Dinosaurs have captivated human imagination since their fossils were first scientifically identified in the early 19th century. However, our visual understanding of these prehistoric creatures has evolved dramatically over time. The earliest artistic renditions of dinosaurs were often wildly inaccurate, reflecting the limited scientific knowledge available and the cultural biases of their eras. These fascinating early interpretations—ranging from lumbering lizards to upright dragons—tell us as much about human imagination and the development of paleontology as they do about the actual creatures they attempted to portray. This article explores the remarkable history of early dinosaur art, from Victorian misconceptions to mid-20th-century reimaginings, revealing how our visual understanding of dinosaurs has been shaped by both science and speculation.

The Victorian Dawn of Dinosaur Visualization

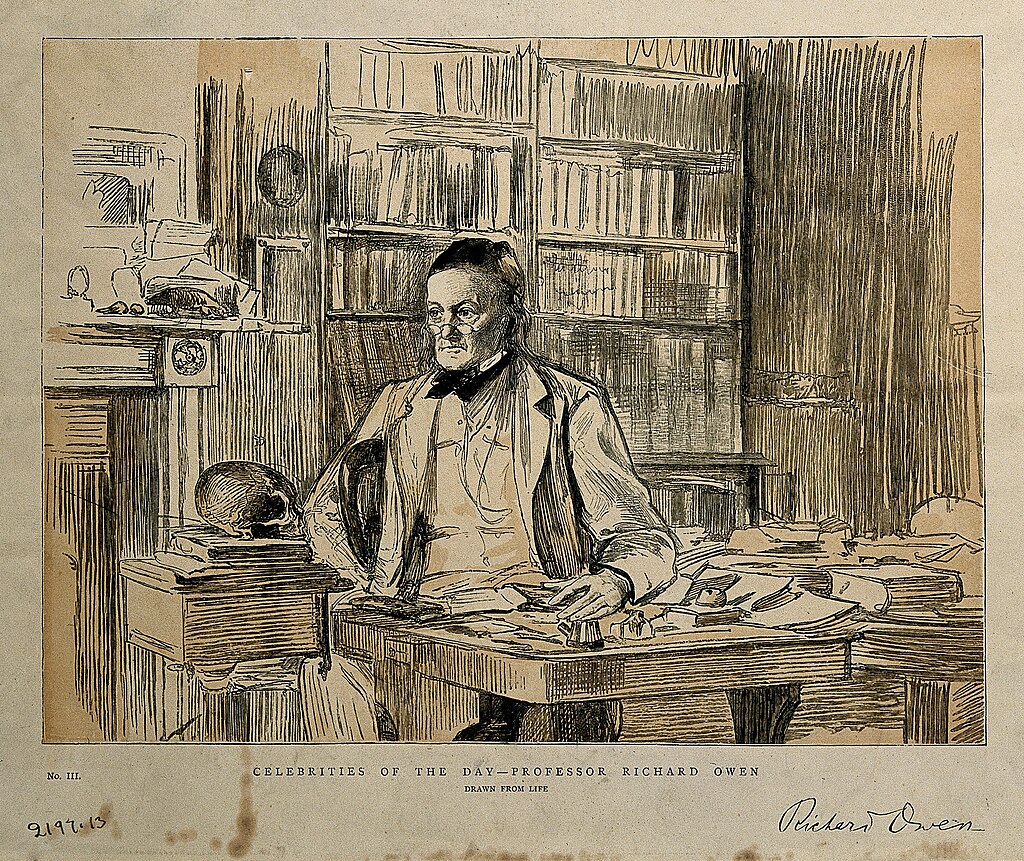

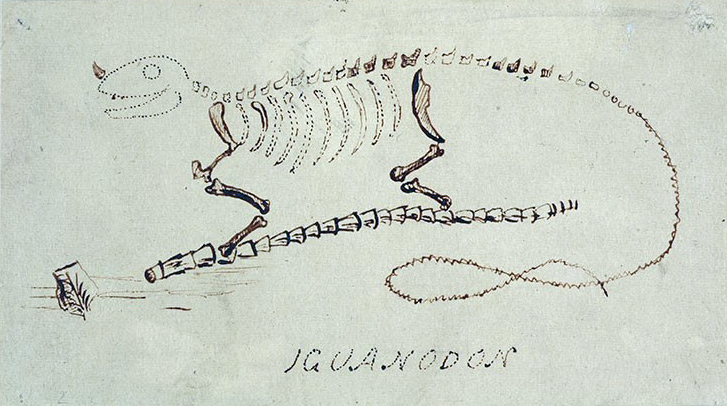

When dinosaurs first entered the scientific and public consciousness in the early 19th century, artists faced the daunting challenge of visualizing creatures known only from fragmentary fossils. The very first influential dinosaur reconstructions emerged in the 1850s, most notably with Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’ sculptures for the Crystal Palace exhibition in London. Working under the guidance of paleontologist Richard Owen, Hawkins created massive concrete sculptures depicting Iguanodon as a hefty, quadrupedal creature resembling a bizarre rhinoceros-lizard hybrid. These sculptures, which still stand today, show Iguanodon with its famous thumb spike erroneously placed on its nose like a horn—a misinterpretation that persisted for decades. The Crystal Palace dinosaurs, despite their inaccuracies, represented the first serious attempt to translate scientific findings into three-dimensional forms that the public could comprehend and appreciate, establishing a visual tradition that would influence dinosaur representation for generations.

Scientific Limitations Behind Early Misconceptions

Early paleontologists worked with severely limited evidence, often having only a handful of bones from which to reconstruct an entire animal. This fragmentary evidence led to fundamental misconceptions about dinosaur posture, movement, and overall appearance. Scientists frequently relied on living reptiles like lizards and crocodiles as anatomical models, assuming dinosaurs shared similar characteristics and limitations. The resulting reconstructions typically featured dinosaurs with sprawling limbs, dragging tails, and generally sluggish dispositions—a far cry from the dynamic, often bird-like creatures we recognize today. The very term “dinosaur,” coined by Richard Owen in 1842, meaning “terrible lizard,” reinforced this reptilian framework that dominated early interpretations. Compounding these challenges, early excavation techniques sometimes damaged fossils or failed to preserve crucial anatomical relationships between bones, further limiting scientists’ ability to accurately understand dinosaur anatomy and leading to representations that seem almost comically inaccurate by modern standards.

