Dinosaurs have captivated human imagination since the first fossils were scientifically described in the early 19th century. From museum exhibits to blockbuster movies, we’ve all seen vivid depictions of these prehistoric creatures. But how accurate are these representations? The science of reconstructing dinosaur appearances has evolved dramatically over the decades, with new discoveries constantly challenging our understanding. This article explores the fascinating journey of dinosaur visualization, the evidence scientists use, the limitations they face, and how our perception of these ancient reptiles continues to change with advancing research techniques.

The Fossil Record: An Incomplete Puzzle

The primary challenge in reconstructing dinosaur appearances lies in the incompleteness of the fossil record. Fossilization is an exceptionally rare process, requiring specific conditions that preserve only a tiny fraction of prehistoric life. Most dinosaur species are known from partial skeletons, with many represented by just a few bones or teeth. Even the most complete specimens typically lack soft tissues like skin, muscles, and internal organs. This incompleteness forces paleontologists to make educated guesses about many aspects of dinosaur anatomy, using comparative studies with living relatives and anatomical principles. The fragmentary nature of the evidence means that our visualizations are necessarily speculative to some degree, representing scientists’ best interpretations based on available data rather than definitive portraits.

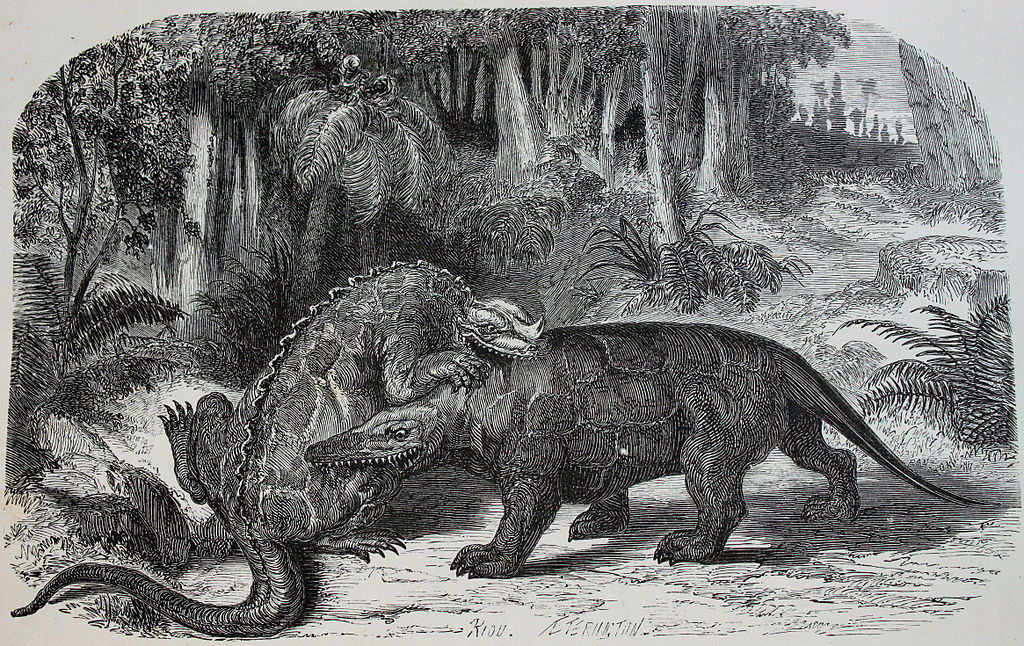

The Evolution of Dinosaur Depictions

Dinosaur imagery has undergone dramatic transformations since the Victorian era. The earliest reconstructions portrayed dinosaurs as lumbering, reptilian creatures—essentially oversized lizards with sprawling limbs. This interpretation reflected the limited understanding of the time and biases toward familiar modern reptiles. The “Dinosaur Renaissance” of the 1960s and 1970s, spearheaded by paleontologists like Robert Bakker and John Ostrom, revolutionized our view by presenting dinosaurs as active, possibly warm-blooded animals with upright postures. By the 1990s, evidence for feathered dinosaurs began emerging from China, forcing another major revision in dinosaur imagery. Each era’s depictions reveal as much about the scientific understanding and cultural context of their time as they do about the dinosaurs themselves. Today’s reconstructions continue this evolution, incorporating the latest research on posture, movement, and integumentary structures.

