Confuciusornis, whose name translates to “Confucius bird,” represents one of the most significant discoveries in avian paleontology. Dating back approximately 125-120 million years to the Early Cretaceous period, this remarkable creature provides a crucial evolutionary link between dinosaurs and modern birds. As one of the earliest birds to possess a toothless beak similar to contemporary avian species, Confuciusornis offers paleontologists an exceptional window into the development of flight and avian characteristics. The abundance of well-preserved fossils found primarily in the Liaoning Province of northeastern China has allowed scientists to study this species in remarkable detail, making it one of the best-understood prehistoric birds and a cornerstone in our understanding of avian evolution.

Discovery and Naming of Confuciusornis

The first Confuciusornis fossils were discovered in the early 1990s in the famous Jehol Biota of northeastern China, particularly in the Yixian and Jiufotang Formations of Liaoning Province. The genus was officially named and described in 1995 by Chinese paleontologists, with the type species being Confuciusornis sanctus. The name “Confuciusornis” combines the name of the Chinese philosopher Confucius with the Greek word “ornis” meaning bird, honoring both its Chinese origin and avian nature. Since its initial discovery, hundreds of specimens have been unearthed, making Confuciusornis one of the most numerously preserved Mesozoic birds. This abundance of fossils, many with exceptional preservation including soft tissues and feathers, has provided scientists with unprecedented insights into early bird evolution that would be impossible with more fragmentary remains.

Geological Age and Habitat

Confuciusornis lived during the Early Cretaceous period, approximately 125-120 million years ago, in what is now northeastern China. During this time, the region was characterized by a warm temperate climate with numerous lakes and forests. The Jehol Biota, where Confuciusornis fossils are found, preserves an incredible ecosystem of diverse plants, invertebrates, fish, amphibians, reptiles, dinosaurs, mammals, and birds that lived alongside Confuciusornis. The exceptional preservation of these fossils is largely due to periodic volcanic eruptions that killed and rapidly buried organisms in fine ash, preventing decomposition and allowing for the preservation of delicate structures like feathers. The lake environment likely provided Confuciusornis with ample food resources, while the surrounding forests offered nesting sites and protection from larger predators, creating an ecological niche that allowed these early birds to thrive.

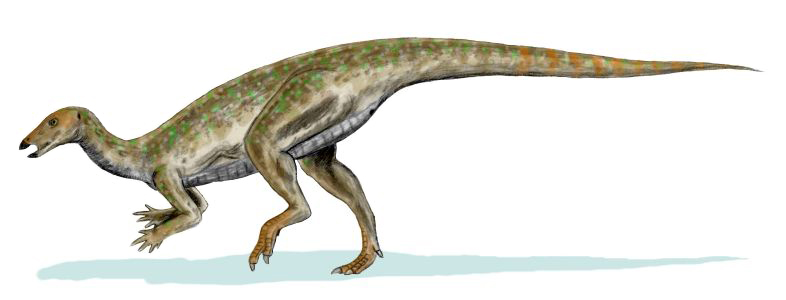

Physical Characteristics and Size

Confuciusornis was roughly the size of a modern crow, with adults measuring approximately 50-60 centimeters (20-24 inches) in length, though this includes their long tail feathers. Their body size was more comparable to that of a pigeon. Unlike most other Mesozoic birds, Confuciusornis possessed a completely toothless beak, remarkably similar to modern birds—a feature that represents one of its most evolutionarily advanced characteristics. The skull was relatively short with large eye sockets, suggesting good vision that would have been essential for flight and hunting. The wings of Confuciusornis were well-developed with three clawed digits, and the shoulder girdle showed adaptations for powered flight, though not as advanced as in modern birds. One of the most distinctive features was the presence of two extremely long, ribbon-like tail feathers in some specimens, believed to represent male individuals, suggesting sexual dimorphism similar to that seen in many modern bird species.

Evolutionary Significance

Confuciusornis occupies a pivotal position in the evolutionary history of birds, representing an important transitional form between earlier avialans like Archaeopteryx and modern birds (Neornithes). While Archaeopteryx still retained many dinosaurian features such as teeth and a long bony tail, Confuciusornis had already evolved several characteristics that define modern birds, most notably its toothless beak. This innovation was a significant evolutionary step, as it provided a lightweight alternative to heavy, tooth-bearing jaws. Despite these advanced features, Confuciusornis still retained several primitive characteristics, including clawed fingers on its wings and a skeletal structure not fully adapted for the efficient flight seen in modern birds. The mosaic of ancestral and derived traits in Confuciusornis provides crucial evidence for the step-by-step evolution of avian features and helps paleontologists understand the sequence in which modern bird characteristics emerged during the Mesozoic Era.

Feathers and Flight Capabilities

The exceptionally preserved fossils of Confuciusornis reveal sophisticated feather structures that provide valuable insights into early avian flight. These birds possessed pennaceous feathers (with a central shaft and barbs) on their wings and bodies, similar to modern flying birds. The wing feathers show an asymmetrical structure, a characteristic associated with flight capabilities in modern birds. Despite these adaptations, the flight apparatus of Confuciusornis was not as advanced as that of modern birds; it lacked a well-developed keel on the sternum for the attachment of strong flight muscles, and its shoulder joint was less mobile. These limitations suggest that while Confuciusornis was certainly capable of powered flight, it was probably not as agile or efficient in the air as modern birds. Some researchers propose that Confuciusornis may have employed a flight style similar to modern pheasants or partridges—capable of quick bursts of flight but not adapted for long-distance soaring or highly maneuverable flight.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

The toothless beak of Confuciusornis represents one of its most significant adaptations and provides important clues about its diet and feeding behavior. Unlike its toothed predecessors, Confuciusornis likely relied on its horny beak to capture and process food. The exact diet of Confuciusornis remains somewhat speculative, but analysis of its skeletal structure and beak shape suggests it was potentially omnivorous, feeding on a combination of seeds, fruits, insects, and possibly small vertebrates. Some specimens have been found with preserved stomach contents containing fish remains, indicating that at least some individuals included aquatic prey in their diet. The transition to a toothless beak marked a significant evolutionary innovation that allowed for specialized feeding strategies without the weight and development costs of teeth. This adaptation proved so successful that it has persisted in virtually all modern birds, allowing them to exploit diverse food sources with specialized beak shapes derived from this basic toothless structure.

Sexual Dimorphism and Reproduction

One of the most intriguing aspects of Confuciusornis is the evidence for sexual dimorphism—physical differences between males and females—that it provides. Some specimens exhibit a pair of extremely elongated tail feathers that could reach up to 20 centimeters in length, while others lack these elaborate structures. Paleontologists generally interpret the specimens with long tail feathers as males and those without them as females, similar to the ornamental feathers seen in many modern bird species used for courtship displays. This represents some of the earliest evidence of sexual selection in the avian evolutionary lineage. While no fossilized eggs or nests have been definitively attributed to Confuciusornis, its skeletal similarities to modern birds suggest it likely laid eggs and may have exhibited some form of parental care. The presence of sexual dimorphism also implies complex social behaviors and mating systems, further supporting the notion that many aspects of modern bird behavior had already evolved by the Early Cretaceous period.

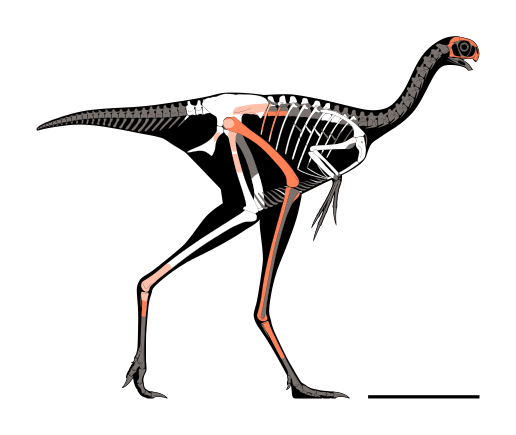

Skeletal Anatomy and Adaptations

The skeletal structure of Confuciusornis reveals a fascinating mixture of primitive and advanced features that illuminate its transitional position in avian evolution. Its skull was lightly built with a fused beak, lacking teeth entirely—a characteristic of modern birds. The vertebral column showed some fusion in the lower back, but not to the extent seen in modern birds. Confuciusornis possessed a pygostyle (a fused set of tail vertebrae), another modern bird characteristic that provides attachment points for tail feathers, though its pygostyle was longer than in modern birds. The shoulder girdle included a furcula (wishbone) and a somewhat expanded coracoid, adaptations associated with flight, though its sternum lacked the pronounced keel seen in modern flying birds. The forelimbs were modified into wings with three digits bearing claws, unlike modern birds which have reduced or hidden digit bones. The hindlimbs were bird-like but retained some primitive features in the ankle and foot structure, suggesting Confuciusornis was adapted for perching in trees but may have moved somewhat differently than modern birds when on the ground.

Ecological Role and Interactions

Within the rich ecosystem of the Jehol Biota, Confuciusornis likely occupied an ecological niche somewhat similar to modern perching birds. The lake-forest environment would have provided ample opportunities for these birds to feed, nest, and avoid predators. As potentially omnivorous creatures, they would have played important roles in seed dispersal and insect control. Fossils from the same formations reveal that Confuciusornis shared its habitat with various dinosaurs, including small dromaeosaurids that might have posed a predatory threat. Other avian contemporaries included the toothed bird Jeholornis and the more primitive Sapeornis, suggesting a diverse avian community was already developing. Interestingly, the abundance of Confuciusornis fossils—found by the hundreds—suggests they may have been living in flocks or colonies, similar to many modern bird species. This social behavior would have provided advantages in predator detection and possibly in foraging efficiency, allowing these early birds to thrive in an environment still dominated by dinosaurs.

