The story of dinosaurs is inextricably linked to Earth’s climate. For over 165 million years, these remarkable creatures dominated our planet, evolving through dramatic shifts in atmospheric conditions, continental arrangements, and ecological pressures. As paleoclimatology advances, scientists are uncovering fascinating connections between ancient climate patterns and dinosaur evolution. From their emergence in the Triassic to their abrupt extinction at the end of the Cretaceous (excluding avian dinosaurs), these animals adapted to wildly varying conditions that shaped their anatomy, distribution, and survival strategies. This article explores how Earth’s changing climate influenced dinosaur evolution, offering insights into one of the most successful animal dynasties in our planet’s history.

The Triassic Emergence: Hot and Dry Beginnings

The earliest dinosaurs evolved during the Late Triassic period, approximately 230 million years ago, in a world markedly different from our own. The supercontinent Pangaea dominated Earth’s geography, creating vast inland areas characterized by hot, arid conditions with strong seasonality. These challenging environments selected for animals with specific adaptations—early dinosaurs developed efficient, upright postures and potentially enhanced metabolic capabilities that gave them advantages over their more sprawling contemporaries. The semi-arid conditions of the Triassic likely contributed to the relatively small size of early dinosaurs like Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus, which were nimble predators adapted to catch fast-moving prey in open habitats. This initial phase of dinosaur evolution demonstrates how climate conditions can create selective pressures that favor certain body types and physiological adaptations.

The End-Triassic Extinction: Climate Catastrophe as Evolutionary Catalyst

Approximately 201 million years ago, a massive extinction event marked the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, eliminating up to 80% of all species on Earth. This catastrophe is linked to extensive volcanic activity that triggered rapid climate change, including global warming, ocean acidification, and potentially periods of extreme cold. While devastating for much of Earth’s biodiversity, this climate crisis paradoxically benefited dinosaurs by eliminating many of their ecological competitors. With the extinction of large crurotarsan archosaurs (relatives of crocodiles), dinosaurs were able to expand into vacant ecological niches, setting the stage for their Jurassic radiation. The End-Triassic extinction represents a clear example of how climate-driven mass extinctions can dramatically redirect evolutionary trajectories, turning ecological underdogs into dominant life forms.

Jurassic Climate Optimum: Rise of the Giants

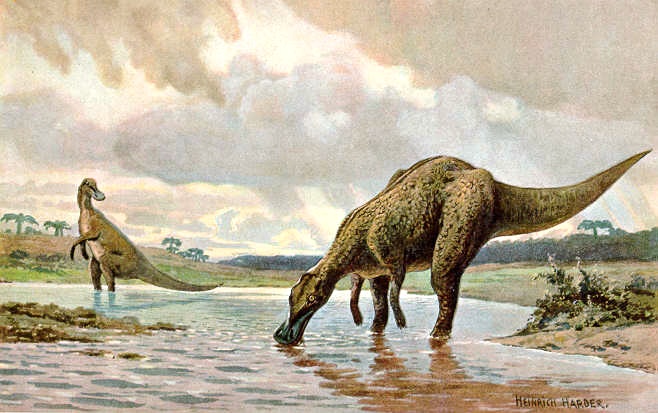

The Middle to Late Jurassic period (174-145 million years ago) witnessed a significant warming trend that transformed Earth’s ecosystems. Global temperatures rose, ice caps melted, and sea levels increased, creating warm, humid conditions across much of the planet. This climate optimum coincided with the evolution of truly gigantic sauropod dinosaurs like Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, and eventually Argentinosaurus. The expansion of lush gymnosperm forests provided abundant vegetation to support these massive herbivores, while the warm, stable climate allowed for extended growing seasons and greater primary productivity. Paleontologists have suggested that elevated atmospheric oxygen levels and carbon dioxide concentrations during this period may have supported both the growth of massive plant matter and the evolution of large body sizes in sauropods. The Jurassic climate optimum illustrates how favorable climate conditions can push the boundaries of biological possibility.

