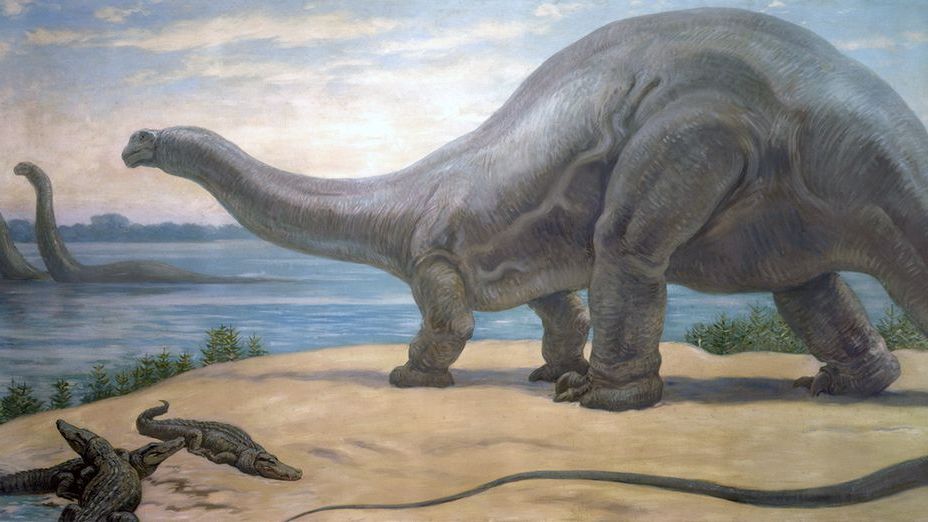

When you picture dinosaurs, what comes to mind? Ferocious predators with razor-sharp teeth? Thunderous roars echoing through prehistoric landscapes? Maybe creatures locked in deadly combat? It’s easy to fall into that mental trap.

Hollywood has done an exceptional job convincing us that dinosaurs were basically oversized monsters. Here’s the thing though – the largest creatures ever to walk the Earth weren’t the terrifying carnivores we’ve been trained to fear. They were something completely different. The true titans of the dinosaur world were plant-eaters, and despite their mind-boggling size, they lived surprisingly peaceful lives. Think about that for a second: an animal weighing as much as ten elephants that just wanted to munch on leaves all day.

These reptiles were the largest of all dinosaurs and the largest land animals that ever lived. Yet they weren’t out hunting prey or terrorizing smaller creatures. So let’s dive in and discover why being absolutely enormous didn’t mean being dangerous at all.

The Colossal Anatomy of Peaceful Giants

Sauropods were marked by large size, a long neck and tail, a four-legged stance, and a herbivorous diet. Imagine standing next to one of these creatures and looking up. Your neck would hurt just trying to see the top.

Their bodies were evolutionary masterpieces designed not for destruction but for reaching vegetation. They had very long necks, long tails, small heads relative to the rest of their body, and four thick, pillar-like legs. Those pillar-like legs weren’t built for speed or agility – they were support columns for carrying unimaginable weight across ancient landscapes. The long neck served as a biological crane, allowing them to access food sources other dinosaurs couldn’t dream of reaching. Their tails? Likely used for balance and possibly as a defensive whip if absolutely necessary, though evidence suggests they preferred flight over fight.

Record-Breaking Sizes That Defy Imagination

Let’s talk numbers, because honestly, they’re almost impossible to wrap your head around. Argentinosaurus huinculensis is the largest dinosaur known from uncontroversial and relatively substantial evidence, estimated to have been 70–80 t and 36 m long.

That’s roughly the length of three school buses parked end to end. The titanosaur, named Patagotitan mayorum, was estimated to have been around 40 m long weighing around 77 t, larger than any other previously found sauropod. We’re talking about animals that could peek into fourth-story windows if buildings existed back then. Even the smaller sauropods were giants by any reasonable standard. Brachiosaurus was one of the largest and most massive of all known dinosaurs, reaching a length of 30 metres and a weight of 80 metric tons. Yet all this bulk was devoted to one simple purpose: eating plants.

Gentle Feeding Habits of Nature’s Lawnmowers

Despite weighing more than a dozen elephants, these giants survived on salad bars. Argentinosaurus relied on a diet of plants, including ferns, cycads and conifer trees, and its long neck allowed it to graze on vegetation at various heights.

Picture it: a creature that could crush you accidentally just by shifting its weight, delicately stripping leaves from branches. Patagotitan didn’t chew its food – it swallowed vegetation whole, relying on a complex digestive system to break down the tough plant material. That’s right, they didn’t even bother chewing. Diplodocus and other sauropods were not capable of chewing. They simply plucked, swallowed, and let their massive digestive systems handle the rest. It’s hard to say for sure, but some scientists estimate they consumed hundreds of kilograms of plant matter daily just to maintain their colossal frames. Honestly, that sounds exhausting.

Social Creatures Living in Protective Herds

You might assume animals this large would be solitary giants wandering alone. Wrong. Argentinosaurus is thought to have been a social animal, living in herds to provide protection from predators.

Evidence from trackways and nesting sites reveals something surprising about these peaceful behemoths. Numerous sauropod footsteps preserved in limestone showed tracks that are nearly parallel and all progress in the same direction, suggesting the sauropod trackmakers passed in a single herd. Imagine the ground-shaking spectacle of dozens of these giants moving together across floodplains. The multiple Mussaurus aggregations in the Early Jurassic breeding ground are interpreted as the oldest skeletal evidence of structured age-segregated gregariousness amongst dinosaurs. They organized themselves, separated by age groups, and traveled together for safety and social bonding. That’s not monster behavior – that’s sophisticated social organization.

Evolutionary Advantages of Enormous Size

Here’s where things get interesting from a survival perspective. There are several proposed advantages for the large size of sauropods, including protection from predation, reduction of energy use, and longevity.

Being absolutely massive meant very few predators could realistically threaten an adult. As an adult, its sheer size would have made it almost invincible and a real danger to any predator that may have been stupid enough to attack it. Sure, carnivores might pick off juveniles or sick individuals, but a healthy adult sauropod? Virtually untouchable. Large animals are more efficient at digestion than small animals, because food spends more time in their digestive systems, permitting them to subsist on food with lower nutritive value. So getting big wasn’t just about defense – it was an entire lifestyle adaptation that made survival easier, not harder.

Resource Partitioning Among Gentle Neighbors

Multiple massive herbivores coexisting in the same environment sounds like a recipe for competition, right? Nature found a clever workaround. Diplodocus ate plants low to the ground and Camarasaurus browsed leaves from top and middle branches – the specializing of their diets helped the different herbivorous dinosaurs to coexist.

Each species carved out its own ecological niche. While Brachiosaurus ate leaves from the top of trees, the Diplodocus dinosaur ate plants that grew nearer to the ground and in the middle areas. Brilliant, really. By feeding at different heights and targeting different plant types, these gentle giants avoided direct competition. Brachiosaurus has a mild temperament and likes to live in groups – in order to satisfy their big appetite, they often migrate in groups. They moved together peacefully, each taking what they needed without conflict. It’s almost poetic how these enormous creatures managed to share resources harmoniously.

Defensive Strategies Without Aggression

So how did creatures built for peace survive in a world with massive predators? Size was the first line of defense, obviously. Argentinosaurus likely relied on their sheer size as a defense mechanism – their massive bodies would have made them formidable opponents for most predators, and their herding behavior may have provided additional protection by strength in numbers.

Think about it from a predator’s perspective. Giganotosaurus preyed on some of the largest herbivores of its time, including massive sauropods, such as Argentinosaurus. Even the most fearsome carnivores had to think twice before attacking. Group living amplified this advantage. A herd of sauropods moving together created a wall of flesh and bone that few predators would dare approach. Diplodocids possessed tremendously long tails, which they may have been able to crack like a whip as a signal or to deter or injure predators. When pushed, they had options – but aggression was clearly Plan B, not their go-to strategy.

Nesting Behavior and Parental Care

These gentle giants showed remarkably sophisticated reproductive behavior. Similar nests and eggs lying one on top of the other indicate that particular species returned to the same site year after year to lay their clutches – site fidelity was an instinctive part of dinosaurian reproductive strategy.

They weren’t just dropping eggs randomly and walking away. Fossilized nests found in Argentina revealed large clusters of eggs buried in the ground under layers of soil. That’s intentional nest construction and site selection. Evidence shows separation in the deposition of different age groups of dinosaurs – the embryotic eggs were separate from the juveniles, and the juveniles were separated from older individuals – this physical evidence points to a stratified group or herd of dinosaurs, like a troop of elephants today. The comparison to modern elephants is spot-on. These weren’t mindless beasts – they were organized, caring communities raising the next generation together.

The True Temperament Behind the Size

Let’s be real here: everything about sauropod biology points toward gentleness, not ferocity. Herbivore dinosaurs, the gentle giants of the prehistoric world, offer a fascinating glimpse into the diverse and peaceful side of Mesozoic life – these plant-eating dinosaurs played a crucial role in shaping the ecosystems of their time.

Their small heads housed relatively small brains designed for processing plant material, not hunting strategies. Like other sauropods, Apatosaurus had quite a small head and small brain – as a rule, relative brain size is related to diet, and plant eaters get by with smaller brains than meat-eaters, after all, their food doesn’t try to escape. That last bit is particularly telling. They didn’t need cunning or aggression because vegetation doesn’t run away. Despite their massive size and strength, Patagotitan was a gentle giant, feeding on plants and vegetation rather than other animals. Size and gentleness weren’t contradictory – they went hand in hand for these remarkable creatures.

A Legacy of Peaceful Coexistence

The story of the sauropods challenges everything we thought we knew about size and dominance. These gentle giants roamed the planet during the Mesozoic Era, thriving in various environments – their unique features, such as column-like legs and long tails, helped them survive and adapt to their surroundings. For roughly 140 million years, these peaceful giants dominated terrestrial ecosystems not through violence but through adaptation and social cooperation.

These findings provide the earliest evidence of complex social behaviour in Dinosauria – the presence of sociality in different sauropodomorph lineages suggests a possible Triassic origin of this behaviour, which may have influenced their early success as large terrestrial herbivores. Their success story wasn’t written in blood and conquest. It was written in peaceful coexistence, efficient resource utilization, and sophisticated social structures. These animals proved that being the biggest didn’t require being the baddest. They were gentle giants in the truest sense, and honestly, that makes them even more impressive than any Hollywood monster could ever be.

The next time someone mentions dinosaurs being terrifying, maybe remind them of this: the most massive creatures to ever walk on land spent their days peacefully munching leaves in family groups. Size isn’t everything, and sometimes the gentlest souls come in the most enormous packages. What do you think about these peaceful giants? Did you expect that the biggest were also the gentlest?