In the heart of Victorian England, beneath the chalk cliffs of Dorset and the muddy quarries of the English countryside, lay secrets that would shake the very foundations of religious certainty. When the first massive bones emerged from ancient rock, few could have predicted that these fossilized remains would ignite one of the most profound intellectual revolutions in human history. The discovery of dinosaurs didn’t just introduce the world to creatures of unimaginable size and power – it challenged everything Victorians believed about their place in God’s creation.

The Shocking Discovery That Started It All

Picture this: It’s 1824, and a country doctor named Gideon Mantell is examining some peculiar teeth found in a Sussex quarry. These weren’t ordinary teeth – they were massive, serrated, and unlike anything in the known animal kingdom. When Mantell realized these belonged to a gigantic plant-eating reptile he would later name Iguanodon, the world suddenly became a much stranger place.

The implications hit Victorian society like a thunderbolt. Here was undeniable proof that colossal creatures had once ruled the Earth – creatures that weren’t mentioned anywhere in the Bible. For a society that had long believed in the literal truth of Genesis, this discovery was nothing short of revolutionary. The comfort of believing in a 6,000-year-old Earth, carefully crafted by God in six days, began to crumble beneath the weight of fossilized evidence.

When the Bible Met the Bone Yard

Victorian Christians faced an uncomfortable truth: their sacred text made no mention of these prehistoric giants. The Bible spoke of God creating animals on the fifth and sixth days, but nowhere did it describe massive, extinct reptiles that had dominated the planet for millions of years. This wasn’t just a minor theological hiccup – it was a fundamental challenge to biblical authority.

Religious leaders scrambled to reconcile these findings with scripture. Some argued that dinosaurs were simply animals that didn’t make it onto Noah’s Ark, while others suggested they were evidence of multiple creation events. The most desperate explanations claimed that Satan had planted fossils to test human faith, a theory that even devout Victorians found hard to swallow.

The Age of the Earth Gets a Dramatic Makeover

Before dinosaurs entered the picture, most Victorians accepted Archbishop James Ussher’s calculation that the Earth was created in 4004 BC. This neat timeline fitted perfectly with biblical chronology and made the world feel manageable, comprehensible, and divinely ordered. Dinosaur fossils shattered this cozy worldview with the force of a meteor impact.

Geologists studying the rock layers containing dinosaur bones realized that these creatures had lived and died over vast periods of time. The Earth wasn’t thousands of years old – it was millions, perhaps billions of years old. This revelation didn’t just challenge religious doctrine; it fundamentally altered humanity’s perception of time itself, stretching the history of creation far beyond what the human mind could easily grasp.

The psychological impact was profound. Victorians had to confront the reality that their entire civilization, their recorded history, their religious traditions – everything they considered significant – represented merely a blink of an eye in Earth’s true timeline.

Divine Design Meets Evolutionary Chaos

Victorian society was deeply invested in the concept of divine design – the idea that God had created every creature with a specific purpose and place in the great chain of being. Dinosaurs threw this orderly vision into chaos. Why would a benevolent God create such fearsome predators? Why would He allow entire species to go extinct if His design was perfect?

The discovery of Tyrannosaurus rex, with its bone-crushing jaws and razor-sharp teeth, particularly troubled Victorian sensibilities. This wasn’t the gentle, harmonious world described in Eden – this was a realm of violence, predation, and death that had existed long before humans ever appeared. The natural world began to look less like a divine garden and more like a battlefield where survival, not divine providence, determined which creatures would thrive.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Extinction

Perhaps nothing challenged Victorian religious thought more than the concept of extinction itself. If God was perfect and His creation was perfect, how could entire species simply disappear? The idea that the Almighty might create creatures only to let them die out seemed to contradict the very nature of divine perfection.

Dinosaur fossils provided undeniable evidence that extinction was not just possible but inevitable. These weren’t isolated cases of species dying out due to human interference – these were massive, successful creatures that had dominated their environments for millions of years before vanishing completely. The implications were terrifying: if dinosaurs could go extinct, what did that mean for humanity’s own future?

