In the vast prehistoric landscapes of what is now Argentina, a peculiar dinosaur once roamed the southern continents during the Late Cretaceous period. Carnotaurus sastrei, with its distinctive bull-like horns and comically undersized forelimbs, stands as one of paleontology’s most fascinating predators. This unique theropod not only captured the imagination of scientists when it was discovered in 1984 but continues to intrigue dinosaur enthusiasts worldwide. Unlike many of its contemporaries, Carnotaurus presents a remarkable combination of features—powerful hind legs built for speed, an unusually short skull topped with prominent horns, and arms so reduced they appear almost vestigial. As we explore this remarkable creature, we’ll uncover how this specialized carnivore adapted to its environment and what its unusual anatomy tells us about dinosaur evolution in South America’s isolated ecosystems.

Discovery and Classification

Carnotaurus sastrei was discovered in 1984 by the renowned Argentine paleontologist José Bonaparte during an expedition to Patagonia. The remarkably complete skeleton, including an exceptionally preserved skull and extensive skin impressions, was unearthed from the La Colonia Formation in Chubut Province, Argentina. Dating to approximately 71 million years ago during the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, this find represented a significant breakthrough in our understanding of South American theropods. Bonaparte formally described and named the dinosaur in 1985, with “Carnotaurus” translating to “meat-eating bull” about its distinctive horns, and “sastrei” honoring Angel Sastre, the owner of the ranch where the fossil was discovered. Taxonomically, Carnotaurus belongs to the Abelisauridae family, a group of predatory dinosaurs that dominated the Southern Hemisphere during the Late Cretaceous after the earlier allosaurids declined.

