Picture this: you’re pedaling your bike down a forest path when suddenly, the ground starts shaking. Through the trees, you catch a glimpse of something massive moving toward you. Your heart races as you realize it’s a Tyrannosaurus Rex, the king of all predators, and it’s heading straight for you. You pump your legs harder, but can you actually outrun this prehistoric monster on two wheels?

The Raw Power Behind T-Rex Movement

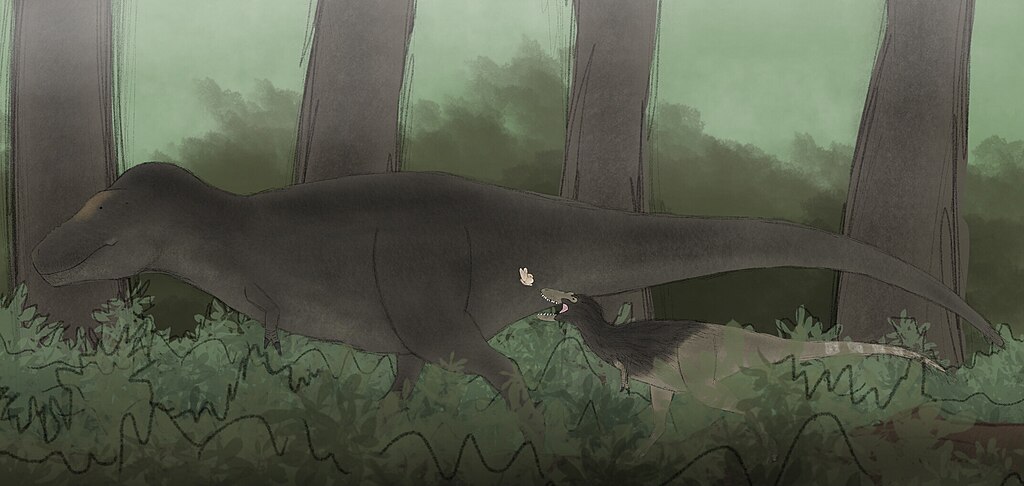

When we talk about T-Rex speed, we’re dealing with a creature that weighed between 8 to 14 tons and stood about 12 feet tall at the hips. That’s like having a fully loaded school bus chasing you, except this bus has teeth the size of bananas and a bite force that could crush a car.

The sheer mass of a T-Rex created both advantages and limitations for its mobility. While those massive leg muscles could generate tremendous power, they also had to support an enormous amount of weight with each stride.

Scientific Speed Estimates for Tyrannosaurus Rex

Modern paleontologists have used computer modeling and biomechanical analysis to estimate T-Rex running speeds. The most widely accepted research suggests these giants could reach speeds between 12 to 18 miles per hour during short bursts. Some more optimistic estimates push this up to 25 mph, though this remains hotly debated in scientific circles.

These calculations take into account bone density, muscle attachment points, and the physics of bipedal locomotion for such a massive animal. The numbers might seem modest compared to modern predators, but remember we’re talking about an animal that’s literally the size of a city bus.

How Fast Can a Human Bike Rider Actually Go

An average recreational cyclist can maintain speeds of 12 to 16 mph on flat terrain without breaking too much of a sweat. Experienced cyclists can easily cruise at 20 to 25 mph, while competitive riders can sustain 28 to 30 mph during races.

The key advantage here is that bicycles are incredibly efficient machines. They multiply human power through mechanical advantage, allowing us to move much faster than our legs alone could carry us. Plus, we don’t have to support 14 tons of body weight while doing it.

Terrain plays a huge role too. Downhill, even casual riders can hit 35 to 40 mph without pedaling hard, while uphill speeds might drop to 8 to 12 mph depending on the grade.

The Physics of Dinosaur Locomotion

Running at massive size presents unique challenges that smaller animals simply don’t face. As body size increases, the stress on bones and joints increases exponentially. A T-Rex moving at full speed would experience forces that could potentially shatter its own leg bones if it stumbled or landed wrong.

Scientists have calculated that the “safety factor” for T-Rex bones was relatively low compared to smaller dinosaurs. This suggests they were built more for power and intimidation than for sustained high-speed chases.

The biomechanics also show that T-Rex likely used a fast walk or trot rather than a full gallop. Their gait would have been more like a giant, terrifying power walk than the bounding run we see in movies.

Terrain Advantages for Modern Cyclists

Modern bicycles excel on paved roads, smooth trails, and even moderately rough terrain. A mountain bike can handle roots, rocks, and uneven ground that would slow down any large predator. Road bikes on smooth pavement can reach speeds that would make even a cheetah jealous.

The Cretaceous period landscape was quite different from today’s world. There were no paved roads, no smooth bike paths, just forests, swamps, and rocky terrain. This environment would favor the T-Rex’s powerful legs over a bicycle’s narrow wheels.

Endurance: The Marathon vs Sprint Factor

Here’s where things get really interesting. While a T-Rex might match or even exceed a cyclist’s speed in short bursts, endurance is a completely different game. Large predators are typically ambush hunters, not marathon runners.