Continental Drift and Climate Zones: Diversification Through Isolation

Throughout the Mesozoic Era, the breakup of Pangaea created increasingly isolated landmasses with distinct climate regimes, driving dinosaur diversification through geographical isolation. By the Late Jurassic, the supercontinent had begun fragmenting into Laurasia (north) and Gondwana (south), with the formation of the Central Atlantic Ocean between them. This separation created opportunities for allopatric speciation—the evolution of new species due to geographical barriers. Different climate zones emerged across these separating landmasses, from tropical equatorial regions to more temperate high-latitude environments. The isolation of dinosaur populations in these distinct climate regions led to remarkable adaptations, such as the potentially cold-adapted polar dinosaurs found in Australia and Antarctica, which evolved to survive in dark winter conditions near the ancient South Pole. Continental drift and the resulting climate zonation thus served as a powerful engine for dinosaur diversification.

The Cretaceous Thermal Maximum: Evolutionary Innovation in Peak Heat

The mid-Cretaceous period (approximately 95 million years ago) represents one of the warmest intervals in Earth’s Phanerozoic history, with global average temperatures estimated to be 6-14°C higher than present day. This extreme greenhouse climate was characterized by high atmospheric CO₂ levels, reduced temperature gradients between the equator and poles, and significantly elevated sea levels that created vast inland seas. Dinosaur evolution accelerated during this thermal maximum, with remarkable diversification occurring across major lineages. The fossil record shows an explosion of new body plans, particularly among horned dinosaurs (ceratopsians), duck-billed dinosaurs (hadrosaurs), and specialized theropods. Ecological opportunities expanded as flowering plants (angiosperms) diversified rapidly under these warm conditions, creating new plant-herbivore relationships. The Cretaceous thermal maximum demonstrates how periods of extreme climate can paradoxically stimulate biological innovation rather than limiting it.

Polar Dinosaurs: Adaptations to Seasonal Extremes

One of the most remarkable discoveries in paleontology has been the abundance of dinosaur fossils in ancient polar regions, including Alaska, Australia, and Antarctica. Despite warmer global temperatures during the Mesozoic, these high-latitude environments still experienced months of darkness and seasonal temperature fluctuations. Dinosaurs living in these regions developed specialized adaptations to cope with these challenging conditions. Studies of dinosaur remains from Alaska’s North Slope reveal evidence of possible insulating structures in some species, while bone microstructure analyses suggest many polar dinosaurs had accelerated growth rates to capitalize on brief productive seasons. Some polar dinosaur communities appear to have been year-round residents rather than seasonal migrants, based on the presence of juvenile specimens and nesting sites. The success of dinosaurs in polar environments underscores their remarkable climatic adaptability and challenges earlier views that they were strictly warm-climate specialists.

The Mid-Cretaceous Dinosaur Migrations: Climate-Driven Movements

The continuing fragmentation of continents during the Cretaceous period created complex patterns of dinosaur dispersal and isolation, often driven by climate changes. As North America and Europe separated further, distinctive dinosaur faunas evolved on each continent, adapted to their particular climate regimes. However, intermittent land bridges formed during periods of lower sea levels, allowing dinosaur migrations between previously isolated regions. These climate-driven connections led to fascinating biogeographical patterns visible in the fossil record. For instance, similar tyrannosaur species appear in both Asia and western North America during certain intervals, suggesting climate-enabled migration events. The relationship between changing sea levels (controlled by climate) and dinosaur distribution patterns shows how climate fluctuations could periodically reconnect isolated populations, creating complex evolutionary patterns over millions of years.

Feathered Dinosaurs and Climate Insulation

The discovery of extensively feathered non-avian dinosaurs, particularly among theropods from China’s Liaoning Province, has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur physiology and climate adaptation. These exquisitely preserved fossils from the Early Cretaceous reveal that many dinosaur lineages possessed complex feather-like structures long before the evolution of flight. The development of these integumentary structures likely began as adaptations for insulation in variable climate conditions. Early feather-like filaments would have helped regulate body temperature, providing insulation in cooler environments while potentially being shed or reduced in warmer seasons. The evolutionary refinement of these structures eventually enabled other functions, including display and, ultimately, flight in avian dinosaurs. The presence of insulating structures across multiple dinosaur lineages suggests that climate regulation was a significant selective pressure throughout dinosaur evolution.