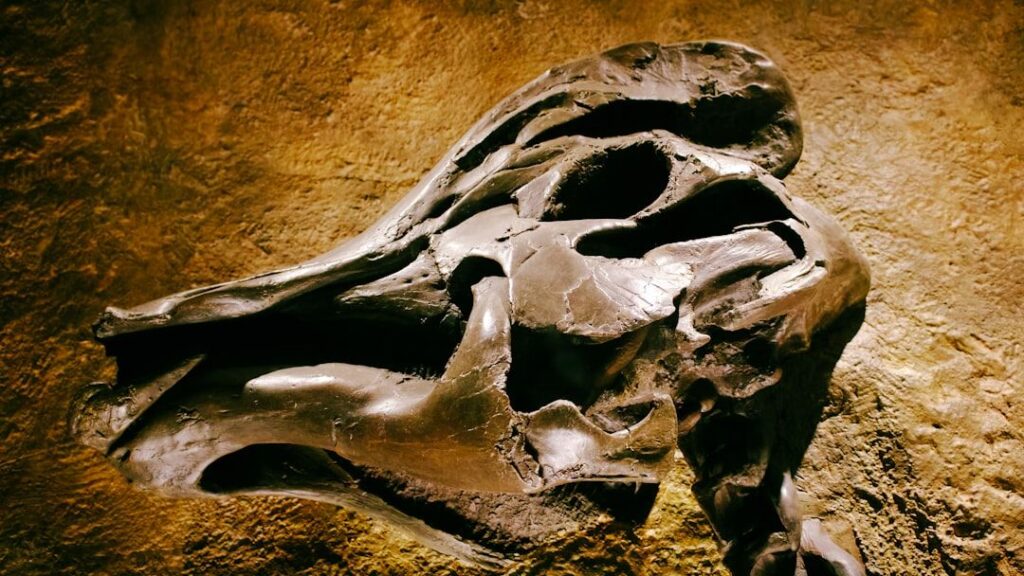

Skin Impressions: Rare Windows into Dinosaur Covering

While exceptionally rare, fossilized skin impressions provide crucial direct evidence of dinosaur external appearance. These impressions form when a dinosaur’s skin comes into contact with fine sediment that preserves its texture before decay. Notable examples include specimens of hadrosaurs and ceratopsians with extensive skin impressions showing varied scale patterns and textures. The “mummy” dinosaur Edmontosaurus, discovered in Wyoming, preserved detailed skin impressions across large portions of its body, revealing a complex arrangement of scales unlike anything in modern reptiles. Skin impressions from Carnotaurus, a predatory abelisaurid, show a striking pattern of non-overlapping scales with larger feature scales arranged in rows. These fossils demonstrate that dinosaur skin was not simply like that of modern lizards or crocodiles, but displayed unique specializations and diversity across different dinosaur groups. However, skin impressions remain extremely uncommon, leaving most species without direct evidence of their external covering.

