When we think of technological revolutions, we immediately picture humans developing steam engines, electricity, and eventually computers. But what if dinosaurs, given their 165-million-year reign on Earth, had the potential to develop their own version of advanced civilization? This thought experiment pushes us to reconsider our assumptions about intelligence, evolution, and the prerequisites for technological advancement. Dinosaurs dominated our planet for far longer than humans have existed, raising fascinating questions about alternative evolutionary paths that intelligence might have taken. While entirely speculative, examining this possibility reveals interesting insights about both dinosaur biology and the nature of technological development itself.

The Intelligence Question: Were Any Dinosaurs Smart Enough?

When assessing dinosaurs’ potential for developing technology, intelligence is the first crucial factor to consider. Troodontids and certain dromaeosaurids (raptor dinosaurs) possessed the highest encephalization quotients among dinosaurs, with brain-to-body ratios approaching those of some modern birds. Paleontologists have estimated that Troodon, with its relatively large brain and stereoscopic vision, might have had cognitive abilities comparable to those of modern ostriches or emus. However, even the smartest dinosaurs fell significantly short of the cognitive capabilities observed in corvids (ravens and crows), parrots, or primates—let alone humans. The neural architecture required for abstract thinking, complex problem-solving, and cultural transmission of knowledge appeared absent in even the most advanced dinosaur brains we’ve studied.

