In the murky waters of prehistoric North America, an apex predator lurked that was so massive and fearsome it could prey upon dinosaurs. This was Deinosuchus, a giant crocodilian that dominated coastal environments during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 82 to 73 million years ago. Far larger than any modern crocodile or alligator, these “terrible crocodiles” (as their name translates from Greek) were truly extraordinary creatures that played a significant role in their ancient ecosystems. Their remains have fascinated paleontologists for generations, providing insights into a time when reptiles ruled both land and water. Let’s explore the remarkable world of Deinosuchus – the crocodile so formidable it could count dinosaurs among its prey.

The Discovery and Naming of Deinosuchus

The scientific journey of Deinosuchus began in the 1850s when fragmentary remains were first discovered in North Carolina. However, the genus wasn’t formally named until 1909 when paleontologist W.J. Holland studied massive crocodilian teeth and vertebrae from Montana. The name Deinosuchus, derived from the Greek words “deinos” (terrible) and “soukhos” (crocodile), perfectly captures the fearsome nature of this prehistoric predator. Early discoveries consisted primarily of isolated teeth, vertebrae, and armor plates, making it difficult for scientists to accurately reconstruct the animal. It wasn’t until more complete skull material was found in Texas during the mid-20th century that researchers began to understand the true nature and size of this massive crocodilian. Today, numerous Deinosuchus specimens have been discovered across the southern United States and northern Mexico, allowing paleontologists to develop a much clearer picture of this remarkable creature.

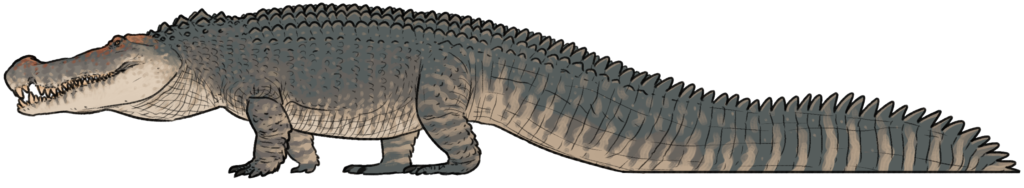

Size and Physical Characteristics

Deinosuchus was truly gigantic by any standard, dwarfing even the largest modern crocodilians. Conservative estimates place adult Deinosuchus at lengths of 33 to 39 feet (10 to 12 meters) and weights potentially exceeding 8 tons. Unlike some exaggerated depictions in popular media, paleontologists have determined these measurements based on careful scaling from partial remains and comparisons with modern relatives. The creature possessed a broad, robust skull measuring up to 6 feet (1.8 meters) in length, equipped with powerful jaws and conical teeth designed for gripping and crushing. Its body was protected by thick osteoderms (bony plates embedded in the skin) that formed a formidable armor along its back and neck. Interestingly, Deinosuchus had an expanded and bulbous snout tip with large holes that likely housed pressure receptors, suggesting adaptations for detecting prey movements in water. This combination of immense size, protective armor, and specialized sensory equipment made Deinosuchus one of the most formidable predators of its time.

Evolutionary Relationships

Deinosuchus belongs to Alligatoroidea, the same evolutionary group that includes modern alligators and caimans, rather than true crocodiles. This relationship has been established through a detailed examination of skull features, particularly the arrangement of teeth and palate structures that align more closely with alligatoroids than crocodyloids. Recent phylogenetic analyses suggest Deinosuchus was not a direct ancestor of modern alligators but rather represented a specialized side branch that evolved gigantism. The genus appears to have evolved from smaller alligatoroid ancestors, undergoing dramatic size increases over millions of years in response to available ecological niches. Researchers have identified at least two species within the genus: Deinosuchus riograndensis from Texas and northern Mexico, and Deinosuchus rugosus from the eastern United States. Some paleontologists have proposed a third species, Deinosuchus hatcheri, though debate continues about whether these represent distinct species or variations within a single species. Understanding Deinosuchus’s evolutionary position provides important insights into the development of giant predators and the diversification of crocodilians through time.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Deinosuchus inhabited coastal environments along the western shore of the Western Interior Seaway, a vast inland sea that divided North America into eastern and western landmasses during the Late Cretaceous period. Fossil evidence places these giant predators in what is now Texas, Montana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and northern Mexico. The environments these creatures dominated were typically brackish coastal wetlands, river deltas, and estuaries where fresh water met the sea. These productive ecosystems would have provided abundant prey and suitably deep waters for a predator of such enormous size. The geographic distribution of fossils suggests that different Deinosuchus species may have occupied different regions, with D. rugosus primarily found along the eastern coastline and D. riograndensis concentrated in the Texas-Mexico region. Climate modeling indicates these areas experienced warm, subtropical conditions during the Late Cretaceous, creating favorable environments for large ectothermic predators that relied on external heat sources to maintain their metabolism.