Dinosaur Metabolism and Climate Adaptation

The relationship between dinosaur physiology and climate remains one of the most debated topics in paleontology. Growing evidence suggests that many dinosaur groups maintained elevated metabolic rates compared to modern reptiles, allowing them to thrive across diverse climate zones. Bone histology studies reveal that most dinosaurs possessed rapid growth rates more similar to birds and mammals than to modern reptiles, indicating higher metabolic activity. This elevated metabolism would have provided greater independence from environmental temperatures, enabling dinosaurs to inhabit regions with seasonal temperature fluctuations. However, different dinosaur lineages likely evolved varying metabolic strategies in response to specific climate challenges. Large sauropods may have used gigantothermy—thermal stability through sheer body mass—while small theropods potentially relied on higher metabolic rates and insulation. These varied physiological adaptations demonstrate how climate pressures drove the evolution of diverse metabolic solutions across Dinosauria.

Late Cretaceous Climate Cooling: Preparing for the End

The final 10 million years of the Cretaceous period witnessed a significant global cooling trend that placed new pressures on dinosaur communities. Average global temperatures declined by several degrees, sea levels began to retreat, and seasonality increased across many regions. This climate shift coincided with important changes in dinosaur communities, including the diversification of specialized herbivore groups like the ceratopsians and hadrosaurs with their advanced dental batteries for processing tougher vegetation. Some paleontologists suggest that the cooling climate may have reduced primary productivity in certain regions, intensifying competition among large herbivores and driving the evolution of more efficient feeding structures. Predatory dinosaurs similarly developed more specialized adaptations, with tyrannosaurs evolving into hypercarnivorous giants with massive skulls and powerful bites. These late Cretaceous adaptations reveal how cooling climate conditions continued to shape dinosaur evolution even in their final chapter.

Microhabitats and Local Climate Adaptations

Beyond broad global climate patterns, dinosaurs evolved remarkable adaptations to local microhabitats and regional climate variations. Fossil evidence from the Hell Creek Formation in North America shows how different dinosaur species occupied specific environmental niches within the same general region based on subtle climate and habitat differences. Triceratops appears more abundant in drier, more inland habitats, while Edmontosaurus fossils concentrate in wetter, more coastal environments. Skull morphology in some hadrosaur species suggests adaptations for different vegetation types associated with specific climate-influenced habitats. The diversity of cranial crests, frills, and ornaments across dinosaur species may have evolved partly for species recognition within these varied microclimates. These fine-scale adaptations demonstrate that dinosaur evolution responded not just to global climate trends but also to local environmental variations created by topography, proximity to water, and regional weather patterns.

The K-Pg Extinction: Climate Catastrophe Ends an Era

The most dramatic climate impact on dinosaur evolution came 66 million years ago when an asteroid struck Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, triggering the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) mass extinction. This impact unleashed a cascade of climate catastrophes, including global wildfires, acid rain, and a prolonged “impact winter” caused by sun-blocking atmospheric debris. Surface temperatures may have dropped by 10°C or more for years following the impact, dramatically reducing photosynthesis and collapsing food webs. This climate disaster proved insurmountable for non-avian dinosaurs, ending their 165-million-year evolutionary journey. Importantly, not all dinosaurs perished—avian dinosaurs (birds) survived the extinction, potentially due to adaptations including smaller body sizes, efficient metabolism, and dietary flexibility that helped them weather the climate crisis. The survival of birds through this extreme climate event represents both an end and a continuation of the relationship between climate and dinosaur evolution.

Conclusion

The evolutionary journey of dinosaurs was profoundly shaped by Earth’s changing climate. From their origins in the hot, arid Triassic to their diverse adaptations in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, dinosaurs repeatedly demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability to shifting climate conditions. Their evolutionary responses—including changes in body size, insulation, metabolism, and ecological specialization—allowed them to thrive across a remarkable range of environments and through multiple climate transitions. While a climate catastrophe ultimately ended the reign of non-avian dinosaurs, their avian descendants continue to demonstrate this evolutionary adaptability today. Understanding the relationship between climate and dinosaur evolution not only illuminates our planet’s past but may offer insights into how modern species might respond to our current climate crisis. The dinosaur story reminds us that the climate has always been a powerful force in evolutionary history, driving both innovation and extinction.