In the twilight of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 76-70 million years ago, a distinctive horned dinosaur roamed the lush floodplains of what would become Alberta, Canada. Chasmosaurus, whose name means “opening lizard,” referring to the large openings in its elaborate neck frill, was a remarkable ceratopsian that has fascinated paleontologists since its discovery in the early 20th century. These plant-eating behemoths, with their distinctive three-horned faces and massive shield-like frills, have provided crucial insights into dinosaur evolution, behavior, and the prehistoric ecosystems of Late Cretaceous North America. As we explore the world of Chasmosaurus, we’ll uncover how these magnificent creatures lived, what made them unique among their ceratopsian relatives, and how their fossilized remains continue to enlighten our understanding of Earth’s distant past.

Discovery and Scientific Classification

Chasmosaurus was first scientifically described in 1914 by paleontologist Lawrence Lambe, who discovered specimens in the Dinosaur Provincial Park formation of Alberta, Canada. This remarkable dinosaur belongs to the family Ceratopsidae and specifically to the subfamily Chasmosaurinae, which includes other frilled dinosaurs like Triceratops and Torosaurus. The genus currently includes two well-established species: Chasmosaurus belli and Chasmosaurus russelli, which differ slightly in their frill morphology and horn arrangements. A third potential species, C. irvinensis, was later reclassified as a separate genus called Vagaceratops. Since its initial discovery, numerous Chasmosaurus specimens have been unearthed from the Dinosaur Park Formation, making it one of the better-understood ceratopsians with a relatively complete fossil record that includes partial skeletons, skulls, and even rare skin impressions.

Physical Characteristics and Size

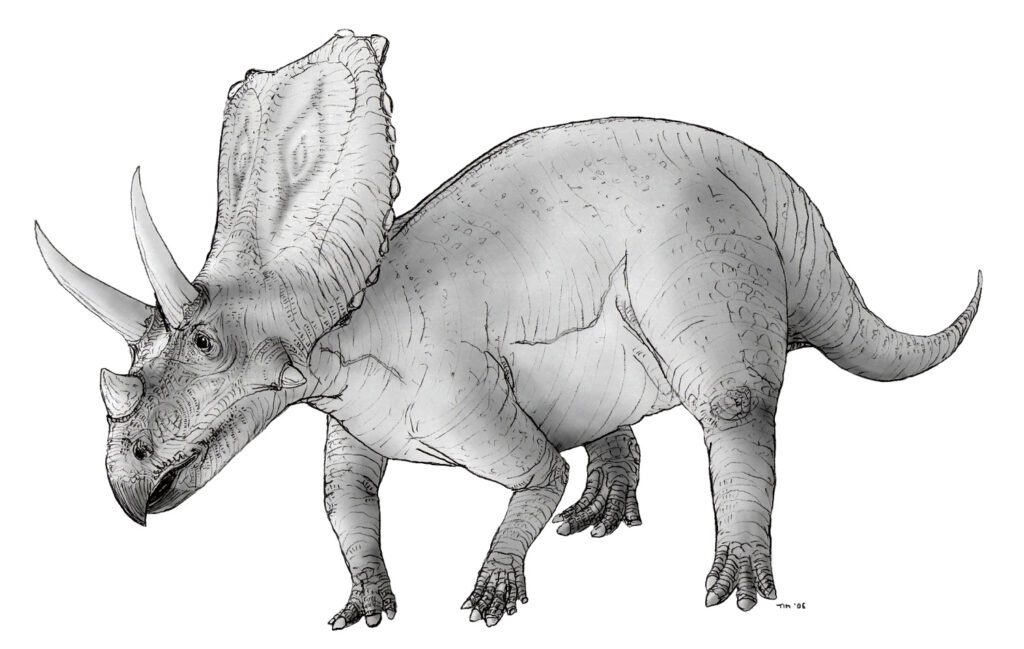

Chasmosaurus was a substantial quadruped, measuring approximately 5 meters (16 feet) in length and weighing around 2 tons when fully grown. Its most striking feature was undoubtedly its enormous heart-shaped frill, which extended from the back of the skull and could reach up to 1 meter (3 feet) across. Unlike some other ceratopsians, Chasmosaurus had a relatively flat frill with two large openings or “fenestrae” on either side, which likely served to reduce weight while maintaining structural integrity. The dinosaur possessed a robust beak-like mouth adapted for cropping vegetation, complemented by a series of shearing teeth arranged in dental batteries for efficient processing of tough plant material. Chasmosaurus featured a single horn on its nose and two longer horns above its eyes, though these were not as dramatic as those seen in its relative Triceratops. The animal’s body was barrel-shaped with sturdy limbs, providing the necessary support for its considerable bulk and massive head.

The Distinctive Frill: Form and Function

The elaborate frill of Chasmosaurus represents one of paleontology’s most intriguing evolutionary developments, with scientists proposing several theories about its purpose. The most compelling explanation suggests that the frill served multiple functions simultaneously. As a display structure, the frill likely played a crucial role in species recognition and sexual selection, with potential variations between males and females (sexual dimorphism). Some researchers have proposed that blood vessels running through the frill could have helped regulate body temperature through a process similar to how modern elephants use their ears. The frill may have also protected the neck region against predators, though the large fenestrae would have limited this defensive capability. Recent studies examining the growth patterns in Chasmosaurus frills indicate that they changed significantly throughout the animal’s life, suggesting the frill had important social signaling functions within herds and during courtship rituals.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Chasmosaurus inhabited what is now southern Alberta, Canada, particularly the area preserved in Dinosaur Provincial Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site renowned for its extraordinary fossil wealth. During the Late Cretaceous period, when Chasmosaurus thrived, this region looked dramatically different from today’s arid badlands. It was a lush, subtropical coastal plain intersected by numerous rivers that flowed eastward into the Western Interior Seaway, a vast inland sea that divided North America. The climate was warm and humid, supporting diverse forests of conifers, cycads, and early flowering plants that provided abundant food for herbivorous dinosaurs. This rich ecosystem supported a remarkable diversity of dinosaur species, with Chasmosaurus sharing its environment with other ceratopsians, hadrosaurs, ankylosaurs, and various predatory theropods. The geographic range of Chasmosaurus appears relatively limited compared to some other dinosaur genera, suggesting it may have been adapted to specific environmental conditions found in this particular region.

Diet and Feeding Adaptations

Chasmosaurus was a dedicated herbivore with specialized adaptations for processing the fibrous plant matter that constituted its diet. Its powerful beak-like structure at the front of the mouth worked like shears to crop vegetation, while batteries of closely packed teeth further back in the jaws efficiently processed tough plant materials. Unlike some herbivorous dinosaurs that swallowed vegetation whole for processing in gizzard-like stomachs, ceratopsians like Chasmosaurus performed significant oral processing with their advanced dental arrangements. The diet likely consisted primarily of cycads, ferns, and early flowering plants that were becoming increasingly common during the Late Cretaceous. Based on the height of Chasmosaurus at the shoulder, paleontologists believe it would have focused on low-growing vegetation rather than browsing from tall trees. The specialized dental adaptations, including continuous replacement of worn teeth throughout its lifetime, allowed Chasmosaurus to effectively utilize abundant but tough plant resources that other herbivores might have found difficult to digest.

Social Behavior and Herd Structure

Evidence from bone beds containing multiple Chasmosaurus individuals strongly suggests these dinosaurs lived in social groups or herds, similar to many modern herbivores. This gregarious behavior would have provided numerous advantages, including enhanced protection against predators and more efficient foraging strategies. The elaborate frills may have played important roles in social communication, potentially displaying different colors or patterns that signaled age, sex, or reproductive status within the herd. Some paleontologists hypothesize that Chasmosaurus herds might have had complex social hierarchies, with dominant individuals identified by the size or distinct features of their frills. Fossil evidence indicates that juveniles remained with adult groups, suggesting extended parental care and potentially complex family structures. The discovery of multiple growth stages of Chasmosaurus in certain bone beds suggests that herds included individuals of various ages, further supporting the theory of stable social groups rather than temporary aggregations.