Natural Selection Enters the Victorian Stage

When Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species” in 1859, dinosaurs had already been unsettling Victorian minds for decades. The existence of these extinct giants provided powerful evidence for Darwin’s theory of evolution through natural selection. Here were creatures that had clearly adapted to their environments, evolved over time, and ultimately failed to survive changing conditions.

The fossil record of dinosaurs showed clear evolutionary progressions – from small, nimble creatures to massive, specialized giants. This wasn’t random creation; it was adaptation in action. Victorians could trace the development of different dinosaur lineages, seeing how creatures had changed over millions of years in response to environmental pressures.

For many, this was the final blow to the idea of special creation. If dinosaurs had evolved, if they had developed and changed over vast periods of time, then perhaps humans had evolved too. The connection between humans and the natural world suddenly became uncomfortably close.

The Rise of Scientific Authority

Before dinosaurs, religious authorities had largely controlled explanations about the natural world. Priests and theologians were the go-to experts for understanding creation, life, and humanity’s place in the universe. The discovery of dinosaurs marked a dramatic shift in intellectual authority from pulpit to laboratory.

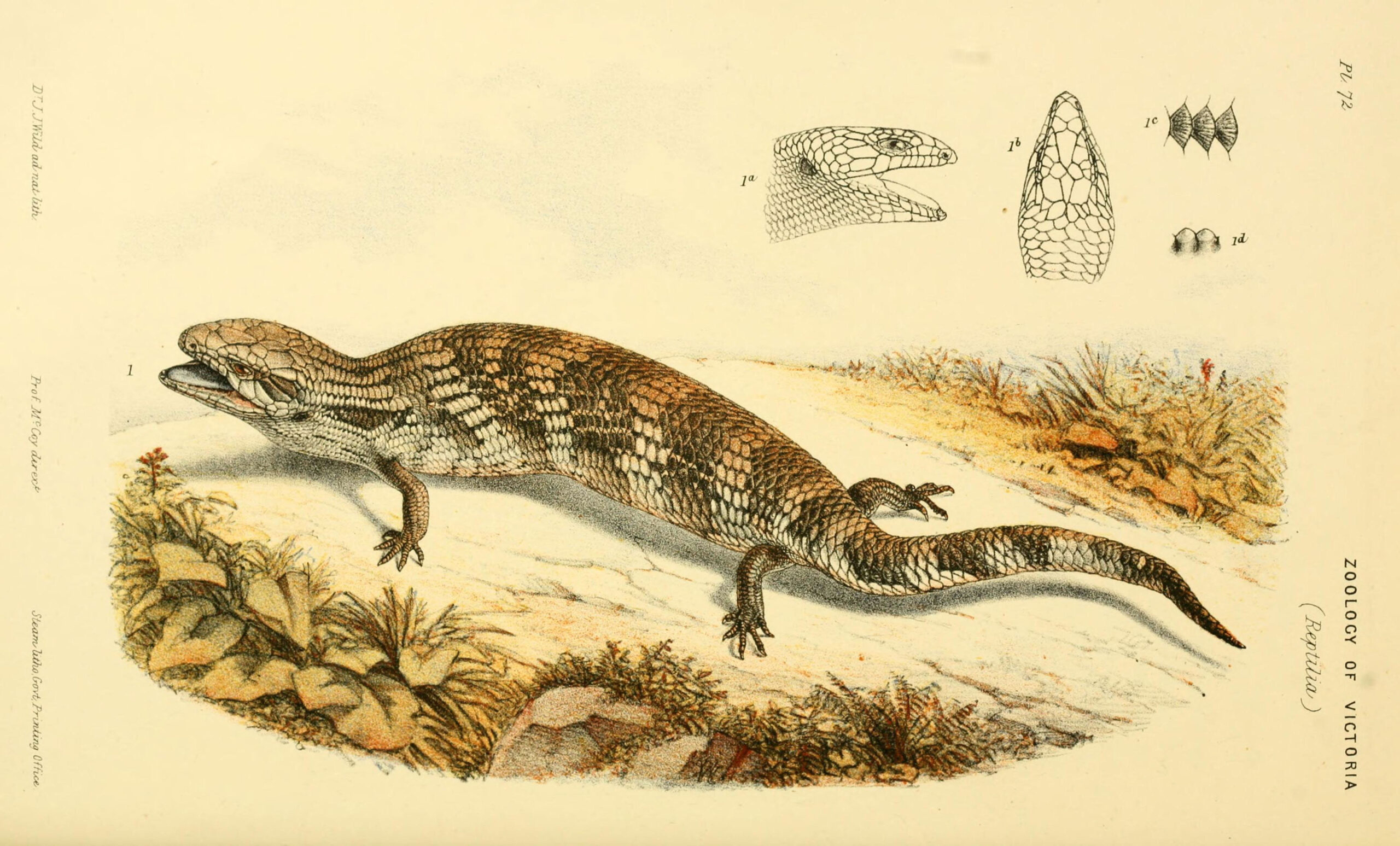

Paleontologists like Richard Owen, who coined the term “dinosaur,” became the new interpreters of natural history. Their scientific methods – careful observation, hypothesis testing, and evidence-based reasoning – proved far more effective at understanding these ancient creatures than theological speculation. The success of paleontology in reconstructing dinosaur life gave scientific methodology tremendous credibility.

Women, Fossils, and Breaking Social Barriers

The hunt for dinosaur fossils created unexpected opportunities for women to contribute to scientific knowledge. Mary Anning, working the fossil-rich beaches of Lyme Regis, became one of the most important paleontologists of her time. Her discoveries of complete ichthyosaur and plesiosaur skeletons challenged not just religious orthodoxy but social conventions about women’s intellectual capabilities.