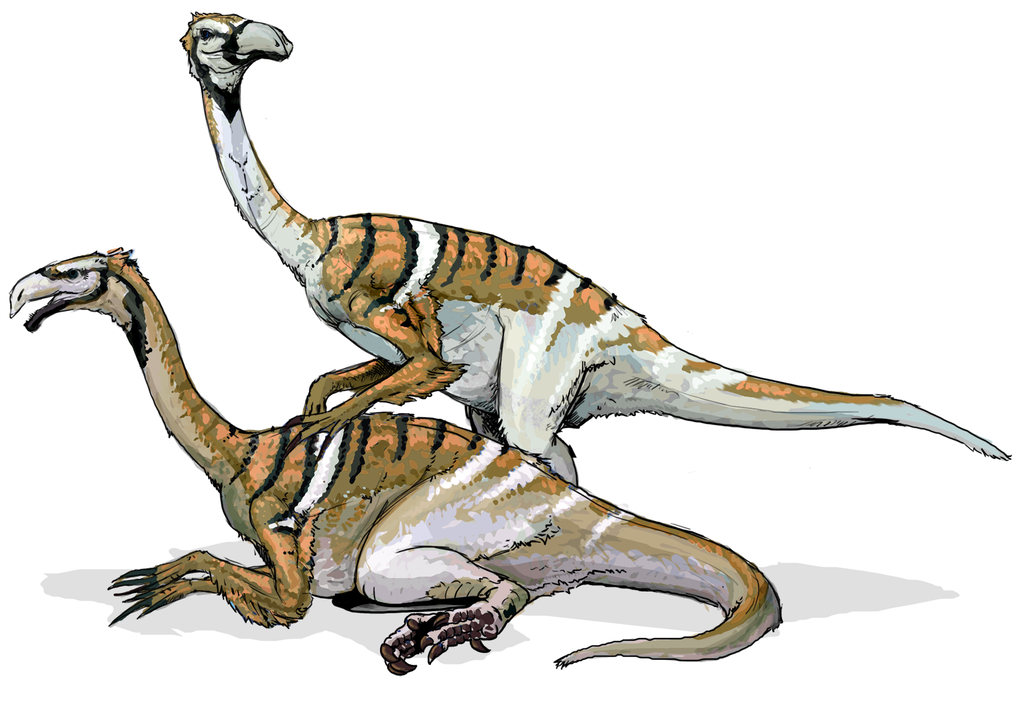

Manual Dexterity: The Hands That Build

Perhaps the most significant barrier to dinosaur technological development was the lack of manipulative appendages capable of precise movements. Theropod dinosaurs like Velociraptor had three-fingered hands that could grasp objects, but they lacked the thumb opposability that gives human hands their remarkable versatility. Without the ability to manipulate objects with precision, even a hypothetically intelligent dinosaur would struggle to craft complex tools. The physical constraints of dinosaur anatomy would have made tasks like knapping stone tools, weaving fibers, or constructing mechanical devices extraordinarily difficult. Most herbivorous dinosaurs faced even greater limitations, with limbs adapted primarily for locomotion rather than manipulation. This fundamental anatomical constraint would have presented a nearly insurmountable obstacle to technological development, regardless of cognitive capabilities.

Social Structures and Knowledge Transfer

Technological revolutions require not just individual intelligence but social structures that allow knowledge to accumulate and spread across generations. Evidence suggests some dinosaurs exhibited complex social behaviors—pack hunting in certain theropods, herding in many herbivores, and potential parental care in several lineages. Maiasaura, for instance, appears to have tended to its young in nest colonies. However, we have little evidence for the kind of multi-generational, sophisticated social structures needed to develop and maintain technological knowledge. Human technological advancement depends on cultural transmission mechanisms like language, writing, and formalized education. Without similar social systems for preserving and building upon discoveries, even occasional dinosaur “inventions” would likely have been lost rather than refined over generations into increasingly sophisticated technologies.

Environmental Pressures: The Mother of Invention

Necessity drives innovation, and dinosaurs faced plenty of environmental challenges during their long reign. The question is whether these pressures would have pushed toward technological solutions. For much of the Mesozoic Era, dinosaurs thrived in relatively stable, warm climates with abundant vegetation. These conditions might not have created the same pressures that drove human ancestors to develop tools and controlled fire as adaptations to changing environments. When dinosaurs did face catastrophic environmental changes, such as the end-Cretaceous extinction event, the timeframe was too compressed for evolutionary adaptation toward greater intelligence or technological development. Humans developed technology partly in response to survival challenges in variable environments—a situation many dinosaur lineages didn’t experience to the same degree during their evolutionary history.

Energy Requirements: Fueling an Industrial Revolution

Any industrial revolution requires concentrated energy sources to power machinery and manufacturing processes. Humans harnessed first wood, then coal, oil, and eventually nuclear energy to fuel technological advancement. Dinosaurs would have needed not only to discover such energy sources but also to develop means of extracting and utilizing them. The geological processes that created coal deposits were active during the Carboniferous period, before dinosaurs evolved, though new deposits formed throughout the Mesozoic. Oil deposits were similarly forming during dinosaur times. Theoretically, these energy sources existed in the dinosaur era, but the conceptual leap from recognizing combustible materials to harnessing them for mechanical energy would have required cognitive abilities far beyond what even the most intelligent dinosaurs likely possessed.

The Limitations of Biology vs. Technology

Dinosaurs evolved remarkable biological adaptations during their reign—massive size, defensive armor, deadly offensive weapons, efficient respiratory systems, and diverse feeding strategies. Their evolutionary success relied on biological solutions to environmental challenges rather than technological ones. When dinosaurs needed to regulate body temperature, they evolved feathers, not clothing or shelter-building behaviors. When they needed to process tough plant material, they developed specialized digestive systems rather than cooking techniques. This successful biological adaptation may have reduced selection pressure for cognitive traits that would lead to technological innovation. The evolutionary paths that lead to biological adaptation versus technological innovation represent fundamentally different strategies for survival and reproductive success.

Alternative Forms of “Technology”

Perhaps we should broaden our definition of technology beyond the human-centric view of mechanical devices and manufactured goods. Dinosaurs may have developed complex behavioral adaptations that served similar functions to primitive human technologies. Social hunting strategies in dromaeosaurids might have been as sophisticated as early human hunting techniques. Nesting behaviors and potential use of environmental materials for thermoregulation could be considered primitive environmental engineering. Some birds, the living descendants of dinosaurs, show remarkable tool use—crows fashion tools from twigs and New Caledonian crows even create compound tools. While not industrial in nature, these behaviors suggest that the dinosaur lineage did contain the potential for simple technological innovation, even if it manifested primarily after the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs.

