When we think of dinosaurs, we often picture these magnificent creatures as static figures frozen in time, but in reality, dinosaurs were dynamic beings with complex behaviors, including extensive migration patterns. Recent paleontological discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur movement across ancient landscapes. By examining fossil evidence, trackways, and applying modern technologies like isotope analysis, scientists are now piecing together the remarkable journeys these prehistoric animals undertook. The question of how far dinosaurs actually migrated opens a fascinating window into their biology, ecology, and the vastly different world they inhabited millions of years ago.

The Evidence for Dinosaur Migration

Paleontologists rely on several lines of evidence to determine if dinosaurs migrated and how far they traveled. Fossil distribution patterns across geographical regions provide initial clues, especially when the same species appears in significantly separated locations. Bone histology—the microscopic study of bone tissue—reveals growth patterns similar to those seen in modern migratory animals. Perhaps most compelling are isotopic analyses of teeth and bones, which can indicate seasonal changes in diet and water consumption consistent with movement between different environments. Additionally, massive dinosaur trackways discovered in places like Wyoming, Colorado, and Australia suggest coordinated group movement over considerable distances, providing tangible evidence of dinosaur herds on the move across ancient landscapes.

Why Dinosaurs Migrated

The motivations behind dinosaur migration likely mirrored those of modern animals. Seasonal food availability would have been a primary driver, pushing dinosaurs to travel as vegetation patterns shifted with changing seasons. Climate avoidance represented another crucial factor, with dinosaurs potentially moving to escape harsh weather conditions in their usual habitats. Breeding requirements may have also influenced migration patterns, with dinosaurs traveling to specific nesting grounds—a behavior observed in many contemporary species. Predator avoidance could have motivated herbivorous dinosaurs to undertake long journeys, creating safety in numbers while moving across landscapes. Together, these factors created complex ecological pressures that shaped dinosaur movement patterns over millions of years of evolution.

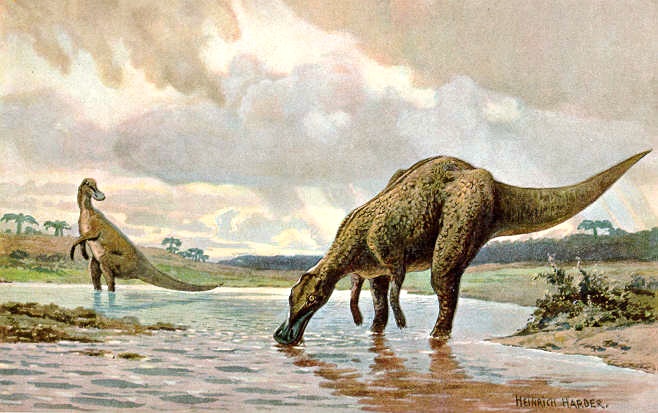

Hadrosaur Migrations: The Duck-Billed Travelers

Hadrosaurs, commonly known as duck-billed dinosaurs, have provided some of the most compelling evidence for extensive dinosaur migration. Studies of Edmontosaurus fossils from the Late Cretaceous period suggest these herbivores migrated seasonally across distances of up to 2,600 kilometers (1,600 miles) in North America. Isotope analysis of their teeth reveals distinct changes in diet that correspond with different geographical regions. Furthermore, massive bone beds containing thousands of hadrosaur specimens indicate these dinosaurs traveled in enormous herds, similar to modern wildebeest or caribou. Their specialized teeth, capable of processing a wide variety of plant materials, made them adaptable to different environments encountered during their extensive journeys across the ancient continent of Laramidia.