Anning’s success demonstrated that scientific discovery didn’t require formal education or social status – it required careful observation, dedication, and courage to challenge established ideas. Her work showed that women could make fundamental contributions to understanding the natural world, a radical concept in Victorian society.

The democratizing effect of fossil hunting meant that important discoveries could come from anyone willing to search the rocks. This challenged the Victorian class system and suggested that truth about the natural world could be discovered by ordinary people, not just educated elites.

Public Imagination and Popular Culture

Dinosaurs captured the Victorian imagination in ways that no scientific discovery had before. These weren’t abstract concepts or invisible forces – they were tangible, dramatic creatures that people could visualize and understand. The Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures, unveiled in 1854, brought prehistoric life to the masses and sparked widespread fascination with ancient worlds.

Newspapers and magazines eagerly reported each new dinosaur discovery, and public lectures about prehistoric life drew enormous crowds. The appeal was irresistible: here were real dragons, creatures more fantastic than anything in fairy tales, yet supported by solid scientific evidence. This popularity helped spread evolutionary ideas far beyond academic circles.

The commercialization of dinosaur discoveries also marked a shift in how scientific knowledge was communicated. Museums competed to display the most impressive specimens, and fossil hunting became a popular hobby. Science was no longer confined to dusty laboratories – it was becoming entertainment, education, and adventure all rolled into one.

The Geological Revolution

Dinosaur fossils forced Victorians to completely reimagine Earth’s history. The rock layers containing these creatures told a story of gradual change over unimaginable periods of time. This wasn’t the catastrophic geology favored by those trying to reconcile science with biblical flood narratives – this was slow, steady change that required millions of years.

The principle of uniformitarianism – the idea that geological processes operating today had also operated in the past – gained tremendous support from dinosaur discoveries. The same processes that were slowly depositing sediments and fossilizing creatures today had been working for millions of years. This meant that natural laws, not divine intervention, had shaped the planet’s history.

