The 19th century marked a pivotal era in our understanding of prehistoric life, as paleontological discoveries transformed enigmatic fossils into recognizable creatures from Earth’s distant past. As scientists unearthed and assembled dinosaur remains, these ancient reptiles simultaneously captured the public imagination through literature. The emerging scientific field of paleontology and the flowering of Victorian literature created a unique intersection where dinosaurs transitioned from scientific specimens to narrative characters. This article explores how 19th-century literature incorporated, interpreted, and sometimes misrepresented dinosaurs, reflecting both the scientific understanding of the time and broader cultural anxieties about evolution, extinction, and humanity’s place in natural history.

The Dawn of Paleontology and Literary Imagination

Before dinosaurs could populate literature, they needed to be discovered and named by science. The term “dinosaur,” meaning “terrible lizard,” was coined by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, creating a taxonomic category for the strange fossils being unearthed across Europe and America. This scientific categorization provided writers with a new vocabulary and conceptual framework. Early literary references to dinosaurs often appeared in scientific journals and popular science writing, where authors attempted to convey the wonder of these discoveries to a public still grappling with the idea that entire species could vanish from Earth. Writers like Charles Dickens incorporated references to geological time and extinct creatures in works such as “Bleak House” (1853), demonstrating how quickly dinosaur science permeated literary consciousness. The tension between religious explanations for fossils and emerging scientific theories created a fertile ground for writers to explore larger questions about creation and extinction.

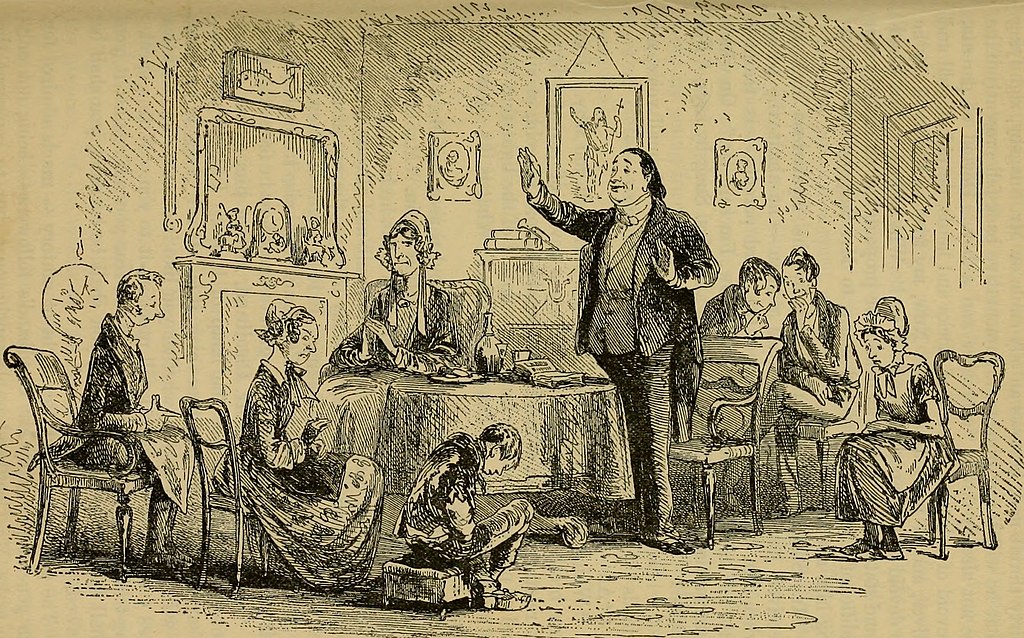

Charles Dickens and the Megalosaurus

One of the earliest and most famous literary references to a dinosaur appears in the opening paragraph of Charles Dickens’ novel “Bleak House” (1853). Dickens evokes a primordial atmosphere for fog-bound London by writing: “Implacable November weather… with a dinosaur wandering like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.” Specifically, he mentions a Megalosaurus “forty feet long or so,” creating an unforgettable image that merges ancient prehistory with Victorian London. This casual reference indicates how dinosaurs had already entered the cultural vernacular, becoming useful metaphors even in works not explicitly about prehistory. Dickens uses the dinosaur not merely as decoration but as a symbol of primeval forces persisting into the modern age. The Megalosaurus serves as a striking reminder of geological time scales against which human concerns might seem trivial, while simultaneously heightening the novel’s critique of antiquated social institutions.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s “The Coming Race”

Published in 1871, Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s “The Coming Race” presents one of the 19th century’s most fascinating literary engagements with prehistoric life. This science fiction novel describes an advanced subterranean civilization and their encounters with prehistoric creatures preserved in underground ecosystems. Although not explicitly labeling them as dinosaurs, Bulwer-Lytton describes reptilian creatures clearly inspired by contemporary paleontological discoveries. The novel reflects Victorian anxieties about evolution and degeneration, using dinosaur-like creatures as symbols of primordial savagery against which human advancement could be measured. “The Coming Race” also introduced the concept of prehistoric creatures surviving in isolated environments, a trope that would become extremely influential in later adventure fiction. Bulwer-Lytton’s work demonstrates how dinosaurs were becoming useful fictional devices for exploring evolutionary theory, which was still controversial in the years following Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” (1859).

