The ancient world of dinosaurs was a complex ecosystem filled with diverse species occupying various ecological niches. For over 165 million years, these remarkable reptiles dominated Earth’s terrestrial environments, evolving into creatures of astonishing variety in size, shape, diet, and behavior. When considering the question of whether dinosaurs had predators or were simply predators themselves, we must understand that dinosaurs weren’t a monolithic group but rather a diverse assemblage of animals that included both fearsome hunters and vulnerable prey. The dynamics of predator-prey relationships during the Mesozoic Era were intricate and evolved significantly over time, creating a fascinating narrative of adaptation, competition, and survival.

The Diversity of Dinosaur Species and Roles

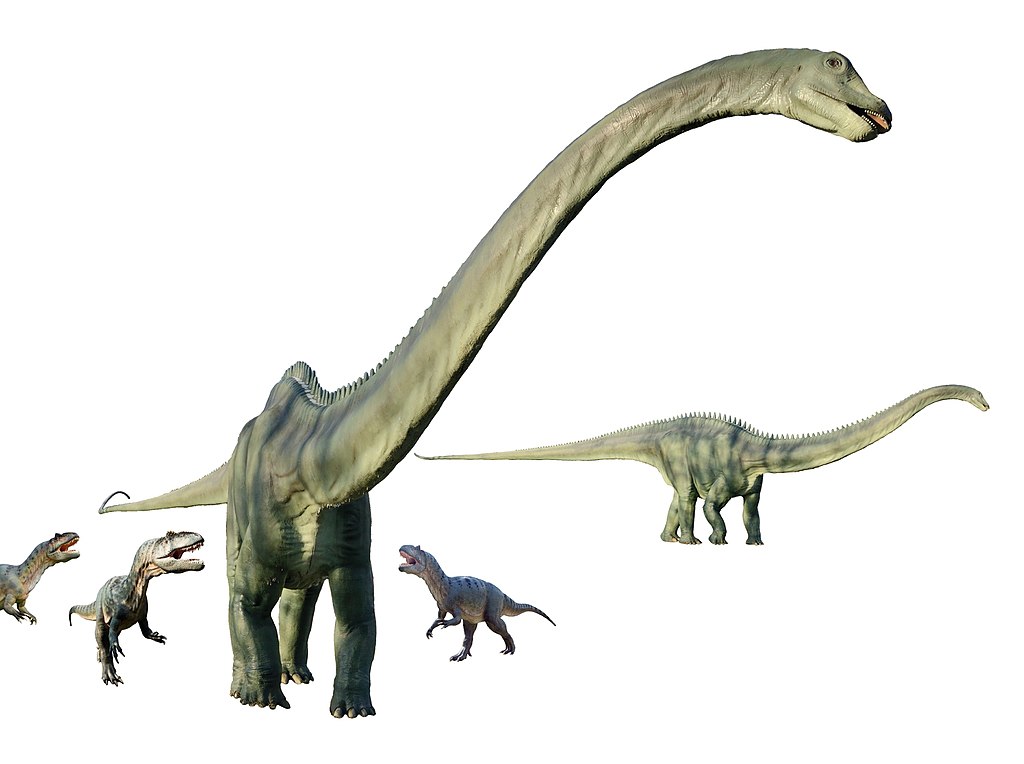

Dinosaurs evolved into numerous forms that filled virtually every ecological niche available in their world. From the massive sauropods like Brachiosaurus weighing up to 80 tons to small theropods like Compsognathus weighing just a few pounds, dinosaurs displayed remarkable diversity. This variety meant that different dinosaur species occupied different positions in the food chain. Some were apex predators that hunted other dinosaurs, while others were primary consumers that fed exclusively on plants. Many occupied middle trophic levels, both hunting smaller animals and being hunted by larger ones. This ecological stratification meant that many dinosaur species were simultaneously predators of some animals and prey for others, creating complex food webs rather than simple predator-prey hierarchies.

Apex Predators Among Dinosaurs

The most iconic dinosaur predators were the large theropods, bipedal carnivores that included famous species like Tyrannosaurus rex, Giganotosaurus, and Spinosaurus. These massive hunters represented the apex of dinosaur evolution as predators, equipped with powerful jaws lined with serrated teeth specialized for tearing flesh. T. rex, for example, possessed a bite force estimated at up to 35,000 newtons, powerful enough to crush bone. With keen senses, particularly vision, and bodies built for pursuing or ambushing prey, these predators hunted various other dinosaurs. Evidence from fossil discoveries, including bite marks on bones and occasional fossilized stomach contents, confirms that large theropods preyed upon other dinosaur species, establishing them firmly as predators rather than prey in most circumstances.