Understanding deep time became crucial for understanding life itself. Dinosaurs had lived through multiple geological eras, adapting to changing climates and environments. This dynamic view of Earth’s history made the planet seem less stable and predictable than Victorians had imagined.

The Question of Human Uniqueness

Victorian society prided itself on human uniqueness – the belief that humans were fundamentally different from all other creatures because they possessed souls and had been specially created in God’s image. Dinosaurs complicated this comfortable assumption by demonstrating that intelligence, social behavior, and complex adaptations weren’t uniquely human traits.

Evidence emerged that some dinosaurs had lived in herds, cared for their young, and exhibited sophisticated behaviors. If these “mere animals” could display such complex social structures, what made humans truly special? The line between humans and the rest of creation began to blur in unsettling ways.

The discovery that dinosaurs had ruled the Earth for far longer than humans had even existed was particularly humbling. These creatures had achieved evolutionary success on a scale that dwarfed human achievements. Humanity’s brief time on Earth suddenly seemed less significant in the grand scheme of natural history.

Scientific Method Triumphs Over Dogma

The study of dinosaurs proved the power of scientific methodology over religious dogma in understanding the natural world. While theologians debated and speculated, paleontologists were reconstructing entire ecosystems from fossil evidence. They could determine what these creatures ate, how they moved, and even how they reproduced – all from careful analysis of bones and traces.

This empirical approach to understanding the past was revolutionary. Instead of relying on ancient texts or religious authorities, scientists were literally reading the history of life from the rocks themselves. The success of paleontology in revealing dinosaur biology and behavior demonstrated that observation and reason could unlock nature’s secrets more effectively than faith and tradition.

The rigorous methods developed for studying dinosaurs – comparative anatomy, stratigraphy, and careful documentation – became models for scientific research in other fields. The dinosaur revolution wasn’t just about understanding extinct creatures; it was about establishing science as the most reliable way to understand the natural world.

The Moral Implications of Prehistoric Violence

Victorian society struggled with the moral implications of discovering that violence and predation had dominated the natural world long before humans appeared. If God had created dinosaurs to hunt and kill each other, what did this say about the nature of divine morality? The discovery of dinosaur fossils with bite marks from other dinosaurs painted a picture of prehistoric life that was far from the peaceful Eden described in Genesis.

The concept of “nature red in tooth and claw” gained new meaning when applied to creatures with teeth the size of bananas and claws that could disembowel prey. This wasn’t the gentle, harmonious natural world that Victorian Christians wanted to believe in. It was a realm where survival depended on strength, cunning, and often brutal violence.

Some Victorian thinkers used dinosaur predation to argue that violence was natural and therefore morally acceptable. Others found the prehistoric world so disturbing that they rejected evolutionary explanations entirely. The moral implications of dinosaur discoveries continue to influence discussions about nature, ethics, and human behavior today.

Legacy of a Prehistoric Revolution

The discovery of dinosaurs fundamentally transformed Victorian understanding of nature, time, and humanity’s place in creation. These ancient creatures didn’t just challenge religious beliefs – they revolutionized how people thought about science, evidence, and the reliability of received wisdom. The Victorian encounter with dinosaurs established patterns of scientific discovery and public engagement that continue to shape our world today.

The courage shown by Victorian scientists in following evidence wherever it led, even when it contradicted cherished beliefs, set a powerful precedent for scientific integrity. Their willingness to revise fundamental assumptions about the world based on new evidence demonstrated the strength of the scientific method and the importance of intellectual honesty.

Modern debates about science and religion, evolution and creation, still echo the Victorian struggle to reconcile dinosaur discoveries with traditional beliefs. The questions raised by these prehistoric giants – about the age of the Earth, the nature of extinction, and humanity’s relationship with the natural world – remain relevant and provocative. Perhaps most importantly, dinosaurs taught the Victorians that the natural world was far stranger, more complex, and more wonderful than they had ever imagined.

What would you have thought if you had been among the first Victorians to gaze upon the reconstructed skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex?