When we sit down to enjoy our favorite foods, our taste buds allow us to experience a symphony of flavors – the sweetness of chocolate, the sourness of lemons, or the spicy kick of chili peppers. But have you ever wondered about the sensory experiences of creatures that roamed Earth millions of years ago? Dinosaurs dominated our planet for over 165 million years, yet their ability to taste remains shrouded in mystery. Recent scientific advances in paleontology, comparative anatomy, and genetic studies have begun to shed light on this fascinating question. By examining fossil evidence, studying the taste receptors of modern dinosaur descendants like birds, and analyzing evolutionary biology, scientists can now make educated hypotheses about dinosaur taste perception. Let’s explore what dinosaurs might have tasted, why taste mattered to these ancient creatures, and how their sensory experiences compared to our own.

The Evolutionary Purpose of Taste

Taste serves a critical evolutionary function across all species – it helps animals identify nutritious foods and avoid potential toxins. For dinosaurs, as with modern animals, taste receptors would have played a crucial role in survival. The ability to detect bitterness likely warned dinosaurs away from poisonous plants, while sweetness detection could have guided them toward energy-rich, carbohydrate-dense food sources. Taste sensitivity would have been particularly important for herbivorous dinosaurs like Triceratops or Brachiosaurus, who needed to distinguish between safe and harmful vegetation. Carnivorous dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex likely relied more on smell than taste for hunting, but taste would still have helped them avoid consuming spoiled meat. This fundamental connection between taste and survival suggests that dinosaurs almost certainly possessed some form of taste perception, even if it differed from mammals.

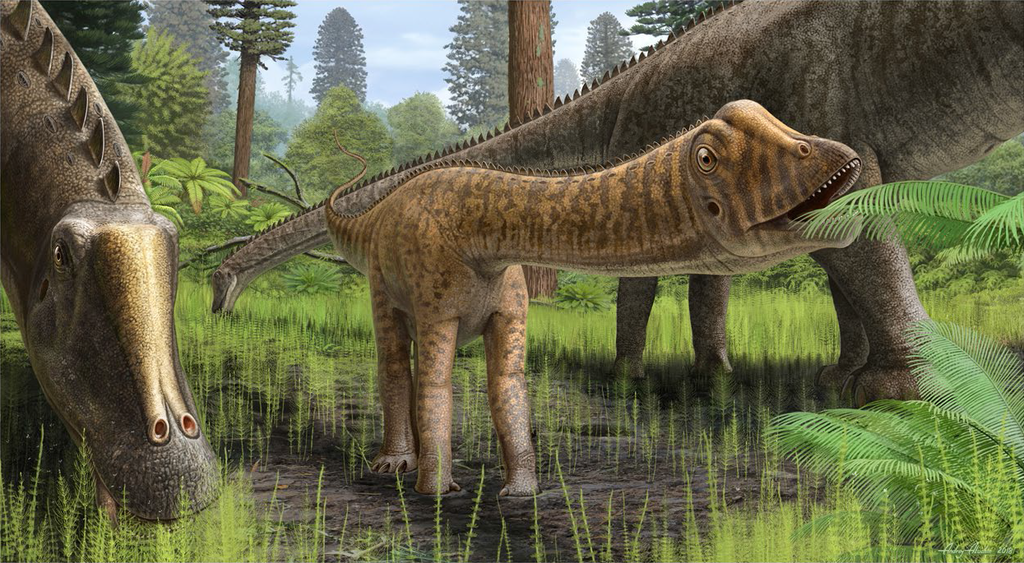

What Dinosaur Taste Buds Might Have Looked Like

While soft tissues like taste buds rarely fossilize, scientists can make educated guesses about dinosaur taste receptors based on their closest living relatives. Birds and crocodilians, both descendants of the archosaur lineage that included dinosaurs, provide valuable insights. Modern birds typically have fewer taste buds than mammals – chickens possess around 350 taste buds compared to humans’ approximately 10,000. These avian taste buds are primarily concentrated on the roof and floor of the mouth and the back of the tongue, rather than across the entire tongue surface as in mammals. If dinosaurs followed similar patterns, they likely had taste receptors distributed throughout their oral cavities but in smaller numbers than modern mammals. The actual morphology of dinosaur tongues, recently studied through hyoid bone analysis, suggests many dinosaurs had less mobile tongues than previously thought, potentially affecting how they experienced taste sensations.

