In the rugged outcrops of ancient rock formations and along weathered hiking trails, an unexpected partnership has been flourishing. Professional paleontologists, once working primarily within academic institutions, are now joining forces with everyday nature enthusiasts to uncover the secrets of Earth’s distant past. This collaboration between scientists and citizen volunteers represents a remarkable shift in how fossil discoveries are made. Hikers with keen eyes and curious minds are increasingly becoming the front-line scouts in paleontological research, spotting specimens that might otherwise remain hidden for millions more years. The democratization of fossil hunting has expanded our understanding of prehistoric life while creating meaningful connections between ordinary citizens and the scientific community. Let’s explore how this fascinating partnership works and why it has become so valuable to modern paleontology.

The Democratization of Fossil Hunting

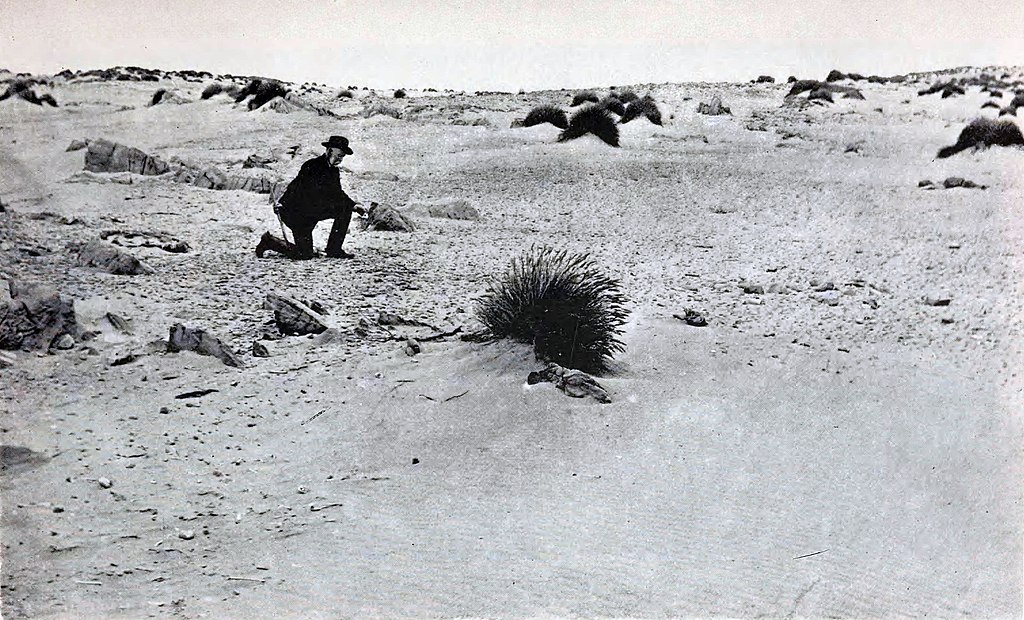

Paleontology has undergone a significant transformation in recent decades, evolving from a field dominated exclusively by academic professionals to one that increasingly welcomes contributions from the public. This shift represents more than just a change in who makes discoveries; it reflects a fundamental democratization of scientific exploration. Amateur fossil hunters, often equipped with nothing more than observant eyes and basic knowledge, now regularly make significant discoveries that expand our understanding of prehistoric life. Many professional paleontologists have embraced this change, recognizing that more observers in the field exponentially increase the chances of important finds. Organizations like the Paleontological Society now offer resources specifically designed for citizen scientists, guiding identification, documentation, and proper reporting procedures. This inclusive approach has breathed new life into the discipline while making science more accessible to everyday people with a passion for natural history.

The Advantage of Numbers: Why Citizen Scientists Matter

The sheer numerical advantage that citizen scientists bring to paleontology cannot be overstated. Professional paleontologists, despite their expertise and dedication, are limited in number—perhaps only a few thousand worldwide focus specifically on fossil research. In contrast, millions of hikers, nature enthusiasts, and outdoor adventurers regularly traverse the same landscapes where fossils might be exposed. This massive multiplication of observant eyes on the ground creates an unofficial surveillance network that can spot newly eroded or exposed specimens across vast geographical areas. The mathematics is compelling: even if only a tiny percentage of hikers know what to look for, their collective coverage far exceeds what the professional community could achieve alone. This advantage becomes even more significant in remote or less-studied regions where formal expeditions are rare but recreational hikers still venture. The combination of wide geographical coverage and frequency of visits means citizen scientists often discover fossils shortly after natural erosion reveals them, before they can be damaged by weather or other factors.