Who Preyed on the Predators?

While adult apex predators like T. rex had few threats from other animals, they weren’t entirely immune to predation throughout their lives. Juvenile theropods, being smaller and less formidable, were vulnerable to attacks from other predatory dinosaurs and prehistoric crocodilians. Paleontological evidence suggests cases of cannibalism among some theropod species, with larger individuals occasionally hunting smaller members of their own kind. Additionally, these top predators faced dangers from disease, injury, and environmental hazards that could weaken them enough to become vulnerable to opportunistic attacks. The fossil record occasionally reveals evidence of conflict between large predators, suggesting competition and potentially predatory behavior between different carnivorous species when size or circumstances permitted.

Herbivores as Prey and Their Defenses

The herbivorous dinosaurs, which made up the majority of dinosaur species, evolved sophisticated defenses against predation. Ceratopsians like Triceratops developed impressive horns and neck frills that served as defensive weapons and displays. Ankylosaurs evolved heavy body armor and tail clubs capable of delivering devastating blows to attackers. Stegosaurs possessed tail spikes called thagomizers that could inflict serious wounds on predators. Many herbivores also relied on herding behavior for protection, with safety in numbers increasing vigilance and defensive capabilities. These adaptations demonstrate the evolutionary arms race between predator and prey, with herbivorous dinosaurs constantly developing new defensive strategies to counter the hunting adaptations of their predators, showing that they were indeed prey species but not defenseless ones.

The Role of Non-Dinosaurian Predators

Dinosaurs shared their world with numerous other reptiles that acted as predators within the ecosystem. Prehistoric crocodilians grew to enormous sizes during the Mesozoic Era, with some species like Deinosuchus reaching lengths of up to 40 feet. These semi-aquatic ambush predators would have been capable of taking down even large dinosaurs that came to the water’s edge. Pterosaurs, while not dinosaurs, included carnivorous species that may have preyed on smaller dinosaurs and dinosaur hatchlings. Large marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs could have preyed on dinosaurs that ventured into or near water bodies. These non-dinosaurian predators added another layer of complexity to the predator-prey dynamics of the Mesozoic world, ensuring that even in environments where large theropod dinosaurs were absent, predation pressure remained a significant evolutionary force.

Predation on Dinosaur Eggs and Hatchlings

Perhaps the most vulnerable stage in any dinosaur’s life cycle was the egg and hatchling period. Fossil evidence from nesting sites shows that dinosaur eggs and newly hatched young faced numerous predators. Small theropods, primitive mammals, and even some lizards likely specialized in raiding dinosaur nests. The discovery of Oviraptor fossils near nests initially led to misinterpretation of these dinosaurs as egg thieves, though later evidence suggested they were actually brooding their own eggs. Even the largest dinosaur species began life as relatively small, vulnerable hatchlings that needed to evade predators until they grew large enough for their size to offer protection. This vulnerability explains why many dinosaur species evolved parental care behaviors, with adults protecting nests and young from potential predators, demonstrating sophisticated reproductive strategies designed to counter predation pressure.

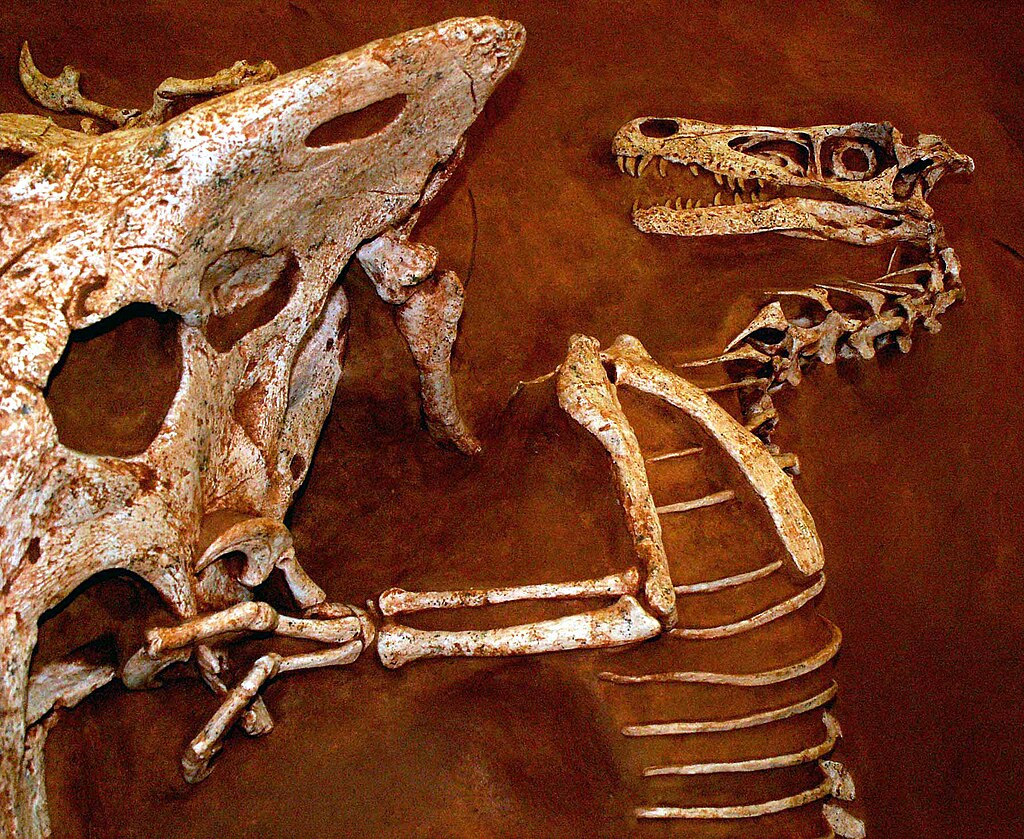

Mesopredators in the Dinosaur Age

The dinosaur ecosystem included numerous mesopredators—medium-sized carnivores that hunted smaller prey while potentially being hunted by larger predators themselves. Dinosaurs like Velociraptor and its relatives occupied this ecological niche, hunting small animals while avoiding larger theropods. These middle-level predators played crucial roles in regulating populations of small dinosaurs, early mammals, and other vertebrates. Fossil evidence, such as the famous “fighting dinosaurs” specimen showing a Velociraptor locked in combat with a Protoceratops, demonstrates these mesopredator-prey relationships in action. The abundance and diversity of mesopredator dinosaurs throughout the Mesozoic Era indicate they were highly successful at balancing the dual pressures of finding their own prey while avoiding becoming prey themselves, epitomizing the complex nature of dinosaur predator-prey dynamics.

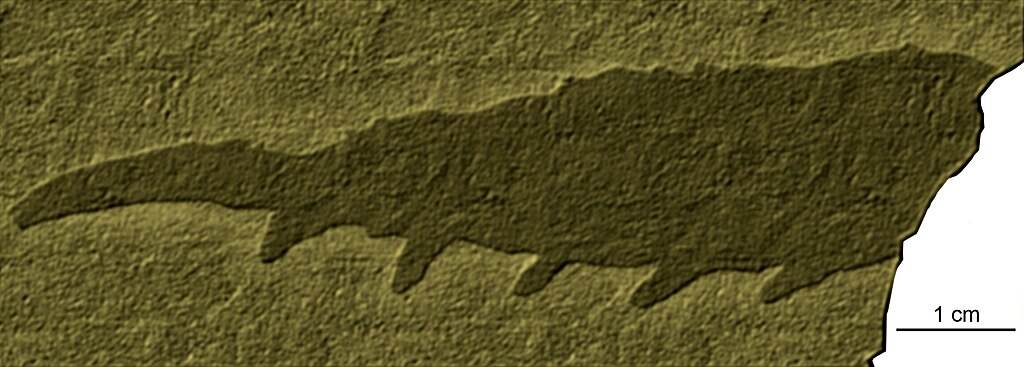

Evidence of Predation in the Fossil Record

Paleontologists have uncovered compelling evidence of predatory interactions between dinosaurs in the fossil record. Bite marks matching the dentition of specific predators have been found on the bones of herbivorous dinosaurs, sometimes with signs of healing that indicate the prey survived the attack. Theropod teeth have been discovered embedded in bones of potential prey species, broken off during feeding. Perhaps most dramatic are the rare instances of fossilized specimens captured in the act of predation, such as the small theropod Sinornithosaurus preserved with what appears to be its mammalian prey. Coprolites (fossilized feces) containing bone fragments can also provide evidence of predatory behavior and diet. These fossil clues, though rare, offer invaluable insights into the predator-prey relationships that shaped dinosaur evolution over millions of years.

Size as a Defense Mechanism

One of the most effective anti-predator adaptations among many dinosaur groups was gigantism—the evolution of extremely large body size. The massive sauropods, which included the largest land animals ever to have existed, likely achieved virtual immunity from predation once they reached adult size. Even the largest predatory theropods would have struggled to take down healthy adult sauropods, which could weigh over 70 tons. Fossil evidence suggests that predators like Allosaurus may have targeted juvenile sauropods instead, or attacked adults using pack hunting strategies or by exploiting injuries or illness. The repeated evolution of gigantism in multiple dinosaur lineages suggests that size was an effective defense against predation, though it came with significant metabolic costs and developmental vulnerabilities. These size-based dynamics shaped the evolutionary trajectories of both predator and prey dinosaur lineages throughout the Mesozoic.

Pack Hunting and Social Behavior

Evidence increasingly suggests that some predatory dinosaurs hunted in coordinated packs, allowing them to take down prey larger than any individual could handle alone. Fossil sites containing multiple specimens of the same predator species, such as Deinonychus and Allosaurus, hint at social hunting behavior. These pack-hunting strategies would have significantly altered predator-prey dynamics, enabling medium-sized predators to target much larger herbivores. In response, many herbivorous dinosaurs appear to have developed their own social behaviors, forming protective herds that increased vigilance and collective defense. Trackway fossils showing multiple individuals of the same species moving together provide evidence for these social groupings. The evolution of these complex social behaviors in both predatory and prey species represents a sophisticated escalation in the evolutionary arms race between dinosaur hunters and the hunted.

The Impact of Environmental Factors on Predation

Environmental conditions significantly influenced predator-prey dynamics among dinosaurs throughout the Mesozoic Era. During periods of environmental stress such as drought, predation pressure likely intensified as prey became concentrated around limited resources like water sources. Seasonal variations would have affected the vulnerability of certain species, with breeding seasons or migrations potentially creating windows of opportunity for predators. The gradual breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea throughout the Mesozoic created increasingly isolated landmasses with unique predator-prey dynamics evolving on each. Climate fluctuations throughout the dinosaur era altered vegetation patterns, indirectly affecting herbivore distributions and consequently predator behavior. These environmental factors created a dynamic ecological landscape where predator-prey relationships continually adjusted to changing conditions, driving adaptive radiation in both predatory and prey dinosaur lineages.

Specialized Hunting and Anti-Predator Adaptations

The evolutionary arms race between predatory dinosaurs and their prey produced increasingly specialized adaptations on both sides. Some predators evolved features specifically designed for particular hunting strategies—the sickle-shaped killing claws of dromaeosaurids for grappling with prey, the reinforced skulls of pachycephalosaurs potentially useful in defensive head-butting, or the extraordinary binocular vision of Troodon suggesting precision hunting capabilities. Prey species developed equally specialized defenses, from the chemical deterrents suggested in some hadrosaur species to the shock-absorbing osteoderms of ankylosaurs. The diversity of these adaptations indicates that predation was a powerful evolutionary force shaping dinosaur morphology. The constant feedback loop between predator innovation and prey counter-adaptation drove much of the morphological diversity we observe in the dinosaur fossil record, creating the spectacular variety of forms that continue to captivate scientific and public imagination.

The Shifting Balance Throughout Dinosaur History

Over the 165 million years of dinosaur dominance, the balance between predators and prey shifted significantly as new lineages evolved and others went extinct. The Late Triassic saw relatively small theropods like Coelophysis hunting equally modest prey, while the Jurassic Period witnessed the rise of massive predators like Allosaurus alongside the first giant sauropods. By the Late Cretaceous, specialized predator-prey relationships had evolved, with tyrannosaurs hunting ceratopsians and hadrosaurs in complex ecological webs. The fossil record shows episodic shifts in predator-prey ratios, with some time periods appearing to support more predator biomass than others. These long-term evolutionary dynamics reflect changing environmental conditions, continental arrangements, and the ongoing evolutionary innovations that characterized the dinosaur era. What remained constant throughout was that dinosaurs functioned as both predators and prey, creating a dynamic ecosystem of extraordinary complexity and duration.

Conclusion: A Complex Web of Predators and Prey

The question of whether dinosaurs were predators or prey ultimately resolves to a clear answer: they were both. Throughout their lengthy reign on Earth, dinosaurs developed into a rich tapestry of species occupying virtually every conceivable ecological niche. Some were specialized apex predators that faced few threats as adults but were vulnerable as juveniles. Others were primarily prey animals that evolved sophisticated defenses to survive in a world of formidable hunters. Most existed somewhere in the middle of this spectrum, both hunting and being hunted depending on their size, age, and circumstances. This complex web of predator-prey relationships drove much of dinosaur evolution, creating the remarkable diversity of forms we discover in the fossil record. Understanding these ecological dynamics gives us a richer appreciation of dinosaurs not simply as individual spectacular creatures, but as participants in a complex, dynamic ecosystem that flourished for an extraordinary span of Earth’s history.