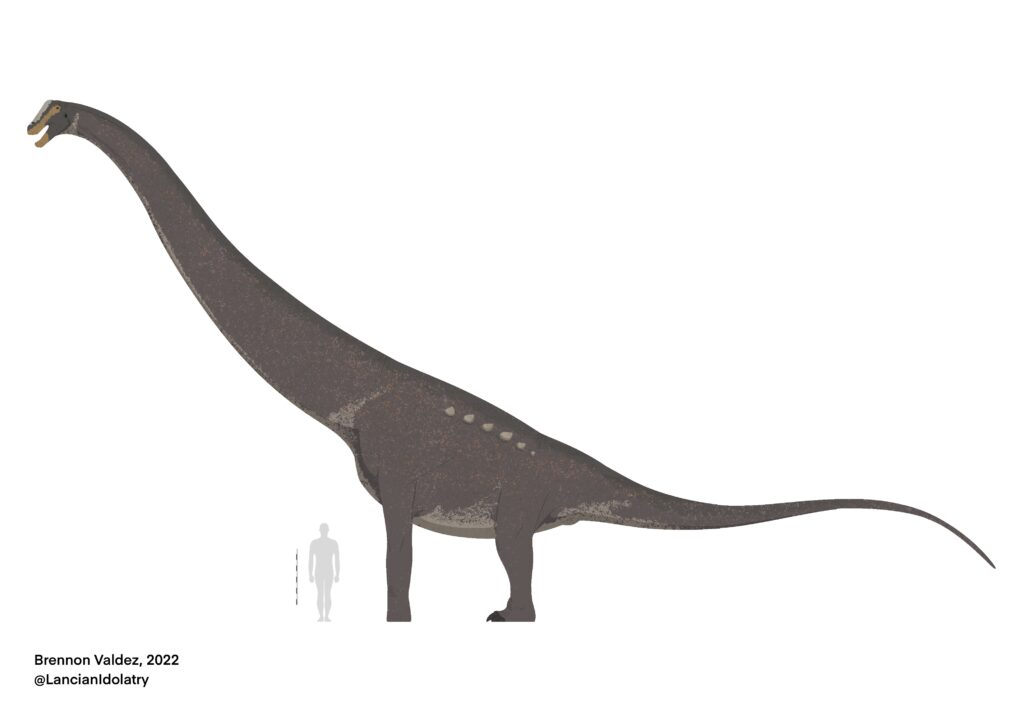

Sauropod Wanderings: Giants on the Move

The largest land animals ever to walk the Earth, sauropods present a fascinating case study in dinosaur movement. Despite their enormous size, evidence suggests some sauropod species undertook significant seasonal migrations. Titanosaur fossils discovered across what is now South America indicate these massive creatures may have traveled hundreds of kilometers annually between feeding grounds. Their distinctive footprint trails, some extending for kilometers, reveal coordinated group movement rather than random wandering. The energy requirements of these giants would have necessitated constant access to abundant vegetation, potentially driving them to follow seasonal growth patterns across vast territories. Interestingly, juvenile and adult footprints found together suggest entire family groups migrated as cohesive units, contrary to earlier theories that only adults undertook these challenging journeys.

Theropod Migration Patterns

Predatory theropods like Tyrannosaurus rex and Allosaurus likely followed different migration patterns than their herbivorous counterparts. Rather than responding directly to vegetation changes, these carnivores would have tracked the movements of their prey species, creating a complex ecological dance across landscapes. Evidence from the famous Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry suggests Allosaurus may have followed seasonal congregations of prey animals, potentially traveling hundreds of kilometers in the process. Isotope studies of Tyrannosaurus teeth indicate these apex predators didn’t stay in one territory for their entire lives but moved across different ecological zones. Smaller theropods like Velociraptor might have undertaken shorter migrations, or in some cases, adapted to survive year-round in a single region by shifting their prey preferences seasonally.

Tracking Ancient Migrations Through Isotope Analysis

Isotope analysis has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur migration by providing chemical signatures that reflect an animal’s environment and diet. When dinosaurs consumed plants or water from different regions, distinctive oxygen, carbon, and strontium isotope ratios became incorporated into their growing teeth and bones. By sampling these tissues in sequential growth layers, scientists can reconstruct migration patterns with remarkable precision. A groundbreaking study of Camarasaurus teeth revealed seasonal movement between lowland and highland environments in the Late Jurassic. Similar analysis of hadrosaur teeth from Alberta, Canada, indicated north-south migrations spanning over 1,000 kilometers annually. This technology continues to advance, allowing paleontologists to map increasingly detailed pictures of dinosaur movements across ancient landscapes.

Continental Drift and Changing Migration Routes

Dinosaur migration patterns evolved dramatically over the Mesozoic Era as the supercontinent Pangaea gradually broke apart into separate landmasses. Early dinosaurs of the Triassic period could potentially range across virtually uninterrupted landscapes spanning what would eventually become separate continents. By the Jurassic period, the initial splitting of Pangaea created new barriers and corridors that reshaped migration possibilities. The Cretaceous period saw further continental fragmentation, with dinosaur populations becoming increasingly isolated on separate landmasses. Rising sea levels during this time created additional challenges, with coastal-dwelling species particularly affected as migration routes were submerged. This dynamic geological context means that migration patterns likely changed significantly over the 165 million years of dinosaur dominance, with species continuously adapting to shifting geographical realities.

Nesting Site Fidelity and Migration

Remarkable fossil discoveries have revealed that many dinosaur species returned to the same nesting grounds year after year, similar to modern sea turtles or certain bird species. The famous “Egg Mountain” site in Montana contains multiple layers of Maiasaura nests built on top of each other over many seasons, suggesting these hadrosaurs migrated back to specific breeding grounds annually. This behavior, known as nesting site fidelity, would have required dinosaurs to undertake predictable seasonal journeys regardless of changing conditions elsewhere. Protoceratops nests found in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert show similar patterns, with multiple generations using the same areas for reproduction. Such dedicated nesting migrations might have covered hundreds or even thousands of kilometers, representing significant investments of energy justified by the benefits of proven, successful breeding locations.