Technological Tools Empowering Citizen Paleontologists

The rise of accessible technology has dramatically enhanced the capabilities of citizen fossil hunters. Smartphone apps designed specifically for fossil identification, such as Fossil Finder and myFOSSIL, now provide instant guidance to amateurs who might otherwise pass by significant specimens without recognition. These applications often include visual databases, location logging capabilities, and direct connections to experts who can verify. High-quality digital photography, once the domain of professionals, is now available to anyone with a smartphone, allowing detailed documentation of finds without disturbing the specimen. GPS technology enables precise location recording, critical for establishing the geological context of discoveries. Online communities and social media groups dedicated to amateur paleontology create supportive networks where knowledge is shared and identification assistance is readily available. This technological toolkit has effectively lowered the barrier to meaningful participation in paleontological research, enabling even novice fossil enthusiasts to make scientifically valuable contributions while following ethical collection guidelines.

Notable Discoveries by Everyday Explorers

The history of paleontology is increasingly punctuated by remarkable discoveries made by non-professionals. In 2020, 4-year-old Lily Wilder spotted a perfectly preserved 215-million-year-old dinosaur footprint while walking on a beach in Wales, a find that experts later confirmed as one of the best-preserved examples from that period in the region. Canadian hiker Jared Voris discovered a new species of tyrannosaur while hiking in Alberta in 2018, now named Thanatotheristes degrootorum, representing the first new tyrannosaur species found in Canada in 50 years. In Montana, volunteer fossil hunter Jason Love uncovered the skull of a previously unknown species of elasmosaur during a recreational expedition with the Burke Museum, leading to significant new understanding of marine reptile diversity in the Western Interior Seaway. Perhaps most famously, Mary Anning, though working before the modern concept of citizen science, was essentially an amateur who made some of paleontology’s most important discoveries in the early 19th century, including the first correctly identified ichthyosaur skeleton. These examples demonstrate that groundbreaking discoveries are not the exclusive domain of professionals with advanced degrees but can come from anyone with observant eyes and a passion for the past.

