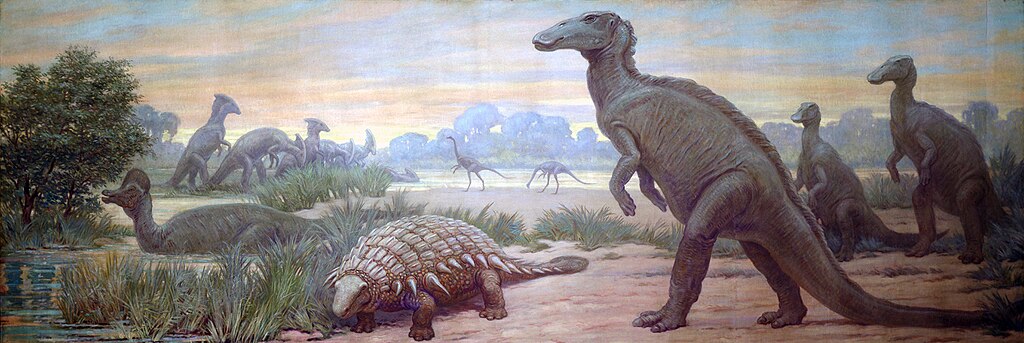

In the popular imagination, dinosaurs ruled the Earth alone for millions of years before mammals emerged after their extinction. However, paleontological evidence tells a far more fascinating story – one where our distant mammalian ancestors coexisted with dinosaurs for over 150 million years. This prolonged shared history represents one of the most intriguing chapters in vertebrate evolution. While dinosaurs dominated the landscape as the most conspicuous inhabitants, early mammals were quietly evolving in their shadows, developing adaptations that would later enable them to diversify into the countless forms we see today. Far from being a simple tale of dominance and submission, the relationship between these two groups reveals a complex ecological tapestry of adaptation, specialization, and evolutionary innovation that shaped life on our planet.

The Rise of Mammals During the Age of Dinosaurs

Mammals and dinosaurs both evolved from different groups of reptiles during the Triassic period, approximately 225 million years ago. While dinosaurs rapidly diversified and grew to dominate terrestrial ecosystems, early mammals remained relatively small and inconspicuous. These first mammals, including creatures like Morganucodon and Megazostrodon, were typically shrew-sized animals with specialized teeth for processing varied foods. Their emergence coincided with the early radiation of dinosaurs, establishing a relationship that would persist for over 150 million years. Throughout this vast timespan, mammals remained predominantly small-bodied, rarely exceeding the size of modern rabbits, likely due to ecological pressures from dinosaur dominance. Despite their diminutive stature, these early mammals were experimenting with diverse lifestyles and body forms that laid the groundwork for their later success.

Ecological Niches: How Mammals Found Their Place

Early mammals survived alongside dinosaurs by exploiting ecological niches that the larger reptiles couldn’t effectively utilize. Many early mammals were nocturnal, using the cover of darkness to avoid predatory dinosaurs that were likely more active during daylight hours. Their enhanced senses, particularly hearing and smell, made them well-adapted to nighttime foraging. Additionally, many early mammals were insectivores, consuming small invertebrates that were too minute to sustain the massive dinosaurs. Some species developed specialized diets, feeding on seeds, fruits, or even small vertebrates. The arboreal niche—living in trees—also provided a refuge for certain mammal groups, as smaller body size was advantageous for climbing and navigating branch networks. This pattern of ecological specialization allowed mammals to thrive in the margins of dinosaur-dominated ecosystems without directly competing with the much larger reptiles.