Reproduction and Growth

Our understanding of Chasmosaurus reproduction has been dramatically enhanced by the remarkable discovery of a nearly complete juvenile specimen nicknamed “Baby Chasmosaurus,” found in Dinosaur Provincial Park in 2010. This exceptional fossil, representing an individual that died at approximately three years of age, provides crucial insights into how these dinosaurs developed. Like other dinosaurs, Chasmosaurus reproduced by laying eggs, likely in carefully constructed ground nests where the eggs could be protected from predators and environmental conditions. Based on what we know about related ceratopsians, clutch sizes were probably substantial, containing perhaps 20-30 eggs per nest. Growth studies examining bone histology reveal that Chasmosaurus likely experienced rapid growth in its early years, gradually slowing as it approached adult size. The frill and horn development occurred progressively throughout maturation, with juveniles having proportionally smaller and less elaborate frills than adults, suggesting these structures became increasingly important as individuals reached breeding age.

Predators and Defense Mechanisms

Despite its imposing size and armament, Chasmosaurus faced significant predatory threats in its Late Cretaceous environment. Chief among these predators was Gorgosaurus, a tyrannosaurid dinosaur that coexisted with Chasmosaurus in the Dinosaur Park ecosystem. Other potential threats included Daspletosaurus and various smaller dromaeosaurid predators. To counter these dangers, Chasmosaurus possessed several defensive adaptations beyond its sheer size. The facial horns provided obvious weapons against attackers, while the large frill, despite its fenestrae, offered some protection for the vulnerable neck region. The gregarious nature of Chasmosaurus provided the considerable advantage of safety in numbers, with herds likely positioning vulnerable juveniles in protected central positions when threatened. Some paleontologists speculate that when threatened, adult Chasmosaurus might have formed defensive circles around their young, presenting a formidable barrier of horns to approaching predators—a behavior observed in modern musk oxen facing wolf packs.

Extinction and Legacy

Chasmosaurus disappeared from the fossil record approximately 70 million years ago, roughly 5 million years before the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event that claimed all non-avian dinosaurs. This timing suggests that the genus was already in decline due to environmental changes or competition from other ceratopsians, rather than being directly eliminated by the asteroid impact. The ecological niche once occupied by Chasmosaurus was subsequently filled by other ceratopsids like Triceratops, which became dominant in the very latest Cretaceous ecosystems. The evolutionary innovations seen in Chasmosaurus, particularly its elaborate frill structure, represent important adaptations that influenced subsequent ceratopsid evolution. Today, Chasmosaurus continues to capture public imagination through museum displays, scientific research, and media representations, serving as an ambassador for the diverse ceratopsian family and the remarkable evolutionary adaptations of dinosaurs. Its fossils remain among the most impressive specimens in major natural history museums worldwide, including the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, which houses several exceptional Chasmosaurus specimens.

Paleoecology: Life in the Late Cretaceous

Chasmosaurus inhabited a complex and diverse ecosystem during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, approximately 76-70 million years ago. The Dinosaur Park Formation, where its fossils are predominantly found, represents an ancient coastal plain environment with a subtropical climate and seasonal rainfall patterns. This rich ecosystem supported a remarkable diversity of plant life, including horsetails, ferns, conifers, and early flowering plants, creating abundant food resources for herbivores. Chasmosaurus shared this environment with numerous other dinosaur species, including hadrosaurs like Corythosaurus and Lambeosaurus, the armored Euoplocephalus, other ceratopsians such as Centrosaurus, and various small theropods. Extensive fossil evidence from this formation suggests these diverse dinosaur communities were relatively stable for millions of years before changing environmental conditions led to faunal turnover. The relatively complete fossil record from this period allows paleontologists to reconstruct detailed food webs and ecological relationships, positioning Chasmosaurus as an important large-bodied primary consumer in this ancient ecosystem.