Jules Verne and the Hollow Earth Theory

Jules Verne’s “Journey to the Center of the Earth” (1864) stands as perhaps the most influential 19th-century fictional work featuring prehistoric creatures. While Verne did not limit himself to dinosaurs, including various prehistoric mammals and marine reptiles, his novel popularized the concept of living prehistoric animals surviving in Earth’s interior. The protagonists encounter an ichthyosaur and a plesiosaur engaged in battle, a scene directly inspired by contemporary paleontological reconstructions and discussions. Verne consulted scientific literature of his time, incorporating actual fossil discoveries and taxonomic names to lend credibility to his fantastic journey. The novel exemplifies how scientific knowledge could be transformed into an adventure narrative, with dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures serving as both scientific curiosities and sources of narrative tension. Verne’s approach to prehistoric life balanced scientific accuracy with speculation, creating a model for science fiction that would influence generations of writers.

Charles Kingsley’s “The Water-Babies”

Charles Kingsley’s children’s novel “The Water-Babies” (1863) represents an interesting case of dinosaurs appearing in didactic literature aimed at young readers. While primarily a moral fairy tale, the book includes discussions of extinction and prehistoric life as part of its educational content. Kingsley, who was both a clergyman and an advocate for natural science, used references to prehistoric creatures to introduce children to contemporary scientific discoveries. He attempted to reconcile religious and scientific worldviews at a time when many saw them as incompatible. Rather than portraying dinosaurs as monsters, Kingsley presents extinct creatures as part of God’s grand natural plan, demonstrating how some Victorian authors integrated prehistoric life into religious frameworks. This approach made dinosaurs acceptable subject matter for children’s literature and helped normalize evolutionary concepts for young readers, marking an important step in dinosaurs’ journey from scientific specimens to cultural icons.

Scientific Accuracy and Artistic License

The scientific understanding of dinosaurs evolved significantly throughout the 19th century, and literature reflected these shifting conceptions. Early literary depictions often presented dinosaurs as giant lizards or crocodile-like creatures, consistent with initial scientific interpretations. As paleontological knowledge advanced, particularly after Owen’s work on dinosaur posture and anatomy, some authors updated their portrayals accordingly. However, many writers prioritized dramatic effect over scientific accuracy, perpetuating outdated views of dinosaurs as sluggish, cold-blooded reptiles. The tension between scientific accuracy and narrative requirements created dinosaur depictions that were often hybrids of fact and fantasy. Illustrators working with authors frequently emphasized the monstrous aspects of dinosaurs, exaggerating features to heighten reader excitement. This pattern established a tradition of dinosaurs in fiction being simultaneously based on science yet departing from it when narratively convenient—a practice that continues in dinosaur fiction to this day.

The Great Exhibition and Public Consciousness

The Crystal Palace dinosaur models, unveiled in 1854 as part of the relocation of the Great Exhibition structures to Sydenham, represented a crucial moment in public dinosaur awareness that directly influenced literature. These life-sized concrete sculptures, created under Owen’s scientific direction, were the first public three-dimensional representations of dinosaurs ever displayed. Though now known to be anatomically incorrect in many respects, they were groundbreaking in translating paleontological knowledge into tangible form. Writers visiting the exhibition incorporated these visual impressions into their work, often referencing the Crystal Palace dinosaurs directly or borrowing from their distinctive appearance. The sculptures effectively standardized the public image of dinosaurs for a generation, creating a common visual vocabulary that authors could reference when including dinosaurs in their writings. This exhibition marked the beginning of dinosaurs as public spectacle, establishing a pattern of popular fascination that would fuel both scientific research and literary imagination.

Lost Worlds and Prehistoric Survivors

By the late 19th century, a distinct literary subgenre emerged featuring “lost worlds” where prehistoric creatures survived into modern times. While Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Lost World” (1912) falls just outside our period, its antecedents appeared in numerous 19th-century works. These narratives typically featured isolated geographical regions—remote plateaus, underground caverns, or uncharted islands—where dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures continued to thrive. Such stories reconciled the scientific fact of dinosaur extinction with the narrative desire for living, breathing dinosaur characters. This trope allowed writers to bring contemporary human characters face-to-face with prehistoric life, creating dramatic confrontations between modern and ancient worlds. The lost world genre also reflected imperial exploration narratives, as Western protagonists “discovered” these prehistoric enclaves much as they were exploring the globe’s remaining uncharted regions. These stories established dinosaurs as symbols of untamed wilderness and primordial nature, contrasted with modern civilization and technology.