Evolutionary Innovations: The Mammalian Advantage

During their long coexistence with dinosaurs, mammals developed several crucial adaptations that would later prove advantageous. Perhaps most significantly, mammals evolved endothermy (warm-bloodedness), which allowed them to maintain high activity levels regardless of environmental temperatures. Their specialized dentition, with different teeth shaped for specific functions, enabled more efficient processing of diverse foods. Early mammals also developed a larger brain-to-body size ratio than their reptilian contemporaries, potentially allowing for more complex behaviors and problem-solving abilities. The evolution of mammary glands provided a reliable food source for offspring, while fur offered insulation that helped maintain body temperature. Particularly critical was the development of the middle ear bones from reptilian jaw bones, giving mammals extraordinarily acute hearing. These innovations, refined while living alongside dinosaurs, positioned mammals perfectly to diversify once dinosaurs disappeared.

Multituberculates: The Most Successful Mesozoic Mammals

Among the mammals that lived alongside dinosaurs, none were more successful than the multituberculates, a now-extinct group that first appeared in the Middle Jurassic and survived until the early Oligocene. These rodent-like mammals thrived for approximately 120 million years, making them the longest-lived group of mammals known to science. Multituberculates were named for their distinctive teeth with multiple cusps or “tubercles,” which were specialized for an omnivorous diet including seeds, fruits, insects, and possibly even small vertebrates. They developed body plans remarkably similar to modern rodents, demonstrating an early case of convergent evolution. Some multituberculate species evolved gliding abilities, similar to modern flying squirrels, allowing them to navigate the Mesozoic forests efficiently. Their extraordinary success during the Age of Dinosaurs demonstrates that mammals were not merely surviving in dinosaur-dominated ecosystems but actively diversifying and thriving in specialized niches.

Mammals as Prey: Living in Dinosaur Shadow

For many early mammals, life in a dinosaur-dominated world meant constantly avoiding becoming prey. Fossil evidence suggests that certain dinosaur species actively hunted mammals, as revealed by stomach contents and coprolites (fossilized feces) containing mammal remains. The small, nimble mammals likely relied on stealth, speed, and inaccessible hiding places to evade predation. Many species adopted burrowing lifestyles, constructing underground networks where larger dinosaurs couldn’t follow. The selective pressure of predation likely contributed to the evolution of acute senses and intelligence in early mammals. In some fossil sites, tiny mammal teeth have been found among dinosaur nesting grounds, suggesting they may have scavenged eggs or hatchlings when the opportunity arose. This predator-prey dynamic created an evolutionary arms race that shaped both groups over millions of years of coexistence.

The Geographic Distribution of Early Mammals

During the Mesozoic Era, early mammals achieved a global distribution alongside their dinosaur contemporaries. Fossil evidence reveals mammalian presence on all continents, including Antarctica, which was still connected to other southern landmasses in the supercontinent Gondwana. Different mammal groups showed distinct geographic patterns, with some families being restricted to certain regions while others achieved more cosmopolitan distributions. The movement of continents through plate tectonics significantly impacted mammalian evolution, creating barriers and bridges that alternately isolated or connected populations. Marsupial mammals, for instance, appear to have originated in North America before spreading to South America and eventually to Australia via Antarctica when these continents were still connected. This global presence demonstrates that despite their relatively inconspicuous nature, mammals were highly successful at adapting to diverse environments worldwide even while dinosaurs dominated the landscape.

Therians: The Ancestors of Modern Mammals

Among the diverse mammal groups living alongside dinosaurs, the therians—which include the ancestors of both marsupial and placental mammals—emerged during the Early Cretaceous period. These mammals possessed several anatomical advancements over earlier mammaliaforms, particularly in their reproductive strategies and skeletal structures. Unlike egg-laying monotremes, therians gave live birth to their young, representing a significant evolutionary development. Their dentition became increasingly specialized, with distinct molars, premolars, canines, and incisors that allowed for more efficient food processing. Therians also developed a more mobile shoulder girdle, enabling greater range of motion in their forelimbs. Cranial anatomy shows evidence of enhanced brain capacity, particularly in regions associated with sensory processing. These evolutionary innovations occurred while dinosaurs still dominated terrestrial ecosystems, showcasing how mammals were actively evolving significant adaptations long before dinosaurs disappeared from the scene.