Climate Factors Driving Dinosaur Movement

The Mesozoic Era featured dramatically different climate patterns than our modern world, directly influencing dinosaur migration behaviors. During much of the dinosaur reign, Earth lacked polar ice caps, but still experienced seasonal variations in temperature and precipitation, particularly at higher latitudes. Evidence from plant fossils indicates distinct wet and dry seasons in many dinosaur habitats, creating cyclical patterns of resource availability. Oxygen isotope data from dinosaur teeth suggest some species, particularly larger ones, migrated to avoid temperature extremes that would have challenged their thermoregulatory abilities. The Cretaceous period saw increased seasonality in many regions, potentially driving more extensive migrations. Severe droughts or monsoonal rainfall patterns revealed in sedimentary records would have created additional pressure for dinosaurs to relocate seasonally to maintain access to water and vegetation.

Comparing Dinosaur and Modern Animal Migrations

Modern animal migrations provide useful analogs for understanding dinosaur movement patterns. The annual caribou migration in North America, covering up to 5,000 kilometers round-trip, may resemble the journeys of hadrosaur herds, while elephant movements in response to seasonal resources might parallel sauropod behaviors. Bird migrations offer particularly valuable comparisons, as birds are direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs and may have inherited some migratory instincts from their distant ancestors. African wildebeest, which follow rainfall patterns across the Serengeti in herds of millions, demonstrate how large herbivores can coordinate massive migrations—a pattern potentially mirrored by ceratopsians and other herbivorous dinosaurs. These modern analogs help scientists develop models for understanding the scale, timing, and ecological significance of dinosaur migrations in prehistoric ecosystems.

Physiological Adaptations for Long-Distance Travel

Dinosaurs possessed numerous adaptations that facilitated their migratory lifestyles. Their efficient respiratory systems, featuring air sacs similar to those in modern birds, would have provided the high oxygen uptake necessary for sustained travel. Leg proportions in many migratory species show adaptations for efficient locomotion, with hadrosaurs and certain theropods exhibiting limb designs optimized for covering long distances with minimal energy expenditure. Cardiovascular adaptations, though not directly preserved in fossils, can be inferred from bone structures that would have supported powerful heart and lung capacities. Additionally, many migratory dinosaur species show evidence of significant fat storage capabilities, critical for fueling long journeys through potentially resource-scarce territories. These physiological specializations evolved over millions of years, gradually optimizing dinosaurs for the remarkable journeys they undertook across ancient landscapes.

Barriers to Dinosaur Migration

Despite their impressive mobility, dinosaurs faced significant barriers that shaped and limited their migration routes. Mountain ranges posed formidable obstacles, particularly for larger species, though fossil evidence suggests some dinosaurs utilized mountain passes as migration corridors. Ancient seas and large rivers created boundaries that could only be circumnavigated, sometimes adding hundreds of kilometers to migration journeys. Dense forests may have impeded the movement of larger dinosaurs, particularly sauropods, channeling them through more open terrain. Climate barriers such as deserts or semi-arid regions would have been particularly challenging, requiring specialized adaptations or careful timing to traverse safely. These geographical constraints created natural migration corridors that concentrated dinosaur movements along predictable routes, potentially explaining the formation of massive fossil bonebeds at certain chokepoints where natural disasters could claim entire herds.

The Future of Dinosaur Migration Research

The study of dinosaur migration represents one of paleontology’s most dynamic and rapidly evolving fields. Advanced technologies continue to transform our understanding, with micro-CT scanning revealing previously undetectable growth patterns in fossil bones that indicate seasonal movement. Drone-based photogrammetry has revolutionized the study of dinosaur trackways, allowing researchers to map extensive migration routes across challenging terrain. Sophisticated computer modeling now integrates climate data, plant distributions, and dinosaur physiological requirements to predict likely migration patterns. DNA preservation in exceptionally well-preserved fossils, though still rare, may eventually reveal genetic adaptations for migratory behavior. As these technologies continue to develop and new fossil discoveries emerge from previously unexplored regions, our understanding of dinosaur migration will become increasingly sophisticated, revealing the complex movements of these magnificent animals across the ancient Earth.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Lives of Prehistoric Travelers

The emerging picture of dinosaur migration reveals these animals not as static monuments but as dynamic creatures constantly on the move across changing landscapes. From the massive sauropods traversing hundreds of kilometers between seasonal feeding grounds to hadrosaur herds making annual journeys spanning thousands of kilometers, dinosaurs were true travelers of their ancient world. Their migrations represented complex ecological adaptations, responses to the rhythms of seasons and resources that shaped their evolution over millions of years. As research techniques continue to advance, we can expect even more detailed insights into the remarkable journeys these animals undertook. Understanding dinosaur migration not only illuminates a fascinating aspect of prehistoric life but also provides valuable context for comprehending how modern animals respond to changing environments—a perspective increasingly relevant in our era of rapid climate change and habitat transformation.