Charles R. Knight and the American Revolution

American artist Charles R. Knight revolutionized dinosaur art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, creating what became the definitive dinosaur imagery for generations. Knight worked closely with paleontologists at the American Museum of Natural History, including Henry Fairfield Osborn, to create meticulously researched (for their time) murals and paintings of prehistoric life. His famous 1897 painting of a duel between Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops remains one of the most iconic dinosaur images ever created, establishing the popular conception of T. rex as the ultimate prehistoric predator. Unlike earlier artists, Knight imbued his dinosaurs with a sense of life and vigor, depicting them as active, muscular animals rather than sluggish reptiles. Though many of Knight’s reconstructions now appear outdated—with dinosaurs typically portrayed as tail-dragging, cold-blooded reptiles—his artistic approach set new standards for paleontological illustration by combining scientific rigor with dramatic composition and a naturalist’s eye for animal behavior and anatomy. Knight’s influence was so profound that his visions of dinosaurs dominated books, museums, and popular culture for nearly half a century.

The Upright Tail-Draggers Era

From the 1900s through the 1960s, dinosaur art settled into a fairly consistent pattern that paleontologist Robert Bakker would later derisively term “the upright tail-draggers.” During this period, dinosaurs were almost universally depicted with vertical limbs beneath their bodies—an improvement over the earlier sprawling models—but still dragging their tails along the ground like enormous lizards. This visual paradigm dominated museum displays, children’s books, and films for decades. Perhaps the most influential artistic proponent of this style was Rudolph Zallinger, whose massive 1947 mural “The Age of Reptiles” at Yale’s Peabody Museum became a defining image of dinosaurs for the mid-20th century. The mural portrayed dinosaurs as ponderous, slow-moving creatures in muted colors, reinforcing the then-prevailing scientific view of dinosaurs as evolutionary failures destined for extinction. This artistic convention became so entrenched that even as evidence mounted against it in the 1960s, most artists and museums were slow to adopt more accurate representations, demonstrating how powerful established visual traditions can be in shaping public understanding of prehistoric life.