Dinosaurs as Moral and Political Metaphors

Beyond their role as scientific curiosities or adventure story antagonists, dinosaurs served as powerful metaphors in 19th-century literature. Their massive size yet ultimate extinction made them perfect symbols for various philosophical and political points. Some conservative writers invoked dinosaurs as cautionary tales about the dangers of failing to adapt, using them to argue against social reform. Conversely, progressive authors pointed to dinosaur extinction as evidence that even the mightiest can fall, suggesting that current power structures were not immutable. Religious writers interpreted dinosaurs within biblical frameworks, with some suggesting they were antediluvian creatures that perished in Noah’s flood. The seemingly sudden disappearance of such dominant creatures provoked questions about divine intervention versus natural processes in shaping Earth’s history. These metaphorical uses reveal how dinosaurs became integrated into broader cultural discourses about progress, power, and the nature of historical change.

Rudyard Kipling’s “How the Whale Got His Throat”

Rudyard Kipling’s “Just So Stories” (1902) includes several tales referencing prehistoric times, though only obliquely mentioning dinosaurs specifically. However, these stories represent an important development in dinosaur literature—the transformation of scientific knowledge into mythology and folklore. Kipling created whimsical origin stories for modern animals that playfully incorporated evolutionary concepts in child-friendly formats. Though not scientifically accurate, these stories helped normalize the concept of prehistoric life and evolutionary change for young readers. By framing prehistory in terms of familiar folklore structures, Kipling made the distant past accessible and entertaining. His approach demonstrates how dinosaurs were transitioning from purely scientific subjects to cultural touchstones with narrative potential. This transformation would accelerate in the early 20th century, but Kipling’s work shows the process already underway in late Victorian children’s literature, making dinosaurs part of an imaginative rather than strictly scientific realm.

Natural History Museums and Literary Imagination

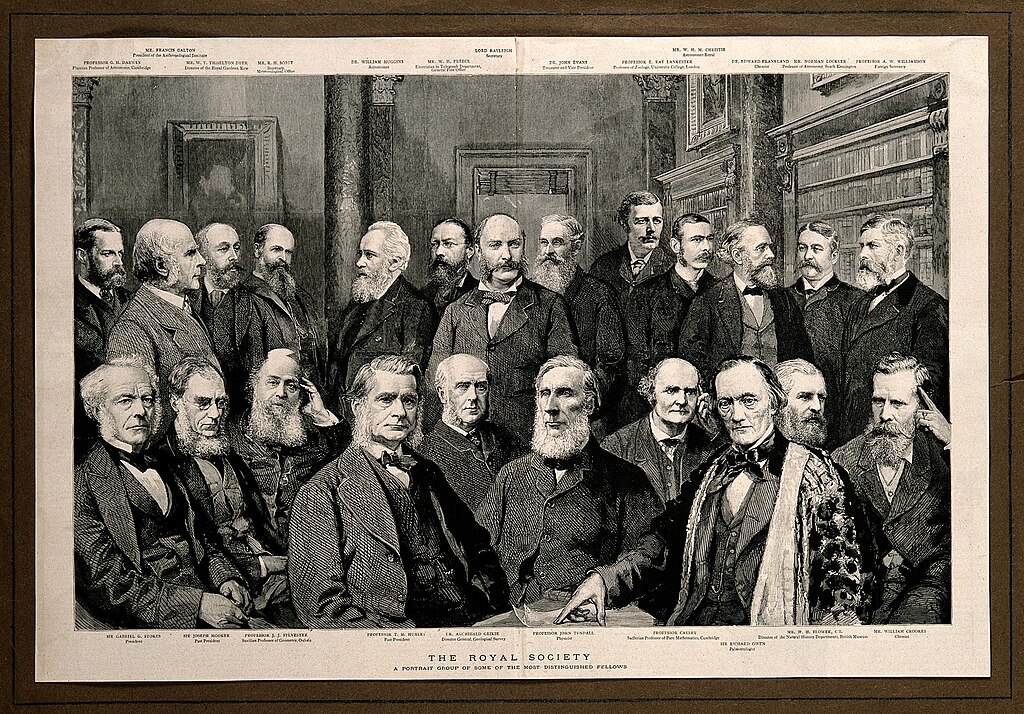

The establishment and expansion of natural history museums throughout the 19th century created physical spaces where the public could encounter dinosaur fossils and reconstructions, directly influencing literary descriptions. Many authors explicitly mentioned visiting museum exhibitions before writing about prehistoric creatures, grounding their fictional accounts in these tangible encounters. Museums like the British Museum of Natural History (now the Natural History Museum) in London and the American Museum of Natural History in New York became important cultural institutions where science and imagination intersected. Museum displays, with their dramatic skeletal mounts and painted backdrops, suggested narrative scenarios that writers could expand upon in fiction. The theatrical aspects of these exhibitions, often emphasizing the monstrous and spectacular aspects of dinosaurs, reinforced their potential as literary subjects. Museum guidebooks and popular science presentations associated with these institutions also provided writers with accessible scientific information they could incorporate into their work.