Distinctive Skull and Horns

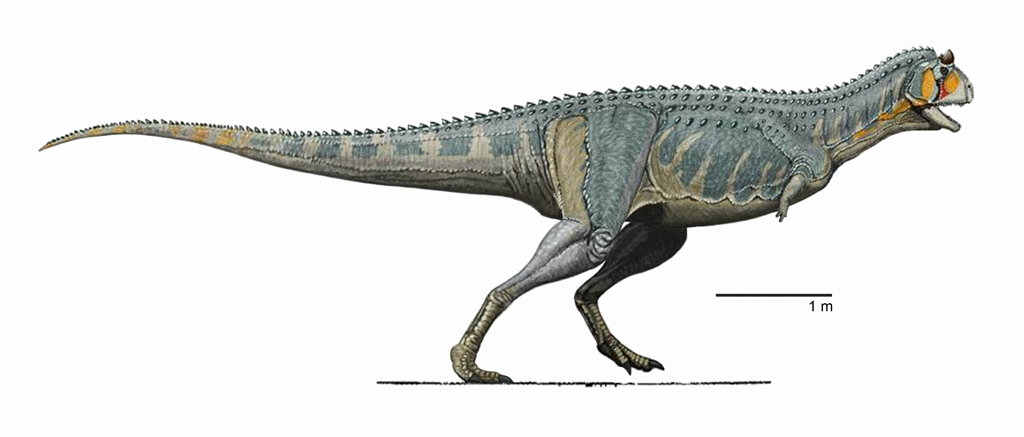

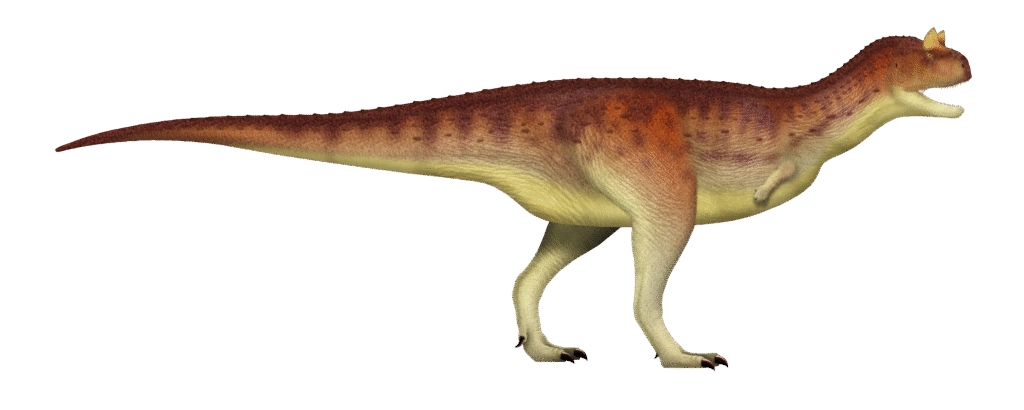

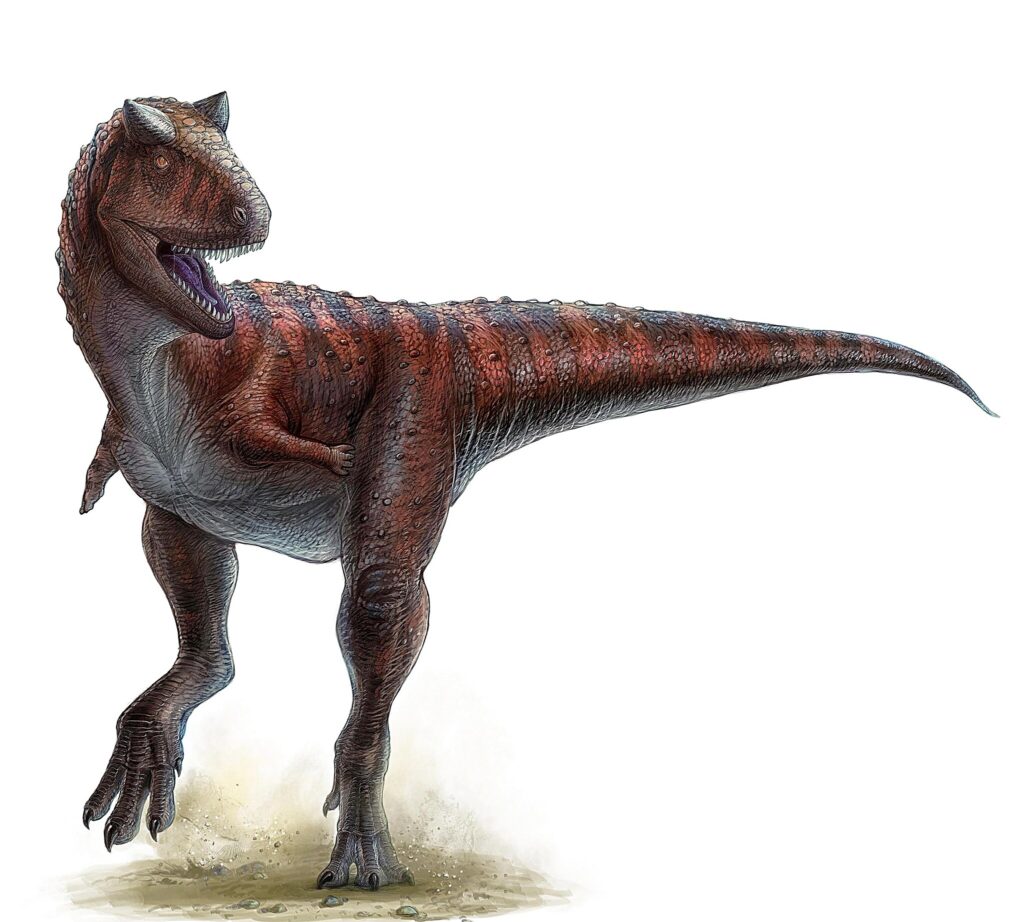

The most striking feature of Carnotaurus is undoubtedly its skull, which measures approximately 60 centimeters (2 feet) in length and possesses a unique morphology among theropod dinosaurs. Most notable are the two thick, bony horns that protrude above the eyes, extending upward and slightly outward like those of a modern bull. These horns, composed of extended brow bones (frontals), measure about 15 centimeters (6 inches) in length and were likely covered with a keratinous sheath in life, potentially making them even more prominent. The skull itself is unusually short and deep compared to other large theropods, with extremely reduced nasal openings and remarkably small, forward-facing eyes that provided some degree of binocular vision. The teeth of Carnotaurus were blade-like and serrated, though relatively small compared to its skull size, suggesting they were adapted for slashing rather than crushing prey. This distinctive cranial anatomy indicates Carnotaurus may have utilized its head in ways different from other predatory dinosaurs of its time.

The Mystery of the Tiny Arms

Perhaps the most perplexing aspect of Carnotaurus’s anatomy is its extraordinarily reduced forelimbs, which were even more diminutive relative to body size than those of the famous Tyrannosaurus rex. Each arm measured only about 30 centimeters (1 foot) in length, less than half the length of its skull, making them proportionally among the smallest of any known theropod dinosaur. These vestigial limbs featured four fingers, though they were fused and immobile, rendering them essentially non-functional for grasping prey or other typical forelimb activities. Paleontologists have proposed several theories to explain this extreme reduction, including the possibility that the arms were evolutionarily vestigial structures that had lost their function as the dinosaur’s hunting strategy came to rely more on its powerful jaws and strong legs. Another hypothesis suggests that the reduced arms decreased body weight at the front of the animal, improving its balance and speed. Whatever their purpose—or lack thereof—thereof-these diminutive appendages represent an extreme case of evolutionary specialization.

Speed and Locomotion

Carnotaurus possessed a body structure that strongly suggests it was built for speed, potentially making it one of the fastest large theropods of its time. Analysis of its leg proportions reveals a femur (thigh bone) that was shorter than the tibia (shin bone), a characteristic often associated with cursorial (running-adapted) animals. The metatarsals (foot bones) were also elongated, further supporting the hypothesis that Carnotaurus was an efficient runner. Muscle attachment sites on the tail vertebrae indicate powerful muscles that would have counterbalanced the animal during rapid movements and tight turns. Biomechanical studies suggest that Carnotaurus may have been capable of reaching speeds of up to 48-56 kilometers (30-35 miles) per hour, making it an effective pursuit predator in the open environments of Late Cretaceous Argentina. This speed advantage would have been crucial for hunting prey in the grassland-like habitats that were becoming increasingly common during this period, as forests receded due to climate change.

Skin Impressions and Appearance

The Carnotaurus fossil discovery included something extraordinarily rare—extensive skin impressions covering large portions of the animal’s body, providing unprecedented insight into the external appearance of this theropod. These impressions revealed that Carnotaurus possessed a covering of non-overlapping scales, averaging about 5 millimeters in diameter, with larger feature scales irregularly distributed among them. Interestingly, these scales did not show the presence of feathers, suggesting that, unlike some other theropods, Carnotaurus maintained a fully scaled integument. The skin along the sides of the body showed a distinctive pattern of larger, conical, bumpy scales arranged in vertical rows, creating a reptilian mosaic that would have given the animal a knobby, textured appearance. Particularly noteworthy were the larger scales along the vertebral column, which formed small ridges or protuberances that may have served a display function or provided some minimal protection. This exceptional preservation allows paleontologists to reconstruct Carnotaurus with greater accuracy than most other dinosaurs from this period.

Size and Physical Dimensions

Carnotaurus was a medium-sized theropod dinosaur by Late Cretaceous standards, though still an imposing predator in its ecosystem. The holotype specimen measured approximately 7.5 to 8 meters (24.6 to 26.2 feet) in length from snout to tail tip, standing about 2.5 to 3 meters (8.2 to 9.8 feet) tall at the hip. Weight estimates for Carnotaurus generally range between 1.5 and 2.1 metric tons (1.7 to 2.3 short tons), making it considerably lighter than contemporaries like Tyrannosaurus rex but heavier than many other abelisaurids. Its body was characterized by a deep chest, powerful hind limbs, and a long, muscular tail that comprised nearly half of its total length. The neck was relatively short and strong, supporting the large, distinctive head. Interestingly, the specimen discovered is believed to be an adult, but not a fully mature individual, suggesting that some Carnotaurus individuals may have grown somewhat larger. The proportions of Carnotaurus reflect its specialized lifestyle as an active predator, with a body built for both strength and agility.