Fossil Discoveries and Notable Specimens

Since Lawrence Lambe’s original description in 1914, numerous significant Chasmosaurus specimens have been recovered from the Dinosaur Park Formation, collectively enhancing our understanding of this genus. Among the most scientifically valuable is a specimen discovered in 1936 by Charles M. Sternberg, which included a nearly complete skeleton with an exceptionally preserved skull showing remarkable frill details. In 2010, the discovery of a juvenile Chasmosaurus skeleton by paleontologist Philip Currie and his team provided unprecedented insights into the growth and development of these animals. This specimen, estimated to be just three years old at death, preserved approximately 75% of the skeleton, including portions rarely found in ceratopsian fossils. A particularly intriguing discovery in 2013 included fossilized skin impressions, revealing details of the scaly integument that covered parts of the Chasmosaurus’s body. The Royal Tyrrell Museum’s specimen known as “Skull 2280” represents one of the most complete and well-preserved Chasmosaurus skulls ever found, displaying the characteristic heart-shaped frill in exquisite detail and serving as a primary reference specimen for understanding the cranial anatomy of this genus.

Research and Scientific Importance

Chasmosaurus continues to hold significant scientific importance in paleontological research, contributing to our understanding of numerous aspects of dinosaur biology and evolution. The genus serves as a crucial reference point for understanding ceratopsid evolution, with its distinctive frill morphology representing an important intermediate stage between more primitive and more derived forms. Histological studies of Chasmosaurus bones have provided valuable data on growth rates and life history patterns in ceratopsians, while detailed analyses of skull morphology have helped clarify taxonomic relationships within the Chasmosaurinae subfamily. Recent research using advanced imaging techniques has revealed previously unknown details about brain structure and sensory capabilities in these animals. The relatively abundant fossil material from multiple individuals of different ages enables researchers to study population-level variations and ontogenetic changes. Additionally, isotopic analyses of Chasmosaurus teeth and bones have yielded insights into dietary preferences and seasonal migration patterns, while taphonomic studies of bone beds contribute to our understanding of paleoenvironmental conditions and preservation processes in the Late Cretaceous.

Chasmosaurus in Popular Culture

While not achieving the same level of popular recognition as its relative Triceratops, Chasmosaurus has nonetheless made notable appearances in paleontologically-oriented media and educational materials. The distinctive heart-shaped frill makes it visually recognizable and has secured its place in numerous dinosaur encyclopedias, museum exhibits, and educational programs focused on Cretaceous life. Chasmosaurus has appeared in several documentary series, including episodes othe f BBC’s “Walking with Dinosaurs” and various PBS NOVA specials on ceratopsian dinosaurs. The genus features in popular dinosaur-themed video games like “Jurassic World Evolution,” where players can create and manage populations of prehistoric creatures, including accurately rendered Chasmosaurus models. Children’s books frequently include Chasmosaurus when illustrating the diversity of horned dinosaurs, often highlighting its unique frill shape compared to the more familiar Triceratops. The Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta, showcases impressive Chasmosaurus specimens and interactive exhibits explaining the significance of these dinosaurs in the ancient ecosystems of what is now western Canada, helping to educate thousands of visitors annually about this fascinating genus.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Chasmosaurus

As we reflect on Chasmosaurus, we gain appreciation for a remarkable evolutionary experiment – a horned dinosaur whose distinctive frill and social nature helped it thrive in the ancient landscapes of Late Cretaceous Canada. Though separated from us by 70 million years, these magnificent creatures continue to captivate our imagination and expand our knowledge of Earth’s prehistoric past. Through ongoing discoveries and advancing research techniques, Chasmosaurus specimens preserved in the Canadian badlands continue to yield new insights into dinosaur biology, behavior, and evolution. The story of these frill-faced herbivores reminds us that the fossil record is not merely a collection of static relics, but a dynamic window into lost worlds and evolutionary processes that shaped life on our planet. As paleontologists continue their meticulous work in Dinosaur Provincial Park and similar fossil-rich environments, our understanding of Chasmosaurus and its place in the tapestry of prehistoric life will only grow richer and more detailed.