Sweet Sensations: Could Dinosaurs Taste Sugar?

The ability to taste sweetness is linked to specific taste receptor genes, particularly the T1R2 and T1R3 genes that form sweet taste receptors in vertebrates. Interestingly, genetic studies have revealed that many modern birds lack functional T1R2 genes, suggesting they cannot taste sweetness in the same way mammals do. Since birds evolved directly from theropod dinosaurs, this raises questions about whether dinosaurs could detect sweet flavors. However, the picture is more complex than a simple yes or no. The loss of sweet taste reception in birds appears to have occurred after the dinosaur-bird split, meaning dinosaurs might have retained this ability. Herbivorous dinosaurs, in particular, would have benefited from detecting sugars in fruits and plants, suggesting they may have maintained sweet taste receptors even if their carnivorous relatives lost this ability through evolutionary specialization.

Sour Sensitivity in Ancient Reptiles

Sour taste perception, which helps identify potentially harmful acids and unripe fruits, appears to be one of the most evolutionarily conserved taste sensations. Modern birds, crocodilians, and most vertebrates can detect sour flavors through ion channels in their taste cells, particularly the ASIC and PKD2L1 channels. Given the widespread presence of sour taste reception across the vertebrate family tree, dinosaurs almost certainly possessed the ability to detect acidic compounds. This capability would have been particularly valuable for fruit-eating dinosaurs, helping them distinguish between nutritious ripe fruits and potentially harmful unripe ones. Fossil evidence of coprolites (fossilized feces) containing fruit remains suggests some dinosaurs indeed consumed fruits, implying they likely had mechanisms to identify suitable fruit ripeness. The persistence of sour taste detection across diverse modern species strongly supports the hypothesis that dinosaurs could detect sour flavors, perhaps with sensitivity comparable to today’s reptiles and birds.

Bitterness Detection as a Survival Mechanism

The ability to detect bitterness serves as a critical defense mechanism across the animal kingdom, warning creatures away from potentially toxic substances. Modern birds possess functional bitter taste receptors (T2Rs), though fewer varieties than mammals. Genomic studies indicate these receptors evolved early in vertebrate history, suggesting dinosaurs almost certainly could detect bitter compounds. For herbivorous dinosaurs consuming vast quantities of plant material, bitter taste reception would have been essential for avoiding toxic plants containing alkaloids and other defensive compounds. Evidence from fossilized stomach contents reveals selective feeding patterns among herbivorous dinosaurs, indicating they could distinguish between different plant types. The evolutionary pressure to avoid poisonous vegetation would have strongly favored the maintenance of bitter taste reception throughout dinosaur lineages, making this perhaps the most likely taste sensation to have been well-developed in these ancient creatures.

The Spice Question: Could Dinosaurs Detect Capsaicin?

Spiciness, unlike sweet, sour, or bitter tastes, isn’t technically a taste but a pain response triggered by compounds like capsaicin binding to heat-sensitive receptors called TRPV1 channels. These receptors evolved primarily as a defense mechanism against physical heat damage. Birds possess TRPV1 receptors but have mutations making them insensitive to capsaicin, which explains why birds can happily consume spicy peppers that mammals find painfully hot. This bird-specific mutation appears to have evolved after the dinosaur era, suggesting dinosaurs may have been sensitive to capsaicin-like compounds. However, this point is somewhat moot from a practical perspective, as plants producing capsaicin (notably peppers from the Capsicum genus) didn’t evolve until approximately 19 million years ago – long after dinosaurs went extinct. While dinosaurs likely possessed the physiological equipment to potentially detect spicy compounds, they would never have encountered modern spicy foods in their environment.