The Dinosaur Renaissance of the 1880s-1890s

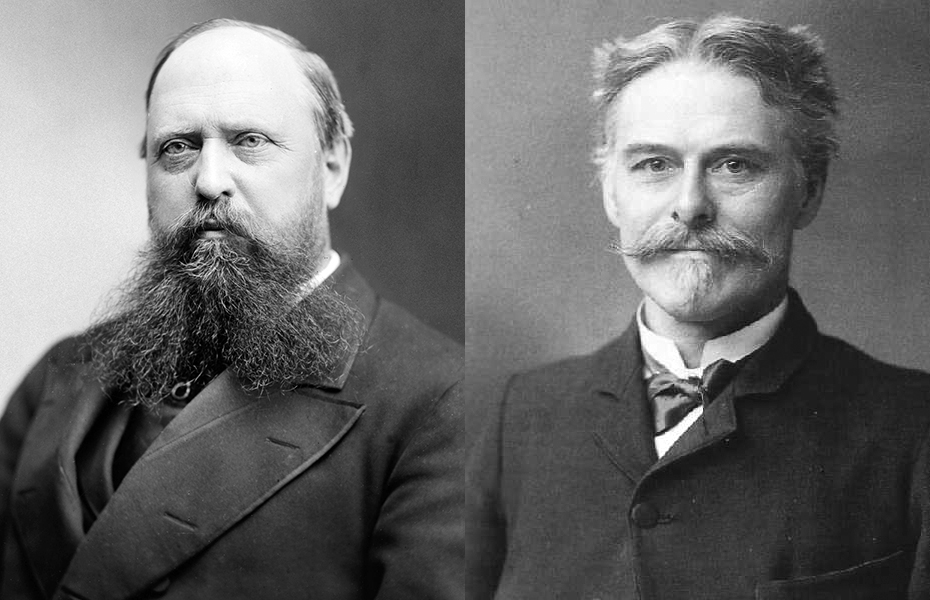

The last decades of the 19th century witnessed what might be called the first “dinosaur renaissance,” as spectacular new discoveries in the American West dramatically expanded scientific understanding. Paleontologists like Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope engaged in the famous “Bone Wars,” a competitive rush to discover and name new dinosaur species. These discoveries, widely reported in both scientific journals and popular press, fueled public fascination and provided writers with an expanded roster of dinosaur species to incorporate into fiction. The strange features of newly discovered dinosaurs like Stegosaurus and Triceratops, with their elaborate plates and horns, inspired writers to create more diverse and fantastic prehistoric scenarios. Literary works from this period reflect this explosion of new paleontological knowledge, with more specific and varied dinosaur references appearing in fiction across genres. This scientific renaissance laid the groundwork for the dinosaur fiction boom that would follow in the early 20th century with works like Doyle’s “The Lost World.”

The Legacy of 19th-Century Dinosaur Literature

The literary treatment of dinosaurs in the 19th century established patterns and tropes that would influence depictions for generations to come. The century saw dinosaurs transform from barely understood scientific curiosities to versatile literary symbols and characters, a journey that paralleled their scientific reconstruction from scattered fossils to recognizable creatures. The major narrative frameworks established during this period—dinosaurs as monsters, as evolutionary lessons, as survivors in lost worlds, and as metaphors for power and obsolescence—remain fundamental to dinosaur fiction today. Early authors working without established conventions had to decide how to integrate these creatures into narrative, creating approaches that later writers would refine rather than reinvent. The tension between scientific accuracy and dramatic storytelling, already evident in 19th-century works, continues to characterize dinosaur fiction in all media. By establishing dinosaurs as legitimate subjects for literary imagination, 19th-century authors helped ensure these creatures would remain cultural icons long after their physical extinction.

As we look back on these early literary encounters with dinosaurs, we can see how they reflected the intellectual currents and cultural concerns of their time. The transformation of dinosaurs from scientific specimens to story characters parallels broader Victorian negotiations between science and imagination, reason and wonder. These works remind us that dinosaurs have always existed in two realms simultaneously: as subjects of scientific inquiry and as creatures of narrative. This dual existence, established in the 19th century, explains their enduring appeal across disciplines and audiences. The dinosaurs that captured Victorian imaginations may differ from those we envision today, but the fascination they inspired continues undiminished, a testament to their power as symbols of a world both scientifically knowable and perpetually beyond human experience.