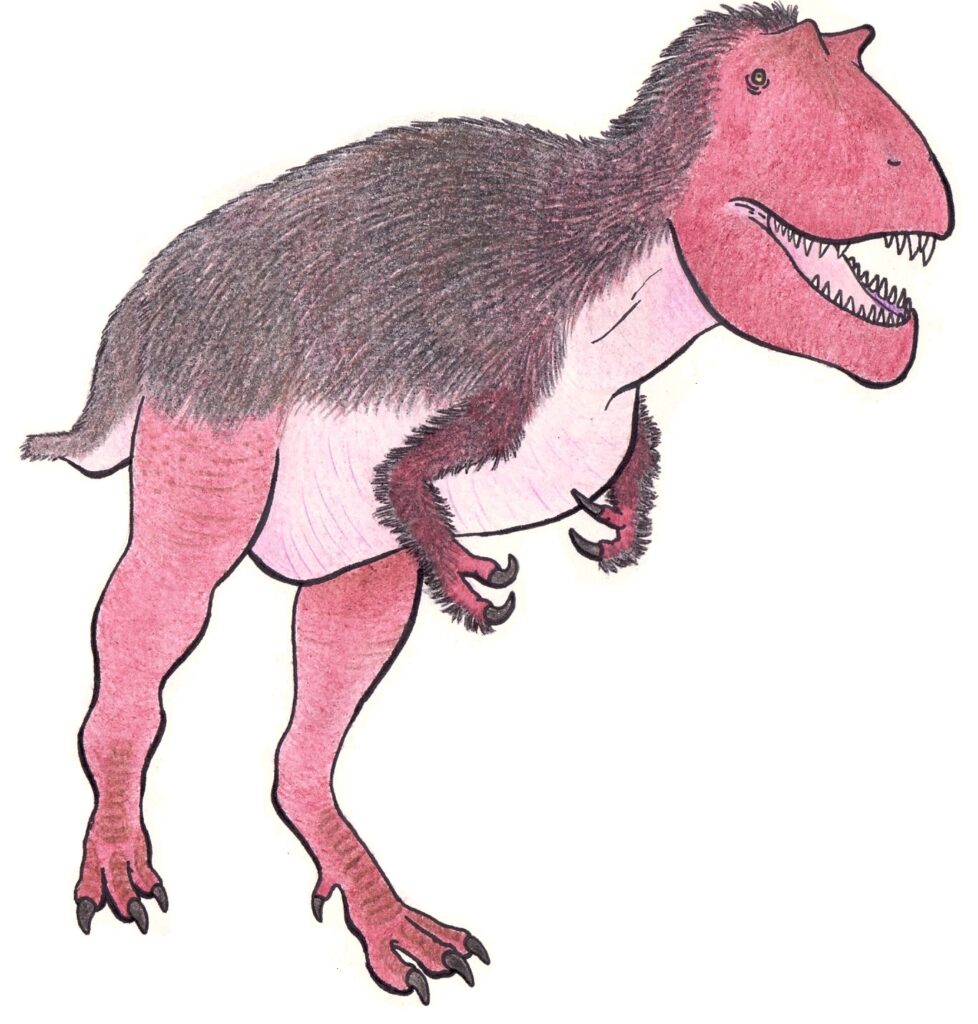

The Feather Revolution

Perhaps the most dramatic shift in dinosaur visualization came with the discovery of feathered dinosaurs from the Liaoning Province in China beginning in the 1990s. These exquisitely preserved fossils revealed that many theropod dinosaurs—including close relatives of Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus—possessed feathers or feather-like structures. The implications were revolutionary, establishing a direct evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and birds. Specimens like Sinosauropteryx showed primitive filamentous feathers, while Microraptor preserved complex, aerodynamic feather arrangements on all four limbs. These discoveries have forced a complete rethinking of dinosaur appearance, especially for theropods. The evidence suggests feathers or feather-like structures evolved early in dinosaur evolution and became more complex over time, potentially appearing in various forms across different dinosaur groups. This has led to heated debates about how widespread feathers were among dinosaurs, with some paleontologists suggesting even early dinosaurs may have had some form of filamentous body covering.

Color and Pattern: The New Frontier

For most of paleontological history, the colors of dinosaurs remained entirely speculative, considered beyond the reach of scientific investigation. This changed dramatically in 2010 when scientists identified melanosomes—cellular structures containing pigment—in fossilized feathers. By comparing these ancient melanosomes with those in modern birds, researchers could determine the original colors of some feathered dinosaurs. Microraptor, for instance, has been shown to have had iridescent black feathers similar to modern crows. Sinosauropteryx featured a reddish-brown and white striped tail, suggesting camouflage patterns. Other studies have revealed countershading in dinosaurs like Psittacosaurus, with lighter undersides and darker upper surfaces—a common camouflage strategy in modern animals. While these techniques only work under exceptional preservation conditions and are limited to certain types of pigments, they have opened an exciting new dimension in dinosaur reconstruction, allowing paleontologists to move beyond grayscale guesswork to evidence-based coloration for some species.