Salt Perception in the Mesozoic Era

Salt detection is fundamental to maintaining electrolyte balance and is present across virtually all vertebrate species. Modern birds possess functional salt taste receptors, primarily the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), allowing them to detect and seek out necessary sodium sources. Given salt’s essential role in physiological functions and the conservation of salt taste reception across the evolutionary tree, dinosaurs almost certainly could detect and respond to salty tastes. For herbivorous dinosaurs in particular, active salt-seeking behavior would have been necessary, as plant diets are typically sodium-poor. Fossil evidence shows dinosaurs sometimes congregated around ancient salt licks and mineral deposits, similar to how modern herbivores seek out salt sources. The physiological requirement for sodium, combined with the presence of salt detection mechanisms in dinosaurs’ closest living relatives, provides strong evidence that dinosaurs possessed salt taste reception comparable to modern birds and reptiles.

Umami: The Protein Taste for Carnivorous Dinosaurs

Umami, the savory taste associated with protein-rich foods, is detected through the T1R1 and T1R3 taste receptors in modern vertebrates. This taste sensation helps animals identify foods rich in amino acids and proteins, making it particularly valuable for carnivores. Modern birds possess functional umami receptors, suggesting this taste perception has been conserved throughout archosaur evolution. For carnivorous dinosaurs like Velociraptor or Tyrannosaurus rex, umami taste detection would have been especially valuable in identifying protein-rich food sources and assessing meat quality. Fossil evidence of predatory behavior and carnivory throughout the dinosaur lineage suggests these animals needed mechanisms to evaluate prey quality. The presence of umami taste reception in both birds and crocodilians, the closest living relatives of dinosaurs, strongly supports the hypothesis that dinosaurs – especially carnivorous species – could detect and respond to savory, protein-rich flavors.

Comparing Dinosaur Taste to Modern Reptiles

Modern reptiles offer another window into potential dinosaur taste capabilities, though they’re more distantly related to dinosaurs than birds are. Reptiles like alligators and crocodiles possess well-developed taste systems with receptors for sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami flavors, though their taste bud count is lower than in mammals. Crocodilians, as archosaurs sharing a common ancestor with dinosaurs, provide particularly relevant comparisons. They possess approximately 2,000-4,000 taste buds, concentrated primarily in the back of the oral cavity. Interestingly, some reptiles demonstrate unexpected taste preferences – certain turtles and lizards show strong attraction to sweet flavors, while others respond primarily to protein-rich tastes. If dinosaurs followed reptilian patterns, their taste systems would have been functional but perhaps less sensitive than those of mammals, with specific taste preferences likely varying between herbivorous, omnivorous, and carnivorous species. This comparative evidence suggests dinosaurs possessed comprehensive taste capabilities, though potentially with different sensitivity thresholds than modern mammals.

How Dinosaur Diets Shaped Their Taste Perception

An animal’s diet exerts strong evolutionary pressure on its taste system, potentially enhancing detection of beneficial flavors while reducing sensitivity to irrelevant ones. Herbivorous dinosaurs like Stegosaurus or Triceratops likely maintained robust sweet, bitter, and sour taste reception to help identify nutritious plants while avoiding toxic ones. Their taste receptors may have been specially tuned to detect plant compounds relevant to their specific diets. Carnivorous dinosaurs, meanwhile, would have benefited most from umami and salt detection, helping them identify protein-rich prey and fulfill electrolyte needs. Fossil evidence from theropod dinosaurs shows specialized teeth and jaws for meat consumption, suggesting their sensory systems likewise specialized for carnivory. Omnivorous dinosaurs such as Gallimimus would likely have maintained the most balanced taste system, capable of evaluating both plant and animal food sources. This dietary specialization suggests dinosaur taste perception wasn’t uniform across species but rather adapted to each creature’s ecological niche and feeding strategies.