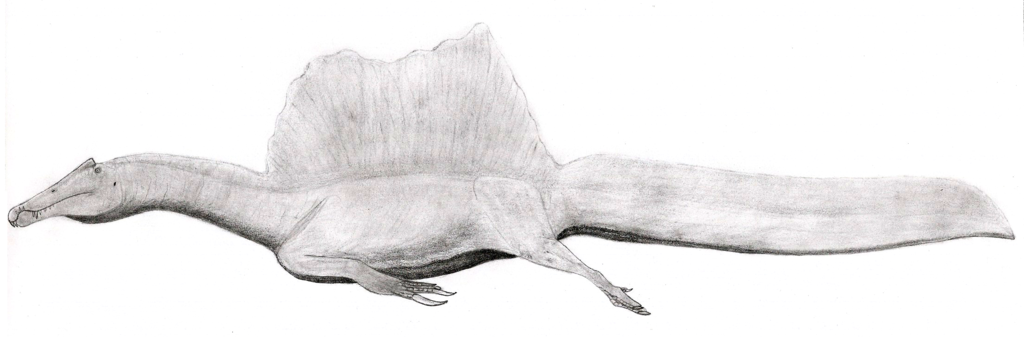

Bizarre Anatomical Errors in Early Reconstructions

Early dinosaur reconstructions contained anatomical errors that seem astonishing from our modern perspective. Perhaps the most famous example is the case of Iguanodon’s thumb spike, which was initially placed on the animal’s nose like a rhinoceros horn until more complete specimens clarified its true position. Similarly, early reconstructions of Diplodocus and other sauropods often showed them with nostrils positioned at the top of their heads like modern whales, based on the mistaken interpretation of skull openings. Stegosaurus was frequently depicted with a second brain in its hip region to control its rear quarters—a misconception arising from the enlarged neural canal in the sacral region that actually housed a glycogen body, similar to those found in modern birds. Even more fundamentally, many early dinosaur skeletons were assembled incorrectly, with the wrong number of vertebrae, misaligned limbs, or completely invented elements filling in gaps in the fossil record. These errors weren’t simply artistic liberties but represented the genuine scientific understanding of their time, highlighting how paleontological interpretation progresses through correction and refinement as more evidence becomes available.

The Cultural Context of Victorian Dinosaur Art

Victorian-era dinosaur art was profoundly shaped by the cultural and philosophical environment of the 19th century. This was a period when European imperial powers were expanding their colonial reach, and narratives of progress and hierarchy dominated Western thinking. These cultural contexts influenced how dinosaurs were visualized and understood. Early reconstructions often portrayed dinosaurs as failures of evolution—sluggish, dim-witted creatures destined for extinction—reinforcing a progressive view of life that placed humans at the pinnacle of evolutionary development. Artistic depictions frequently emphasized characteristics that made dinosaurs seem alien and inferior to mammals, aligning with the period’s hierarchical worldview. The Victorian fascination with monsters and the exotic also influenced these early visualizations, with dinosaurs often portrayed with exaggerated features that emphasized their strangeness and ferocity. This was particularly evident in popular illustrations for magazines and books, which frequently depicted dinosaurs as dragon-like monsters engaged in constant, violent combat—a vision that said more about Victorian sensibilities and anxieties than about prehistoric reality.

Dinosaurs in Early Popular Culture

Early artistic reconstructions of dinosaurs quickly transcended scientific publications to become fixtures in popular culture, shaping public imagination about prehistoric life. Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel “The Lost World” featured dinosaurs based on contemporary scientific reconstructions, popularized through striking illustrations by Czech artist Zdeněk Burian that showed dramatic scenes of humans encountering living dinosaurs. The 1925 film adaptation of “The Lost World” featured groundbreaking stop-motion animation by Willis O’Brien, bringing these early visions of dinosaurs to life on the screen for the first time. Comic strips like “Alley Oop,” which debuted in 1932, featured a caveman protagonist riding a dinosaur, further cementing the inaccurate but popular notion that humans and dinosaurs coexisted. Children’s books from this era typically presented dinosaurs as fearsome monsters or gentle giants based on museum displays and scientific illustrations of the time, complete with all their anatomical inaccuracies. These popular depictions created a feedback loop, where artistic visions initially derived from science became so culturally entrenched that they influenced future scientific and artistic interpretations, sometimes making it harder for more accurate reconstructions to gain acceptance.

The Burian-Augusta Partnership

The collaboration between Czech artist Zdeněk Burian and paleontologist Josef Augusta in the mid-20th century created some of the most influential dinosaur art of its era, reaching a global audience through widely translated and distributed books. Burian’s paintings, created between the 1930s and 1970s, struck a remarkable balance between scientific accuracy (for their time) and artistic dynamism, showing dinosaurs in atmospheric, naturalistic settings with a painter’s attention to light and composition. Unlike many contemporaries, Burian frequently depicted dinosaurs in active postures—hunting, fighting, or caring for young—suggesting a more complex understanding of their biology than the sluggish reptiles of earlier eras. While still showing tail-dragging postures and lacking feathers on theropods, Burian’s work was progressive in many ways, particularly in his attention to musculature and environmental context. His paintings of Brachiosaurus standing in deep water to support its weight reflected the then-current hypothesis about sauropod lifestyles, while his depictions of theropods showed them as alert, intelligent predators rather than mindless monsters. Though largely superseded by more accurate reconstructions, Burian’s artwork remains significant for its artistic quality and its role in elevating dinosaur art to a more sophisticated level.

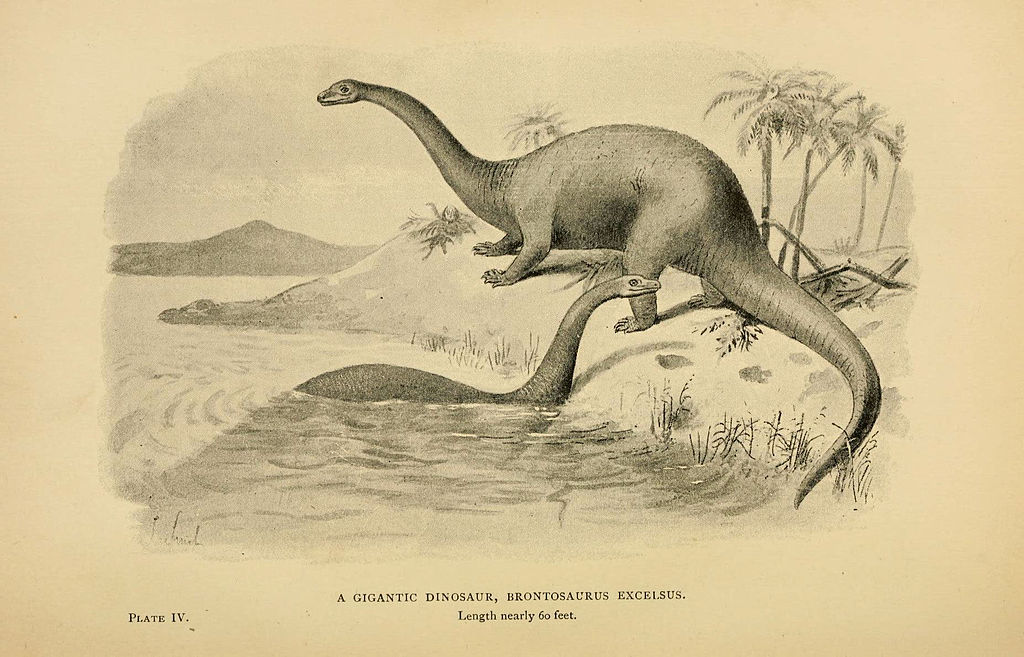

The Persistent Power of “Brontosaurus”

Few prehistoric creatures better illustrate the gap between scientific understanding and public imagination than “Brontosaurus.” Despite the scientific community recognizing as early as 1903 that Brontosaurus was actually a misidentified Apatosaurus, the name and distinctive image persisted in popular culture throughout most of the 20th century. Sinclair Oil’s adoption of a Brontosaurus-like sauropod as its corporate mascot in the 1930s cemented this dinosaur in American consciousness, appearing on everything from gas station signs to the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair. The iconic dinosaur hall at the American Museum of Natural History displayed a “Brontosaurus” skeleton for decades, influencing countless artistic depictions in books, magazines, and films. These representations typically showed Brontosaurus partially submerged in swamps to support its supposedly cumbersome weight—a misconception that persisted in artwork long after scientists had recognized sauropods as fully terrestrial animals. The public attachment to Brontosaurus was so strong that when paleontologists in the 2010s suggested that Brontosaurus might actually be a valid genus distinct from Apatosaurus after all, the news was met with widespread public celebration, demonstrating how deeply early artistic visions of dinosaurs can embed themselves in cultural memory, sometimes outlasting the scientific understanding that initially inspired them.

The Shifting Colors of Prehistoric Life

The coloration of dinosaurs in early artistic reconstructions reveals much about the changing relationship between science, art, and speculation. Early Victorian artists like Waterhouse Hawkins typically depicted dinosaurs in dull greys and greens, reflecting both their supposed reptilian nature and the conservative aesthetic of scientific illustration of the period. By the early 20th century, artists began introducing more varied coloration, though still largely constrained to reptilian patterns and earthy tones. Charles R. Knight broke new ground by occasionally giving his dinosaurs more vivid coloration and patterning based on his extensive knowledge of modern animal camouflage and display. Mid-century artists like Burian and Zallinger generally returned to more subdued color palettes, perhaps influenced by the scientific sobriety of their era or the limitations of printing technology. Throughout this period, the colors chosen for dinosaur art were entirely speculative, based on loose analogies with modern reptiles rather than fossil evidence. This situation created a circular problem where artistic depictions influenced public and even scientific expectations of what dinosaurs “should” look like, despite having no empirical basis. Only in recent decades have scientists developed techniques to identify actual color patterns in some fossils, revealing that at least some dinosaurs had complex patterns and bright colors closer to modern birds than reptiles—a discovery that vindicated some of the more colorful artistic speculations of earlier eras.

When Dinosaurs Swam in the Deep

Among the most persistent misconceptions in early dinosaur art was the portrayal of sauropods as primarily aquatic animals that used water to buoy their massive bodies. This hypothesis, championed by paleontologist Frederic Augustus Lucas in the early 20th century, led to decades of artwork showing Diplodocus, “Brontosaurus,” and other long-necked dinosaurs submerged in swamps with only their heads protruding above the surface. Rudolph Zallinger’s influential mural “The Age of Reptiles” reinforced this image, as did countless illustrations in books and magazines throughout the mid-20th century. The aquatic sauropod theory extended beyond mere artistic convention—museums around the world mounted sauropod skeletons in poses suggesting they could not support their weight on land, further cementing this interpretation in public consciousness. This view persisted despite mounting evidence to the contrary, including fossilized trackways showing sauropods walking on solid ground and anatomical studies revealing adaptations for terrestrial locomotion. The aquatic sauropod represents a fascinating case where artistic depictions both reflected and reinforced scientific misconceptions, creating a visual tradition so powerful that it continued to appear in popular books and films long after scientists had abandoned the theory. When paleontologists in the 1970s conclusively demonstrated that sauropods were fully terrestrial animals with anatomical adaptations for supporting their weight on land, artists had to fundamentally reimagine these iconic dinosaurs.

The Dinosaur Renaissance and Artistic Revolution

The Dinosaur Renaissance of the late 1960s and 1970s marked a fundamental turning point in dinosaur art, as revolutionary scientific ideas demanded equally revolutionary artistic visions. Led by paleontologists like John Ostrom and Robert Bakker, this intellectual movement reinterpreted dinosaurs as active, warm-blooded animals more closely related to birds than to modern reptiles. Bakker’s own distinctive pen-and-ink illustrations—showing dynamic, muscular dinosaurs in alert, energetic poses—helped popularize this new vision, appearing in scientific papers and popular articles. Artist Sarah Landry’s illustrations for Bakker’s 1975 article “The Dinosaur Renaissance” in Scientific American presented readers with startlingly new images of dinosaurs as agile, intelligent creatures with upright postures and raised tails. Following this shift, a new generation of paleoartists emerged, including Gregory S. Paul, whose technically precise skeletal reconstructions and life restorations established new standards for anatomical accuracy in dinosaur art. By the 1980s, the visual transformation was dramatic—dinosaurs in books, museums, and films increasingly appeared as active, bird-like creatures rather than the lumbering reptiles of earlier decades. This artistic revolution wasn’t merely cosmetic but reflected fundamental changes in scientific understanding, demonstrating how artistic representation and scientific knowledge evolve together, each influencing the other in an ongoing dialogue about how we visualize the prehistoric past.

Legacy and Lessons of Early Dinosaur Art

The wild guesses and bizarre designs of early dinosaur art serve as powerful reminders of the provisional nature of scientific knowledge and the challenges of visualizing the distant past. These historical reconstructions, despite their inaccuracies, played a crucial role in making paleontology accessible to the public and inspiring generations of future scientists. Many leading paleontologists cite childhood encounters with Knight’s paintings or Burian’s illustrations as formative experiences that sparked their scientific careers. Early dinosaur art also provides valuable insights into the cultural contexts that shape scientific interpretation—revealing how Victorian ideas about progress influenced dinosaur reconstructions or how Cold War-era attitudes toward nature affected mid-century paleoart. Perhaps most importantly, the evolution of dinosaur art demonstrates the vital interplay between scientific evidence and creative imagination in our attempts to understand extinct life forms. Even today’s most scientifically rigorous dinosaur reconstructions involve elements of artistic interpretation and educated guesswork, particularly regarding soft tissues, behaviors, and coloration. The history of dinosaur art teaches us to hold our visual reconstructions of the past with a certain humility, recognizing them as our best current understanding rather than definitive portraits—representations that will continue to evolve as