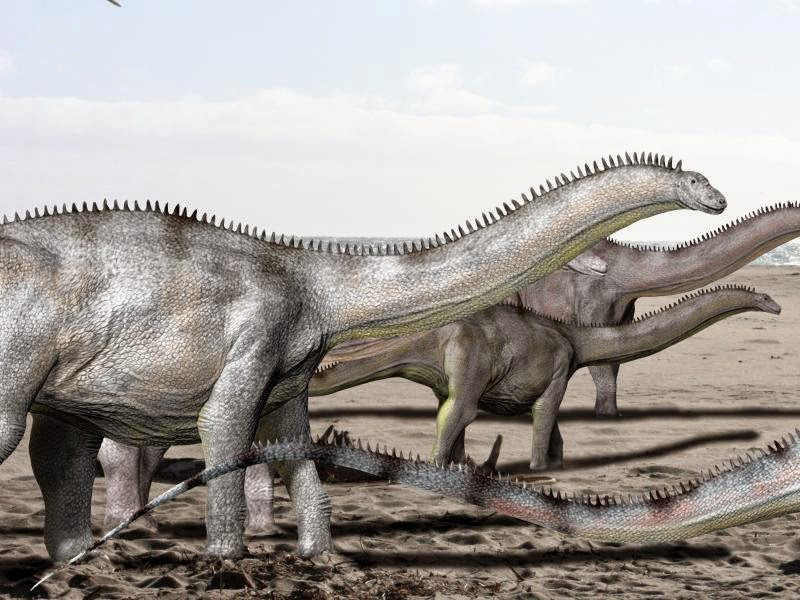

Soft Tissue Reconstruction Challenges

Even with a complete skeleton, determining how a dinosaur’s soft tissues were arranged poses significant challenges. Muscles, fat deposits, cartilage, and other soft structures rarely fossilize, leaving considerable uncertainty about body contours. Paleontologists use various methods to address this gap, including the Extant Phylogenetic Bracket approach, which examines soft tissues in the closest living relatives—birds and crocodilians—to inform reconstructions. Muscle attachment sites on bones provide important clues about muscle placement and size, though the precise shape and bulk remain speculative. Digital modeling has become increasingly important, allowing scientists to test functional hypotheses about soft tissue arrangements. The question of how fat or thin dinosaurs were remains particularly contentious. Early reconstructions often showed dinosaurs as gaunt, with skin tightly wrapped around bone and muscle, while some modern interpretations suggest certain dinosaurs may have carried substantial fat deposits that significantly altered their silhouettes. These uncertainties mean that the same skeleton could produce markedly different-looking reconstructions depending on soft tissue assumptions.

The Science of Comparative Anatomy

When direct evidence is lacking, paleontologists turn to comparative anatomy to fill gaps in dinosaur reconstructions. This approach involves studying anatomical patterns across related living and extinct species to make informed predictions about unknown features. Birds, as living dinosaurs, provide essential insights into theropod dinosaur biology, while crocodilians offer comparative data for more distantly related dinosaur groups. The position and size of eyes, for example, can often be determined from skull openings, while nasal passages and related soft tissues can be inferred from the structure of nasal bones. Comparative studies also help scientists understand how physical features correlate with habitat, diet, and behavior. For instance, eye shape and positioning in modern animals correlate with predatory behavior and activity patterns, allowing reasonable inferences about extinct dinosaurs with similar adaptations. While this approach can’t provide certainty, it grounds reconstructions in biological principles rather than pure speculation, creating plausible visualizations based on evolutionary patterns observed across reptiles and birds.

Digital Reconstruction and Biomechanical Analysis

Advanced technology has revolutionized the way scientists visualize extinct animals, including dinosaurs. Computer modeling allows paleontologists to create detailed three-dimensional reconstructions based on fossil evidence, testing hypotheses about appearance and function. CT scanning of fossils reveals internal structures and features that might be missed in traditional examination, providing data for more accurate models. Biomechanical analysis uses engineering principles to test how dinosaur bodies functioned, including how they moved, their potential speed, and physical capabilities. These analyses often challenge long-held assumptions about dinosaur appearance and behavior. For instance, studies of Tyrannosaurus rex have used biomechanical models to estimate its running capabilities, suggesting it was slower than depicted in films like Jurassic Park. Digital muscle simulations help determine plausible muscle arrangements and body proportions, creating reconstructions that are not only visually compelling but also anatomically and physically viable. This integration of paleontology with engineering and computer science continues to refine our understanding of dinosaur appearance.

Famous Misconceptions in Dinosaur Imagery

Popular culture has perpetuated numerous misconceptions about dinosaur appearance that contradict scientific evidence. Perhaps the most persistent is the depiction of large theropods like Tyrannosaurus with permanently exposed teeth and lips unable to cover them, creating a perpetual snarl. Recent research suggests most dinosaurs likely had lips covering their teeth when the mouth was closed, similar to many modern reptiles. Another common error involves dinosaur posture, particularly the tendency to portray theropods with pronated “bunny hands” facing palms-down—an anatomically impossible position based on their joint structure. Dinosaur tails are frequently depicted dragging on the ground in older media, despite evidence that most were held rigid as counterbalances. The portrayal of dinosaurs with lizard-like or crocodilian skin textures ignores evidence of diverse integumentary structures, including scales, scutes, and feathers. Even Jurassic Park, while revolutionary for its time, featured dinosaurs now known to be inaccurate, such as featherless Velociraptors and Dilophosaurus with fictional neck frills and venom. These misconceptions demonstrate how pop culture imagery can lag behind scientific understanding, sometimes by decades.

