In the sun-baked landscapes of what would eventually become modern-day Texas, a formidable creature once patrolled the prehistoric terrain. With its heavily armored body and imposing shoulder spikes, Desmatosuchus commanded respect among the fauna of the Late Triassic period, approximately 228 to 208 million years ago. This remarkable archosaur, whose name translates to “link crocodile,” provides a fascinating window into a world long before dinosaurs dominated the landscape. Its fossils, first discovered in the early 20th century, continue to enlighten paleontologists about the diverse evolutionary paths of archosaurs and the complex ecosystems of Triassic North America.

Taxonomic Classification and Evolutionary Significance

Desmatosuchus belongs to the clade Aetosauria, a group of heavily armored, herbivorous to possibly omnivorous archosaurs that flourished during the Late Triassic period. Taxonomically, it sits within Pseudosuchia, the “crocodile-line” archosaurs, rather than with the Avemetatarsalia that would eventually give rise to dinosaurs and birds. This positioning makes Desmatosuchus an important figure in understanding archosaur diversification following the Permian-Triassic extinction event. The genus includes several species, with Desmatosuchus spurensis being the type species described by Ermine Cowles Case in 1920. Its evolutionary adaptations represent a unique solution to survival in the competitive ecosystems of the Triassic, demonstrating how armor and specialized feeding strategies allowed these creatures to thrive in a world increasingly dominated by early dinosaurs and other archosaurs.

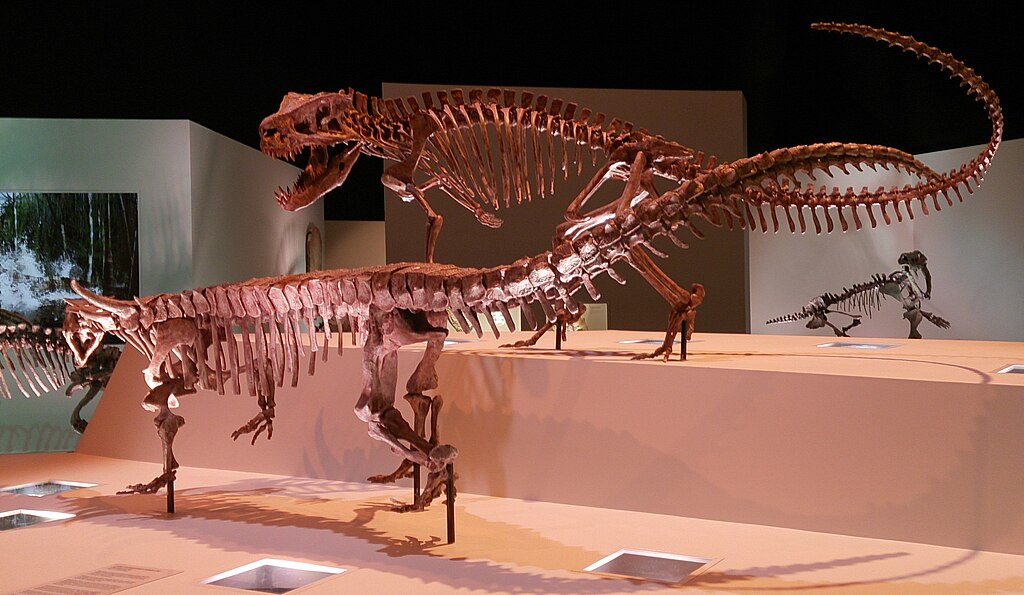

Discovery and Fossil History

The first Desmatosuchus specimens were unearthed from the Dockum Group in Texas by paleontologist E.C. Case in the early 1920s. This landmark discovery revealed an animal unlike any previously known, with distinctive armor plates and elongated shoulder spikes that immediately captured scientific attention. Since then, additional fossils have been recovered across the southwestern United States, particularly in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, primarily from the Chinle Formation and equivalent strata. The quality of preservation has been remarkable in some cases, providing near-complete skeletons that allow for detailed anatomical study. Each new discovery has refined our understanding of this animal’s morphology and ecological niche. Notable specimens include an exceptionally well-preserved skeleton found in Crosby County, Texas, which has become a reference point for understanding aetosaur anatomy and has been displayed at prominent natural history museums.

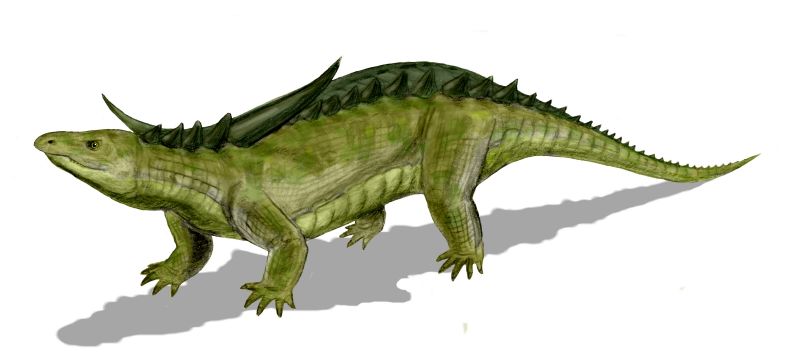

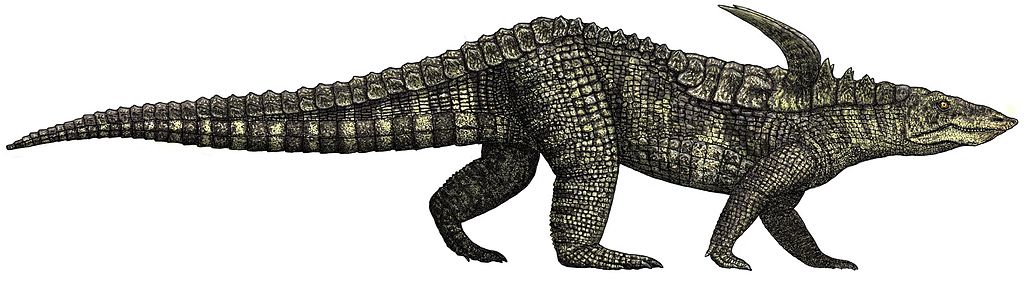

Physical Appearance and Size

Desmatosuchus presented an imposing figure, measuring approximately 4.5 meters (15 feet) in length and weighing around 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds). Its body was low-slung and robust, supported by four powerful limbs positioned in a semi-sprawling stance typical of early archosaurs. The creature’s most distinctive feature was undoubtedly its elaborate defensive armor, consisting of interlocking bony plates called osteoderms that covered its back, sides, and tail in a protective carapace. Most striking were the two massive, curved spikes extending from its shoulders, which could reach over 40 centimeters (16 inches) in length. These formidable projections would have made Desmatosuchus appear even larger and more threatening to potential predators. Its somewhat pig-like snout ended in a shovel-shaped projection that was likely used for digging or uprooting plants, suggesting specialized feeding behaviors unlike those of contemporary archosaurs.

Armor and Defense Mechanisms

The defensive adaptations of Desmatosuchus represent some of the most sophisticated armor seen in any Triassic vertebrate. Its body was encased in rows of bony osteoderms arranged in precise patterns, with different shapes for different body regions. The dorsal osteoderms featured distinctive pits and ridges, creating a textured surface that may have provided additional strength while minimizing weight. The creature’s most dramatic defensive features were the paired shoulder spikes, which curved upward and outward from the body in a sweeping arc. These impressive structures likely served multiple purposes: deterring predators, possibly being used in intraspecific combat or display, and perhaps even aiding in thermoregulation by increasing surface area. The armor pattern continued down the tail, where slightly smaller but still prominent spikes would have made Desmatosuchus a challenging meal for even the largest predators of its time, such as early rauisuchians and phytosaurs.

Skull and Feeding Adaptations

The skull of Desmatosuchus reveals fascinating insights into its lifestyle and ecological niche. Unlike the sharp-toothed skulls of carnivorous archosaurs, Desmatosuchus possessed a relatively short, upturned snout with small, leaf-shaped teeth suitable for processing plant material. The anterior portion of the snout was expanded into a shovel-like structure that would have been effective for digging and uprooting vegetation. Analysis of jaw mechanics suggests that Desmatosuchus had a relatively weak bite force compared to carnivorous contemporaries, but its jaw design was well-suited for cropping plants and possibly crushing tougher vegetable matter. Interestingly, some paleontologists have proposed that the animal may have supplemented its primarily herbivorous diet with small animals or insects, making it potentially omnivorous. The positioning of the eyes on the skull indicates a wide field of vision, allowing Desmatosuchus to monitor its surroundings while feeding—a valuable adaptation for a relatively slow-moving animal vulnerable to predation.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Desmatosuchus inhabited the tropical to subtropical regions of western Pangaea, specifically in what would later become the southwestern United States. Paleoenvironmental evidence suggests it lived in a seasonally wet, semi-arid landscape characterized by braided rivers, floodplains, and temporary lakes. The climate of the Late Triassic in this region featured distinct wet and dry seasons, creating a challenging environment that required specialized adaptations. Desmatosuchus fossils have been discovered primarily in the Chinle Formation and equivalent strata across Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, with the richest deposits found in the Dockum Group of Texas. This distribution indicates that while Desmatosuchus was successful in its ecological niche, it was geographically restricted compared to some other Triassic archosaurs. The consistent association of its remains with specific sedimentary environments suggests Desmatosuchus preferred riparian habitats near waterways, where vegetation would have been more abundant and accessible throughout the year.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Evidence from tooth morphology, jaw structure, and the distinctive shovel-shaped snout strongly suggests that Desmatosuchus was primarily herbivorous, though potentially opportunistically omnivorous. Its small, leaf-shaped teeth were well-suited for cropping vegetation rather than tearing flesh, and wear patterns on fossil teeth indicate they were used for processing fibrous plant material. The shovel-like expansion at the front of the snout would have been an effective tool for digging up roots, tubers, and rhizomes, which likely constituted a significant portion of its diet during drier seasons when surface vegetation was scarce. Some paleontologists have proposed that Desmatosuchus may have used its specialized snout to dig for invertebrates in the soil or rotting logs, supplementing its plant-based diet with protein. The substantial gut capacity suggested by its broad ribcage would have accommodated the fermentation processes necessary for digesting tough plant material, similar to modern herbivorous reptiles and mammals.

Locomotion and Movement Patterns

The limb structure of Desmatosuchus reveals an animal that was robust but not particularly fast-moving. Its legs were powerfully built and positioned in a semi-sprawling stance typical of early archosaurs rather than the more upright posture seen in later dinosaurs and crocodilians. Biomechanical analysis suggests that Desmatosuchus would have moved with a deliberate gait, capable of sustained walking but not rapid running. The heavy armor covering its body would have further limited its speed and agility, making flight from predators an unlikely defense strategy. Instead, Desmatosuchus relied on its formidable protective plates and spikes to deter attacks. Fossil trackways potentially attributable to aetosaurs indicate a wide-gauge walking pattern, with the feet placed well apart from the body’s midline. This stable stance would have been advantageous for an animal navigating varied terrain, from soft riverbanks to the firmer ground of floodplains, as it foraged for food.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

While direct evidence of Desmatosuchus reproduction remains elusive, comparisons with other archosaurs provide insights into its probable life cycle. As an archosaur, Desmatosuchus likely laid amniotic eggs, possibly in excavated nests similar to those of modern crocodilians. The discovery of juvenile Desmatosuchus specimens indicates that young individuals already possessed the characteristic armor of adults, though proportionally less developed. Growth ring studies in aetosaur osteoderms suggest that these animals experienced cyclical growth, possibly corresponding to seasonal changes in their environment. Like many modern reptiles, Desmatosuchus likely exhibited indeterminate growth, continuing to increase in size throughout life, albeit at a decreasing rate with age. The substantial investment in defensive structures suggests that juvenile mortality was significant, likely due to predation, making the protective armor an essential adaptation from an early age.

Ecological Role and Interactions

Desmatosuchus occupied a crucial ecological niche as a medium to large-sized herbivore in the Late Triassic ecosystems of western Pangaea. Its ability to process tough plant material and extract nutrients from below-ground plant parts may have given it access to food resources unavailable to other contemporary herbivores. Fossil evidence shows that Desmatosuchus shared its habitat with a diverse community of archosaurs, including early dinosaurs, phytosaurs (crocodile-like river predators), rauisuchians (large terrestrial predators), and other aetosaurs. Tooth marks occasionally found on Desmatosuchus osteoderms suggest that despite its formidable defenses, it was sometimes targeted by large predators, particularly phytosaurs that might have ambushed it near waterways. As a primary consumer, Desmatosuchus would have played an important role in energy transfer through the food web and may have influenced vegetation patterns through its selective feeding behaviors.

Extinction and Legacy

Desmatosuchus and other aetosaurs disappeared from the fossil record by the end of the Triassic period, approximately 201 million years ago, coinciding with the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event. This major extinction eliminated many archosaur lineages and paved the way for dinosaur dominance in terrestrial ecosystems throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. The exact causes of aetosaur extinction remain debated, but likely include climate change, ecosystem restructuring, and possibly competition with emerging dinosaur herbivores that possessed more efficient feeding and locomotion adaptations. Despite their extinction, Desmatosuchus and its relatives represent a fascinating evolutionary experiment in herbivory and defense among early archosaurs. Their heavily armored body plan demonstrated a unique solution to survival that was successful for millions of years before changing conditions rendered their adaptations insufficient.

Significance in Paleontology

Desmatosuchus holds special significance in paleontological research as one of the most completely known non-dinosaurian archosaurs from the Late Triassic. Its distinctive morphology makes it an important index fossil for dating Triassic rock formations in the American Southwest, and its remains have contributed substantially to our understanding of archosaur evolution and diversity. The exceptional preservation of some specimens has allowed detailed study of soft tissue impressions, growth patterns, and pathologies, providing rare glimpses into the biology of these ancient animals. Additionally, Desmatosuchus represents an important case study in convergent evolution, as its heavily armored body plan evolved independently from superficially similar adaptations seen in later ankylosaur dinosaurs. Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of this remarkable creature, with new fossil discoveries and advanced analytical techniques revealing ever more details about its anatomy, physiology, and ecological relationships.

Modern Cultural Representation

Though less well-known than many dinosaurs, Desmatosuchus has found its place in popular culture and educational settings, particularly in exhibits focusing on Triassic ecosystems. Life-sized reconstructions of this impressive creature can be found in natural history museums across the southwestern United States, where they help visitors visualize the pre-dinosaur world of the Late Triassic. Its distinctive appearance, particularly the dramatic shoulder spikes, makes it a visually striking subject for paleoart and scientific illustrations. In Texas especially, Desmatosuchus has been embraced as an iconic prehistoric resident, featured in regional museum exhibits and educational programs about the state’s deep geological history. The creature has appeared in several documentary series about prehistoric life, helping to demonstrate that the Age of Dinosaurs was preceded by an equally fascinating period dominated by other remarkable archosaurs.

Desmatosuchus stands as a testament to the incredible diversity of life that has inhabited our planet through deep time. As we continue to unearth and study its remains, this armored archosaur from Triassic Texas offers valuable insights into evolution, adaptation, and the dynamic ecosystems that existed long before humans walked the Earth. Its legacy lives on not just in museum displays and scientific literature, but in our expanding understanding of life’s remarkable journey through the ages.