When we think of dinosaurs, we often imagine these magnificent creatures ruling the entire planet during their reign. Popular culture has painted a picture of dinosaurs inhabiting every possible environment across the globe. However, the reality of dinosaur distribution is far more nuanced and fascinating than a simple story of complete domination. While dinosaurs were indeed one of the most successful vertebrate groups in Earth’s history, spanning approximately 165 million years from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous period, their presence wasn’t universal. This article explores the true extent of dinosaur distribution, examining the environments they conquered, the regions they avoided, and the complex factors that influenced their global spread.

The Geographic Spread of Dinosaurs: A Continental Perspective

Dinosaur fossils have been discovered on every continent, including Antarctica, which might initially suggest they truly were everywhere. However, during the Mesozoic Era (252-66 million years ago), Earth’s continents were arranged differently than today, forming the supercontinent Pangaea that later split into Laurasia and Gondwana. This continental arrangement significantly influenced dinosaur distribution patterns. As landmasses separated, dinosaur populations became isolated, leading to distinct evolutionary paths in different regions. Some dinosaur groups thrived in certain continents while being completely absent in others. For instance, the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex dominated North America but was never present in Africa or South America, where other large theropods like Spinosaurus and Giganotosaurus, respectively, ruled instead.

Environmental Limitations: Where Dinosaurs Didn’t Roam

Despite their adaptability, dinosaurs didn’t inhabit every type of environment available during the Mesozoic. The most obvious exclusion was marine environments—true dinosaurs never evolved to live permanently in the oceans, unlike their relatives, the pterosaurs, who conquered the skies. The oceans during the dinosaur age were instead dominated by marine reptiles like plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and mosasaurs, which were not dinosaurs. Additionally, extremely harsh environments like the highest mountain regions and certain types of deserts likely had limited dinosaur presence. Very cold polar regions, though not as frigid as today’s poles, presented challenges that only specialized dinosaur species could overcome. These environmental limitations created significant “dinosaur-free” zones across the planet throughout their reign.

Polar Dinosaurs: Thriving in Extreme Conditions

One of the most fascinating discoveries in paleontology has been the confirmation that some dinosaurs successfully adapted to polar environments. Fossil evidence from both ancient Arctic and Antarctic regions reveals dinosaur species that lived in these challenging conditions, experiencing months of darkness and relatively cold temperatures. In what is now northern Alaska, paleontologists have discovered remains of duck-billed dinosaurs, horned dinosaurs, and even tyrannosaurs. These polar dinosaurs developed special adaptations, possibly including enhanced vision for low-light conditions and, in some cases, potential seasonal migration patterns. Some species may have even possessed a form of warm-bloodedness or insulating features like primitive feathers to survive colder temperatures. The discovery of polar dinosaurs dramatically changed our understanding of these animals’ adaptability and physiology.

Desert-Dwelling Dinosaurs: Adapting to Arid Landscapes

While extremely harsh deserts may have posed challenges, evidence shows that many dinosaurs successfully adapted to semi-arid and desert environments. The Gobi Desert in Mongolia and parts of the southwestern United States preserve remarkable fossil records of dinosaurs that thrived in relatively dry conditions. These dinosaur species often exhibited specialized adaptations for water conservation and foraging in sparse vegetation landscapes. For instance, some desert-dwelling theropods had more compact bodies and potentially more efficient metabolisms to handle temperature fluctuations. Herbivorous dinosaurs in these regions likely developed specialized digestive systems to process tougher, more fibrous plant material. The discovery of nesting sites in ancient desert environments also suggests that some species specifically selected these areas for reproduction, possibly due to reduced predation or other evolutionary advantages.

