The Ice Age represents one of Earth’s most dramatic environmental upheavals, fundamentally transforming life on our planet in ways that still echo today. Picture a world where giant creatures roamed vast frozen landscapes, where ecosystems operated under entirely different rules, and where survival meant evolving entirely new ways of living.

This wasn’t just about getting colder. The ice ages reshaped continents, created new habitats, and forced countless species into an evolutionary arms race against time and climate. The story of how global fauna responded to these massive changes reveals nature’s incredible ability to adapt and survive under the most extreme conditions. Let’s explore this fascinating chapter of Earth’s history and discover how these ancient climate shifts created the animal world we know today.

The Great Megafauna Catastrophe

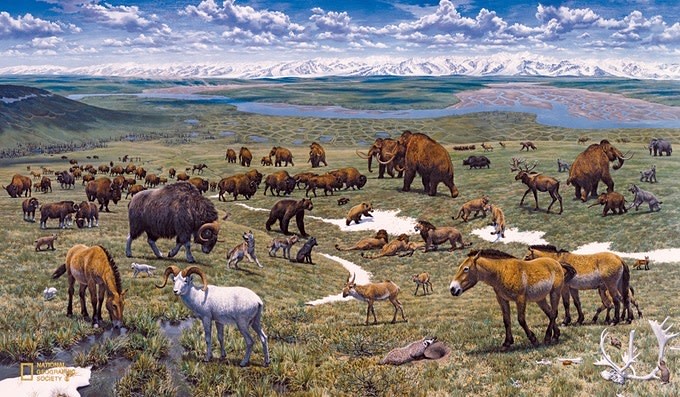

The end of the ice age marked one of the most devastating extinction events in Earth’s recent history. The Late Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene saw the extinction of the majority of the world’s megafauna, typically defined as animal species having body masses over 44 kg (97 lb), which resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity across the globe.

Some 65% of terrestrial megafauna genera (animals weighing >45 kg) became globally extinct during this period. Think about that for a moment: roughly two thirds of all large land animals simply vanished from Earth. This wasn’t a gradual decline but rather a rapid collapse that transformed entire ecosystems.

The extinctions during the Late Pleistocene are differentiated from previous extinctions by their extreme size bias towards large animals (with small animals being largely unaffected), and widespread absence of ecological succession to replace these extinct megafaunal species. The world lost its giants, and nothing comparable has taken their place since.

Among the casualties were woolly mammoths, giant ground sloths, saber-toothed cats, and massive short-faced bears. The end of the Pleistocene in North America saw the extinction of 38 genera of mostly large mammals. The scale was breathtaking and the consequences permanent.

Arctic Survivors: The Success Stories

Not all species succumbed to the ice age transformation. Some animals not only survived but actually thrived under the harsh conditions. Steppe bison, horse, and woolly mammoth became extinct, moose and humans invaded, while muskox and caribou persisted.

There were species that are still alive today including muskox (Ovibos moschatus), caribou (Rangifer tarandus), mountain sheep (Ovis dalli and nivicola), saiga (Saiga tatarica), brown bears (Ursus arctos), and wolves (Canis lupus). These survivors shared certain characteristics that gave them crucial advantages in the changing environment.

The secret to their success lay in their dietary flexibility and physical adaptations. Species that survived the end of the ice age had probably selected plant communities that would thrive in the post-Pleistocene climate throughout the ice age. It is interesting to note that caribou and muskoxen not only had a diet that favored the changing environment, but they had low foot loadings, which also favored the new environment.

The saiga antelope is an ice age survivor that once lived alongside woolly mammoths on the northern grasslands. Saigas historically lived from Hungary to northeast China, grazing across the vast Eurasian steppe, but today these unusual antelopes are confined mainly to Kazakhstan. Their distinctive bulbous nose helped them filter cold air and survive temperature extremes.

The Climate Pressure Cooker

Understanding how climate change drove evolutionary adaptations requires looking at the specific environmental pressures animals faced. Between 15,000 BP and 10,000 BP, significant warming occurred with global mean annual temperatures increasing by several degrees Celsius. This was generally thought to be the cause of the extinctions.

The temperature shifts weren’t gradual. Short-term (101–103 y) ecological instability was a characteristic feature of the mammoth steppe in arctic Alaska during the last ice age. Animals had to cope with rapid, unpredictable changes that could occur within decades rather than millennia.

According to this hypothesis, a temperature increase sufficient to melt the Wisconsin ice sheet could have placed enough thermal stress on cold-adapted mammals to cause them to die. Their heavy fur, which helps conserve body heat in the glacial cold, might have prevented the dumping of excess heat, causing the mammals to die of heat exhaustion.

The mammoth steppe itself represented a unique ecosystem that has no modern equivalent. The mammoth steppe may have been an azonal biome that never fully equilibrated to any single climate state. If true, this implies that, in addition to being a spatial mosaic of ecosystems, the mammoth steppe was also a temporal mosaic with soils, vegetation, and fauna that were chronically engaged in ecological successions triggered by repeated, short-lived, and radical shifts in climate.

Evolutionary Cold War Adaptations

The animals that mastered ice age survival developed remarkable evolutionary innovations. Some, like the woolly mammoth and musk ox, developed thick insulating coats, strong fat reserves, and unique metabolisms that helped them survive deep freezes. These weren’t just minor adjustments but fundamental biological restructuring.

With their thick coat of hair, large fat reserves, and specially adapted ‘antifreeze’ blood they were very well adapted to the cold. The woolly mammoth became nature’s ultimate cold-weather machine, complete with biological antifreeze running through its veins.

Scientists found that many cold-weather species began evolving around 2.6 million years ago – when the Earth’s polar regions started to freeze permanently. This timeline reveals that ice age adaptations weren’t sudden responses but rather long-term evolutionary projects spanning millions of years.

The research finds two principal stages in the development of cold-adapted vertebrates. The initial, in the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene (‘Ice Age’) period (approximately 3 to 2 million years ago), witnessed the appearance of genera that would eventually yield tundra and boreal specialists. The second stage, focused on the Middle Pleistocene Transition – approximately 920,000 to 640,000 years ago – is when most of today’s cold-climate species really came into form.

The Great Plant Revolution

While animals grabbed the headlines, plants underwent their own dramatic transformation during the ice age. The end of the last ice age triggered the loss of key types of vegetation. For instance, the mammoth steppe – a vast, grassy biome widespread during the ice age – vanished during the Earth’s transition to the current warm phase.

The vegetation that the animals ate was dominated by forbs (flowering plants that typically occur along with grasses in tundra, meadow and steppe environments and are often rich in nutrients). This nutrient-rich dietary component meant better nutrition for the grazing animals than a diet rich in grasses and sedges – typical of modern steppe and tundra – would have provided.

This result helped solve the puzzle of what likely limited plant growth in Earth’s past: carbon dioxide. Since levels of carbon dioxide in the last ice age were half (or less) of today’s concentration, the authors conclude that this was likely the limiting factor, rather than drought. Plants weren’t just battling cold; they were literally starved for carbon.

In the Southwest, desert vegetation was restricted to elevations of less than 1,000 feet in Death Valley and at the mouth of the Colorado River. Extensive pinyon-juniper-oak woodlands covered elevations of 1,000-5,500 feet. Now, these regions are mostly desert. Spruce-fir, mixed-conifer, and subalpine forests covered areas similar to present-day pinyon-juniper woodlands. Entire forest types migrated thousands of feet upward in elevation.

Human Hunters or Climate Culprits?

The debate over what actually killed the ice age megafauna continues to rage among scientists. The timing and severity of the extinctions varied by region and are generally thought to have been driven by humans, climatic change, or a combination of both. Human impact on megafauna populations is thought to have been driven by hunting (“overkill”), as well as possibly environmental alteration.

Some researchers hold humans responsible for the Ice Age extinctions, considering them the first wave in a human-caused global extinction crisis that continues to this day. Other researchers blame climate change, while still others contend that no one factor explains it. The evidence points in multiple directions simultaneously.

Recent archaeological discoveries have added fuel to the human hunting hypothesis. In 2024 a paper was published in Science Advances that added additional support to the overkill hypothesis in North America when the skull of an 18 month old child, dated to 12,800 years ago, was analyzed for chemical signatures attributable to both maternal milk and solid food. Specific isotopes of carbon and nitrogen most closely matched those that would have been found in the mammoth genus and secondarily elk or bison.

In 2023, Lindsey, Dunn and several colleagues published a paper claiming that human-ignited fires helped trigger vegetation changes in southern California that ultimately wiped out saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, wild horses and other megafauna from the area prior to their extinction elsewhere. The paper stresses that California faces similar conditions today, with megafires, rapid warming and drought.

The New World Order of Small Animals

The ice age megafauna was more diverse in species and possibly contained 6× more individual animals than live in the region today. Megafaunal biomass during the last ice age may have been 30× greater than present. When the giants vanished, they left behind a fundamentally different world.

People always ask me, ‘Why was everything bigger in the Ice Age?’ But that’s not really the right way to look at it. The question is, ‘Why is everything smaller now?’ This perspective shift reveals how the ice age extinctions didn’t just remove species but restructured entire ecological hierarchies.

Small mammals and birds suddenly found themselves in a world with dramatically reduced competition and predation pressure. This ecological release allowed many smaller species to diversify and expand into niches previously occupied by their giant relatives. The age of megafauna gave way to the age of medium and small-sized animals.

Environmental change in vegetation led to their downfall. The retreat of the ice sheet caused the large ice sheet that blanketed North America and Europe kept the seasons dampened, but as it retreated, it caused sharply defined seasons of winter and summer. This caused the animals to move to new ecological zones and adapt. New plants and terrain caused by sharp seasons in summer and winter created a new balance in the ecosystem. If you could not adapt, you died off.

Ecosystem Reconstructions and Biomass Crashes

Scientists have pieced together a picture of ice age ecosystems that reveals their extraordinary productivity. Horse was the dominant species in terms of number of individuals. Lions, short-faced bears, wolves, and possibly grizzly bears comprised the predator/scavenger guild. These weren’t sparse, struggling communities but rather dense concentrations of large animals.

The mammoth steppe supported animal densities that seem almost impossible by today’s standards. It must have been covered with vegetation even during the coldest part of the most recent ice age (some 24,000 years ago) because it supported large populations of woolly mammoth, horses, bison and other mammals during a time of extensive Northern Hemisphere glaciation.

Ecologists studying the ancient ecosystem speculate under ice-age conditions, the grazing animals were part of a positive cycle in which their droppings fertilized the soil and enabled the forbs to flourish. At the end of the ice age, conditions changed dramatically, becoming warmer and wetter. These conditions no longer favoured the mammal-forb relationship, and other types of plant (such as woody shrubs and trees) began to dominate the landscape. This shift likely had serious consequences for the animals and may have contributed to the large number of extinctions that happened at the end of the ice age.

As the ice age ended, the moisture gradient shifted and eliminated habitats utilized by the dryland, grazing species (bison, horse, mammoth). The proximate cause for this change was regional paludification, the spread of organic soil horizons and peat. The very ground beneath their feet transformed from grassland to bog.

Lessons from the Deep Past

The ice age transformation of global fauna offers crucial insights for understanding how species respond to rapid climate change. The cold-adapted species are amongst the most vulnerable animals and plants to ongoing climate change. Therefore, an understanding of how species evolved in the past is essential to help us understand the risks faced by endangered species today.

The cold-adapted species are amongst the most vulnerable animals and plants to ongoing climate change. Therefore, an understanding of how species evolved in the past is essential to help us understand the risks faced by endangered species today. The same animals that survived the ice age by adapting to cold are now facing the opposite challenge of rapid warming.

New research led by Bournemouth University has suggested that human populations remained spread across Europe, even during the harshest conditions. The study also found that resilient animals such as wolves and bears followed a similar survival strategy by staying in habitats across Europe. Staying put and adapting locally proved more successful than mass migration for many species.

The ice age experience reveals that successful species share certain traits: dietary flexibility, behavioral adaptability, and the ability to exploit changing environments rather than simply endure them. The same creatures that adapted to survive Pleistocene cold are now among the most susceptible to rapid global warming. If the Ice Age was a crucible for the cold-adapted, then our current moment may be a crucible for their survival.

Conclusion

The ice age reshaped global fauna through a combination of massive extinctions, remarkable evolutionary adaptations, and fundamental ecosystem reorganizations that continue to influence life on Earth today. From the catastrophic loss of megafauna to the remarkable survival strategies of cold-adapted species, these ancient climate shifts demonstrate nature’s capacity for both destruction and renewal. The plants and animals that emerged from this crucible were fundamentally different from those that entered it, creating the biological foundation for our modern world. Understanding these transformations provides essential insights for conservation efforts as we face our own era of rapid climate change. What lessons from the deep past will prove most valuable for protecting today’s vulnerable species? Tell us what you think in the comments.