A T-Rex would likely exhaust itself after a few minutes of high-speed pursuit. Its massive body would generate enormous amounts of heat, and its cardiovascular system would struggle to keep up with the oxygen demands. Meanwhile, a moderately fit cyclist could maintain 15 to 20 mph for hours.

Think of it like comparing a drag racer to a touring motorcycle. The drag racer might win in a straight line for a quarter mile, but the motorcycle will still be running long after the drag racer has overheated and broken down.

The Ambush Hunting Strategy

T-Rex wasn’t built for long chases anyway. Like most large predators, it was probably an ambush hunter that relied on surprise and overwhelming force rather than sustained pursuit. Modern big cats, bears, and crocodiles all use similar strategies.

The real danger wouldn’t be in a straight-up race across open ground. It would be in that first explosive burst when the T-Rex launches itself from hiding. Those first few seconds would be absolutely terrifying and potentially deadly.

Turning Radius and Maneuverability Comparison

A bicycle’s greatest advantage might not be top speed, but agility. Bikes can make sharp turns, navigate between obstacles, and change direction almost instantly. A 14-ton T-Rex would have the turning radius of a freight train.

Physics tells us that momentum equals mass times velocity. At T-Rex’s size, even moderate speeds would create enormous momentum that would be nearly impossible to redirect quickly. A smart cyclist could potentially escape by making sharp turns and weaving through obstacles.

This is similar to how small fish escape sharks or how motorcycles can outmaneuver cars in traffic. Size and power don’t always win against agility and intelligence.

Environmental Factors in Cretaceous Times

The world 66 million years ago was a very different place. CO2 levels were much higher, creating a greenhouse climate with no polar ice caps. Temperatures were warmer, and the landscape was dominated by ferns, conifers, and early flowering plants.

Oxygen levels were also different, which could affect both the T-Rex’s performance and a time-traveling cyclist’s endurance. The terrain would have been softer in many places, with more swampy areas that could bog down a bicycle but might not slow a T-Rex as much.

The Reality of Bone Stress and Injury Risk

Recent studies have shown that T-Rex fossils often display evidence of stress fractures and bone injuries, particularly in the legs. This suggests that even normal daily activities put enormous strain on their skeletal system.

Running at full speed would have been incredibly risky for a T-Rex. A single misstep could result in a catastrophic injury that would likely be fatal for such a large animal. This natural brake system would have limited how often and how hard they could push their maximum speed.

It’s like the difference between a Formula 1 car and a monster truck. The F1 car is faster, but it’s also much more fragile and can’t handle the same abuse.

Modern Bike Technology vs Prehistoric Predation

Today’s bicycles are marvels of engineering that would seem like magic to any creature from the Cretaceous period. Carbon fiber frames, precision gearing, and advanced tire compounds create machines that are both incredibly light and remarkably efficient.

A modern road bike weighs less than 20 pounds and can transfer over 95% of a rider’s energy into forward motion. Compare that to a biological system where much of the energy goes into supporting body weight, generating heat, and maintaining vital functions.

Electric bikes add another dimension entirely, allowing riders to maintain 20+ mph speeds with minimal effort and extending range dramatically.

Predator Behavior and Hunting Patterns

Understanding how modern large predators behave gives us insights into how T-Rex might have hunted. Lions, tigers, and bears typically rely on short, explosive attacks rather than extended chases. They conserve energy and only commit to high-speed pursuits when success seems likely.

A T-Rex would probably have given up the chase once it became clear the prey was maintaining distance. The energy cost of pursuing a fast-moving target would quickly outweigh the potential caloric gain from catching it.

This behavior is seen across the animal kingdom. Even cheetahs, the fastest land animals, will abandon a chase if they don’t catch their prey within a minute or two.

The Verdict: Who Wins the Race

In a straight-line sprint over short distances, a T-Rex might actually have a chance against a casual cyclist, especially on rough terrain. However, over any significant distance or on improved surfaces, the bicycle wins hands down.

The real-world scenario would likely play out like this: the T-Rex gets one explosive opportunity to catch its prey in the first few seconds. If that fails, the cyclist escapes easily through superior endurance and maneuverability.

Modern estimates suggest that on flat, paved ground, even a moderately fit cyclist could outrun a T-Rex within the first quarter mile and would be completely out of danger within the first mile.

What This Tells Us About Prehistoric Life

This thought experiment reveals something fascinating about how life worked in the age of dinosaurs. The largest predators weren’t necessarily the fastest, but they were the most powerful and intimidating. They controlled their environment through presence and overwhelming force rather than speed.

It also highlights how modern technology has changed the game entirely. Humans without tools would have been easy prey for a T-Rex, but with something as simple as a bicycle, we gain advantages that would have been impossible to imagine 66 million years ago.

The next time you’re out for a bike ride and feeling a bit sluggish, remember that you’re still moving faster than the most fearsome predator that ever walked the Earth. Your weekend cycling speed would have made you practically untouchable in the Cretaceous period. Makes you wonder what other prehistoric challenges modern technology could help us tackle, doesn’t it?