The Mystery of Marine Environments: Why Dinosaurs Never Conquered the Seas

Perhaps the most significant limitation in dinosaur distribution was their absence from marine environments. While dinosaurs occasionally ventured into shallow waters and some species like Spinosaurus showed adaptations for semi-aquatic lifestyles, no dinosaur species ever evolved to live permanently in open oceans. This ecological niche was instead filled by various marine reptiles that were not dinosaurs. Scientists have proposed several theories for this limitation, including the specialized hip structure of dinosaurs that may have made fully aquatic adaptations difficult. Additionally, by the time dinosaurs evolved, marine reptile groups were already well-established in oceanic environments, potentially creating competition that blocked dinosaur expansion. This limitation meant that approximately 71% of Earth’s surface—the area covered by oceans—remained largely free from dinosaur presence throughout their entire reign.

Elevation Barriers: Mountain Regions and Dinosaur Distribution

High-elevation environments presented another challenge for dinosaur distribution. While dinosaurs certainly inhabited mountainous regions, extremely high elevations likely had limited dinosaur diversity compared to lowland areas. Reduced oxygen levels, harsh weather conditions, and sparse vegetation in high mountain regions would have created physiological challenges even for these adaptable creatures. Most dinosaur fossils are found in what were once floodplains, deltas, and other lowland environments, suggesting these were their preferred habitats. Some studies suggest that mountain ranges also served as natural barriers that isolated dinosaur populations, contributing to the development of regional species variations. The Appalachian Mountains in North America, for instance, may have created distinct eastern and western dinosaur communities during certain periods of the Mesozoic.

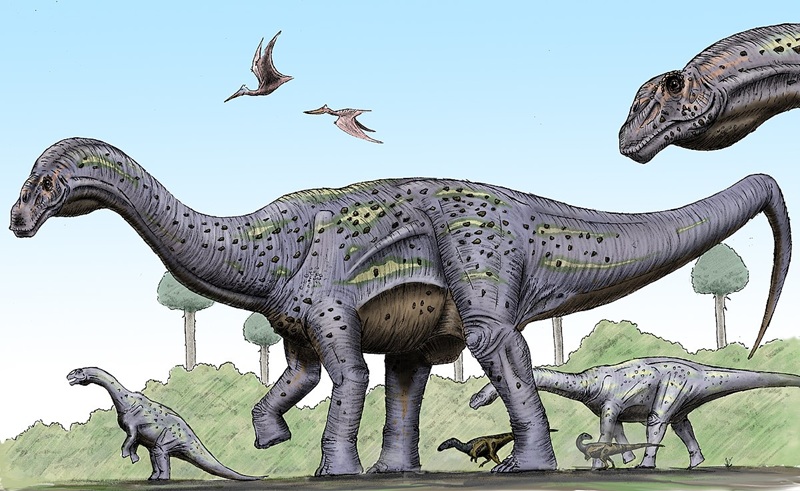

Island Gigantism and Dwarfism: How Isolation Shaped Dinosaur Evolution

As continents broke apart during the Mesozoic Era, some dinosaur populations became isolated on islands, leading to fascinating evolutionary adaptations. Island-dwelling dinosaurs often exhibited either gigantism or dwarfism, depending on resource availability and the absence of certain predators. For example, in what is now Romania, paleontologists have discovered fossils of dwarf sauropods that were significantly smaller than their mainland relatives due to limited resources on their island home. Conversely, some predatory dinosaurs isolated on islands grew larger than their mainland counterparts when facing no competition. These island-specific adaptations created unique dinosaur ecosystems that differed dramatically from mainland environments. This phenomenon demonstrates how geographic isolation significantly influenced dinosaur distribution and evolution, creating distinctive regional variations rather than uniform global dominance.

Biogeographic Patterns: Different Dinosaurs in Different Places

The fossil record clearly shows that dinosaur species weren’t evenly distributed across the planet, even in hospitable environments. Different dinosaur communities evolved in isolation from one another, creating distinct biogeographic regions with their own characteristic species. For instance, during the Late Cretaceous, North America was home to Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops, while contemporaneous African ecosystems featured entirely different predators like Spinosaurus and different herbivores like Ouranosaurus. South America developed its own unique dinosaur fauna, including titanosaurs and the predatory Giganotosaurus. Even within continents, different regions often supported distinct dinosaur communities based on local environments. These biogeographic patterns challenge the notion of uniform global dinosaur dominance, revealing instead a patchwork of specialized dinosaur ecosystems adapted to local conditions.