Genomic Insights into Ancient Taste Capabilities

While extracting and analyzing actual dinosaur DNA remains impossible due to degradation over time, comparative genomics offers valuable insights into dinosaur sensory capabilities. By studying taste receptor genes in birds and crocodilians, scientists can identify which genes were likely present in their common ancestor – the archosaurs from which dinosaurs evolved. Recent research has identified several key taste receptor genes that appear to have been present in early archosaurs, including functional umami, bitter, and sour taste receptors. The evolutionary trajectory of sweet taste receptors is more complicated, with evidence suggesting the T1R2 sweet receptor was present in early archosaurs but subsequently lost in some bird lineages. By mapping these genetic patterns, researchers can reconstruct the likely taste receptor repertoire of dinosaurs with increasing confidence. These genomic approaches, combined with fossil evidence and comparative anatomy, continue to refine our understanding of dinosaur sensory experiences, suggesting they possessed sophisticated, if somewhat different, taste perception compared to modern mammals.

The Limitations of Studying Prehistoric Senses

Despite scientific advances, reconstructing dinosaur sensory experiences faces significant challenges that limit definitive conclusions. The soft tissues containing taste receptors almost never fossilize, leaving no direct evidence of dinosaur taste buds or their distribution. Scientists must rely on indirect methods like comparative anatomy with living relatives, evolutionary modeling, and rare instances of preserved stomach contents or coprolites. Even when comparing dinosaurs to modern birds and reptiles, we must acknowledge that 66+ million years of separate evolution has created substantial differences between these groups. Environmental factors during the Mesozoic Era, including different plant compounds and atmospheric compositions, may have created selection pressures for taste reception that no longer exist. Additionally, taste perception involves not just peripheral receptors but also complex brain processing, which cannot be directly studied in extinct species. These limitations mean that while science can make increasingly educated hypotheses about dinosaur taste capabilities, some aspects will likely remain speculative unless revolutionary new fossil evidence or analytical techniques emerge.

Future Research Directions

The study of dinosaur sensory capabilities continues to advance through innovative research approaches. New fossil preparation techniques occasionally reveal preserved soft tissue impressions that might one day include taste-related structures. Advanced scanning technologies like synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy allow increasingly detailed examination of fossil cranial structures, potentially revealing nerve pathways related to taste organs. Ongoing genetic research in birds, crocodilians, and other reptiles continues to illuminate the evolutionary history of taste receptor genes, providing clearer pictures of what genes existed in the dinosaur era. Experimental studies with modern birds, manipulating their environments and diets, help scientists understand how taste perception influences feeding behavior in dinosaurs’ closest living relatives. Computer modeling of dinosaur feeding mechanics, combined with ecological reconstructions of ancient food sources, may further clarify the selective pressures shaping dinosaur taste evolution. While the exact nature of dinosaur taste perception may never be fully known, interdisciplinary approaches continue to narrow the gap in our understanding of these fascinating creatures’ sensory worlds.

While we may never know exactly how a Triceratops experienced the taste of prehistoric vegetation or whether a Tyrannosaurus could distinguish subtle flavors in its prey, scientific evidence increasingly suggests dinosaurs possessed meaningful taste perception. Their taste capabilities likely included some combination of bitter, sour, salty, and umami sensations, with sweet perception possible in at least some species. Their taste experiences would have differed significantly from our own – probably less sensitive in terms of receptor density but evolutionarily optimized for their specific ecological niches and survival needs. As with all aspects of paleontology, our understanding continues to evolve with new discoveries and analytical approaches. What remains clear is that dinosaurs, like all successful animals, possessed sensory systems that helped them navigate their environment, find appropriate nutrition, and avoid dangers – systems that included meaningful, if alien, experiences of taste.