Among the diverse array of dinosaurs that once roamed North America during the Late Cretaceous period, Gryposaurus stands as one of the most distinctive hadrosaurids ever discovered. Known for its remarkable arched nasal bone that earned it the nickname “hook-nosed lizard,” this duck-billed dinosaur has fascinated paleontologists since its first discovery in the early 20th century. Gryposaurus fossils have been primarily unearthed across the American Southwest, offering valuable insights into the ecosystem of this region approximately 80 million years ago. As we explore this fascinating herbivore, we’ll uncover its unique physical traits, behavioral patterns, evolutionary significance, and the continuing research that helps illuminate its place in prehistoric North America.

The Discovery and Naming of Gryposaurus

The history of Gryposaurus begins in 1913 when paleontologist Barnum Brown discovered the first specimens in what is now Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, Canada. The genus name “Gryposaurus” derives from the Greek words “grypos,” meaning “hook-nose,” and “saur, os,” meaning “lizard,” directly referencing its most distinctive physical feature. Lawrence Lambe formally described the type species, Gryposaurus notabilis, in 1914, establishing it as a new genus of hadrosaur. Subsequent discoveries throughout the 20th and 21st centuries expanded our understanding of this dinosaur, with additional species being identified in Utah and Montana. These discoveries have painted a clearer picture of Gryposaurus’s range across western North America, revealing its prominence in the dinosaur communities of the Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 83 to 75 million years ago.

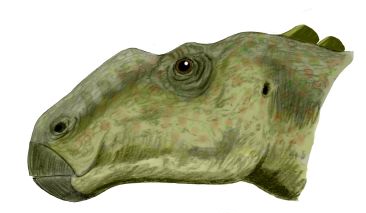

Distinctive Nasal Arch: Gryposaurus’s Defining Feature

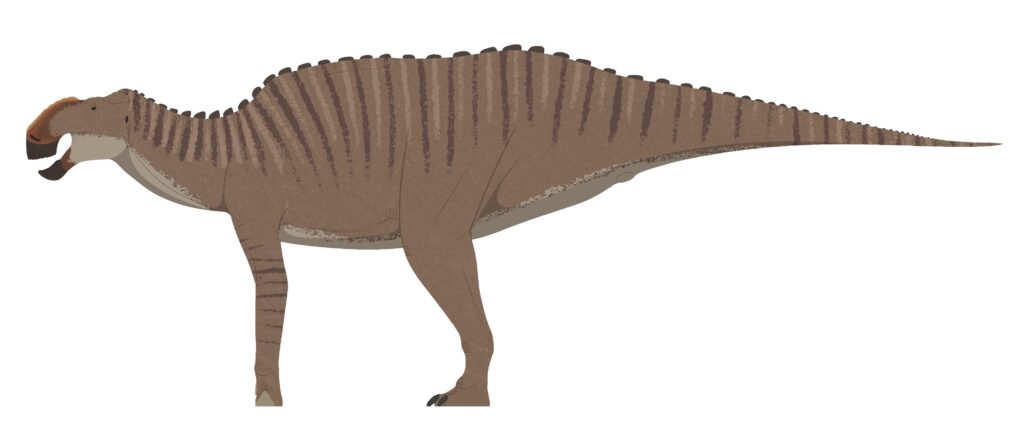

The most striking characteristic of Gryposaurus is undoubtedly its prominent nasal arch, which gives this dinosaur its common name “hook-nosed lizard.” Unlike other hadrosaurs that sported hollow crests or tube-like structures, Gryposaurus possessed a solid, arched nasal bone that curved dramatically upward and backward from the snout. This feature was particularly pronounced in mature individuals, suggesting it may have developed more fully with age. The arch varied somewhat between species, with Gryposaurus monumentensis displaying a particularly robust version. Paleontologists have debated the function of this distinctive feature for decades, with theories ranging from species recognition to serving as an attachment point for powerful muscles that supported its large head. The nasal arch may have also played a role in thermoregulation or possibly functioned as a resonating chamber for communication, though these theories remain speculative without soft tissue preservation.

