Imagine peeling back the pages of the world’s oldest storybook, one written not in ink but in fossilized scales, hollow spikes, and feathery filaments preserved for hundreds of millions of years. Every fragment of dinosaur skin scientists uncover is a chapter, a stunning reveal about how these ancient creatures survived, communicated, and evolved under conditions that would challenge even our most extreme modern environments.

You might think we already know everything there is to know about dinosaurs. But honestly, each new fossil discovery rewrites what we thought was a closed book. From silica-preserved skin glowing orange under ultraviolet light to hollow porcupine-like spikes never seen before in any known species, the study of dinosaur integument – fancy science-talk for external body coverings – is one of the most electrifying frontiers in paleontology. Let’s dive in.

The Rarest Treasure in Paleontology: Preserved Soft Tissue

Walk through any natural history museum and you will notice something immediately. It is almost all bones. That is not laziness on the part of museum curators – it is simply the reality of fossilization. The majority of fossils we see in museums are skeletons, and the reason is pretty simple: bones don’t decompose very quickly, so they have more time to fossilize. Soft tissues like skin, muscle and organs usually rot away or are eaten by scavengers soon after death. Skin, in particular, requires a near-miraculous set of conditions to survive millions of years.

Soft tissues decompose quickly, making preservation exceptionally challenging. Only unique conditions – like rapid burial and mineral-rich environments – allow such fossils to form. Think of it like trying to press a wet paper towel between two rocks and hoping it survives a geological era. The odds are staggering, which makes every preserved skin specimen an almost unbelievable scientific gift.

The World’s Oldest Known Skin: A 286-Million-Year-Old Revelation

Here is something that might genuinely make you stop and stare at the ceiling for a moment. Scientists have discovered the oldest known skin fossils, dating back long before the dinosaurs. The samples, found in a cave in Oklahoma, USA, show that reptile scales haven’t changed much in the last 286 million years. That is an almost incomprehensible span of biological consistency. Your phone becomes obsolete in two years, yet a scale pattern persisted for nearly three hundred million.

In this case, the skin itself is preserved in a series of small, three-dimensional fragments, including the tough outer epidermis layer and the rarer, inner dermis layer. The fossils were discovered in Richards Spur, a limestone cave system in Oklahoma, by fossil hunters Bill and Julie May. It’s the oldest example of preserved epidermis, the outermost layer of skin in terrestrial reptiles, birds, and mammals, which was an important evolutionary adaptation in the transition to life on land. That single fact alone reframes what we understand about ancient land life.

A Dinosaur With Glass-Like Skin: The Hidden Gem of Nanjing

Palaeontologists at University College Cork in Ireland discovered that some feathered dinosaurs had scaly skin like reptiles today, shedding new light on the evolutionary transition from scales to feathers. The researchers studied a new specimen of the feathered dinosaur Psittacosaurus from the early Cretaceous, a time when dinosaurs were evolving into birds. What they found hidden within that fossil, though, was the genuinely jaw-dropping part.

The team used ultraviolet light to identify patches of preserved skin, which are invisible in natural light. Further investigation of the fossil skin using X-rays and infrared light revealed spectacular details of preserved cellular structure. Even more astonishing, what is really surprising is the chemistry of the fossil skin – it is composed of silica, the same as glass. This type of preservation has never been found in vertebrate fossils. Skin turned to glass. You honestly couldn’t write that into a science-fiction story without someone calling it too far-fetched.

Scales and Feathers at the Same Time: The “Zoned Development” Discovery

One of the most fascinating recent breakthroughs is the idea that dinosaurs didn’t just transition cleanly from scales to feathers. It was messier than that – and far more interesting. Palaeontologists at University College Cork in Ireland discovered that some feathered dinosaurs had scaly skin like reptiles today, shedding new light on the evolutionary transition from scales to feathers. The discovery revealed a kind of evolutionary compromise happening right there in the fossil record.

The fossil evidence supports partitioning of skin development in Psittacosaurus: a reptile-type condition in non-feathered regions and an avian-like condition in feathered regions. Retention of reptile-type skin in non-feathered regions would have ensured essential skin functions during the early, experimental stages of feather evolution. Think of it like upgrading only part of your wardrobe at a time – you keep the reliable old jacket while you test out the new gear. This zoned development would have maintained essential skin functions, such as protection against abrasion, dehydration and parasites.