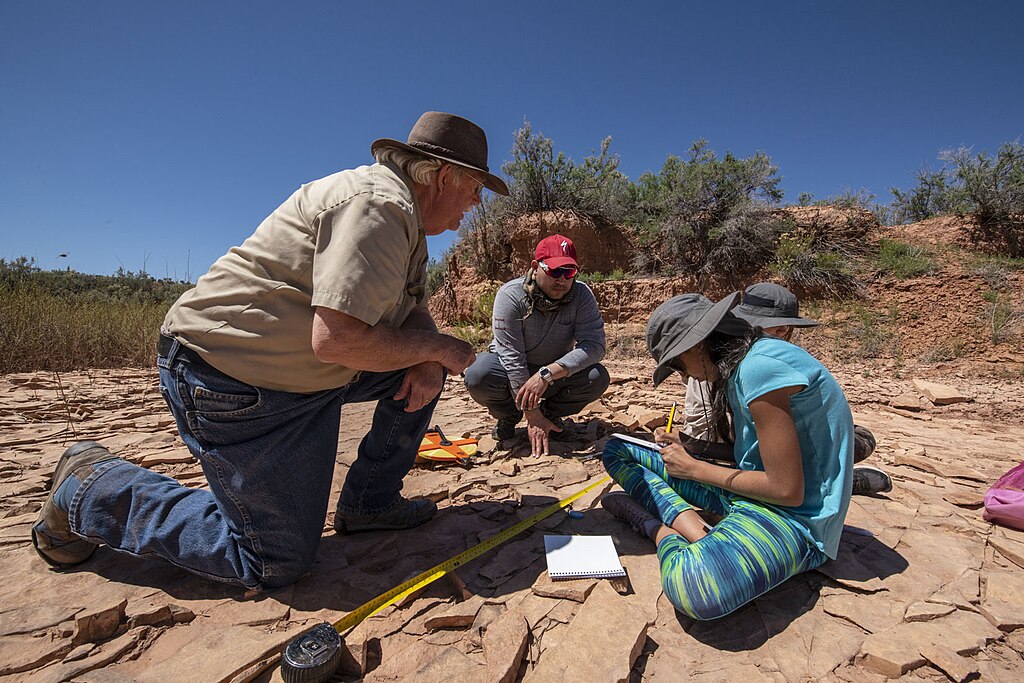

Formal Citizen Science Programs in Paleontology

Recognizing the value of public participation, many museums and research institutions have established structured programs specifically designed to harness the potential of citizen scientists. The Natural History Museum of Utah’s “Paleontology Citizen Science” program trains volunteers in proper fossil identification, documentation techniques, and ethical collection practices before sending them to monitor specific areas with paleontological potential. The Mammoth Site in Hot Springs, South Dakota, operates an “Earthwatch” program where participants contribute directly to ongoing excavations under professional supervision, learning hands-on techniques while adding to the scientific dataset. The Dinosaur Tracking Project at the University of Colorado Denver employs citizen scientists to document footprints and trace fossils across the American West, building a comprehensive database that would be impossible for the professional staff alone to compile. The PaleoBlitz events organized by the Paleontological Society bring together professionals and amateurs for intensive, collaborative fossil surveys of specific regions, resulting in multiple new locality discoveries annually. These formalized programs provide structure and scientific rigor to citizen contributions while creating rewarding experiences that deepen participants’ connection to paleontological science.

The Crucial Role of Hiking Clubs and Outdoor Organizations

Hiking clubs and outdoor recreation organizations have emerged as unexpected yet vital allies in paleontological research. Groups like the Appalachian Mountain Club and the Sierra Club now frequently incorporate basic fossil identification training into their leadership programs, creating informed guides who can recognize potential specimens during regular excursions. Many regional hiking organizations have established partnerships with local museums or university geology departments, creating clear protocols for when members encounter possible fossils during their activities. The American Hiking Society has developed specific ethical guidelines for hikers who encounter fossils, emphasizing documentation rather than collection in most circumstances. These organizations’ regular trail maintenance activities occasionally expose fossil-bearing layers, with trained members able to recognize and report significant finds before they would naturally erode into view. The extensive networks maintained by these groups effectively create corridors of informed observers across vast landscapes, particularly valuable in areas that might not otherwise receive scientific attention. Through these collaborative relationships, weekend recreational activities are transformed into meaningful contributions to scientific knowledge.

Ethical Considerations and Best Practices

The integration of citizen scientists into paleontological research necessitates clear ethical guidelines to ensure that enthusiastic participation doesn’t inadvertently damage the scientific record. The “take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints” ethos has been adapted specifically for fossil encounters, with emphasis on photographic documentation rather than collection in most circumstances. Professional organizations like the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology have developed specific guidelines for citizen scientists, clarifying when collection might be appropriate (such as in cases of imminent destruction) versus when in-situ documentation is preferable. Education about the legal frameworks governing fossil collection on different land types—private, state, federal, or tribal—is crucial, as regulations vary dramatically between these jurisdictions. Proper documentation protocols have been simplified for citizen scientists, focusing on the essential data: precise location, geological context, photographs from multiple angles with scale references, and careful recording of associated materials. The emphasis on collaboration rather than independent action helps ensure that potentially significant discoveries receive appropriate scientific attention while preserving crucial contextual information that might be lost through improper collection techniques.

Training the Citizen Paleontologist

Effective participation in paleontological citizen science requires some basic training, which has become increasingly accessible through various channels. Many natural history museums now offer weekend workshops specifically designed to train hikers and outdoor enthusiasts in fossil recognition, focusing on the types of fossils most common in their local regions. Online courses through platforms like Coursera and edX provide foundational knowledge in paleontology that was previously available only through university enrollment. Field guides designed specifically for amateur fossil hunters have proliferated, with region-specific versions helping citizens identify what might be significant in their particular area. Annual fossil hunting excursions led by professionals serve as hands-on training opportunities where amateurs can develop their search image and learn proper documentation techniques directly from experts. Community college geology departments increasingly offer non-credit courses specifically targeted at recreational fossil enthusiasts, providing systematic knowledge without the commitment of a degree program. This multi-faceted educational ecosystem has created multiple pathways for citizens to acquire the knowledge necessary to make meaningful contributions, regardless of their prior scientific background.

The Psychology of Fossil Hunting

The psychological appeal of fossil hunting helps explain why citizen science initiatives in paleontology have been so successful at recruiting and retaining volunteers. The thrill of potentially being the first human to ever see a particular organism that lived millions of years ago creates a powerful sense of discovery and connection to deep time. For many participants, fossil hunting combines the physical benefits of hiking with the intellectual engagement of scientific observation, creating a uniquely satisfying form of outdoor recreation. The tangible nature of paleontological discoveries provides immediate gratification, unlike many other sciences where results might be abstract or require complex analysis to appreciate. Many citizen paleontologists report that their participation gives them a sense of contributing to knowledge that will outlast their lifetimes, creating a legacy through scientific contributions. Psychologists have noted that fossil hunting activates reward centers in the brain similar to other forms of “treasure hunting,” but with the added benefit of scientific significance and educational value. This powerful psychological appeal helps explain why many individuals who begin as casual participants often develop lifelong commitments to paleontological citizen science.

Digital Platforms Connecting Citizens and Scientists

Digital platforms have revolutionized how citizen paleontologists connect with the professional scientific community, creating unprecedented opportunities for collaboration across traditional boundaries. The myFOSSIL platform, developed with National Science Foundation funding, allows amateurs to upload images of potential fossils and receive identification assistance from experts, while simultaneously building a searchable database of citizen discoveries. Social media groups dedicated to fossil identification, some with tens of thousands of members, provide rapid community feedback when hikers encounter potential specimens during their outdoor activities. The iNaturalist platform, though primarily focused on living organisms, has expanded to include paleontological observations, with its artificial intelligence capabilities increasingly able to assist with preliminary fossil identifications. Virtual conferences and webinars specifically designed for the citizen paleontology community have proliferated, especially since 2020, making expert knowledge accessible regardless of geographical location. These digital ecosystems create communities of practice where knowledge flows bidirectionally between professionals and amateurs, with technological platforms serving as the connective tissue that makes meaningful collaboration possible across vast geographical distances.

Case Study: The Green River Formation Citizen Project

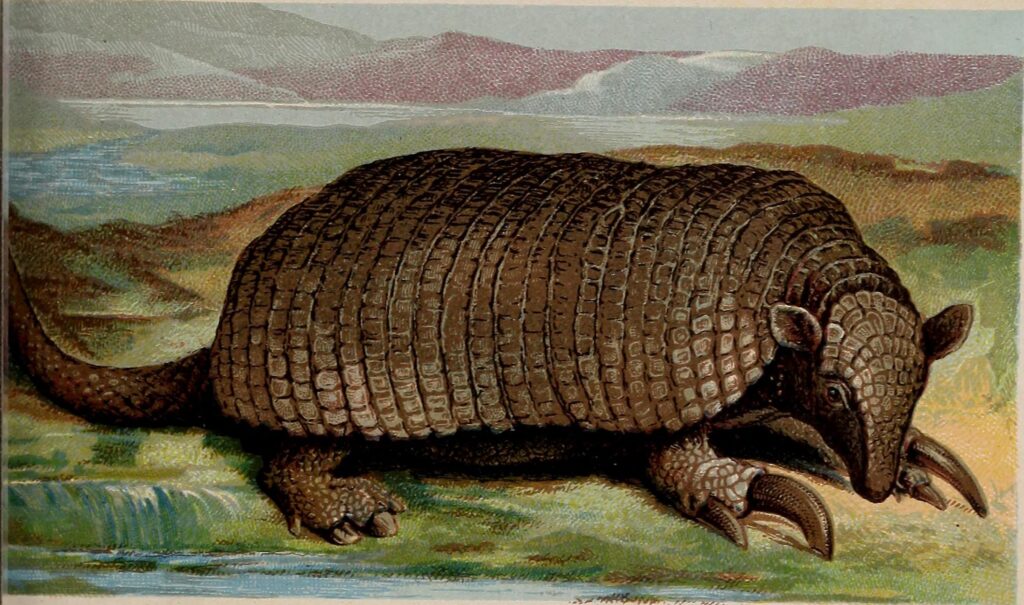

The Green River Formation project represents one of the most successful examples of citizen science in paleontology, demonstrating the potential when professional guidance meets enthusiastic public participation. Spanning parts of Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah, this fossil-rich formation preserves an extraordinary Eocene ecosystem approximately 50 million years old. The project began in 2012 when researchers from the University of Colorado recognized they lacked the personnel to adequately survey the vast exposure area. After developing a smartphone application with visual identification guides specific to Green River fossils, they recruited hiking clubs and outdoor recreation groups throughout the region. Participants received basic training in fossil identification, focusing on the distinctive characteristics of Green River fish, plants, and insects. Over the subsequent decade, citizen scientists documented more than 3,000 previously unrecorded fossil localities, including several containing rare specimens that have led to new species descriptions. Particularly significant was the 2017 discovery by retired postal worker Michael Stringer of an extraordinarily preserved bat fossil showing soft tissue impressions, now considered one of the most important mammal fossils from the formation. The project demonstrates how structured citizen involvement can dramatically accelerate the pace of discovery while creating meaningful scientific engagement for non-professionals.

Overcoming Skepticism in the Scientific Community

Despite its demonstrable successes, citizen science in paleontology initially faced significant skepticism from some corners of the academic establishment. Concerns about data quality, proper documentation, and potential damage to specimens led some professional paleontologists to view amateur contributions with caution. This skepticism has gradually diminished as citizen discoveries have repeatedly proven their scientific value, with many now published in peer-reviewed journals. The development of standardized protocols specifically designed for citizen scientists has addressed many quality control concerns, ensuring that even non-professional observations meet basic scientific standards. Technology has played a crucial role in overcoming skepticism, with digital photography and GPS coordinates providing verification that was previously difficult to obtain from amateur reports. Several prominent paleontologists who initially expressed reservations have become vocal advocates after experiencing firsthand the quality and significance of citizen contributions to their research areas. The integration of citizen science data into formal databases and collections has further legitimized these contributions, with many natural history museums now maintaining specific collections of citizen-discovered specimens that meet rigorous documentation standards.

The Future of Citizen Paleontology

The trajectory of citizen involvement in paleontology points toward an increasingly integrated future where the boundaries between professional and amateur contributions continue to blur. Emerging technologies like portable XRF (X-ray fluorescence) devices are becoming affordable enough for serious citizen scientists to conduct elemental analysis in the field, providing data previously available only in laboratory settings. Artificial intelligence applications specifically trained on fossil images are improving rapidly, with some systems already approaching expert-level accuracy in preliminary identifications of common fossil types. Community science hubs dedicated to paleontology are emerging in fossil-rich regions, creating physical spaces where citizens and professionals can collaborate on preparation, analysis, and research. Educational institutions are increasingly recognizing the value of paleontological citizen science, with some high schools and colleges incorporating it into their curriculum as experiential learning. As climate change and development accelerate erosion in many fossil-bearing formations, the distributed observation network of citizen scientists becomes increasingly valuable for identifying specimens that might otherwise be lost to science. This collaborative model of discovery, combining professional expertise with citizen enthusiasm and observational coverage, may represent the most effective approach to understanding Earth’s paleontological heritage before it disappears.

Conclusion

The partnership between professional paleontologists and citizen scientists represents one of science’s most successful collaborative models. As hiking trails crisscross fossil-bearing formations worldwide, ordinary nature enthusiasts equipped with basic knowledge and smartphone technology have become the eyes and ears of paleontological research. Their contributions—from discovering new species to documenting changing fossil distributions—have fundamentally enhanced our understanding of prehistoric life. This democratization of discovery has not only accelerated scientific progress but has created meaningful connections between people and the ancient history beneath their feet. As this partnership continues to evolve through better training, technology, and institutional support, the ancient past becomes not just the domain of specialists but a shared heritage that anyone with curiosity and observant eyes can help unveil. In the eroding outcrops and weathered hillsides of our planet, the next significant discovery might well be made not by a PhD researcher but by a hiker who paused to look closely at something unusual along the trail.