Species Diversity

While Confuciusornis sanctus is the type species and by far the most common in the fossil record, paleontologists have identified several other species within the genus. These include Confuciusornis dui, which was somewhat larger than C. sanctus, and Confuciusornis feducciai, named after the renowned ornithologist Alan Feduccia. Each species shows slight variations in size, proportions, and anatomical details, suggesting that the Confuciusornis genus had already undergone some adaptive radiation during the Early Cretaceous. Beyond the Confuciusornis genus itself, closely related birds form the family Confuciusornithidae, including genera such as Changchengornis and Eoconfuciusornis, the latter being the oldest known member of the family dating to about 131 million years ago. This diversity indicates that the toothless beak adaptation was successful enough to support multiple species exploiting slightly different ecological niches within the same general environment, foreshadowing the incredible diversification that birds would undergo following the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous period.

Preservation Quality and Taphonomy

The exceptional preservation of Confuciusornis fossils provides a rare opportunity to study an ancient bird in remarkable detail. Many specimens include not just bones but also soft tissues, impressions of skin, and most importantly, feathers—structures that are rarely preserved in the fossil record. This extraordinary preservation is due to the unique depositional environment of the Jehol Biota, characterized by fine-grained lake sediments and volcanic ash that quickly buried the animals after death. The rapid burial prevented scavenging and minimized decomposition, while the fine sediments could capture impressions of delicate structures. Some specimens even show evidence of original organic compounds preserved within the fossils. Taphonomic studies (investigations of how organisms are preserved as fossils) indicate that many Confuciusornis individuals likely died during periodic catastrophic events such as volcanic eruptions or toxic algal blooms in the ancient lakes, explaining why so many specimens are found in discrete layers. This exceptional preservation has allowed scientists to study aspects of Confuciusornis biology that would otherwise remain unknown, making it one of the most important fossil birds for understanding avian evolution.

Research History and Significant Discoveries

Since its initial description in 1995, Confuciusornis has been the subject of extensive scientific research that has revolutionized our understanding of early bird evolution. Early studies focused primarily on describing the basic anatomy and taxonomic relationships of this unusual bird. As more specimens were discovered, researchers began investigating specific aspects of Confuciusornis biology, including its flight capabilities, growth patterns, and soft tissue anatomy. A landmark study in 2010 identified the presence of melanosomes (pigment-containing structures) in the fossilized feathers, allowing scientists to determine that some Confuciusornis individuals had patches of black and reddish-brown plumage. In 2018, researchers used advanced synchrotron techniques to identify chemical traces of original proteins in Confuciusornis fossils, providing new insights into molecular preservation in ancient specimens. Most recently, studies have employed sophisticated biomechanical analyses to better understand the flight capabilities of Confuciusornis, with some research suggesting it had a unique flight style distinct from both its dinosaurian ancestors and modern birds, representing an experimental stage in the evolution of avian flight.

Importance of Understanding Bird Evolution

Confuciusornis stands as one of the most significant fossil birds in our understanding of avian evolution, providing crucial insights into how modern bird characteristics emerged over time. Its toothless beak represents one of the earliest appearances of this defining avian feature, demonstrating that this adaptation evolved relatively early in bird evolution, long before many other modern bird characteristics. By comparing Confuciusornis with earlier forms like Archaeopteryx and later Cretaceous birds, paleontologists have been able to establish a clearer timeline for the acquisition of avian traits. The mixture of primitive features (clawed wings, certain skull characteristics) and derived features (toothless beak, pygostyle) in Confuciusornis demonstrates that bird evolution did not proceed in a simple, linear fashion but rather as a mosaic, with different characteristics evolving at different rates. Additionally, the sexual dimorphism evident in Confuciusornis suggests that complex social and reproductive behaviors typical of modern birds were already developing in the Early Cretaceous, providing a deeper time perspective on avian behavioral evolution that enriches our understanding of birds as a whole.

Conclusion

Confuciusornis represents a fascinating chapter in the story of bird evolution, providing a rare glimpse into the transition between dinosaurs and modern birds. With its toothless beak, well-developed feathers, and mixture of primitive and advanced features, this Early Cretaceous bird embodied an experimental stage in avian evolution when key adaptations were being tested. The exceptional preservation of hundreds of specimens has allowed scientists to study aspects of its biology ranging from skeletal anatomy and flight capabilities to plumage coloration and social behavior, making Confuciusornis one of the most comprehensively understood prehistoric birds. As research techniques continue to advance, these remarkable fossils will undoubtedly yield even more insights into the evolutionary journey that ultimately produced the diverse array of birds that inhabit our world today, connecting us to a distant past when the skies first became the domain of feathered flyers.