When you think about the age of dinosaurs, you might picture towering reptiles ruling every corner of the planet. Giant sauropods munching on treetops. Vicious theropods hunting in packs. Yet beneath this spectacle of prehistoric giants, small furry creatures were quietly going about their lives. These were our mammalian ancestors, and their survival story is far more fascinating than you might expect.

For over one hundred million years, mammals existed in a world dominated by creatures that could crush them in a single bite. They didn’t just survive, though. They thrived in ways that set the stage for everything from whales to humans. Let’s dive into the incredible survival strategies these resourceful animals used to outlast the age of giants.

Timing Was Everything: Arriving Just as Early as the Dinosaurs

Here’s something that might surprise you. Mammals appeared in the fossil record not long after dinosaurs, during the Late Triassic period. Both groups emerged at about the same time in the fossil record, so it wasn’t a case of dinosaurs already owning the planet before mammals showed up.

Think about that for a moment. From the very beginning, these two groups were neighbors. The first dinosaurs appeared slightly earlier than 230 million years ago, closely followed by the first mammals only a few million years later. Instead of fighting for the same space, however, each group carved out entirely different lifestyles that allowed them to coexist without stepping on each other’s toes, so to speak.

The Night Shift: Embracing a Nocturnal Lifestyle

Let’s be real. If you’re a small, furry creature living among giants that could eat you for breakfast, you’d probably want to avoid them, right? Early mammaliaforms developed a superior sense of smell backed by large brains, which facilitated entry into nocturnal niches with less exposure to archosaur predation.

Research on fur color from ancient mammal fossils supports this nocturnal theory. Mesozoic mammals were clad in dark brown or grayish fur, patterns consistent with animals that operate under the cover of darkness. The ancestor of mammals was nocturnal, and partial diurnal activity appeared among mammals only about 200,000 years after the meteorite impact that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. The darkness became their safe haven for millions upon millions of years.

Staying Small: The Power of Miniaturization

Size matters, especially when you’re trying not to be noticed. Most mammals that lived alongside dinosaurs were less than 100 grams in body mass, smaller than any non-bird dinosaur. Imagine something tinier than a modern-day mouse scurrying around the feet of creatures weighing several tons.

From the first appearance in rocks of Late Triassic times through 145 million years, these animals remained small, with the great majority being the size of shrews, rats, and mice. Honestly, staying small was a brilliant survival tactic. Smaller animals need less food, can hide more easily, and reproduce faster. A few exceptional species reached the size of foxes or beavers, yet these were rare exceptions rather than the rule.

Diverse Diets and Specialized Teeth: Eating to Survive

A very important change early on was developing teeth which occlude, or fit together to slice food efficiently. This adaptation gave mammals incredible flexibility in what they could eat. Dinosaurs typically had one type of tooth throughout their mouths, suited for either tearing meat or grinding plants.

Mammals, though? They evolved complex dental arrangements that allowed them to process a variety of foods efficiently. Some munched on insects. Others tackled tougher plant material. Mammal jaw disparity rose sharply during the Mesozoic before the impact, showing increased variety of herbivores, carnivores, omnivores and insectivores. This dietary diversity meant mammals weren’t competing with each other for the same limited resources, which helped them spread into multiple ecological niches.

Taking to Water, Air, and Underground: Ecological Innovation

Who says mammals during the dinosaur era were boring little insect-eaters? Ancient mammals evolved a wide variety of adaptations allowing them to exploit the skies, rivers and underground lairs. Some became accomplished swimmers, others glided between trees, and a few became expert diggers.

Castorocauda, from the middle Jurassic about 164 million years ago, had a beaver-like tail adapted for swimming, limbs adapted for swimming and digging, and teeth adapted for eating fish. Maiopatagium furculiferum had a membrane that acted like a gliding wing, showing it was one of the first flying mammals, probably gliding to access food high off the ground and to avoid being prey. These weren’t passive victims hiding in the shadows. They were ecological innovators exploring every available opportunity.

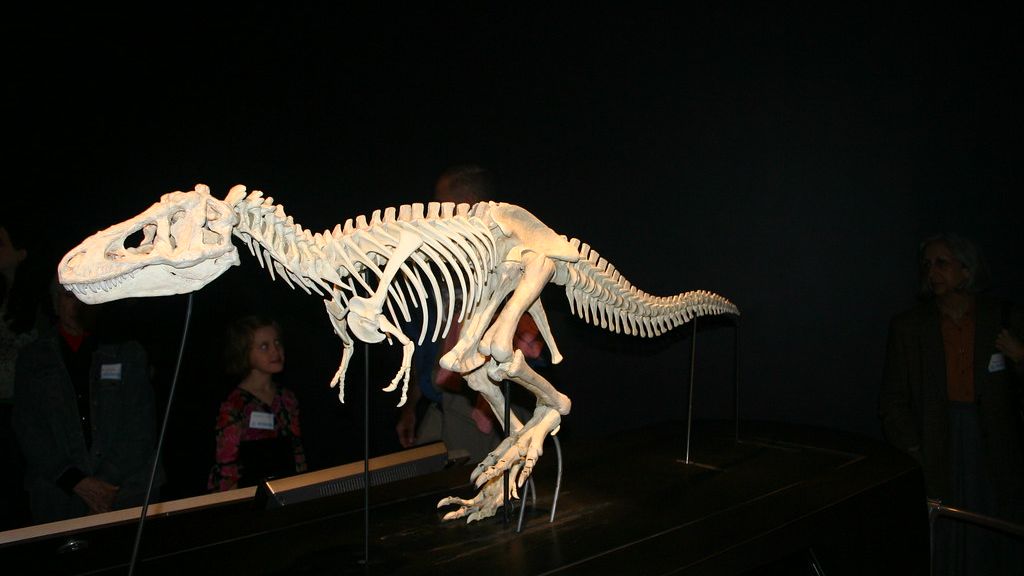

The Unexpected Predators: Some Mammals Ate Dinosaurs

Now here’s where things get really interesting. Not all mammals were timid little critters cowering from dinosaurs. Repenomamus robustus is one of several Mesozoic mammals for which there is good evidence that it fed on vertebrates, including dinosaurs, with evidence present in fossilized remains showcasing what was most likely a predation attempt directed at a specimen of Psittacosaurus.

Repenomamus giganticus had a body length of 68.2 centimeters and an estimated mass of 12 to 14 kilograms, making it roughly the size of a modern badger. Repenomamus was larger than several small sympatric dromaeosaurid dinosaurs like Graciliraptor. The tables had turned, at least occasionally. Some mammals weren’t just surviving alongside dinosaurs; they were hunting them.

Competition Among Mammals: A Hidden Battle

For decades, scientists assumed dinosaurs were the main obstacle preventing mammals from growing larger and more diverse. Recent research tells a different story. New methods to analyze mammal fossils revealed that it was not dinosaurs, but possibly other mammals, that were the main competitors of modern mammals before and after the mass extinction of dinosaurs.

While their relatives were exploring larger body sizes, different diets, and novel ways of life such as climbing and gliding, they were excluding modern mammals from these lifestyles, keeping them small and generalist in their habits. This finding changes everything we thought we knew. Mammals were holding each other back, competing for the same limited resources while dinosaurs dominated different ecological zones entirely. It’s hard to say for sure, but this competition may have actually shaped mammalian evolution more profoundly than dinosaur predation ever did.

After the Asteroid: The Final Chapter of Survival

A large meteor smashed into Earth 66 million years ago, creating the Chicxulub Crater in an event in which 75 percent of life became extinct, including all non-avian dinosaurs. The mammals that survived weren’t necessarily the biggest or strongest. Small mammals managed to survive while larger ancient mammals perished.

Immediately after the extinction, the biggest mammals were about rat-sized, but within 100,000 years there were raccoon-sized mammals, and by the 300,000-year mark, the biggest mammals were about the size of large beavers. The age of dinosaurs had ended, but the age of mammals was just beginning. Those survival strategies developed over millions of years, staying small, being nocturnal, eating diverse foods, finally paid off in ways no one could have predicted.

Conclusion

Prehistoric mammals didn’t just luck into survival. They adapted, innovated, and persisted through over one hundred million years of living in a dinosaur-dominated world. From embracing the night to developing specialized teeth, from taking to the water and air to occasionally turning the tables and hunting small dinosaurs themselves, these resourceful creatures wrote a survival story for the ages.

Their legacy lives on in every mammal alive today, from the tiniest shrew to the largest whale, and yes, even in us. The next time you see a mouse scurrying across your path or watch a bat swoop through the twilight, remember their ancestors survived an era of giants. What do you think was their most impressive adaptation? The answer might surprise you more than you expect.