Hunting and Dietary Habits

As a dedicated carnivore, Carnotaurus likely occupied the niche of an active predator within its ecosystem, though its exact hunting strategies remain a subject of scientific debate. The combination of speed, powerful legs, and a specialized skull suggests that Carnotaurus employed a hunting style different from many other large theropods. Rather than the bone-crushing bite of tyrannosaurids, the relatively weak jaw musculature and blade-like teeth of Carnotaurus indicate it likely delivered slashing bites to weaken prey through blood loss. Some paleontologists hypothesize that it may have used its horns and reinforced skull for ramming attacks against prey or rivals, potentially stunning smaller animals before delivering fatal bites. The primary prey of Carnotaurus would have included the diverse herbivorous dinosaurs that shared its habitat, particularly the numerous titanosaur sauropods and smaller ornithopods that populated Late Cretaceous Argentina. Juvenile sauropods, which lacked the formidable size of adults, may have been particularly targeted by this agile predator.

Paleoenvironment and Ecosystem

During the Late Cretaceous period, when Carnotaurus lived, approximately 71 million years ago, the region that would become Argentina experienced a considerably different climate and geography than today. The La Colonia Formation, where the Carnotaurus holotype was discovered, represents what was once a coastal floodplain environment with seasonal streams and rivers flowing toward the nearby Atlantic Ocean. The climate was warmer and more humid than modern Patagonia, supporting a diverse ecosystem of plants and animals. Coniferous forests and fern prairies dominated the landscape, providing habitat for numerous herbivorous dinosaurs, including titanosaur sauropods like Aeolosaurus and Saltasaurus, which would have been the largest animals in the ecosystem. Other potential contemporaries included smaller herbivores such as the ornithopod Gasparinisaura, various mammals, crocodilians, turtles, and a variety of birds. As a top predator, Carnotaurus would have competed with other abelisaurid theropods for resources, occupying a crucial position in the food web of this ancient South American ecosystem.

Evolutionary Significance

Carnotaurus represents an evolutionary pinnacle of the abelisaurid lineage, showcasing the remarkable adaptations that occurred during the isolation of the southern continents. After the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana, South America became increasingly isolated, allowing its dinosaur fauna to evolve along distinctive paths separate from those in North America and Asia. The extreme specializations seen in Carnotaurus—its bizarre horns, extraordinarily reduced arms, and adaptations for speed—illustrate the principle of allopatric speciation, where geographic isolation leads to unique evolutionary trajectories. Particularly interesting is how abelisaurids like Carnotaurus evolved to fill the large predator niche in South America while tyrannosaurids dominated similar ecological roles in North America and Asia during the same period. Despite their different ancestries, both groups independently evolved reduced forelimbs, demonstrating convergent evolution in response to similar selective pressures. Carnotaurus thus provides paleontologists with valuable insights into how isolation shapes evolutionary processes and how predatory adaptations can develop along different pathways to solve similar ecological challenges.

Possible Social Behavior

While direct evidence of social behavior in Carnotaurus remains limited, the distinctive horns and other cranial features have led paleontologists to speculate about potential social dynamics within the species. The prominent horns may have served as display structures used in competition for mates or territory, similar to how modern horned mammals utilize their headgear. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the horns appear somewhat too delicate for regular use in hunting large prey. Some researchers suggest that Carnotaurus may have engaged in ritualized head-pushing contests, with males competing for dominance without causing serious injury to opponents. The extensive skin impressions preserved with the Carnotaurus specimen reveal no evidence of bright color patterns that might indicate complex visual displays, but this doesn’t preclude the possibility of seasonal color changes or behavioral displays using the distinctive horned profile. If Carnotaurus did engage in social behaviors, it likely involved visual signals, possibly including head movements that emphasized the unusual skull shape and horns.