The Timeline Problem: Evolutionary Pacing

Dinosaurs had an extraordinarily long evolutionary history, spanning approximately 165 million years from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous. By comparison, anatomically modern humans have existed for only about 300,000 years, with technological civilization emerging in just the last 10,000 years. Given enough time, could dinosaur intelligence have eventually evolved toward technology-creating capability? The question hinges on whether intelligence of the human type represents an inevitable evolutionary outcome given sufficient time. Evolutionary biologists generally reject the notion of predetermined evolutionary trajectories. The specific combination of selective pressures that led to human intelligence appears to have been unique rather than inevitable. Despite their long reign, dinosaurs showed no clear evolutionary trend toward increasingly sophisticated cognitive abilities that would eventually lead to technological capacity.

Avian Dinosaurs: The Success Story

While non-avian dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago, their descendants—birds—represent one of the most successful vertebrate groups on the planet today. Birds evolved from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs and inherited their ancestors’ relatively large brain-to-body ratios. Modern corvids, in particular, show remarkable problem-solving abilities, including tool use, recognition of human faces, and understanding of causal relationships. New Caledonian crows craft specialized tools from materials in their environment and even store them for future use. African grey parrots demonstrate language comprehension abilities comparable to young children. These cognitive capabilities suggest that the dinosaur lineage did indeed have the potential for significant intelligence, though it manifested most strongly in their avian descendants rather than in the non-avian dinosaurs themselves.

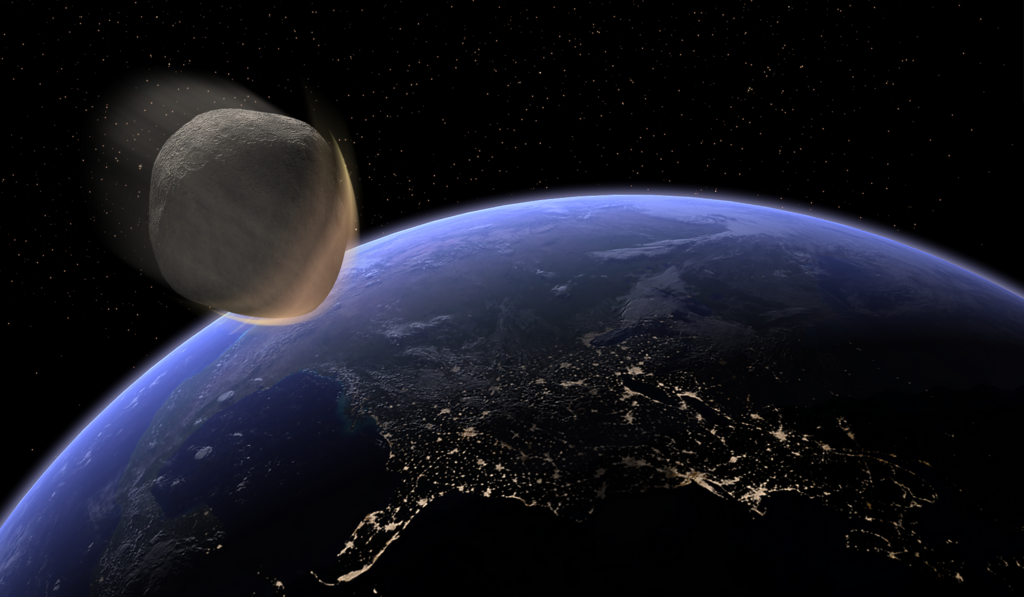

The Asteroid Impact: A Premature End?