Freshwater Environments: Riverside and Lakeside Dinosaurs

While dinosaurs never fully conquered marine environments, they successfully exploited freshwater habitats around rivers, lakes, and wetlands. These resource-rich environments became hotspots for dinosaur diversity, as evidenced by the abundance of fossils discovered in ancient riverbed and lakeshore deposits. Some dinosaurs developed specialized adaptations for these environments. The massive Spinosaurus, with its sail-like structure and crocodile-like snout, is now believed to have been semi-aquatic, hunting fish in rivers of North Africa. Other dinosaurs frequented wetlands to feed on abundant vegetation or to prey on other animals drawn to these water sources. These freshwater environments likely served as crucial corridors for dinosaur migration and dispersal across continents, facilitating their spread while still leaving true aquatic environments dinosaur-free.

Climate Fluctuations and Changing Dinosaur Territories

Throughout the Mesozoic Era, Earth experienced significant climate fluctuations that directly impacted dinosaur distribution. During warmer periods, dinosaurs could expand their ranges further toward the poles, while cooling periods might have restricted them to more equatorial regions. Sea level changes dramatically altered coastlines and available habitat, sometimes connecting previously isolated populations or separating others. Evidence suggests that some dinosaur species migrated seasonally to follow food sources or favorable weather conditions, much like many modern animals do today. The late Cretaceous period saw particularly dramatic climate shifts that reshuffled dinosaur communities and likely stressed certain species even before the asteroid impact. These climate-driven distribution changes meant that the map of dinosaur dominance was constantly shifting throughout their long reign.

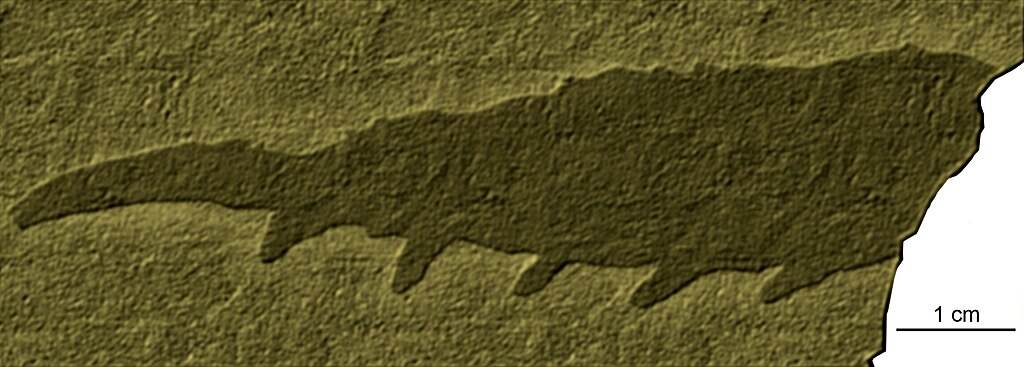

The Shadow of the Small: Microhabitats Beyond Dinosaur Reach

Despite their impressive diversity, dinosaurs couldn’t physically access certain microhabitats due to their size constraints. The smallest dinosaurs were roughly the size of chickens, meaning tiny ecological niches—like small burrows, tree hollows, and other miniature habitats—remained the domain of other animals. These spaces were occupied by mammals, lizards, amphibians, and invertebrates that evolved alongside dinosaurs. The limitations of body size meant that dinosaurs, despite their dominance among large terrestrial vertebrates, represented just one component of much more complex ecosystems. Underground habitats, in particular, remained largely dinosaur-free, providing refuge for small mammals that would later diversify after the dinosaur extinction. This partitioning of habitats by size illustrates another way in which dinosaur dominance, while impressive, was never truly complete across all ecological niches.

