens. The United States represents a particularly complex case, where fossil protection depends largely on land ownership status—fossils found on public lands are federally protected, while those discovered on private property typically belong to the landowner. This inconsistency in legal frameworks creates significant challenges for international cooperation in fossil protection and repatriation efforts, as what constitutes illegal activity in one jurisdiction may be perfectly legal in another.

International Treaties and Agreements

Unlike cultural artifacts, which are protected under the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, fossils lack a dedicated, comprehensive international treaty. This creates significant hurdles for countries seeking to reclaim specimens sold on the black market. Some nations have successfully leveraged existing agreements like the UNESCO convention by classifying fossils as cultural property, though this approach is not universally accepted. Regional agreements, such as MERCOSUR’s protocol on cultural heritage protection in South America, sometimes include provisions that can apply to paleontological specimens. Bilateral agreements between specific countries have also proven effective in some cases, particularly between nations with significant paleontological resources and those with major fossil markets. The absence of a specialized international framework specifically addressing fossil trafficking remains a substantial obstacle to coordinated global action against the illicit fossil trade.

Notable Repatriation Success Stories

Despite the challenges, several countries have achieved remarkable successes in reclaiming fossils sold through black market channels. Mongolia’s recovery of numerous illegally exported dinosaur specimens stands as a prominent example, including the high-profile case of a Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton that was returned after being sold at auction in New York for over $1 million. The United States has assisted Brazil in recovering numerous pterosaur fossils that were smuggled out of the country and offered for sale at international fossil fairs. Argentina successfully secured the return of dinosaur eggs and other specimens from various international collectors after demonstrating their illicit origin. China has gradually recovered numerous feathered dinosaur specimens that had been illegally exported during the fossil boom of the 1990s and early 2000s. These successes typically involve extensive diplomatic negotiations, legal proceedings, and sometimes the cooperation of academic institutions or individual collectors who acquired specimens without knowledge of their illegal provenance.

Diplomatic and Legal Strategies for Reclamation

Countries pursuing the return of illegally exported fossils typically employ a multi-faceted approach combining diplomatic pressure, legal action, and public awareness campaigns. Formal diplomatic requests through established channels represent the first step, often followed by more assertive measures if initial approaches fail to yield results. Legal strategies frequently involve civil forfeiture proceedings in the country where the fossil is currently located, requiring the source country to provide substantial evidence of the specimen’s illegal excavation or export. Some nations have formed specialized legal teams with expertise in both international law and paleontology to build compelling cases for repatriation. Public pressure can play a crucial role, as museums and reputable auction houses increasingly face reputational risks if they handle specimens of questionable provenance. These combined approaches have gradually increased the success rate of fossil repatriation efforts, though they remain resource-intensive and time-consuming.

Challenges in Proving Provenance

One of the most significant obstacles in reclaiming black market fossils is establishing their precise origin and the circumstances of their excavation. Unlike manufactured cultural artifacts, which may have distinctive stylistic features linking them to specific regions or cultures, fossils can sometimes be difficult to conclusively associate with a particular geographic location based solely on their physical characteristics. Sediment analysis can sometimes provide evidence of origin, but this requires access to the specimen and comparative geological samples. Documentation for illegally excavated fossils is often deliberately falsified or simply nonexistent, creating significant evidentiary challenges. The passage of time further complicates matters, as fossils that entered private collections decades ago may have changed hands multiple times, obscuring their original provenance. Countries with more detailed geological surveys and fossil inventories generally have greater success in definitively establishing the origin of specimens and supporting repatriation claims.

The Role of Museums and Academic Institutions

Museums and universities play a complex and sometimes contradictory role in the fossil trade and repatriation efforts. These institutions have historically been among the primary markets for commercially collected fossils, occasionally acquiring specimens of questionable provenance that later became subjects of repatriation claims. However, many museums have adopted increasingly stringent acquisition policies in recent decades, requiring thorough documentation of legal origin before adding specimens to their collections. Academic institutions frequently provide crucial scientific expertise to support repatriation efforts, helping to authenticate specimens and verify their geographic origins. Several major museums have voluntarily returned fossils after determining they were likely exported illegally, sometimes without formal legal proceedings. Museum associations in North America and Europe have developed ethical guidelines specifically addressing fossil acquisition, though adherence varies considerably among institutions. This evolving ethical landscape has significantly influenced the market for high-profile specimens, reducing legitimate outlets for illegally collected fossils.