The Artistic Interpretation Factor

The gap between scientific evidence and visual reconstruction necessitates artistic interpretation, making dinosaur depictions a unique blend of science and art. Even with the most rigorous scientific approach, artists must make countless decisions about features not preserved in fossils, from precise muscle definition to behavioral poses and environmental context. Color schemes, particularly for dinosaurs without preserved pigmentation evidence, remain largely speculative, guided by ecological principles but ultimately by artistic choices. Different paleoartists may produce noticeably different reconstructions of the same dinosaur while remaining faithful to the fossil evidence. These variations reflect not just artistic style but different interpretations of ambiguous evidence. The collaborative relationship between paleontologists and paleoartists has become increasingly important, with scientists providing anatomical guidance while artists bring technical skill and creative vision. This partnership has elevated paleoart from pure speculation to a discipline that communicates current scientific understanding while acknowledging inherent uncertainties. The best modern paleoart represents a thoughtful balance between scientific accuracy and visual storytelling, recognizing both the constraints of the evidence and the need for engaging, plausible interpretations.

Regional Variations and Species Diversity

Our understanding of dinosaur appearance is further complicated by the likelihood of significant variation within species—a factor often overlooked in reconstructions. Modern animals typically display considerable individual variation, sexual dimorphism, and regional differences within the same species. Dinosaurs likely exhibited similar diversity, with individuals varying in size, proportions, and coloration. Some dinosaur species show evidence of sexual dimorphism, with potential differences between males and females in features like crests, horns, or body size. The duck-billed hadrosaur Parasaurolophus, for instance, may have had differently sized cranial crests between sexes. Geographic isolation likely led to regional variants within widespread dinosaur species, similar to subspecies in modern animals. Seasonal changes might have affected appearance as well, with possibilities including molting patterns, seasonal fat storage, or breeding colors. Most reconstructions present a standardized, generic version of each dinosaur species, but the reality was likely much more varied. This diversity of appearance within species represents another layer of complexity in accurately visualizing dinosaurs, reminding us that even the most scientifically rigorous reconstruction represents just one possible version of an animal that lived millions of years ago.

The Future of Dinosaur Visualization

The science of reconstructing dinosaur appearance continues to advance rapidly, promising even more accurate visualizations in the future. Emerging technologies like synchrotron radiation and advanced microscopy techniques are revealing previously undetectable details in fossils, including soft tissue traces and cellular structures. Chemical analysis of fossil remains increasingly provides data about original biological compounds that can inform reconstructions. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being applied to paleontological problems, helping to identify patterns and relationships that might not be obvious to human researchers. These technologies may eventually allow more automated and objective reconstructions based on comparative data from thousands of species. Virtual and augmented reality technologies are creating new ways to visualize dinosaurs, allowing scientists and the public to experience reconstructions in interactive, three-dimensional environments. As our understanding of evolutionary developmental biology improves, scientists can make more informed predictions about dinosaur features based on genetic and developmental patterns observed in living animals. While uncertainties will always remain, the continuing integration of paleontology with cutting-edge technology promises increasingly sophisticated and evidence-based visualizations of these fascinating prehistoric creatures.

Conclusion: Educated Reconstructions Rather Than Definitive Portraits

Our visualizations of dinosaurs represent the current state of scientific knowledge—constantly evolving hypotheses rather than definitive portraits. Each reconstruction balances direct fossil evidence with comparative anatomy, functional analysis, and necessary artistic interpretation. While we’ve made remarkable progress in understanding dinosaur appearance, significant uncertainties remain and will likely persist due to the inherent limitations of the fossil record. Rather than seeing this as a failure of paleontology, we should recognize it as an honest acknowledgment of the challenges in reconstructing animals that lived millions of years ago. The changing face of dinosaurs in science and popular culture reflects the dynamic nature of scientific inquiry, with each new discovery refining and sometimes revolutionizing our understanding. Future generations will undoubtedly look back on today’s dinosaur reconstructions as we now view Victorian-era depictions—as products of their time that captured the best available knowledge while missing details revealed by subsequent research. This ongoing refinement of dinosaur imagery is not a weakness but a strength of paleontology, demonstrating how science continually tests and improves its understanding of the past.