Hunting and Feeding Behavior

As an apex predator, Deinosuchus employed hunting strategies similar to those of modern crocodilians, but on a far more massive scale. These enormous hunters likely ambushed prey from the water, using their powerful tails to launch lightning-fast strikes. Bite mark evidence on dinosaur fossils provides compelling proof that Deinosuchus preyed upon dinosaurs, including large ornithischians and theropods that came to the water’s edge to drink. The creature’s robust teeth and incredibly powerful bite force enabled it to grasp and dismember even heavily armored prey. Like modern crocodilians, Deinosuchus probably employed the “death roll” technique, rapidly spinning in the water to tear chunks from prey too large to swallow whole. Beyond dinosaurs, its diet likely included fish, turtles, and other aquatic creatures that shared its habitat. Isotopic analysis of Deinosuchus teeth suggests these predators may have also been opportunistic scavengers when the opportunity presented itself, making them versatile hunters that could exploit multiple food sources within their environments.

The Dinosaur Menu: Specific Prey Evidence

Paleontological evidence provides fascinating insights into the specific dinosaurs that fell prey to Deinosuchus. Several hadrosaur (duck-billed dinosaur) fossils have been discovered bearing distinctive bite marks that match the size and spacing of Deinosuchus teeth, confirming these plant-eaters were on the menu. In what is now Texas, researchers have found theropod dinosaur bones with similar predation marks, suggesting even carnivorous dinosaurs weren’t safe from these aquatic predators. One particularly compelling specimen includes a large titanosaur vertebra bearing bite marks consistent with Deinosuchus, indicating these massive crocodilians occasionally attacked sauropods, perhaps targeting juveniles or weakened individuals. Turtle shells from the Late Cretaceous frequently show catastrophic damage patterns matching Deinosuchus bite profiles, demonstrating that even armored prey couldn’t withstand the crushing power of these predators’ jaws. The diversity of prey items identified through bite mark analysis reveals Deinosuchus as an ecological generalist that could successfully hunt across multiple dinosaur groups and size classes, establishing it as one of the most versatile predators in Late Cretaceous ecosystems.

Growth and Lifespan

The growth pattern of Deinosuchus followed trends similar to modern crocodilians but extended over a much longer timeframe to reach its enormous adult size. Through histological examination of bone tissue microstructure, paleontologists have determined that Deinosuchus likely required 35 to 50 years to reach full maturity, a significantly longer growth period than modern alligators. Growth rings in fossilized bones suggest these creatures experienced seasonal variations in growth rates, potentially slowing during cooler months and accelerating during warmer periods. Based on comparisons with modern relatives, scientists estimate Deinosuchus may have lived 50 to 80 years in total, making them exceptionally long-lived reptiles. The extended growth period explains how Deinosuchus achieved such massive proportions, with juveniles growing steadily for decades before reaching sexual maturity. Size-based analysis suggests young Deinosuchus likely occupied different ecological niches than adults, feeding on smaller prey until they grew large enough to tackle dinosaurs, thereby reducing competition between generations.

Unique Anatomical Features

Beyond its enormous size, Deinosuchus possessed several specialized anatomical features that distinguished it from both modern crocodilians and its prehistoric relatives. The most distinctive characteristic was its unusually broad, inflated snout with large holes at the tip that housed pressure-sensitive organs called integumentary sense organs (ISOs). These sensory structures, more developed than in modern crocodilians, would have enhanced Deinosuchus’s ability to detect minute water movements and vibrations from potential prey. The creature’s teeth showed specialization as well, with slightly blunter, more robust teeth in the back of the jaw for crushing hard materials like turtle shells and bones. Examination of the skull structure reveals particularly large attachment sites for jaw muscles, indicating an extraordinarily powerful bite force that some estimates place at over 23,000 pounds per square inch – several times stronger than even the largest modern crocodilians. The osteoderms (protective bony plates) of Deinosuchus were unusually thick and featured distinctive pit configurations not seen in other crocodilians, suggesting a highly specialized defensive adaptation against large dinosaurian predators that might have attempted to prey on smaller individuals.

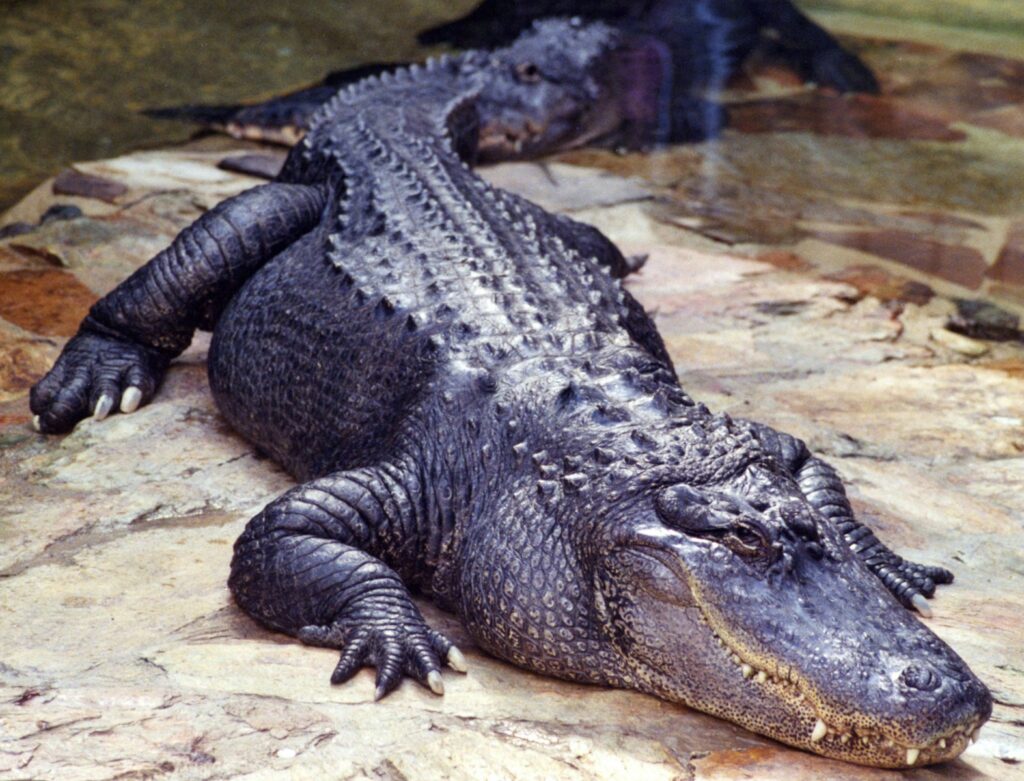

Deinosuchus Compared to Modern Crocodilians

While Deinosuchus shared many features with its modern relatives, the scale and specifics of its adaptations were dramatically amplified. Modern American alligators typically reach lengths of 10-15 feet and weights of around 1,000 pounds at maximum, making Deinosuchus approximately three times longer and potentially fifteen times heavier than its largest modern descendants. The skull proportions differed significantly as well, with Deinosuchus having a broader, more robust skull relative to its body size compared to modern species. Both ancient and modern forms share similar basic hunting strategies involving ambush predation, but Deinosuchus operated on a much grander scale, capable of taking down prey that would be impossible for even the largest modern crocodilians. Physiologically, both likely functioned as ectotherms (cold-blooded animals), but Deinosuchus’s larger body mass would have provided greater thermal inertia, potentially allowing it to maintain more stable body temperatures over time. Despite these differences, the fundamental crocodilian body plan has remained remarkably consistent over 80 million years, testifying to the evolutionary success of this ancient design.

Ecological Impact

As an apex predator of tremendous size, Deinosuchus exerted significant influence over Late Cretaceous ecosystems throughout its range. By preying on large dinosaurs, these giant crocodilians helped regulate herbivore populations, potentially preventing overgrazing of coastal vegetation. Their presence would have shaped the behavior of dinosaurs and other animals in the region, likely causing many species to develop cautious approaches to water sources where these predators lurked. Evidence suggests Deinosuchus created what ecologists call a “landscape of fear,” where potential prey animals altered their movements and behaviors specifically to avoid these dangerous predators. As both hunters and occasional scavengers, they would have played a crucial role in nutrient cycling within coastal ecosystems, breaking down carcasses and redistributing energy through the food web. Additionally, juvenile Deinosuchus likely occupied different ecological niches than adults, filling multiple predatory roles within the same ecosystem as they grew. This ecological versatility and multi-level impact demonstrate why Deinosuchus represents one of the most significant predators of the Late Cretaceous period.

Extinction and Legacy

Deinosuchus disappeared from the fossil record approximately 73 million years ago, well before the mass extinction event that claimed the non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous period. This earlier extinction remains somewhat mysterious, though several hypotheses have been proposed to explain it. Changes in sea level and shifting coastlines may have eliminated the specific brackish water habitats that Deinosuchus depended upon, forcing these specialized giants into less suitable environments. Competition from emerging new predators or changes in prey availability could have created additional pressures. Climate fluctuations during this period might have pushed environmental conditions beyond the tolerance range for such large ectothermic predators. Despite their extinction, the evolutionary legacy of Deinosuchus continued through smaller alligatoroid relatives that eventually gave rise to modern alligators and caimans. The ecological niche that Deinosuchus occupied – that of a massive semi-aquatic predator capable of taking large terrestrial animals – has never been completely refilled in North American ecosystems, making this creature a unique evolutionary experiment in predator gigantism.

Deinosuchus in Popular Culture

Despite not achieving the same level of fame as Tyrannosaurus rex or Velociraptor, Deinosuchus has made notable appearances in various media that have helped introduce this prehistoric giant to public consciousness. The creature featured prominently in the BBC documentary series “Walking with Dinosaurs: The Ballad of Big Al,” where it was depicted hunting dinosaurs along riverbanks. Several documentary programs, including those from National Geographic and the Discovery Channel, have highlighted Deinosuchus as one of history’s most formidable predators, often reconstructing its hunting behaviors based on modern crocodilian studies. In the realm of fiction, Deinosuchus has appeared in novels such as “Meg: Hell’s Aquarium” by Steve Alten and has been featured in various prehistoric-themed video games, including “Ark: Survival Evolved,” where players can encounter and even tame these massive creatures. Children’s books about prehistoric life frequently include Deinosuchus, typically emphasizing its status as “the crocodile that ate dinosaurs” – a compelling hook that captures young imaginations. This cultural presence, while not as extensive as that of some dinosaurs, has helped establish Deinosuchus as an iconic representative of prehistoric crocodilians in public understanding.

Recent Research and New Discoveries

Our understanding of Deinosuchus continues to evolve as new specimens are discovered and advanced analytical techniques are applied to existing fossils. A groundbreaking 2020 study published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology clarified the taxonomy of Deinosuchus, confirming three distinct species and providing new details about their geographical distribution and physical characteristics. Recent computed tomography (CT) scanning of Deinosuchus skull material has revealed previously unknown details about the brain case structure and sensory capabilities, suggesting these animals had particularly acute senses adapted for hunting in murky waters. Isotopic analysis of tooth enamel has provided new insights into Deinosuchus’ diet and habitat preferences, confirming these predators moved between freshwater and brackish environments throughout their lives. Paleontologists working in the southwestern United States uncovered new Deinosuchus specimens in 2018 that included rare preserved stomach contents, providing direct evidence of their prey selection rather than relying solely on bite mark analysis. The application of biomechanical modeling to Deinosuchus’ jaw structure has yielded more precise estimates of bite force and feeding mechanics, helping researchers understand how these animals dispatched their formidable prey. These ongoing discoveries continue to refine our picture of this remarkable predator and its role in Late Cretaceous ecosystems.

Conclusion

Deinosuchus stands as a testament to the remarkable diversity of prehistoric life and the different forms dominance could take in ancient ecosystems. While dinosaurs ruled the terrestrial realm, these massive crocodilians controlled the waterways and shorelines, creating a complex predatory relationship that shaped animal behaviors and evolution. Their enormous size, specialized hunting adaptations, and ability to prey upon dinosaurs make them one of the most fascinating predators in Earth’s history. Though they vanished millions of years before the dinosaur extinction, their evolutionary legacy persists in the modern alligators and caimans that inhabit the Americas today. As research continues, we gain ever clearer insights into these magnificent creatures that once patrolled ancient coastlines, reminding us that dinosaurs weren’t the only remarkable reptiles of the Mesozoic Era. Deinosuchus truly earned its fearsome reputation as “the crocodile that ate dinosaurs.”