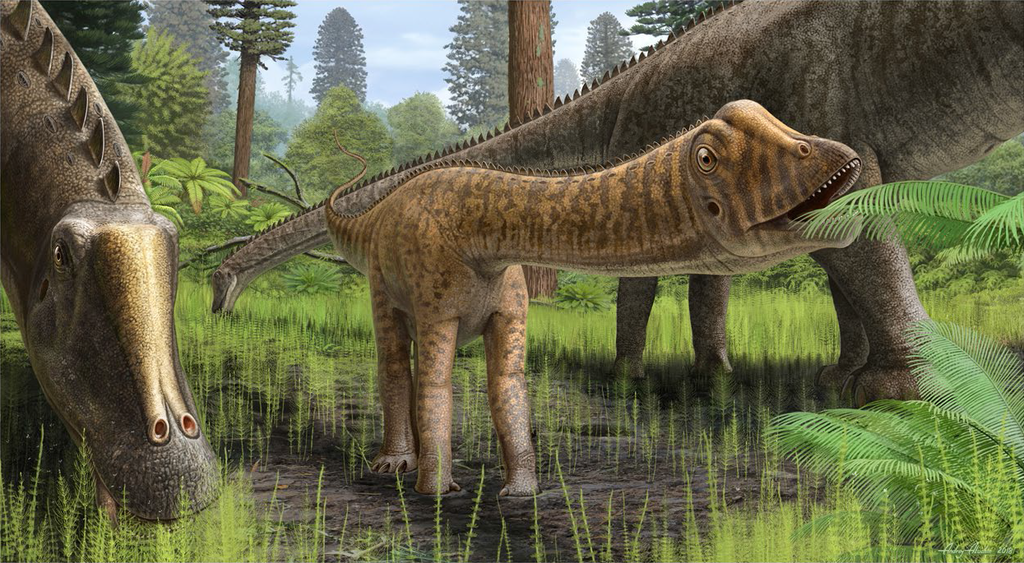

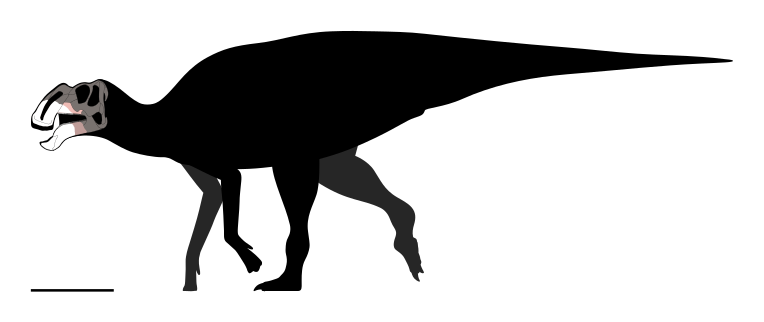

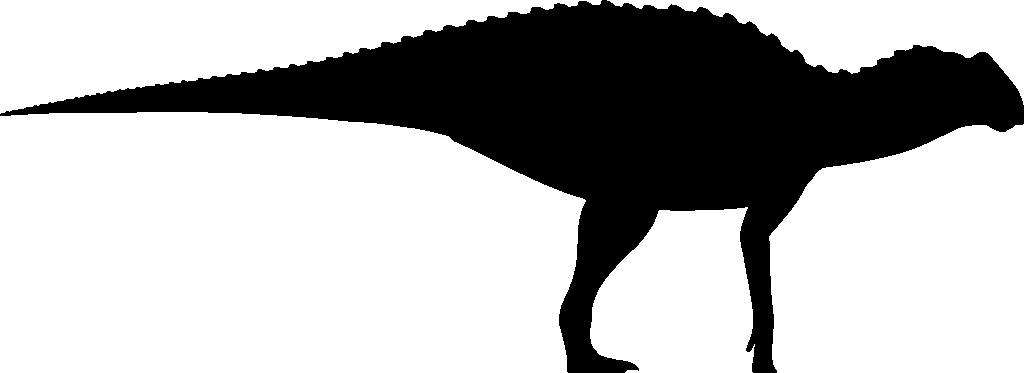

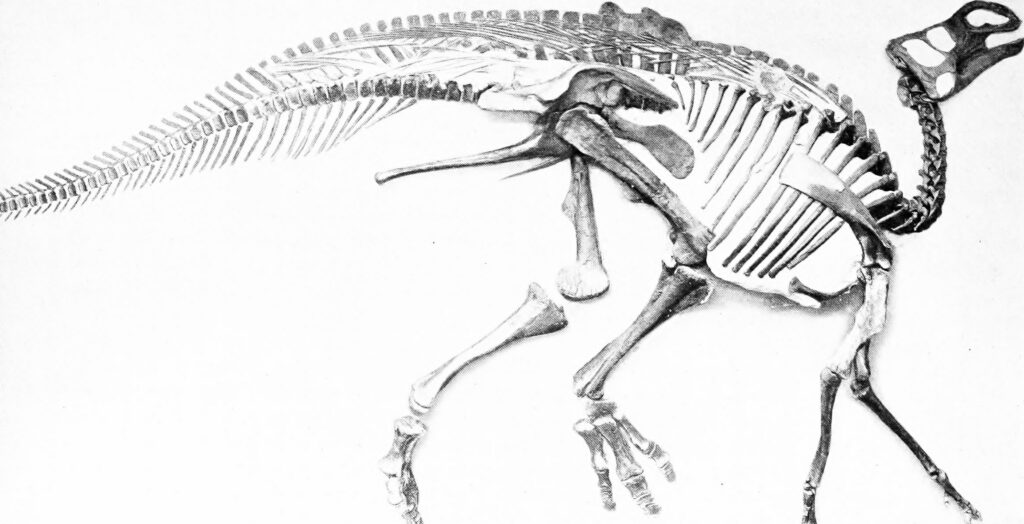

Physical Dimensions and Appearance

Gryposaurus was a substantial dinosaur, reaching lengths of approximately 8 to 10 meters (26 to 33 feet) and weighing between 2 to 3.5 tons when fully grown. Like other hadrosaurs, it possessed a duck-bill-shaped mouth perfectly adapted for its herbivorous diet. The dinosaur walked on all fours most of the time but could likely rise on its powerful hind legs when necessary for feeding or vigilance. Its forelimbs were shorter than its hindlimbs, with five-fingered hands that could grasp vegetation. The powerful tail of Gryposaurus would have provided balance when moving on two legs and might have served as a defensive weapon against predators. Skin impressions discovered with some specimens reveal that Gryposaurus had pebbly, scaled skin rather than feathers, with variations in scale patterns across different parts of its body. The overall coloration remains unknown, though many paleontologists speculate it may have had earthy tones that provided camouflage in its forested habitat.

The Species Diversity of Gryposaurus

The genus Gryposaurus currently includes several recognized species, each with slight variations in anatomy and geographical distribution. Gryposaurus notabilis, the type species, is known primarily from specimens found in Alberta, Canada. Gryposaurus latidens, discovered in Montana’s Two Medicine Formation, features distinct, wide teeth that suggest potential dietary specialization. The youngest known species, Gryposaurus monumentensis, hails from the Kaiparowits Formation in southern Utah and represents one of the largest members of the genus. Some paleontologists have also proposed additional species, including Gryposaurus incurvimanus and Gryposaurus alsatei, though these remain under scientific scrutiny. Each species shows subtle variations in the shape of the nasal arch, tooth structure, and overall size, potentially reflecting adaptations to slightly different ecological niches or evolutionary changes over time. This diversity within the genus provides valuable insights into how these dinosaurs may have specialized and adapted to different environments across their range.