Comparison to Other Theropods

When compared to other large theropod dinosaurs, Carnotaurus stands out for several anatomical peculiarities that distinguish it from both its relatives and unrelated predators from other continents. Unlike the heavy, bone-crushing skulls of tyrannosaurids, Carnotaurus possessed a lighter, shorter skull adapted for quicker, slashing bites. Its horns find no close parallel among other major theropod groups, representing a unique evolutionary development within Abelisauridae. While both Carnotaurus and Tyrannosaurus rex famously had reduced forelimbs, the arm reduction in Carnotaurus was even more extreme, with proportionally smaller limbs that were essentially non-functional. In terms of locomotion, Carnotaurus appears to have been built for greater speed than many large theropods, with leg proportions more similar to those of smaller, cursorial dinosaurs than to other apex predators of similar size. Within its own family, Abelisauridae, Carnotaurus represents an extreme form, with relatives like Majungasaurus from Madagascar and Abelisaurus (also from Argentina) showing less pronounced cranial ornamentation and different proportions, highlighting the diversity that evolved within this successful family of Southern Hemisphere predators.

Cultural Impact and Representation

Since its discovery in the 1980s, Carnotaurus has secured a distinctive place in popular culture, largely due to its unique appearance with bull-like horns and extraordinarily tiny arms. This charismatic theropod rose to prominence in Michael Crichton’s 1995 novel “The Lost World,” where it was portrayed as having chameleonic abilities—a fictional trait not supported by paleontological evidence, but which captured public imagination. Carnotaurus has subsequently appeared in numerous dinosaur documentaries, including the BBC’s “Walking with Dinosaurs: Ballad of Big Al” special, where its speed and predatory nature were highlighted. In the realm of film, Carnotaurus featured prominently in Disney’s 2000 animated feature “Dinosaur” as the primary antagonist, though depicted larger than its actual size for dramatic effect. More recently, it appeared in the “Jurassic World” franchise, further cementing its status in dinosaur popular culture. Museum exhibitions worldwide frequently feature Carnotaurus reconstructions, with its distinctive silhouette making it immediately recognizable to dinosaur enthusiasts, young and old, helping to bring attention to the unique dinosaur fauna that evolved in South America.

Ongoing Research and Recent Discoveries

Paleontological understanding of Carnotaurus continues to evolve as new analytical techniques are applied to existing specimens and comparative studies with newly discovered abelisaurids provide broader context. Recent biomechanical studies have used computer modeling to test hypotheses about Carnotaurus’s locomotion capabilities, with some research suggesting its unusual body proportions may have allowed for even greater speed than previously estimated. Advanced CT scanning of the skull has provided new insights into the brain structure and sensory capabilities of Carnotaurus, indicating well-developed optical lobes that suggest vision was an important sense for this predator. Detailed analysis of the preserved skin impressions using scanning electron microscopy has revealed microstructures not visible in earlier examinations, helping scientists better understand the integumentary covering of these animals. While additional complete Carnotaurus specimens remain elusive, fragmentary remains attributed to this genus or closely related forms have been reported from other formations in Argentina, potentially expanding our understanding of its geographic and temporal range. As research techniques continue to advance, this iconic dinosaur will undoubtedly reveal more secrets about its biology and evolutionary history.

Conclusion

Carnotaurus sastrei stands as a testament to the remarkable diversity of theropod dinosaurs that evolved during the Mesozoic Era. With its bizarre combination of bull-like horns, vestigial arms, and adaptations for speed, this distinctive predator represents a unique evolutionary experiment that thrived in the isolated ecosystems of Late Cretaceous South America. The exceptional preservation of the holotype specimen, complete with extensive skin impressions, has provided paleontologists with an unprecedented window into the life appearance of this fascinating dinosaur. As research continues and our understanding of abelisaurid evolution deepens, Carnotaurus will remain an iconic symbol of the strange and wonderful adaptations that arise through the processes of natural selection and geographic isolation. From its discovery in the windswept plains of Patagonia to its prominent place in museum displays and popular media worldwide, the “meat-eating bull” continues to captivate scientists and the public alike, reminding us of Earth’s remarkable prehistoric past.