Private Collectors and the Repatriation Process

The relationship between private fossil collectors and repatriation efforts presents particular challenges and opportunities. Some collectors unknowingly acquire illegally exported specimens, while others deliberately seek out black market fossils to avoid legal restrictions and potentially higher prices in legitimate markets. When countries pursue repatriation, collectors may face financial losses if they surrender specimens, creating incentives to resist repatriation claims or transfer fossils to jurisdictions with weaker enforcement. However, some private collectors have voluntarily returned specimens after learning of their illegal provenance, particularly when countries pursue goodwill-based approaches rather than punitive measures. Several countries have implemented amnesty programs encouraging the voluntary surrender of illegally acquired fossils without legal consequences, achieving mixed results. The increasing legal and reputational risks associated with collecting illegally excavated fossils have gradually influenced collector behavior, though the high-end market for exceptional specimens continues to drive significant black market activity.

Digital Technologies and Fossil Tracking

Emerging technologies are transforming how countries identify and track fossils that enter illegal trade channels. Advanced imaging techniques, including photogrammetry and CT scanning, allow for the creation of detailed digital records of known specimens that can later be used for identification if they appear on the market. Blockchain and other digital ledger technologies are being explored as potential tools for creating tamper-proof records of legally excavated fossils, potentially distinguishing them from illicitly obtained specimens. Artificial intelligence applications can analyze online auction listings and social media to identify potentially illegal fossil sales, helping authorities target enforcement efforts. DNA analysis of subfossil material (specimens not fully fossilized) can sometimes provide evidence linking specimens to specific regions. These technological approaches are particularly valuable for countries with limited resources for physical monitoring of fossil sites and borders, allowing more effective targeting of enforcement efforts and building stronger cases for repatriation when illegal specimens are identified.

Economic and Scientific Impacts of Fossil Trafficking

The black market fossil trade inflicts significant economic and scientific damage on source countries beyond the loss of the specimens themselves. Many fossil-rich nations have developed or are developing paleontological tourism industries, which can provide sustainable economic benefits to local communities near significant fossil sites. The looting of these sites for the black market diminishes their scientific and educational value, reducing their potential as tourism destinations. From a scientific perspective, illegally excavated fossils typically lack crucial contextual information about their precise location and stratigraphic position, significantly diminishing their research value. Even when repatriated, these specimens have often been prepared using techniques that prioritize aesthetic appeal over scientific information preservation. Some countries have quantified these impacts when pursuing repatriation claims, arguing that compensation should consider not just the market value of specimens but also the broader economic and scientific losses resulting from their illegal excavation and export.

Preventative Measures and Local Engagement

Recognizing that preventing illegal fossil excavation is more effective than pursuing repatriation after the fact, many countries have implemented comprehensive protection strategies focused on local engagement. Community-based monitoring programs enlist residents near significant fossil sites as guardians, providing economic incentives for protection rather than participation in illegal excavation. Education initiatives highlight the scientific and cultural value of fossils, fostering local pride and ownership of paleontological heritage. Some nations have established legal commercial fossil collecting programs with strict oversight, creating legitimate economic opportunities that compete with black market incentives. Remote monitoring technologies, including satellite surveillance and drone patrols, help authorities detect unauthorized excavations in isolated areas. These preventative approaches require significant investment but have proven more cost-effective than the complex and uncertain process of pursuing repatriation after fossils have entered black market channels and crossed international borders.

Future Directions in Fossil Protection and Repatriation

The landscape of fossil protection and repatriation continues to evolve, with several promising developments on the horizon. Momentum is building for a specialized international agreement specifically addressing fossil trafficking, potentially modeled on existing frameworks for cultural property or endangered species. Digital certification systems for legally excavated fossils are advancing rapidly, with potential for widespread adoption within the next decade. Market countries are increasingly acknowledging responsibility for controlling imports of potentially illegal specimens, rather than placing the entire enforcement burden on source countries. Scientific journals and professional societies are adopting stricter policies regarding research on fossils of questionable provenance, reducing the academic incentives for working with potentially illegal specimens. These developments suggest a gradual shift toward more effective international cooperation in fossil protection, though significant challenges remain in harmonizing diverse national approaches to paleontological heritage and balancing scientific access with protection imperatives.

Conclusion: Balancing Preservation and Access

The reclamation of fossils sold on the black market represents a critical but challenging aspect of paleontological heritage protection. While countries have achieved notable successes in recovering illegally exported specimens, these efforts remain resource-intensive and uncertain. The most effective approaches combine robust legal frameworks, international cooperation, community engagement, and technological innovation. Looking forward, the greatest promise lies in preventative measures that protect fossils before they enter illegal trade channels, supported by clear international standards and cooperative enforcement. Ultimately, the goal extends beyond simple repatriation to the development of sustainable systems that preserve paleontological heritage while ensuring appropriate scientific access and educational benefits. As this field continues to develop, countries are increasingly recognizing that fossils represent a unique category of natural heritage requiring specialized approaches that balance national sovereignty with the global scientific significance of these irreplaceable windows into our planet’s past.