Ecological Interactions Beyond Predation

The relationship between dinosaurs and mammals wasn’t limited to predator-prey dynamics; evidence suggests more complex ecological interactions existed between these groups. Some mammals likely scavenged from dinosaur carcasses, taking advantage of the abundant food source while avoiding direct competition. Certain mammal species may have lived commensally with dinosaurs, perhaps feeding on insects attracted to dinosaur dung or nesting materials. In some ecological contexts, mammals might have served as seed dispersers for plants that dinosaurs fed upon, creating indirect mutualistic relationships within the broader ecosystem. Some paleontologists have even suggested that small mammals might have performed parasite removal for certain dinosaur species, similar to modern relationships between crocodiles and birds. The complex web of interactions between dinosaurs, mammals, and other organisms created rich ecosystems with numerous interdependencies, challenging the simplistic view of dinosaurs as sole ecological dominants.

Mammals During the Late Cretaceous Diversification

The Late Cretaceous period, approximately 100-66 million years ago, witnessed a significant diversification among mammalian groups, even as dinosaurs continued their dominance. This era saw the emergence of metatherians (marsupial ancestors) and eutherians (placental mammal ancestors) as distinct lineages with their own evolutionary trajectories. Fossil evidence from formations like Hell Creek in North America reveals increasingly diverse mammalian communities existing alongside famous dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. Mammals of this period began exploring new dietary adaptations, with some species developing teeth suitable for omnivorous or even herbivorous diets. Body sizes also began to increase slightly in some lineages, though still remaining relatively small compared to most dinosaurs. Interestingly, this mammalian diversification coincided with changes in dinosaur communities, suggesting complex ecological relationships between the evolving groups. This late Mesozoic radiation set the stage for the explosive mammalian diversification that would follow the dinosaur extinction.

The Mystery of Repenomamus: Giant Among Early Mammals

While most Mesozoic mammals remained small, the remarkable discovery of Repenomamus giganticus from Early Cretaceous deposits in China shattered the stereotype of all dinosaur-era mammals being tiny, shrew-like creatures. This extraordinary mammal reached sizes comparable to a modern wolverine, weighing approximately 12-14 kilograms—enormous by Mesozoic mammal standards. Even more astonishing was the discovery of a Repenomamus fossil with the remains of a young dinosaur preserved in its stomach contents, providing direct evidence that some mammals actually preyed on dinosaurs. Repenomamus had powerful jaws and teeth suited for carnivory, suggesting it was an active predator rather than merely a scavenger. This exceptional mammal demonstrates that the ecological relationship between dinosaurs and mammals was more complex than traditionally portrayed, with some mammals occupying predatory niches alongside theropod dinosaurs. Repenomamus represents a tantalizing glimpse of mammalian ecological experimentation that occurred even while dinosaurs dominated terrestrial ecosystems.