Habitat and Geographic Range

Gryposaurus inhabited what is now the western portion of North America during the Late Cretaceous period, with fossils primarily discovered in the American Southwest and southern Canada. During this time, much of central North America was covered by the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow sea that divided the continent. Gryposaurus lived along the western coastal plains of this seaway, in environments that were considerably warmer and more humid than the modern Southwest. Fossil evidence suggests these dinosaurs thrived in lush, subtropical habitats with abundant vegetation, rivers, and floodplains. The Kaiparowits Formation in Utah, where Gryposaurus monumentensis has been found, preserves evidence of a particularly rich ecosystem with diverse plant life, including conifers, ferns, cycads, and flowering plants. The wide distribution of Gryposaurus species across different formations indicates these dinosaurs were highly successful and adaptable, capable of thriving in slightly different environmental conditions throughout their range.

Feeding Habits and Dietary Adaptations

As a member of the hadrosaur family, Gryposaurus was a highly specialized herbivore with remarkable adaptations for processing plant material. Its duck-bill-shaped mouth contained hundreds of teeth arranged in dental batteries – complex structures where multiple teeth were stacked in columns, with new teeth continuously growing to replace those worn down by use. This evolutionary innovation allowed Gryposaurus to efficiently process tough plant materials through a grinding motion, much like modern ungulates. Analysis of tooth wear patterns suggests these dinosaurs primarily fed on low-growing vegetation, possibly including ferns, cycads, and early flowering plants. The structure of Gryposaurus’s jaw and the mechanics of its skull indicate it had powerful bite forces capable of processing fibrous plant materials that might have been inaccessible to other herbivores. Some paleontologists have proposed that the varying tooth morphology between Gryposaurus species might reflect specialization for different plant resources, allowing multiple species to coexist by reducing direct competition for food.

Social Behavior and Herd Dynamics

While direct evidence of Gryposaurus’s social behavior remains limited, paleontologists have made inferences based on fossil discoveries and comparisons with other hadrosaurs. Multiple individuals found in bone beds suggest these dinosaurs likely lived in herds, a behavior that would have protected them against the large tyrannosaurid predators of their time. Age diversity within these fossil assemblages indicates that herds may have included individuals of various growth stages, from juveniles to fully mature adults. The distinctive nasal arch of Gryposaurus could have played a role in visual recognition among herd members, potentially helping to maintain social cohesion. Some scientists have suggested that, like other hadrosaurs, Gryposaurus may have used vocalizations produced through resonant chambers in their skulls to communicate within herds, though this remains speculative. Trackway evidence from other hadrosaur species supports the theory that these dinosaurs traveled together in groups, a behavior pattern that Gryposaurus likely shared.

Growth and Development

Studies of Gryposaurus fossils representing different growth stages have provided valuable insights into how these dinosaurs developed from hatchlings to adults. Like many dinosaurs, Gryposaurus appears to have grown rapidly during its early years, possibly reaching sexual maturity before attaining full adult size. Histological analysis of bone samples reveals growth rings similar to those in trees, indicating periods of faster and slower growth likely corresponding to seasonal changes in resource availability. The characteristic nasal arch developed progressively throughout the dinosaur’s life, becoming more pronounced in fully mature individuals. This ontogenetic change suggests the arch may have played a role in sexual display or species recognition among adults. Juvenile specimens show proportionally larger eyes and shorter snouts compared to adults, reflecting the allometric growth patterns common in many vertebrates. The estimated lifespan of Gryposaurus remains uncertain, though comparisons with other large herbivorous dinosaurs suggest these animals might have lived for several decades under favorable conditions.