The Chicxulub asteroid impact that triggered the end-Cretaceous mass extinction represents one of evolution’s great “what if” moments. This catastrophic event eliminated all non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago, cutting short any potential future evolutionary trajectories they might have followed. Some paleontologists have speculated about alternative histories where this extinction never occurred. Would continued dinosaur evolution eventually have produced species with human-like intelligence? The fossil record from the late Cretaceous shows no clear evidence that dinosaurs were evolving toward significantly greater intelligence before their extinction. Maniraptoran dinosaurs like Troodon had achieved relatively high encephalization quotients millions of years earlier, but this cognitive evolution appears to have plateaued rather than continuing toward human-like intelligence. The asteroid impact likely didn’t interrupt an inexorable march toward dinosaur civilization but rather reset Earth’s evolutionary stage.

Mammalian Competition: The Parallel Path

Throughout the Mesozoic Era, early mammals coexisted with dinosaurs, generally occupying nocturnal niches and smaller body size categories. These early mammals, despite their limitations, showed evolutionary trends toward increased brain size relative to body mass. Had dinosaurs begun developing primitive technology, they would have faced competition from increasingly intelligent mammals. After the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, mammals underwent an explosive adaptive radiation, eventually producing multiple lineages with high intelligence, including primates, cetaceans, and proboscideans. This mammalian pattern suggests that the ecological conditions of Earth may have increasingly favored the evolution of intelligence during the Cenozoic in ways they didn’t during the dinosaur-dominated Mesozoic. Perhaps the world of the dinosaurs simply wasn’t ready for the emergence of technological civilization, regardless of the dinosaurs’ own capabilities.

The Unique Path of Human Technology

Human technological development followed a specific evolutionary and cultural path that would be difficult to replicate. Our lineage evolved bipedalism first, freeing hands for tool use long before our brains significantly expanded. Early hominins used stone tools for millions of years before developing anything resembling complex technology. Language capabilities, another prerequisite for cumulative cultural evolution, evolved gradually over hundreds of thousands of years. Fire use, agriculture, metallurgy, and eventually industrialization all built upon previous innovations in a long chain of technological development. Each step required specific cognitive abilities, manual dexterity, and social structures that appear to have been uniquely human. The particular pathway that led to human technological civilization was highly contingent on specific evolutionary pressures and historical circumstances that differed markedly from those experienced by dinosaur lineages.

A Different Kind of Civilization?

Perhaps the most intriguing possibility is not that dinosaurs could have replicated human-style industrial civilization, but that they might have developed something entirely different. Intelligence can manifest in numerous ways beyond the human pattern of tool-making and environmental manipulation. Advanced dinosaur species might have evolved complex communication systems, social structures, or environmental interactions that wouldn’t leave obvious fossil traces. Certain modern animals show forms of culture and knowledge transmission that don’t rely on physical artifacts—dolphin hunting techniques passed between generations, or bird song dialects that vary between populations. A hypothetical advanced dinosaur civilization might have emphasized biological and behavioral adaptations rather than external technology, creating a type of complexity that wouldn’t register in our artifact-focused conception of civilization. Such alternative forms of complexity would be nearly impossible to detect in the fossil record.

Conclusion: The Improbable Dinosaur Engineers

While the notion of dinosaurs developing their own industrial revolution makes for fascinating speculation, the evidence suggests it was highly improbable. The combination of cognitive limitations, physical constraints on manipulation, and evolutionary pathways that favored biological rather than technological adaptation made dinosaur technology an evolutionary road not taken. Yet this thought experiment offers valuable insights into the contingent nature of technological development and the diversity of possible intelligent adaptations. The dinosaur lineage did eventually produce remarkable intelligence in the form of corvids and parrots, suggesting that the seeds of cognitive complexity were present all along. Perhaps the most appropriate conclusion is not that dinosaurs failed to achieve technology, but that they succeeded spectacularly through entirely different evolutionary strategies—dominating Earth for 165 million years through biological innovation rather than technological invention. Their success reminds us that technology represents just one possible solution to the challenges of survival in a complex and changing world.