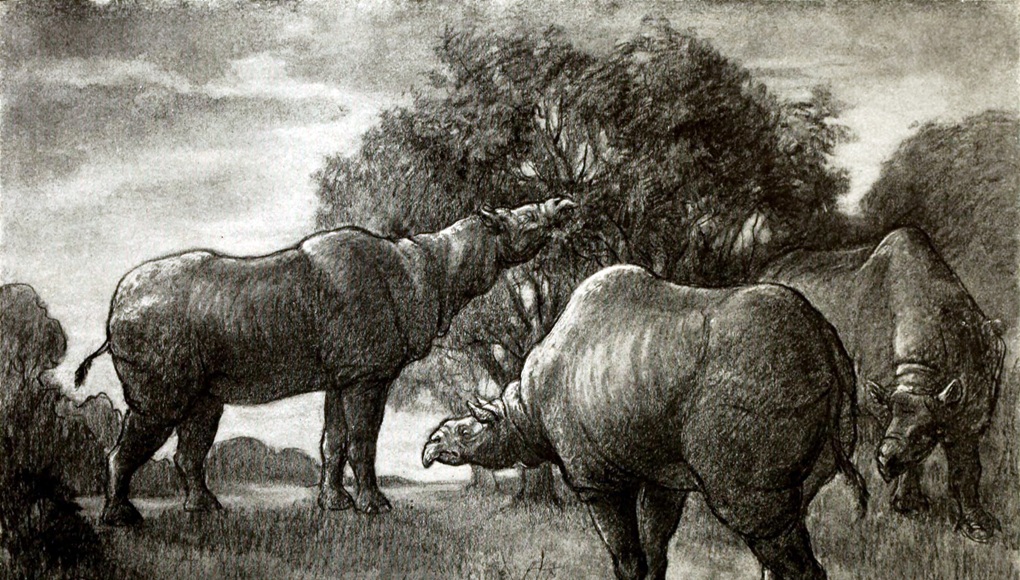

Mammalian Diversity Before the Asteroid Impact

By the end of the Cretaceous period, just before the asteroid impact that would end the Age of Dinosaurs, mammals had achieved remarkable diversity despite dinosaur dominance. Paleontological evidence reveals at least 28 distinct families of mammals living during the late Maastrichtian stage, representing a wide array of ecological adaptations. These included arboreal specialists with prehensile limbs, semi-aquatic forms with adaptations for swimming, specialized burrowers, and various dietary specialists from strict insectivores to omnivores and herbivores. The eutherian mammals (ancestors of placentals) had begun diversifying into primitive versions of some modern orders. Metatherians (marsupial ancestors) were particularly diverse in the southern continents. Mammalian dental complexity had reached new heights, with sophisticated chewing mechanisms evolving independently in several lineages. This pre-extinction diversity demonstrates that mammals weren’t simply waiting in the wings for dinosaurs to disappear—they were actively diversifying and exploring evolutionary possibilities throughout the Mesozoic Era.

The Transition: How the K-Pg Extinction Changed Everything

The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event approximately 66 million years ago radically transformed the relationship between dinosaurs and mammals. When a massive asteroid struck the Yucatán Peninsula, it triggered global catastrophes including widespread fires, acid rain, and a prolonged “impact winter” that blocked sunlight. While all non-avian dinosaurs perished in this cataclysm, certain mammal lineages survived, possibly due to adaptations like burrowing, nocturnal habits, and dietary flexibility that had evolved during their long coexistence with dinosaurs. The immediate aftermath saw a dramatic ecological restructuring, with mammals rapidly increasing in body size and diversity as they expanded into niches previously occupied by dinosaurs. Within just 300,000 years—an evolutionary eyeblink—mammals had produced species many times larger than their Cretaceous ancestors. Interestingly, the mammals that survived and thrived weren’t necessarily the most common pre-extinction species, suggesting that survival was determined by specific adaptations rather than previous ecological dominance. This pivotal transition ultimately set the stage for the Age of Mammals that continues today.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Coexistence

The 150+ million year shared history of dinosaurs and mammals represents one of evolution’s most fascinating chapters. Far from being a simple tale of dominance and submission, this relationship shaped both groups in profound ways. Early mammals developed the key adaptations that would later enable their spectacular diversification while navigating a world dominated by dinosaurs. Their relatively small size, acute senses, warm-bloodedness, and specialized dentition all evolved in response to the ecological pressures of the Mesozoic world. When non-avian dinosaurs finally disappeared, mammals were perfectly positioned to undergo an adaptive radiation into vacated niches. This long coexistence ultimately produced two extraordinary evolutionary success stories: the dinosaurs, whose avian descendants still thrive today with over 10,000 species, and the mammals, who diversified into everything from tiny shrews to massive whales. The shared history of these groups reminds us that evolution isn’t simply about competition, but about finding unique solutions to life’s challenges within complex ecological communities.