Have you ever watched a dinosaur movie and wondered whether those terrifying roars actually reflected reality? You’re not alone. For decades, filmmakers have crafted iconic soundscapes for these ancient beasts, yet scientists working with fossils can tell us something quite different. The truth is, reconstructing what dinosaurs actually sounded like presents a fascinating puzzle that combines paleontology, cutting-edge technology, and a bit of educated guesswork.

Let’s be honest here, there’s something deeply compelling about imagining the prehistoric world not just as silent stone but as a living, breathing, calling ecosystem. Recent discoveries have pushed us closer than ever to understanding these vanished voices, yet the journey is anything but straightforward.

The Challenge of Soft Tissue Preservation

You’re faced with a fundamental problem when trying to reconstruct dinosaur sounds: voice boxes are made of cartilage that doesn’t fossilize well. Think about it. Most of what creates sound in living animals involves soft tissues like vocal cords, membranes, and muscle structures that decompose long before mineralization can preserve them. This makes the task incredibly difficult.

While hyoids are sometimes preserved as fossils, no larynx had been reported in extinct non-avian reptiles until very recently, and this is probably because the larynx is cartilaginous in all tetrapods except neognath birds. The fossil record offers us bones, impressions, and occasionally mineralized remains, but rarely the delicate structures that actually produced sound. Still, paleontologists have found creative ways around this obstacle, and their methods are surprisingly ingenious.

CT Scanning: Peering Inside Ancient Skulls

The real breakthrough came with computed tomography scanning. Computer scientists and paleontologists used computed tomography (CT scans) and powerful computers, creating a three-dimensional computer model of the crest by performing a CT scan, with a series of about 350 cross sections taken of the skull and crest at 3mm intervals. Imagine being able to virtually slice through a 75-million-year-old fossil without damaging it.

The use of digital paleontology permitted a thorough analysis of the inside of the crest without having to physically cut through it, and thereby damaging it. This non-invasive technique has revolutionized how researchers study fossils. They can now reconstruct internal air passages, chambers, and structures that were completely hidden from view. What used to take months of painstaking physical preparation can now be accomplished digitally in far less time.

The Parasaurolophus Case Study

The study of dinosaur vocalization began after the discovery in August 1995 of a rare Parasaurolophus skull fossil measuring about 4.5 feet long. The dinosaur had a bony tubular crest that extended back from the top of its head. Many scientists have believed the crest, containing a labyrinth of air cavities and shaped something like a trombone, might have been used to produce distinctive sounds. This duck-billed dinosaur became the poster child for dinosaur sound reconstruction.

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Once the size and shape of the air passages were determined with the aid of powerful computers and unique software, it was possible to determine the natural frequency of the sound waves the dinosaur pumped out, much the same as the size and shape of a musical instrument governs its pitch and tone. The crest functioned essentially as a natural wind instrument. As expected, based on the structure of the crest, the dinosaur apparently emitted a resonating low-frequency rumbling sound that can change in pitch.

Comparing Modern Relatives: Birds and Crocodilians

Recent studies have approached the question of dinosaur vocalizations by comparing them to modern relatives: birds and crocodilians. Both share a common evolutionary lineage with dinosaurs, and both produce vocalizations in very different ways than mammals. This comparative approach gives researchers a framework for understanding what might have been possible.

Think about it this way. Scientists theorize that many dinosaurs may have produced closed-mouth vocalizations. These are lower and more percussive, as opposed to bird calls, which are more varied in pitch and almost melodic. Modern examples of closed-mouth vocalizations include crocodilian growls and ostrich booms. The iconic roaring T. rex from movies? Probably never happened. The assumption that dinosaurs roared with open mouths – like lions or bears – is, by contrast, an entirely mammalian construct.

Rare Fossilized Voice Boxes Reveal New Clues

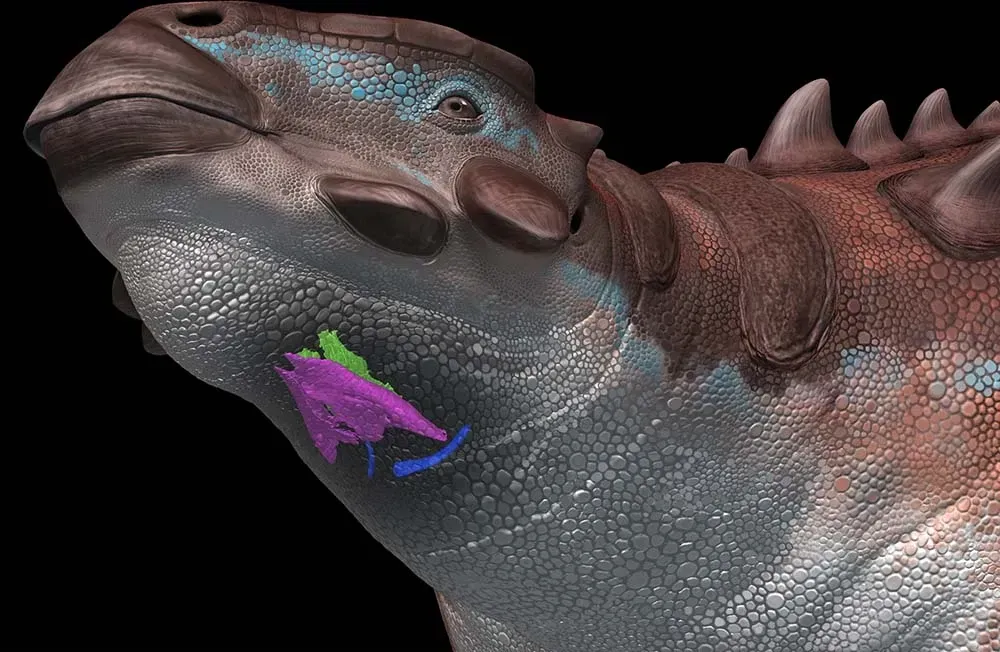

Then came an extraordinary discovery. The fossil larynx found in non-avian dinosaurs from ankylosaur Pinacosaurus grangeri was composed of the cricoid and arytenoid like non-avian reptiles, but specialized with the firm and kinetic cricoid-arytenoid joint, prominent arytenoid process, long arytenoid, and enlarged cricoid, as a possible vocal modifier like birds rather than vocal source like non-avian reptiles. This was only the first fossilized dinosaur voice box ever found.

Pulaosaurus is only the second known non-avian dinosaur with a bony voice box preserved. While the bony vocal organ of Pinacosaurus was not exactly like the syrinx of extant birds, its large and mobile anatomy may have nevertheless allowed the iconic armored dinosaur to make bird-like noises. These findings suggest that at least some dinosaurs had surprisingly sophisticated vocal capabilities, potentially producing sounds more complex than previously imagined.

Examining Ear Structure for Sound Range

You might wonder how researchers determine what sounds dinosaurs could actually hear. The structure of the ear and even the layout of the braincase can give scientists clues about the kinds of sounds an animal is capable of hearing. The thinking goes that any animal will adapt to hear sounds which are important to them, which include the vocalizations of their peers. It’s a clever bit of detective work.

Fossil records of the large bones in the dinosaur’s ears compared to corresponding bones in human ears suggests they were able to hear lower frequencies than humans. This tells us something crucial: if dinosaurs evolved ears optimized for low frequencies, they were probably producing low-frequency calls themselves. The anatomy doesn’t lie about function.

Creating Physical and Digital Models

Modern researchers haven’t stopped at computer simulations. A researcher studied CT scans of a young Corythosaurus skull. With the help of collaborators, she 3D-printed the crest and nasal passages, effectively reconstructing the dinosaur’s built-in sound system. Into this model, she added a mechanical larynx that vibrates when air is blown through a mouthpiece, similar to how a trumpet works. The result? A ghostly, otherworldly sound that could shift from whispers to booming calls depending on the breath.

More recently, Lin created a physical setup made of tubes to represent a mathematical model that will allow researchers to discover what was happening acoustically inside the Parasaurolophus crest. The physical model, inspired by resonance chambers, was suspended by cotton threads and excited by a small speaker, and a microphone was used to collect frequency data. While it isn’t a perfect replication of the Parasaurolophus, the pipes – nicknamed the “Linophone” – will serve as a verification of the mathematical framework.

What We Know – and What We Don’t

So what can we actually say with confidence? The resulting sound probably approximates the noises that the dinosaur crest could produce fairly well. But it is hard to say for certain. Researchers had to reconstruct missing parts such as the beak and nostrils, but also the soft tissues of the head and throat that were not fossilized. Since it’s uncertain whether the Parasaurolophus had vocal cords, a variation of sounds with and without vocal cords was simulated.

I think it’s important to acknowledge the limitations here. We’re working with incomplete information, making educated guesses based on structure, modern analogies, and physics. We’ll probably never know precisely what the prehistoric world sounded like. Yet what we’ve learned is remarkable. These weren’t silent creatures lumbering through primordial forests. They communicated, called to each other, warned of danger, and perhaps even sang in their own way.

Conclusion: Listening to Deep Time

Reconstructing dinosaur sounds from fossil evidence combines multiple scientific disciplines in ways that would have seemed impossible just decades ago. From CT scanning technology that reveals hidden internal structures to comparative anatomy studies with living relatives, researchers have pieced together an increasingly detailed picture of the prehistoric soundscape. While we may never hear a true dinosaur call, the approximations we’ve created through fossilized crests, voice boxes, and ear structures bring us closer than ever before.

The journey from silent stone to reconstructed sound represents one of paleontology’s most creative challenges. Each fossil discovery, each technological advance, adds another piece to this acoustic puzzle. Did these ancient creatures sound anything like what you imagined? The answer probably surprises you.