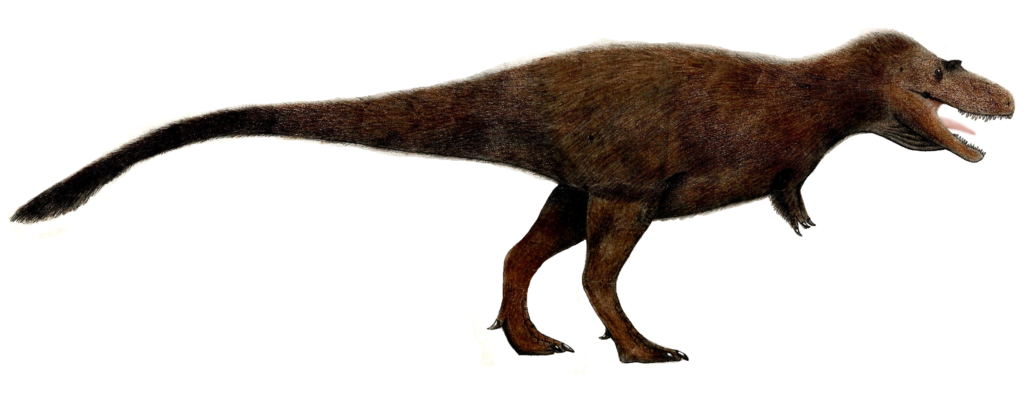

Predators and Defensive Strategies

Living in the predator-rich environments of Late Cretaceous North America, Gryposaurus faced significant threats from contemporary carnivorous dinosaurs. Chief among these predators were tyrannosaurids like Teratophoneus and Gorgosaurus, large theropods capable of bringing down even adult hadrosaurs. Fossil evidence occasionally reveals tooth marks on Gryposaurus bones, providing direct evidence of predation or scavenging. To counter these threats, Gryposaurus likely relied on several defensive strategies. Its impressive size alone would have deterred smaller predators, while its powerful tail could deliver forceful blows when necessary. The herd behavior inferred from fossil assemblages would have provided safety in numbers, with multiple pairs of eyes watching for danger, and the confusion effect making it difficult for predators to target individuals. Some paleontologists speculate that Gryposaurus may have been capable of rapid acceleration, at least for short distances, allowing it to flee from threats when detected early. Additionally, the keen senses suggested by its large eye sockets would have helped it spot approaching predators, giving the herd time to react appropriately.

Paleoenvironmental Context

The ecosystems inhabited by Gryposaurus were remarkably different from the arid landscapes of the modern American Southwest. During the Late Cretaceous, this region experienced a much warmer, more humid climate with abundant rainfall supporting lush vegetation. Gryposaurus shared its habitat with a diverse assemblage of other dinosaurs, including fellow hadrosaurs, ceratopsians like Utahceratops, armored ankylosaurs, and various theropod predators. The waterways and wetlands of these environments supported turtles, crocodilians, fish, and amphibians, while the skies held pterosaurs and early birds. Plant life was dominated by conifers, cycads, ferns, and an increasing diversity of flowering plants that were relatively new on the evolutionary scene. The rich fossil record from formations like the Kaiparowits in Utah provides an exceptionally detailed window into these ancient ecosystems. Geological evidence suggests periodic flooding was common in these environments, which may explain why some Gryposaurus specimens are found in river channel deposits, possibly having been caught in sudden flood events that led to their preservation.

Evolutionary Relationships

Gryposaurus belongs to the Hadrosauridae family, specifically within the subfamily Saurolophinae (sometimes called Hadrosaurinae), which includes the flat-headed hadrosaurs as opposed to their hollow-crested lambeosaurine relatives. Phylogenetic analyses place Gryposaurus in a position relatively close to dinosaurs like Kritosaurus and Naashoibitosaurus, with which it shares certain cranial features. The evolutionary history of Gryposaurus reveals a successful radiation of species across western North America during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, spanning several million years. This temporal range makes the genus important for understanding hadrosaur evolution and diversification patterns. Some paleontologists have suggested that Gryposaurus may represent an ancestral morphotype that gave rise to later hadrosaurines, though the complex nature of hadrosaurid evolution continues to be refined with discoveries. The unique nasal arch of Gryposaurus represents a distinctive evolutionary pathway different from the elaborate hollow crests developed by lambeosaurine hadrosaurs, demonstrating alternative solutions to similar selective pressures for display structures or sensory functions.