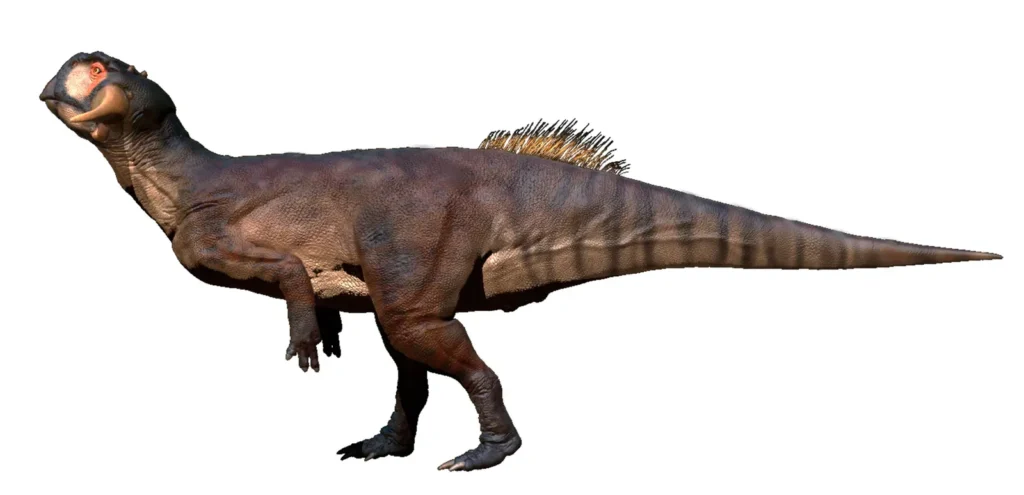

Hollow Spikes and a Brand-New Dinosaur: The 2026 Sensation

Just in early 2026, science dropped a discovery that genuinely rewrote the dinosaur textbook all over again. A 125-million-year-old dinosaur just rewrote what we thought we knew about prehistoric life. Scientists in China uncovered an exceptionally preserved juvenile iguanodontian with fossilized skin so detailed that individual cells are still visible. Even more astonishing, the plant-eating dinosaur was covered in hollow, porcupine-like spikes – structures never before documented in any dinosaur.

The hollow spikes may have served as a defensive adaptation, functioning in a way similar to the quills of a porcupine by discouraging predators from attacking. However, defense may not have been their only purpose. Researchers suggest the spikes could also have helped regulate body temperature, a process known as thermoregulation. Another possibility is that the spikes had a sensory role, helping the dinosaur detect movement or environmental changes around it. One small fossil with so many enormous implications – that, to me, is science at its most thrilling.

Feathers Were Not Originally Built for Flight

Let’s be real for a second: when most people think of feathers, they think of flying. It’s the obvious connection. But the fossil evidence tells a far more nuanced story. Most famously, feathers allowed early birds and related dinosaurs like Microraptor to take to the air. But paleontologists have also found feathers and related structures on many other dinosaurs that never would have flapped into the air, like the 30-foot-long Yutyrannus. Among these flightless dinosaurs, plumage had a variety of other functions – from keeping warm to camouflage.

It has been suggested that feathers had originally functioned as thermal insulation, as it remains their function in the down feathers of infant birds prior to their eventual modification into structures that support flight. Many dinosaurs appear to have had filamentous coverings resembling fuzzy down rather than the aerodynamic feathers seen on flying birds. These proto-feathers lacked vanes and interlocking barbs but shared the same basic protein composition and growth patterns. Over millions of years, these simple filaments diversified into more complex structures, eventually enabling powered flight in birds. Flight, it seems, came along for the ride much later.

Color, Camouflage, and Communication Written in Ancient Scales

Here’s the thing most people don’t realize: scientists can actually reconstruct what color some dinosaurs were. Not through guesswork, but through microscopic analysis of preserved pigment structures. Scales can reveal dinosaur coloration. First established by comparing the microscopic details of dinosaur feathers to those of modern birds, paleontologists have been able to reconstruct the hues ancient dinosaurs were. The same principles hold for exceptionally preserved scales.

A 2016 study of the dinosaur Psittacosaurus’s skin found that it had darker scales above and lighter scales beneath. This form of camouflage is known as countershading. If spotted from above, the dark colors on the dinosaur’s back would have helped it blend in with the forest habitat. A study of the spiky, armored dinosaur Borealopelta published the following year found a similar pattern. The dinosaur was reddish above and lighter below, which would have helped it hide from tyrannosaurs in the ancient forest. Nature has always been the most ruthless designer – and these dinosaurs wore their survival strategy right on their skin.

The Dinosaur Mummy That Changed Everything We Know About Skin

In late 2025, researchers revealed something extraordinary about the duck-billed dinosaur Edmontosaurus that stunned even veteran paleontologists. A thin layer of clay over the fossilized skeleton of the juvenile Edmontosaurus preserved large areas of scaly, wrinkled skin and a fleshy crest over its back. This wasn’t just another skin impression. This was a complete biological portrait, millions of years in the making.

According to analyses, the dinosaur, which could grow to over 12 meters long, had a fleshy crest along the neck and back and a row of spikes running down the tail. The creature’s skin was thin enough to produce delicate wrinkles over the rib cage and was dotted with small, pebble-like scales. Shockingly, the clay mask revealed that the animal had hooves, a trait previously preserved only in mammals. That makes it the oldest land animal proven to have hooves and the first known example of a hooved reptile. Dinosaurs with hooves. I know it sounds crazy, but there you have it.

Conclusion: Every Fossil Skin Is a Letter From Deep Time

What these discoveries collectively reveal is that dinosaur skin and feathers were never simple, passive features. They were active, evolving, multi-purpose tools for survival – shields against predators, temperature regulators, communication signals, and eventually the scaffolding for flight itself. The picture that emerges from the fossil record is one of breathtaking biological creativity stretched across hundreds of millions of years.

You might look at a museum skeleton and see something static and ancient. But behind every bone, there was once a living surface – scaled, feathered, spiked, or mottled with camouflage – that told the world exactly who that animal was and how it intended to survive. The more scientists look, the more that surface comes back to life. Whether fuzz was an early, common dinosaur trait or appeared multiple times, certainly many more feathered dinosaur species are left to be uncovered. With every season that paleontologists return to the world’s Mesozoic rocks, the menagerie of feathery dinosaurs is only set to grow.

The story of dinosaur skin and feathers is ultimately our story too – a reminder that adaptation is survival, and survival is endlessly inventive. What feature of dinosaur evolution surprises you the most? Tell us in the comments below.