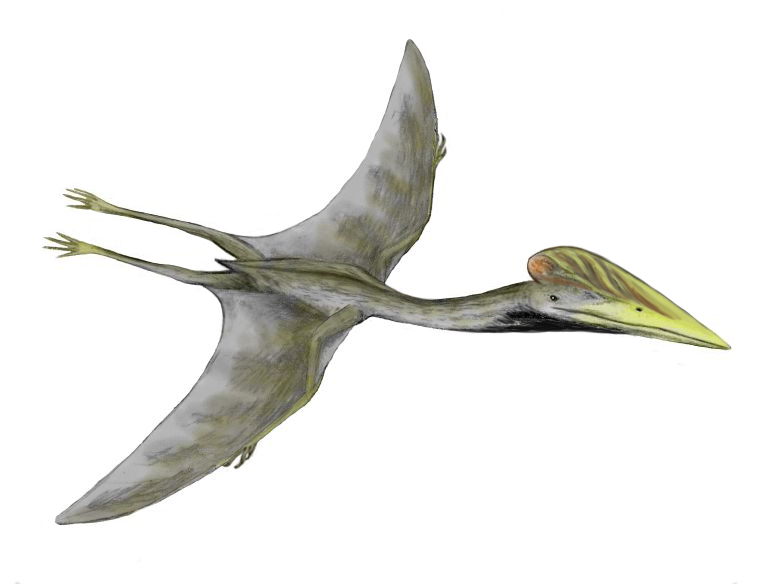

Competition with Other Reptile Groups: Shared Dominance

Dinosaurs weren’t the only successful reptile group during the Mesozoic Era. They shared the planet with several other major reptile lineages that dominated their own ecological niches. Pterosaurs ruled the skies for most of the Mesozoic, evolving a wide range of species from small insectivores to massive filter-feeders with wingspans exceeding 30 feet. In marine environments, plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and later mosasaurs filled the roles of top predators and mid-level consumers. On land, crocodilians competed directly with dinosaurs in many environments, sometimes exceeding them in size and diversity in particular regions. Early in dinosaur evolution, during the Triassic period, several other reptile groups like rhynchosaurs and aetosaurs were also important components of terrestrial ecosystems. This shared dominance reveals that dinosaurs, while tremendously successful, were just one part of a complex reptilian power structure during their era.

The Changing Map of Dinosaur Dominance Through Time

The pattern of dinosaur distribution wasn’t static but changed dramatically over the 165 million years of their existence. Early dinosaurs in the Late Triassic were relatively limited in their distribution and diversity, sharing landscapes with many other reptile groups. The devastating end-Triassic extinction event eliminated many competitors and opened ecological niches for dinosaur expansion. During the Jurassic period, dinosaurs achieved wider distribution, with giant sauropods and various theropods spreading across Pangaea. As continents separated in the Cretaceous period, distinct regional dinosaur faunas developed, creating a patchwork of different dinosaur communities. Some regions like Asia developed extraordinary dinosaur diversity, while other areas maintained more conservative assemblages. The final stages of dinosaur evolution in the Late Cretaceous saw certain groups like hadrosaurs and ceratopsians achieving remarkable diversity in the northern continents, while different communities dominated southern landmasses.

Conclusion: A Nuanced View of Dinosaur Distribution

When we examine the fossil evidence closely, a more complex picture emerges of dinosaur distribution than the simplified narrative of complete global dominance. While dinosaurs unquestionably achieved remarkable evolutionary success and spread across all continents, they never truly occupied every corner of the Earth. Marine environments, extreme habitats, certain microenvironments, and regions with specialized competitors remained beyond their reach. Their distribution was also uneven across time and space, with different dinosaur communities evolving in different regions as continents separated. Rather than seeing this as diminishing their impressive evolutionary story, this nuanced understanding of dinosaur distribution actually enhances our appreciation of these remarkable animals. It reveals dinosaurs as a highly adaptable but still constrained group of organisms that operated within ecological networks alongside many other successful animal lineages. This more accurate picture of dinosaur distribution helps us better understand not just their world, but the biological principles that govern all life on Earth.