Notable Fossil Discoveries

Several remarkable Gryposaurus specimens have significantly advanced our understanding of this genus since its initial discovery. The Kaiparowits Formation in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah, yielded an exceptionally well-preserved skull and partial skeleton of Gryposaurus monumentensis in 2002, providing unprecedented insights into this species’ anatomy. The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in Utah has produced important Gryposaurus material that contributes to our understanding of dinosaur taphonomy and preservation. In Montana, discoveries from the Two Medicine Formation include specimens of Gryposaurus latidens with distinctive dental adaptations. Perhaps most significant for understanding Gryposaurus’s soft tissue were discoveries that included skin impressions, revealing the texture and pattern of the dinosaur’s external covering. The Raymond M. Alf Museum in California houses a juvenile Gryposaurus specimen that provides valuable information about growth and development in these dinosaurs. Each of these discoveries has added pieces to the puzzle of Gryposaurus biology, gradually building a more comprehensive picture of this fascinating dinosaur’s life and evolution.

Modern Research and Ongoing Discoveries

Research on Gryposaurus continues to evolve with new technologies and methodologies expanding our understanding of this ancient animal. CT scanning of Gryposaurus skulls has allowed paleontologists to examine internal structures and brain cavities, providing insights into sensory capabilities and neural anatomy without damaging precious fossils. Stable isotope analyses of tooth material have begun to reveal details about diet and habitat, including seasonal variations in food sources. Biomechanical modeling using computer simulations has helped scientists understand how Gryposaurus moved, balanced, and processed food, contributing to more accurate reconstructions of its biology. Field work in the American Southwest continues to uncover new Gryposaurus material, with expeditions to less-explored areas of formations like the Kaiparowits promising future discoveries. The application of geometric morphometrics to compare subtle differences in bone shapes has helped refine species boundaries and evolutionary relationships within the genus. As paleontological methods continue to advance, our understanding of Gryposaurus and its place in Late Cretaceous ecosystems will undoubtedly become even more nuanced and complete.

Gryposaurus in Popular Culture and Museum Displays

Despite its distinctive appearance and scientific importance, Gryposaurus has maintained a relatively low profile in popular culture compared to more famous dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus or Triceratops. Nevertheless, impressive museum displays featuring Gryposaurus can be found at several major institutions, including the Natural History Museum of Utah, which showcases specimens from the local Kaiparowits Formation. The Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada, displays excellent Gryposaurus notabilis material from Dinosaur Provincial Park. Life-sized reconstructions and artistic renderings of Gryposaurus have become more scientifically accurate over time, incorporating evidence from skin impressions and improved understanding of muscle attachments. Educational programs at museums and national parks in the American Southwest often highlight Gryposaurus as an important component of the region’s prehistoric ecosystems. The dinosaur has appeared in several documentary series about prehistoric life, including programs focused specifically on the rich fossil beds of the American Southwest. As public interest in dinosaur diversity beyond the most famous species continues to grow, Gryposaurus’s unique appearance and significant role in Late Cretaceous ecosystems position it to receive greater recognition in popular presentations of prehistoric life.

Conclusion

Gryposaurus stands as a testament to the remarkable diversity of dinosaurs that once dominated terrestrial ecosystems. Its distinctive hook-nosed appearance, specialized feeding adaptations, and successful radiation across western North America reveal an animal perfectly adapted to the lush, subtropical environments of the Late Cretaceous Southwest. As research continues and new specimens emerge from the ancient sediments of Utah, Montana, and beyond, our understanding of this fascinating hadrosaur will continue to deepen. The story of Gryposaurus is more than just the tale of a single dinosaur genus—it’s a window into an entire lost world, a glimpse of North America as it existed 80 million years ago, when forests flourished where deserts now stand, and the distinctive silhouette of the hook-nosed lizard moved in herds across landscapes that would be unrecognizable today.